Promises to Keep

Jonathan Schneer’s history of the Balfour Declaration frames a still-unfolding struggle

In 1905 Najib Azoury, a Lebanese Christian intellectual and political activist, published a prophetic book, Le réveil de la nation arabe dans l’Asie turque (or, “The Awakening of the Arab Nation in Turkish Asia”). In it he argued that: “Two important phenomena, of the same nature but opposed, are emerging at this moment in Asiatic Turkey. They are the awakening of the Arab nation and the latent effort of the Jews to reconstitute on a very large scale the ancient kingdom of Israel. These two movements are destined to confront each other continuously, until one prevails over the other. The final outcome of this struggle, between two peoples that represent two contradictory principles, may shape the destiny of the whole world.”

As the subtitle (The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict) of his book implies, Jonathan Schneer sees the Balfour Declaration as a milestone on the path sketched by Azoury 12 years before it was issued. One of the major themes of the tale he tells is the inevitable clash produced by Great Britain’s simultaneous and often duplicitous cultivation of the two competing claims—from Zionism and Arab nationalism—on Palestine.

Two or three decades ago it was fashionable among professional historians to dismiss diplomatic history as the study of what one clerk wrote to another. One could indeed point to too many middling diplomatic historians who filled volumes with long quotes from diplomatic dispatches and the minutes written in their margins in foreign offices. But a series of first-rate, sometimes spectacular, studies demonstrated that diplomatic history could be written in a grand way. Several of them focused on World War I and its sequels in the Middle East.

Thus Elie Kedourie at the London School of Economics devoted his talents and efforts to deciphering Britain’s role in the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and the construction of the contemporary state system in the Middle East. David Fromkin described in fascinating detail in his history, The Peace to End All Peace, how in the aftermath of World War I, the victors fashioned the modern Middle East. With a perceptive eye and the talent of the raconteur, Fromkin combined intriguing portraits of the main actors, a fine analysis of the issues and forces at work, and a trove of entertaining anecdotes. Margaret MacMillan, the Canadian historian (now an Oxford don) and a scion of Lloyd George’s family, used a similar technique on a larger canvas in her acclaimed Paris 1919.

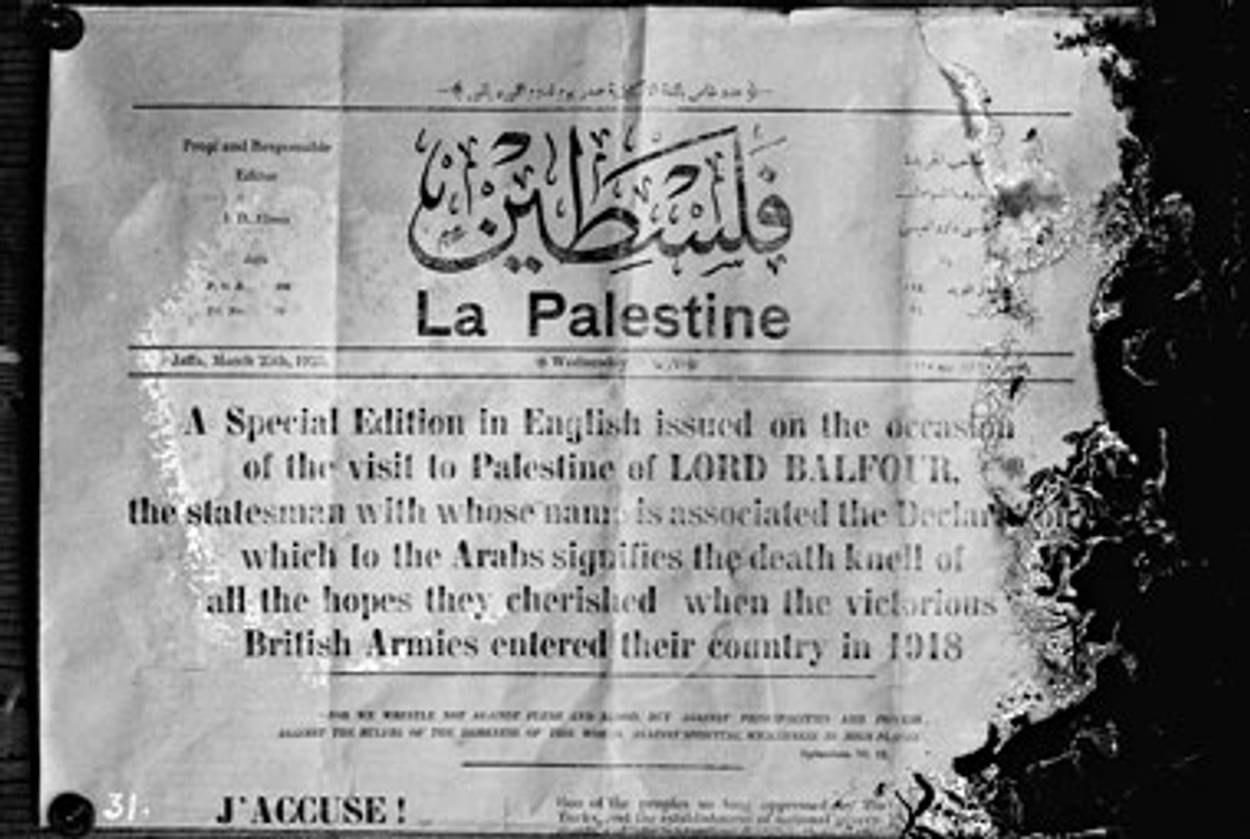

Jonathan Schneer, a professor of history at Georgia Tech, who specializes in British history, has gone in the other direction by focusing on one aspect of the complex diplomatic history of World War I in the Middle East. The Balfour Declaration—the British Foreign Minister’s letter to Lord Rothschild in November 2, 1917, stating that His Majesty’s Government “will view with favor the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine”—was a crucial step in the process that culminated in the establishment of the state of Israel 30 years later. The compelling story of how the British government came to issue that declaration has been told several times in book and essay form. What Schneer chose to do was to use his command of British history and to make a massive investment in fresh archival research in order to tell the story of the Balfour Declaration in the grand style of Fromkin and MacMillan.

The Balfour Declaration was to a considerable extent the achievement of Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann. Like some of his predecessors, Schneer describes well Weizmann’s charm and charisma, his ability to penetrate the highest echelons of Britain’s society, and his relentless, single-minded pursuit of his goal. But the Balfour Declaration was not merely a product of the Zionist leader’s personal exploits; it derived to a large extent from a cluster of British geopolitical interests and wartime considerations and calculations:

• The ongoing rivalry with London’s ally, France. Soon after signing the Sykes-Picot Agreement in May 1916, the British government regretted having agreed to a French foothold in an internationalized Palestine and sought to keep the French as far as possible from the Suez Canal. A Jewish national home under British protection would be the least awkward way of breaking the written commitment.

• Given the importance of oil and Britain’s anticipated position in Mesopotamia, London wanted territorial continuity to the Mediterranean and a secure high-quality port on its Eastern shore. Haifa was an obvious choice.

• British decision-makers overrated the importance and significance of “international Jewry.” As the war wore on they felt the need to obtain and maintain the support of Russia and America’s Jewish communities for the war. This tendency was reinforced by rumors of a comparable German initiative (think of the irony of counting on the Zionist sympathies of Trotsky and his other Jewish colleagues). The flip side of this consideration was the anti-Semitic views and sentiments of many members of the British elite as illustrated by Schneer.

Significant as these considerations were, the voyage toward the publication of the Balfour Declaration was anything but smooth. Several obstacles had to be overcome. One was the powerful opposition of the assimilationist anti-Zionist, Anglo-Jewish establishment, men like Lord Montagu (a member of Lloyd George’s cabinet) and Lucien Wolf who believed that a formal British recognition of a Jewish “nationhood” and the establishment of a Jewish national home would jeopardize the position that the Jewish community had finally achieved.

A second obstacle was France’s anticipated opposition to both the notion of Jewish nationhood and to British protectorate over a Jewish-Zionist entity in part of what the French had traditionally seen as their own domain in “Greater Syria.” Schneer rightfully assigns a cardinal role in his story to Sir Mark Sykes, and he describes in fascinating detail how Sykes in tandem with Weizmann and Nahum Sokolow artfully “sold” the idea to the French government. What Schneer failed to do was to consult the excellent book by Andrew and Kanya Forstner, France Overseas. Had he done that he would have presented Robert de Caix, the architect of French policy in the Levant, in a different light.

The most controversial aspect of Britain’s decision to promise Palestine to the Zionist movement concerns Palestine’s status vis-à-vis Britain’s earlier commitment to Sharif Hussein of Mecca and his Arab nationalist allies. This issue has been dissected and debated for decades now, and Jonathan Schneer goes through it with appropriate detail without presuming to settle the controversy, the essence of which is this: In 1915 the British government through its high commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, came to an agreement with Sharif Hussein, the custodian of the Muslim Holy Places in Mecca. Hussein was to stage a revolt against the Ottomans and was to be rewarded by the war’s end by becoming the head of an ill-defined independent Arab state. The British motivation was threefold: to neutralize the Ottoman’s Sultan’s call for Jihad, to subvert the Ottoman war effort (that proved to be much more resilient than expected), and to lay the foundations for a post Ottoman order in the Middle East.

In the course of his correspondence with Sharif Hussein McMahon explicitly excluded from the territory of the future Arab state “certain areas” that were not “purely Arab.” These areas were defined as “lying to the west of the district of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo.” This formulation clearly refers to Lebanon (France’s cherished prize), but what about Palestine? McMahon did not use the term “Vilayet” (province), so did he exclude Palestine, which lay west of the southern part of the Ottoman province of Damascus, or did he not?

The Arab nationalist claim was and is that Palestine was included in the commitment to Hussein. The Zionist claim is that it was not. If it was not, the Balfour Declaration did not constitute a violation of an earlier promise. The Balfour Declaration has been seen as an important element in building the Zionist case in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s (its text was incorporated in the League of Nations mandate for Palestine given to Great Britain), and it was therefore deemed important to present it in a positive rather than a dubious light.

The truth, as the book amply demonstrates, is that Britain misled everybody: the French—to whom they tried to deny not just Palestine but also inland Syria—the Arabs, and the Zionists. Schneer is at his most innovative when describing how after issuing the Balfour Declaration the British government empowered a series of intermediaries to negotiate a separate peace with the Ottoman Empire. The negotiators failed, but had negotiations succeeded they could have resulted in some form of continued Ottoman presence in Palestine. Weizmann and his colleagues were aware of some of these efforts but were reluctant to oppose an effort to limit the scope of the Great War.

Clearly Jonathan Schneer knows how to tell a tale in broad strokes and with attention to detail. Parts of the story have been told before, but telling it from a fresh angle embellished by new source material was a worthy effort. His achievement is marred by small irritants. When writing about Sokolow’s meeting with Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pius XII), Schneer writes that Pacelli’s “attitude toward Jews remains a matter of contention: He was not very helpful to Italian or foreign Jews during War World Two and his defenders argue that he did what he could.” This is peculiar leniency toward the pope whose passive attitude toward Nazi Germany and the Holocaust has been exposed by Saul Friedlander decades ago.

Schneer is equally lenient toward the Jerusalem Mufti, Hajj Amin al-Husseini. “Hunted by the British,” he writes, “he fled, landing finally in Nazi Germany during World War Two, where he sought Hitler’s support for Arab independence.” Anyone who knows anything about the Mufti’s close collaboration with Nazi Germany and support for the Holocaust would regard this as a gross understatement.

Schneer’s final lines tell us that the destruction of the Ottoman Empire led to national and ethnic violence. As in the case of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires, it is not certain that a series of warring nation states was a better alternative to the multi-national empires of the 19th century. These lines have an ironic ring to them, published as they are when the Islamist government of Turkey is pursuing what is described as a policy of Neo-Ottomanism.

Itamar Rabinovich is the Ettinger Professor of Middle Eastern History at Tel Aviv University and a Distinguished Global Professor at New York University.

Itamar Rabinovich is the Ettinger Professor of Middle Eastern History at Tel Aviv University and a Distinguished Global Professor at New York University.