Anti-Russia

Liberty and servitude in the new philo-czarist age

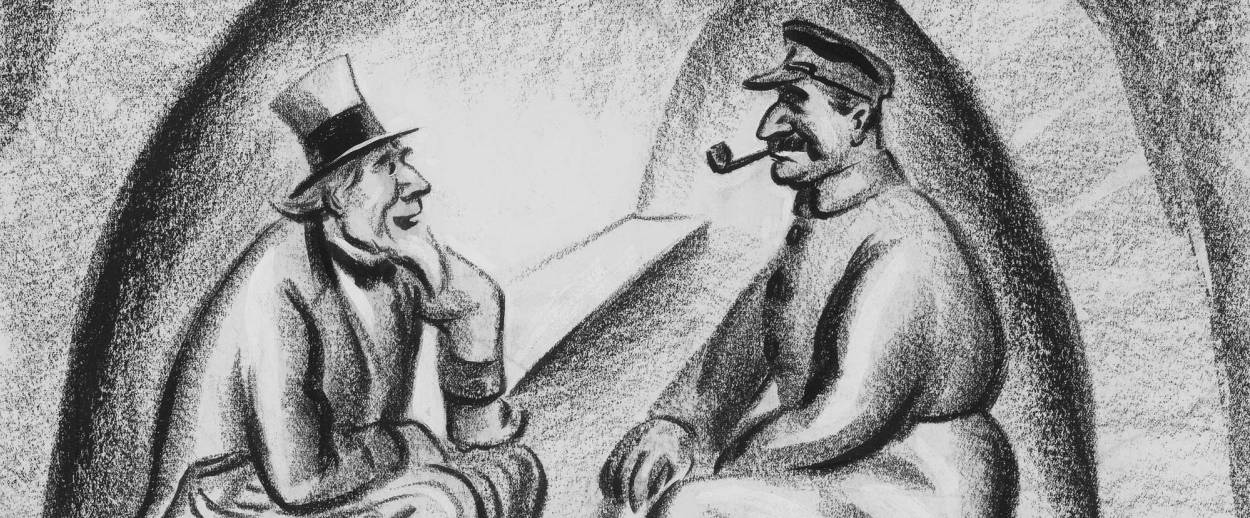

Hostility to Russia is the oldest continuous foreign-policy tradition in the United States, and that is because, apart from the ordinary conflicts of interest that might be expected to arise between two very large nations, a philosophical conflict has pitted America against the Russians, and has done so throughout the centuries, with the fate of the world at stake. Tocqueville identified the phenomenon on the last page of Democracy in America, Vol. I, from 1835. America, he explains, conquers with the plowshare of the laborer; Russia conquers with the sword of the soldier. America relies on personal interest and allows the individual to act on the basis of his own strength and reason. Russia concentrates the entire power of society in a single man. One country relies on liberty as its principal means of action. The other relies on servitude.

In our own era, we sometimes imagine America’s conflict with Russia was a phenomenon of the Cold War. It has been eternal, though. It is the struggle of democracy versus czarism, even if for a few years czarism called itself Communism.

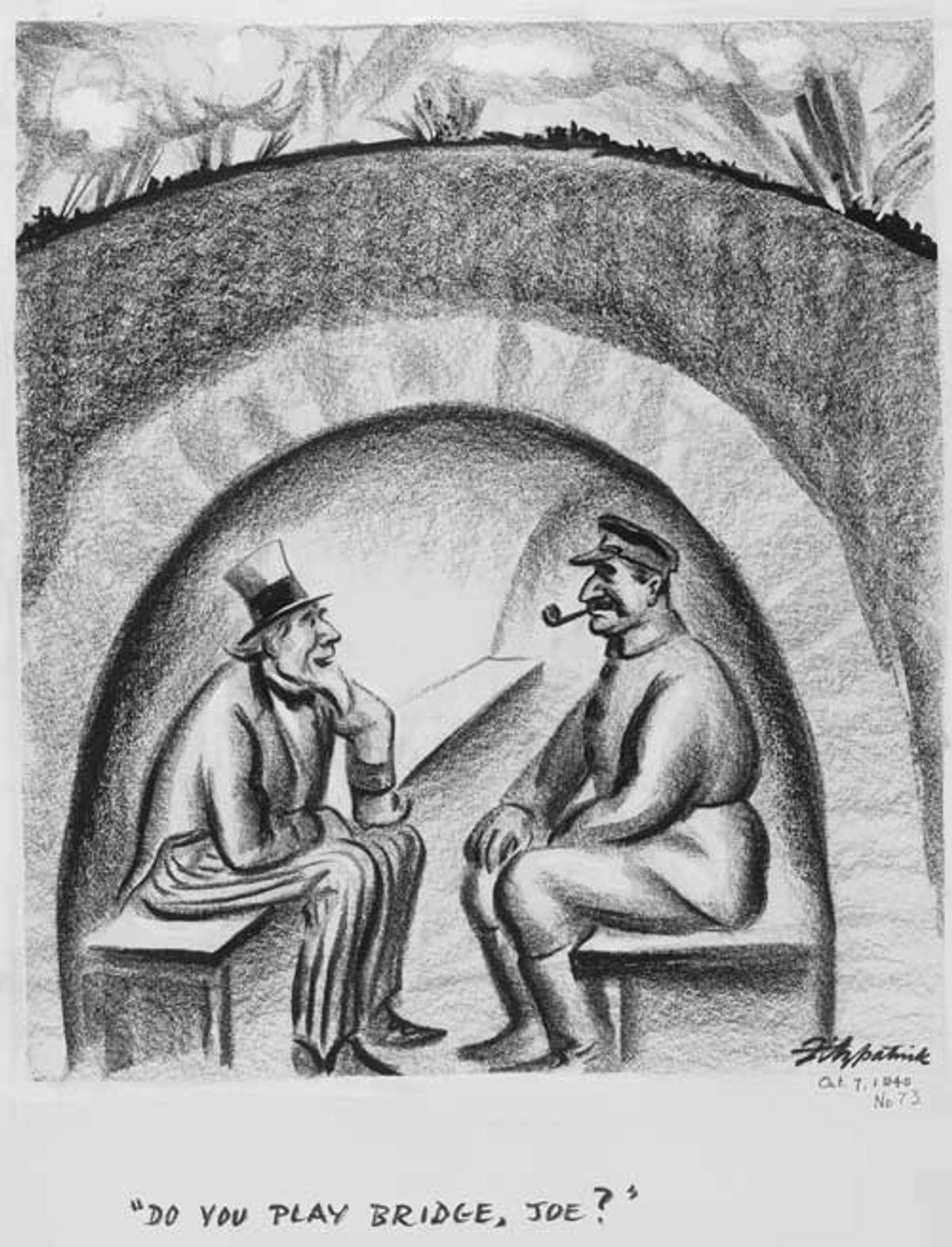

No one can mistake the fact that, over the centuries, America has more often than not struck up dismal alliances with dictatorships of every kind around the world, in the name of short-term benefits and strategic necessities. Franklin D. Roosevelt even struck up an alliance with Russia itself for a moment, out of an obvious military calculation. But behind the opportunistic alliances has always lurked the larger conflict with Russia, the eternal conflict—the conflict of two philosophies, liberal and tyrannical. The collapse of Communism and the end of the Cold War, beginning in 1989, were thrilling events, from the standpoint of liberal America, not just because it was thrilling to watch the Communist tyrannies collapse but because, without the challenge from the Soviet Union, America was at last liberated to give up the habit of allying opportunistically with various tyrannies. America was free to come out in favor of liberal movements everywhere in the world. Or so it seemed, for a few years. And, even afterward, when the naïveté of those first post-Cold War moments began to be obvious—even then, when still another kind of czarism began to revive in Russia, and tyrannical regimes and terrorist armies in other parts of the world proved to be stronger than imagined—even then, we Americans could feel confident that our ancient liberal mission was still intact, and it was still our duty and our honor and our destiny to stand up for the liberals of the world, and to face down their enemies, as best we could, which meant Russia, above all.

That is why the current decision of the Republican Party, at its highest pinnacle, to come out in favor of Vladimir Putin seems so shocking. The whole of American history would seem to say that such an about-face is impossible. It is happening, though. The break with American political tradition could not be sharper. President Barack Obama likes to say that Ronald Reagan must be rolling in his grave, which doubtless is true. But Tocqueville likewise is rolling in his grave, which is far more fundamental. It is a turning point in American civilization. No one is going to stop it, either. Sen. John McCain was just now in Kiev urging the Ukrainian soldiers to fight to the death against their Russian enemies, but McCain spent more of the last year than not tepidly endorsing the only major-party presidential candidate in American history who has supported the Russian enemies. If not even John McCain can be counted on to show any consistency in opposing the philo-czarist turn in American politics, who can be counted on? It is not going to be Chuck Schumer. A turning point, then. A surprise surrender. An unpredicted new page in Democracy in America.

***

To read more of Paul Berman’s political and cultural criticism for Tablet, subscribe to our print magazine.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.