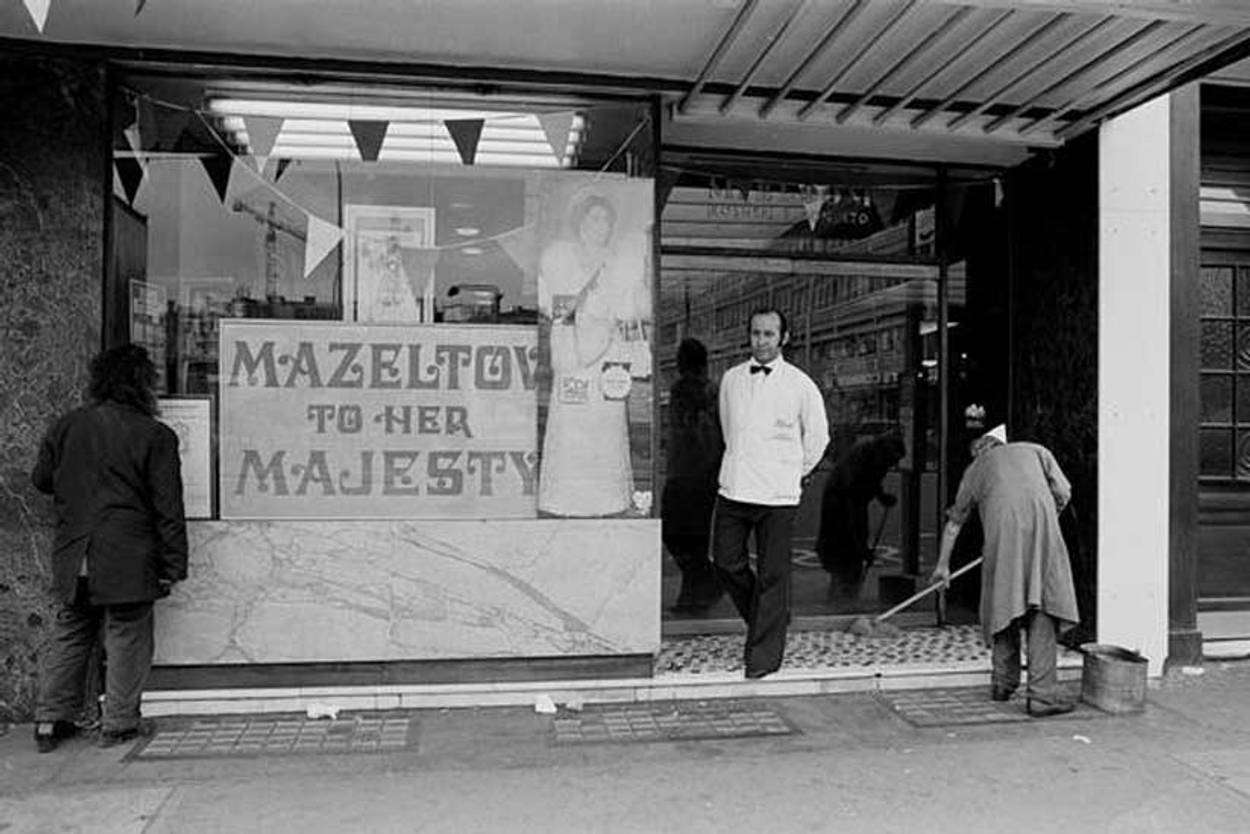

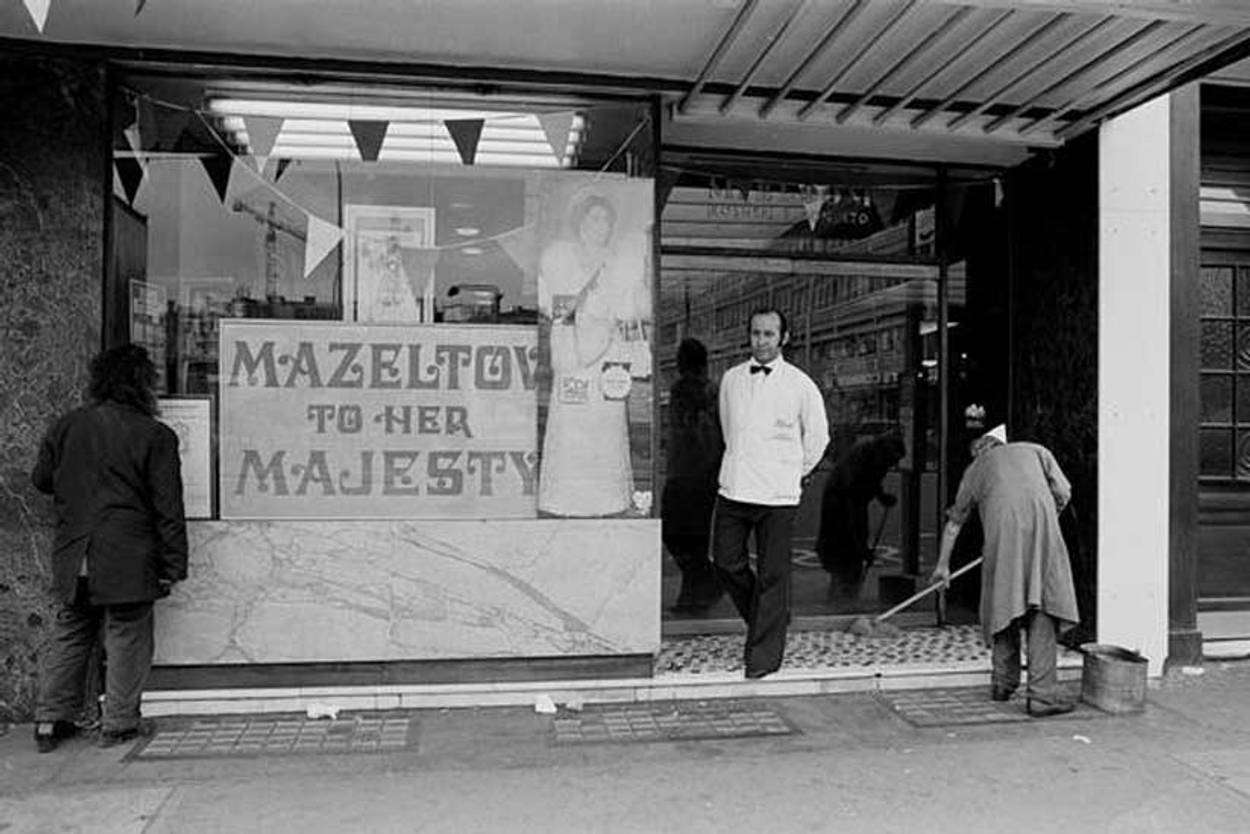

Art Thou Contented, Jew?

The British novelist on England, the Jews, and anti-Semitism today

Britain has a long and ignoble tradition of literary anti-Semitism, featuring such anti-heroes as Shylock, Fagin, and Svengali. When I first studied The Merchant of Venice in class, at the age of 12, I took against the play strongly, largely on account of the treatment of Shylock. I don’t think I was vividly aware either of his Jewishness or of the nature of anti-Semitism, for at the time I didn’t knowingly know many or perhaps any Jews. I just thought he’d been treated badly. His daughter Jessica had been seduced and stolen, and he was cheated of his revenge by a lawyer’s trick. I remarked in class that Portia had pulled a rabbit out a hat, “and a very shabby one at that,” and was reprimanded for using unliterary language. I stick by that view.

Productions of Oliver, the musical based on Oliver Twist, still provoke outrage as the Fagin stereotype is wheeled out yet again, and each time it is revived there are the predictable complaints. Shylock fares better, for it is possible, indeed almost de rigueur, to play him as tragic and misunderstood. Peter O’Toole gave a magnificent Shylock at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1960, an interpretation greatly admired by Jewish critics and the Jewish theater-going public, for O’Toole in the role was both dignified and heroic. He triumphed over the lesser actors. In those days he still had a noble nose, which he later modified (in my view unwisely) in order to play Lawrence of Arabia for David Lean. He looked much better before he had it fixed. I watched his performance many times, for my first husband, Clive Swift, played his friend Tubal, and their scene together was memorable. Tubal tells Shylock that his missing daughter Jessica has bartered her father’s ring for a monkey, at which Shylock cries out, “Thou torturest me, Tubal: it was my turquoise; I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor: I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys!” Who could not be on Shylock’s side? He has all the best lines.

O’Toole, of course, wasn’t Jewish, but my husband was. I saw this production with my parents just after Clive and I got married, and they were very impressed. This was just as well, as they had been somewhat apprehensive about our engagement, not because Clive was Jewish, but because we were both very young, and moreover he was an actor. This, I thought, was reasonable on their part. Acting is not the most reliable of professions.

Nobody in my family showed any sign of anti-Semitism, nor had I encountered it at school or at university. One or two of the more Orthodox of Clive’s family (notably his terrifying grandmother) were more hostile to me as a prospective in-law than anyone in my family was to him. Luckily this disapproval was kept from me, and to me, Jewishness wasn’t an issue. The two sets of parents got on well, pleasantly exchanging gifts at Christmas over the years, and I loved all the Swifts (apart from Grandma G.). One year my father made the mistake of sending a gift of smoked eel from the local fishmonger, as a change from the traditional smoked salmon, but nobody held it against him. But I was surprised when, at the time of my marriage, my father told me that he thought he ought not to accept an invitation to join the golf club because it had a Jewish quota, and it wouldn’t seem proper for him to appear to condone prejudice now he had acquired a Jewish son-in-law.

I didn’t know what a Jewish quota was, and he had to explain. My father was then County Count Judge of Northumberland, and apparently belonging to the golf club went with the job. He never played golf, so it was no loss to him, but it was an eye-opener to me. I had entered a new territory. I had never come across this sort of prejudice and wondered for a moment whether I had unwittingly embarked on a life of heroic struggle.

Jewish quotas are illegal in Britain now, and have been for a long time. But in those days, in the 1960s, they operated in several clubs and institutions, and I am sure some would tell you that, covertly, they still do. I wouldn’t know about that, as no one I know would want to join any of these discriminatory outfits, though some of my friends belong to the Garrick Club, which still doesn’t accept women members.

Having half-Jewish children and wholly Jewish in-laws has sensitized me to anti-Semitic attitudes and press coverage. I know that to the Orthodox my children don’t qualify as Jewish, because they are Jewish only through the paternal line, but they are half-Jewish to me and to themselves. Some of my Jewish in-laws and Jewish friends are more Jewish than others: Some do Friday nights, some won’t drink German wine or go to Germany, some won’t eat shellfish. Some make their own gefilte fish, others detest it. Some read Holocaust literature and fiction obsessively, others avoid it. (It was a Jewish friend who introduced me to the work of Primo Levi in the 1960s, long before he was well known outside Italy.) Some call one another (usually in the friendliest way, sometimes more acrimoniously) “Jew-hating Jews.” Some sing sacred music in Christian choirs, some prefer Fiddler on the Roof. Some go to synagogue, some haven’t been near one since their own bar mitzvah. But all of them, all of them think of themselves as English.

I don’t remember when I first became conscious of the Jews. As I was born in 1939, I was brought up in an England traumatized by war, and when I was a teenager I was aware that European Jews had been the victims of genocide, although we were not encouraged to look at Holocaust pornography. My father, as a young left-wing lawyer, had been involved with the placement of Jewish refugees in Sheffield in the 1930s, but I didn’t know that until much later. I don’t think I connected contemporary Jews with the Jews of the Bible, who seemed as remote from me as the Roundheads and Cavaliers, or the Ancient Britons who built Stonehenge. We read the Bible, but nobody at home or at school or during my university career ever suggested that the Jews were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus. If I thought anything, I thought it was all the fault of Pontius Pilate, and Pontius Pilate was a Roman. The Romans, I knew, went in for crucifixions. The notion of the collective guilt of the Jews would have appeared ludicrous to my Shavian mother and Quaker father, and ludicrous in the Nonconformist Protestant North of England where I was brought up. I have since discovered that some English and Irish children, educated in convents or Catholic schools, did have some anti-Jewish indoctrination, but this would have been utterly unacceptable in the world in which I was reared. I was spared any of that nonsense and only came across it, with some disbelief, in recent years.

We did, of course, study the Bible at school, though, as it was a Quaker school, we studied it less assiduously than most schoolchildren, for the Quakers are not very scripture-dependent. But we did learn a few verses every morning, most of them from the New Testament or the Psalms, but sometimes from Isaiah or Ezekiel or, if we were lucky, from the Book of Job. We loved the Book of Job—its gloominess, its poetry, its majesty. The passage about the horse particularly delighted us, although I now see that the horse is a warhorse, and therefore should have been forbidden us, as we were meant to be pacifists. “He paweth in the valley and rejoiceth in his strength … and oft as the trumpet soundeth, he saith, Aha!” Magnificent, but not very Quakerly.

Did we think of Job as Jewish? Not really. But we liked the Old Testament stories—Adam and Eve, Jonah and the Whale, Naomi and Ruth, Samson and Delilah, Joseph and his brothers. English literature is permeated by the prose and poetry of the King James Bible. The phrases linger on in the memory, and one of my most treasured possessions is a Biblical Concordance, which I keep by the bed. I know one can easily find quotations on the Internet now, but they seem more valuable when tracked down in a leather-bound gilt-leaf volume. The other night I dreamed about my younger son Joseph. “Behold, this dreamer cometh!” were the words to which I woke, and which I found at once in my Cruden’s Concordance. And I remember writing a poem at school about Joseph, of which I can remember only the last line, which went “this pit in Dothan, where no water is.” Maybe it was a dramatic monologue in iambic pentameter, in Joseph’s voice, or maybe it was a cry of adolescent misery. I was rather proud of it.

My Grandfather Drabble was called Joseph. He was a Yorkshire Methodist. The choice of name seemed to unite the families. All three of my children have Biblical names.

The debate about Jewish descent fascinates me, and it breaks out from time to time in England in a public storm, most recently about ethnic or religious criteria for pupils and teachers at a celebrated North London school, the Jewish Free School, or the JFS as it is always known. A lot of people want to send their children to the JFS, not because it is free (although, being a state school, it is) but because it is rated “outstanding,” and competition for good state schools is fierce. According to the National Secular Society (which opposes all Faith Schools), the controversial 2009 exclusion case “turned on whether the child in question was Jewish. It is generally recognised that a person is Jewish if his or her mother is Jewish. The mother in this case (who actually taught at the school) had converted to Judaism and regarded herself as Jewish. But her conversion had not been recognised by the Office of the Chief Rabbi and therefore also was not recognised by the school.”

A good deal of room for acrimonious debate and expensive litigation there, and at the U.K. Supreme Court in December 2009 it was ruled that the JFS admissions policy amounted to direct discrimination on the basis of race. That probably won’t be the end of the story.

My sons went to a North London state school (not the JFS), which because of its catchment area had a fairly large Jewish intake, with many children from academic and professional families. I remember one alumnus saying of this school, “No matter how clever you were, there was also some Jewish kid who was a lot cleverer than you, and he was always top of the class.” I don’t know if that’s an anti-Semitic remark or not.

The JFS understandably didn’t like being accused of racial discrimination. Jews have been discriminated against in British society for centuries and don’t like a counter-accusation. What constitutes anti-Semitism in Britain today is another matter. It’s not to do with golf clubs or dining clubs, for Race Discrimination Acts and Equality Acts have largely brought an end to that. It shouldn’t feature in educational establishments and on the whole doesn’t: The mirror-image JFS case became notorious precisely because it was exceptional. My instinct is to claim that it has diminished almost out of normal daily existence, although that may be wishful thinking on my part, or ignorance, or proof of a sheltered life. Accusations of anti-Semitism still abound, and the tabloid press loves to make the most of stories of swastikas on defaced synagogues—arguably, inflammatory coverage that is in itself a form of anti-Semitism. The tabloid press is not a trustworthy source of information. But the truth is that these episodes are rare.

There were several acts of vandalism after the conflict in Gaza in 2008, as there were in the United States and Canada. When we talk about anti-Semitism, do we really mean anti-Zionism? They are not the same, although some argue that they are. British academics who boycott conferences in Israeli universities may be anti-Zionist, but they are not necessarily anti-Semitic, although the two charges are often conflated. Most of them would deny hotly (and rightly) any tinge of anti-Semitism and insist that they are protesting against Israeli policy towards the Palestinians. Neither a nation nor a race should be identified with its foreign policy. A few years ago I protested vehemently against the illegal detention of so-called “illegal combatants” in Guantanamo (in which our British government was lamentably and supinely complicit) and said, provocatively, that Guantanamo filled me with a deplorable and painful sense of anti-Americanism. I did not say that I hated America or Americans, although many think I did. Nor does an acute distress at the deadly invasions of Lebanon or Gaza imply that a critic of Israel hates Jews. To suggest that anti-Semitism is the underlying cause of British protests about Gaza is offensive and unjustified.

Both anti-Zionism and a support for the Palestinian cause are perhaps more prevalent and more boldly expressed in the United Kingdom than in the United States. In 2002, Cherie Blair, a human rights lawyer and Prime Minister Tony Blair’s wife, let slip some words of what was interpreted as sympathy for suicide bombers. Although she got some flak for this from British rabbis and the Israeli embassy, she was not violently attacked across the board for racism or indiscretion. I doubt if she’d have dared to express herself so spontaneously and unguardedly in America. She later apologized for any offense. What she actually said, at a charity event to raise funds for MAP (Medical Aid for Palestinians) was this: “As long as young people feel they have no hope but to blow themselves up we are never going to make progress.” This does not strike me as an expression of support for Hamas, but it is easy to see how it could be misrepresented.

It is perceived, in Britain, that the U.S. pro-Israel lobby attempts, successfully, to censor criticism of Israel. I don’t know how fair this suspicion is, but it exists, and it was inflamed by a minor incident in October 2006 when Australian-born, British-based writer Carmen Callil was in New York promoting her remarkable account of Vichy France, Bad Faith. This gripping, carefully researched yet very personal book tells the harrowing story of the betrayal and deportation of French Jews during the Occupation, and on publication it was highly praised in Britain, and also by French and Jewish critics who rightly read it as a fierce indictment of the Vichy regime and an important contribution to our historical knowledge of the period. The problem arose when it was noted that in the last chapter Callil suggests that in recent times the Israeli treatment of Palestinians echoes the wartime persecution of the Jews. This is not a novel proposal, and the theory that violence begets violence is widely if not universally accepted. Callil does not go as far as Nobel Prize-winner José Saramago, who compared the conditions in Palestinian refugee camps to those in a concentration camp, but nevertheless her criticism of Israel annoyed some American Jewish readers, and, alerted to potential unpleasantness, the French Embassy nervously canceled a party in her honor. This was pusillanimous of the French, and understandably annoyed Callil.

It would be disingenuous to suggest that her book could in any way be construed as anti-Semitic. It is not.

I don’t think this specific incident could have happened in England. Here, these days, we are more sensitive to complaints from Muslims and other religious or ethnic minorities than to complaints from pro-Israel or agnostic Jews. There have been acts of official and unofficial censorship—plays closed, books burned, writers driven into hiding—and some cowardly decisions on the part of our government. Both Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Labor leader Michael Foot stood staunchly by Salman Rushdie in 1989 when the Satanic Verses fatwa was delivered, but I sometimes fear that since the London bombings of 2005 we are condoning censorship more easily than we did, in the name of multiculturalism. But we do not censor the Jews, nor do they censor themselves. It is Sikh and Muslim protests that exercise our consciences now. British Jewish writers can be as outrageous as they choose without unduly upsetting their own or the wider community. They are at home here, and have been for a long time.

Howard Jacobson, a Manchester-born novelist sometimes described as our own Philip Roth, returns again and again to deeply black Jewish comedy and to the sensitivities and particularities of British Jews. His 2006 novel, Kalooki Nights, is a fascinating compendium of information about Jewish life and Jewish urban folklore in Britain in the last half century, in turn affectionate, brutal, emotional, satiric, and tragic. It demonstrates that there are at least as many forms of Jewishness in Britain today as there are of Englishness, or Scottishness, or Irishness—there are Marxist, northern, London suburban, Oxford academic, secular, Zionist, anti-Zionist, rich, poor, tolerant, insanely intolerant, observant, card-playing, fell-walking, strictly kosher, bacon-devouring, lockjaw-fearing Jews. (We all feared lockjaw too, in our white suburban Yorkshire school: I think this was a 1940s thing, not a Jewish thing.)

His protagonist Max Glickman, son of a hard-line left-wing secularist, is a cartoonist, forever reworking his masterpiece, Five Thousand Years of Bitterness, a brilliant narrative device that gives Jacobson license to explore Holocaust jokes in the worst possible taste, and to caricature both extreme Orthodoxy and polite and impolite social anti-Semitism. He says things that we non-Jews would never dare to say. Spitefully presented by his grotesque non-Jewish mother-in-law with a nodding toy rabbi to hang in the back of his provocative Volkswagen (or Völökswagen, as he chooses to spell it), he wonders if it comes from a souvenir shop in Jerusalem. “You can never tell with tat; bad taste narrows the gap between the sentimental way you see yourself, and the scorn with which others see you. Half of what’s for sale in Israel you’d consider anti-Semitic if you saw it anywhere else.”

Recently I was on the judging panel for a National Short Story Award organized by BBC Radio 4. One of the five winning tales (“Other People’s Gods,” by Naomi Alderman) was set in the very traditional North London Jewish neighborhood of Hendon. The protagonist, a family man called Bloom, purchases on a whim a statuette of Ganesh, the Indian elephant god, which seems to bring him and his family good luck. The rabbi expostulates, accusing him of worshipping an idol, and destroys Ganesh. The mild-mannered ophthalmologist, in revenge, wrecks the synagogue. It is a good-humored multicultural story with an excellent Biblical punch line, and was brilliantly read on air by that fine actress Miriam Margolyes. Inoffensive as this little fable was, I was slightly anxious (how anxious we are these days!) that some might find it objectionable, and was reassured to learn that it had been cleared for broadcast by the higher powers of the BBC. I doubt if a similarly light-hearted yet literally iconoclastic story set in an orthodox Muslim neighborhood would have been passed as easily.

By Jacobson’s standards, Alderman’s tale was mild. Yet it raised questions of compliance, the new editorial fear word at the BBC. Novelists and story writers need not comply, but employees of the BBC must.

The BBC declined to broadcast Hanif Kureishi’s story “Weddings and Beheadings,” a not-at-all light-hearted prize-winner entered three years earlier for the same award. This controversial decision was made as “a courtesy” to the family of Alan Johnston, the BBC reporter on the Middle East who was kidnapped by Palestinian militants and was being held hostage at that time, in very delicate diplomatic circumstances. (He was eventually released after four months in captivity.) Kureishi’s story had been written before this grim episode, and did not refer to it, though it is narrated by a fictitious film maker who makes his living from news videos of violent death.

I should make it clear that Kureishi’s outspoken work has never been subjected to censorship, although he has been at times provocatively anti-Islamic in his writing—his mockery of extremists reading messages in a Koran-inscribed sacred aubergine in The Black Album (1995) was greeted with much praise. The circumstances in which the BBC decided not to broadcast his story in 2006 were wholly exceptional, and the story was published along with the other prize-winners in due course. The BBC treads a difficult path. I wouldn’t like to be its director-general. The decision not to broadcast was widely discussed and in some quarters much criticized. I do not know whether it was right or wrong.

If, as I have stated, it is perceived in Britain that there is a powerful pro-Israel lobby in America, I know from American friends that our press and some of our celebrities are perceived as pro-Palestinian. Reporter Robert Fisk of the Independent is cited as a Palestinian apologist, as is Vanessa Redgrave. (I went with Vanessa and her brother Corin Redgrave on a delegation to Washington for the Guantanamo Human Rights Commission, and it was clear that while Vanessa attracted media coverage, she also attracted hostility.) Pro-Israel Americans believe that the BBC is biased against Israel, but here, many on the left (including readers of the New Statesman) believe that the BBC is pro-Israel, particularly after its much-publicized refusal to broadcast a charity appeal for the victims of the Gaza bombardment. Attacked from both sides, the BBC probably gets it right, and its veteran reporter on the Middle East, Jeremy Bowen, is reassuringly reliable, rising calmly above the waves of partisan extremism. The BBC remains an independent voice. The reporting on the recent planned expansion of 1,600 new homes in occupied East Jerusalem seemed to me impeccably neutral. The settlements are considered by many (including President Obama, Hillary Clinton, and me) to be unlawful, and I cannot see how anybody could accuse the BBC of anti-Semitic or anti-Israeli bias in its coverage.

But we know that a crude political and racial anti-Semitism flourishes in some British constituencies where Muslim radicals campaign. This is a thousand miles away from the golf club quota or the launch party ban, and much more inflammatory. Sheffield born Oona King, formerly Labor Member of Parliament for Bethnal Green and Bow in East London, is of mixed race—Jewish on her mother’s side, African-American on her father’s—and has been subjected to hate mail and abuse from several directions by her political opponents and her (largely Muslim) ex-constituents. She lost her seat in 2005 to the maverick pro-Palestinian George Galloway, having herself initially supported the invasion of Iraq. Galloway’s new Respect Party illustrates a strange new alliance of multicultural Britain, founded, Howard Jacobson would argue, on a profound ignorance of the history of Israel and of British involvement in the Middle East. Peter O’Toole’s nose and Lawrence of Arabia have a lot to answer for.

In sum, my own conclusion is that old-style anti-Semitism in Britain today has largely withered away, although as long as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains unresolved there will always be flash points abroad to trigger outbursts of hostility at home. But these do not in my view reflect a deep-rooted underlying establishment antagonism to the Jews in England. The golf club snobbery of the past has gone. Of course Jewish people here are sensitive to and worried about perceived slights and off-color jokes—what else would you expect, after centuries of Shylock and Fagin and Svengali? Britain remains, whatever people tell you, a class-obsessed society, but anti-Semitism no longer features high on the prejudice agenda. Howard Jacobson wouldn’t agree with me and would no doubt label me a representative of what he calls “cosy old lazy old easy-come easy-go England.” But there are worse things to be than that.

Margaret Drabble is the author of The Sea Lady, The Seven Sisters, The Peppered Moth, and The Needle’s Eye, among other novels. She is the editor of the fifth and sixth editions of The Oxford Companion to English Literature.