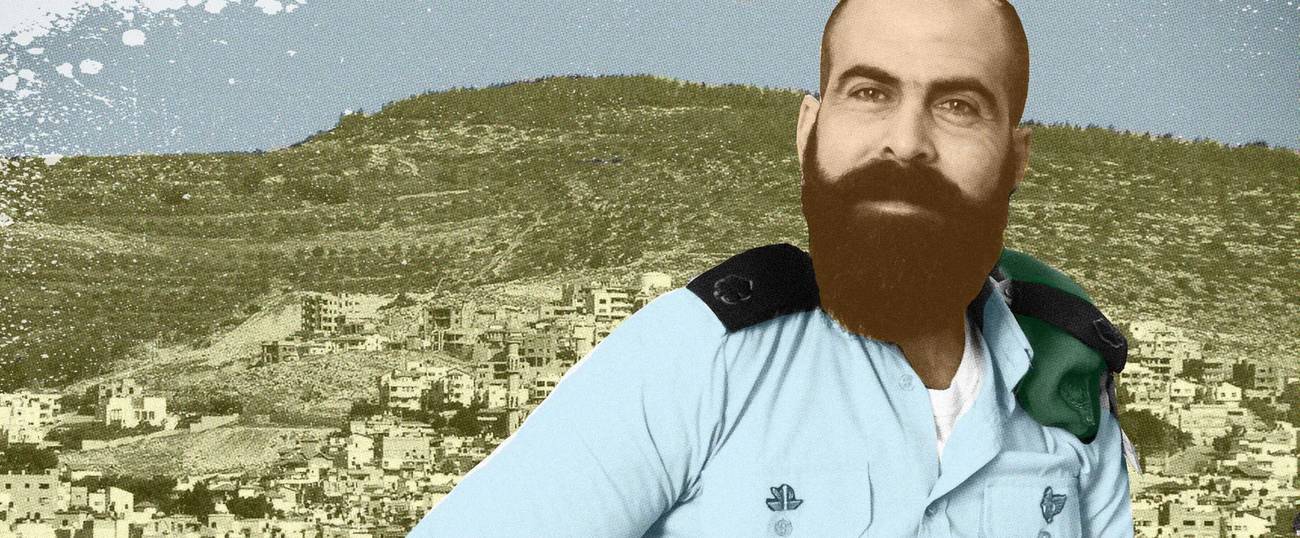

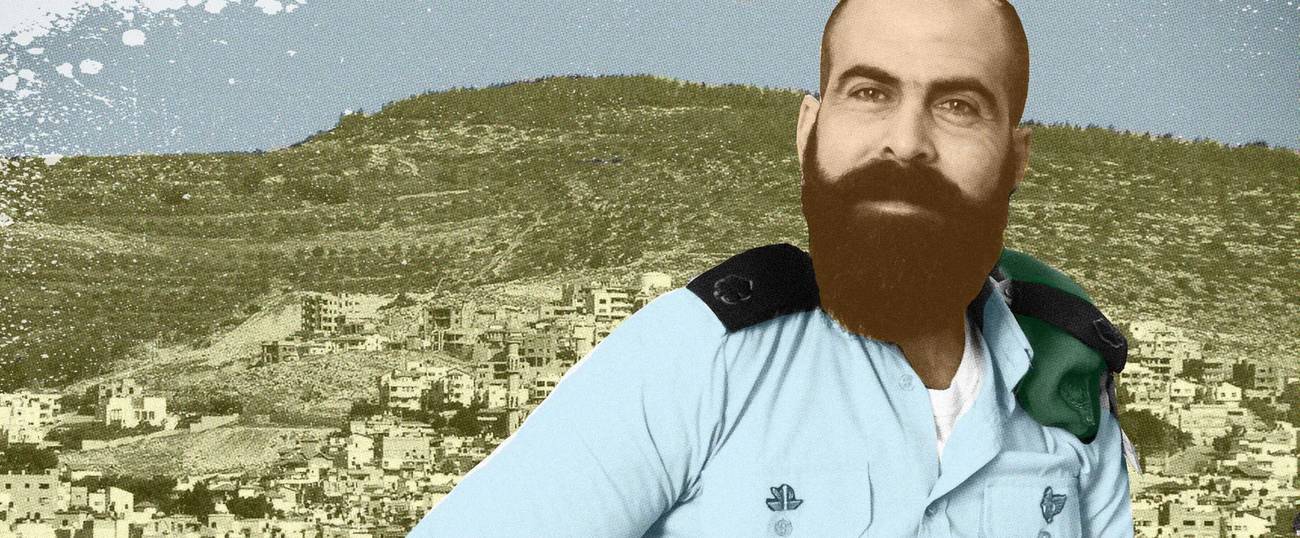

A Muslim Officer Fights for His Right to Defend the Jewish State

The case of IDF Major Alaa Waheeb

Major Alaa Waheeb is a tough career officer in the Israel Defense Forces who bears a striking resemblance to Theodor Herzl. In addition to his looks, he shares a dream in common with Zionism’s founder. “For as long as I can remember,” he told me, “I’ve always had this dream: to be like everyone else.”

Waheeb’s path to the IDF began at the age of 12, when a riot started in his hometown of Reineh in the Galilee. Angry youth threw Molotov cocktails on the road as wailing Border Police jeeps arrived on the scene. “I remember myself going out with the guys, clutching a stone,” he recalled. “I can see myself looking at it and asking: What are you doing? What are you going to destroy? Burn another bank? Another Dumpster? What good will that do? So I discarded the stone and went home, becoming the so-called chicken of my group.”

Waheeb—who until recently oversaw the Ground Operations’ vast training zone in the Negev Desert—will readily admit he is still considered an odd bird both within the Israeli army and in his Muslim-Arab community. But that preteen moment would shape his decision to forgo his given group identity and become an Israeli through service in the IDF. His unique family history sheds some light on Waheeb’s decision to join a military force that is still officially at war with his brethren across the border. His father, a Syrian from Aleppo, migrated with his family to Mandate Palestine in 1937 as a 4-year-old, settling in the religious Jewish community of Yavne’el on the southern shores of the Sea of Galilee.

Waheeb’s close relations with his Jewish neighbors would later prompt him to join the Border Police, an unusual move for an Israeli-Arab in the 1970s and 1980s. “He was considered a strange alien in his society,” his son said. Years passed, and Mr. Waheeb relocated with his father and two brothers to the Arab village of Reineh, where he took Alaa’s mother—a devout Muslim—as his second wife. Despite growing up among his mother’s conservative clan, Alaa was sent to a Christian school in nearby Nazareth, which he says shaped his liberal worldview. But as he neared the end of his studies and had to decide on the next move, the ideological differences between his parents came to the fore.

“My maternal uncle was completely opposed to my joining the army, because it contradicted all of his values. He had a great impact on my mother, whereas my father always supported me joining the draft,” Waheeb said. “The society I grew up in saw no importance in integrating in the state, especially through the army. We can work and travel freely in the country, but the military system was out of bounds, or so the thinking went.”

But Waheeb would not relinquish his dream of integration. Instead, he insisted on volunteering for the IDF (Arab-Israelis are exempt from the mandatory draft that applies to Jewish citizens). The shocked reception clerk at the recruitment office had him fill out forms and asked him to wait. The waiting period would last for no less than two years of uncertainty, during which the star student would work for Israeli arms manufacturer Rabintex and eventually enroll in Haifa’s Technion to study mechanical engineering.

“On March 20, 2000, I received a phone call notifying me I’m to be drafted in two days,” he remembered. “I had no idea how to prepare, with no older brothers who went through the process. I threw all kinds of things into a backpack, with no idea what to take or how long I’ll be gone for.”

On base, Waheeb immediately faced his first challenge: speaking Hebrew. He had learned the language as a subject in school but rarely had the opportunity to converse with native speakers. Then came the issue of his placement. The natural unit for Waheeb, his commanders believed, was the Bedouin Reconnaissance Battalion. “Where else would they place a Muslim-Arab?” he asks ironically. When he refused, he was offered a posting with the Border Police, a unit containing a high percentage of Arabic-speaking Druze.

Waheeb would have opted for the Golani infantry brigade, the best-known IDF unit among his Arab peers. But a family friend warned him of widespread racism in the popular combat unit. Eventually he was placed in Nahal, an infantry brigade famous for its Ashkenazi kibbutz volunteers and religious yeshiva students. Adamant on proving himself as an outstanding soldier, Waheeb volunteered to try out the brigade’s special-forces unit. He excelled in the arduous physical testing but was removed from the unit two weeks later.

“I cried endlessly,” he recalled. “No one wanted to tell me why I was transferred. Everyone knew that I was best at everything. I pressured my commander to give me an explanation for an entire month, and finally he broke and told me it was because I lacked the required security clearance.”

The timing of Waheeb’s recruitment would also prove unfortunate. Six months after joining the IDF, the Second Intifada erupted, quickly engulfing Arab cities and villages within Israel. Over the course of October 2000, 13 Israeli-Arab stone-throwers would be shot dead by Israeli police. When Waheeb would return home in uniform on weekends from basic training, he would wait at a bus stop outside his town until nightfall, then walk home. “Everything was boiling,” he said. “It was very difficult for people to see me as a soldier, so I shied away from friction, but I never hid my identity.”

***

The issue of volunteering in state institutions, such as the army or the Authority for National-Civic Service, continues to divide Israeli-Arab society. Balad Member of Knesset Hanin Zoabi has responded to the growing numbers of Arab civil service volunteers by dubbing them traitors. Her colleague, MK Jamal Zahalka, confronted a government initiative to encourage Arab volunteerism with a warning that integrating youth will be shunned and unable to find marriage partners. Service in the IDF is more controversial still. Some 1,000 Muslim Arabs (mostly from the Bedouin community of the Negev) now serve in the IDF as volunteers, while Gabriel Naddaf, a Greek-Orthodox priest, strives to expand army volunteer numbers within the Arab-Christian community.

Yet Waheeb believes that attempts to draw distinctions between Christian and Muslim Arabs based on their loyalty to the State of Israel are doomed to fail. “Arabs don’t want to be divided by religion,” he opined. “Christians are still largely nationalist Arabs.” Waheeb, who is not Bedouin, has managed to persuade two of his cousins to join the army, swaying even his antagonistic and nationalistic uncle. “Today, when he sees me with the rank of major, he couldn’t be more proud.”

Despite having received numerous military awards, Waheeb’s professional career has advanced more slowly than others. He still holds, though, that every Arab citizen of Israel should serve in the IDF. That is the message he brought to London, where he recently spoke to local students as a guest of the Zionist Federation UK during “Israeli Apartheid week.”

“I believe that those who refuse to recognize Israel’s existence and call this land ‘Palestine’ are hypocritical,” he said. “I can understand the Druze of the Golan who reject Israeli citizenship and insist they are Syrian, but these people carry Israeli IDs and enjoy state benefits. They effectively recognize the Israeli regime. I can’t wrap my head around it.”

Sitting in the vacant office of the Israeli ambassador to London last February, Waheeb reminisced about the cool reception he received from the yeshiva students who served in the infantry unit in which he was placed. “There were guys who didn’t want to speak to me,” he recalls. “They said, ‘We understand he’s Arab, and we don’t have any problem with him, but what is he doing here? This isn’t his place.’”

Hearing those words, Waheeb would always swallow his pride and smile. “The challenge is not to break down but rather impose your love on such people,” he said. “It’s easy to love someone who loves me; but greatness is to love someone who doesn’t. That’s true love.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elhanan Miller (@ElhananMiller) is a Jerusalem-based reporter specializing in the Arab world.