Tagged

In Israel, graffiti tells all sides of the story

If the walls outside the Nocturno café in Jerusalem could talk, they’d probably tell you what they already say.

The area outside of the coffee shop is peppered with images and slogans that could only be found in Israel: a map of the country with the Palestinian areas removed; a soldier with the slogan “no legs, no problems”; a stencil of the national anthem, with the words changed (“the land of Zion and Jerusalem” has been replaced by “the land of Palestine and Jerusalem”). And, though Nocturno is a favorite hangout for art students from the Bezalel Academy, it’s hardly the only such canvas.

Graffiti has long been the focal point of the collective imagination here. In one form or another, it can be found everywhere from Hebron to Bethlehem, engaging both Israelis and Palestinians from all points on the political spectrum. Famously, it has also attracted scores of high-profile outsiders with statements to make, including the biggest names in the graffiti and street art worlds.

Israel has long had a unique passion for exchanging slogans in the street. In 2007, the country’s best-known hip hop outfit, Hadag Nahash, penned a tune in collaboration with the novelist David Grossman. Titled “Sticker Song,” it took its lyrics from the bewildering array of political slogans that can be found on bumper stickers up and down the country.

“These slogans are like capsules of Israeliness,” said Sha’anan Streett, the frontman of Hadag Nahash, when I met him at Nocturno. “They mirror the rhetorical ping-pong which is becoming a substitute for proper debate in a country that has lost any sense of hope.”

A similar sentiment haunts the walls 40 miles west, in the very different city of Tel Aviv. Locals have grown accustomed to images of the “Character,” a spindly, black-and-white vision of fragility, always struggling under an invisible weight, with a heart-shaped hole in the center of its chest. The Character is the creation of an Israeli artist who goes by the name Know Hope.

“The Character expresses the complex burden that Israelis grow up with,” said Know Hope, at his studio in Jaffa. “I weave moments of human fragility into a political statement.” Some of his best pieces, he said, are on the separation wall. One portrays the Character having his severed arm sewn together by a bird. Another has him pulling bandages out of his heart-shaped hole, on which is written: please believe. Later, beside a downtown café, I find another of his pieces: the Character holding a weeping bird to his mouth, as if about to breathe life into it—or devour it.

Several hours north, in the settlement of Hebron, the graffiti looks quite different. In 2001, the IDF closed down a Palestinian market that was built on disputed land, as it had become a flash-point of violence. This has had a profound impact on the local economy, and now the place is a ghost town. On the rows of boarded-up shops are strings of spray-painted Stars of David, accompanied by belligerent slogans, the most radical of which—“death to the Arabs”—has been (badly) painted out.

In the Palestinian territories, the graffiti is dramatically different again. According to Matt Rees, a crime author and former Jerusalem bureau chief for Time magazine who accompanied me across the checkpoint, graffiti in Palestine tends to be linked to the militant groups. Slogans there are color-coded according to faction, he said: Yellow for Fatah, red for the PFLP.

On a recent afternoon, Rees and I passed through a little-used checkpoint into the West Bank. As we entered the Duheisha Refugee Camp, all around us were graffiti portraits of Intifada-era martyrs. Most prominent of these was an imposing image of Ayat al-Akhras, the third and youngest female suicide bomber, who lived her whole life here. The unsigned portrait, completed in 2002, has been recently given a fresh lick of paint.

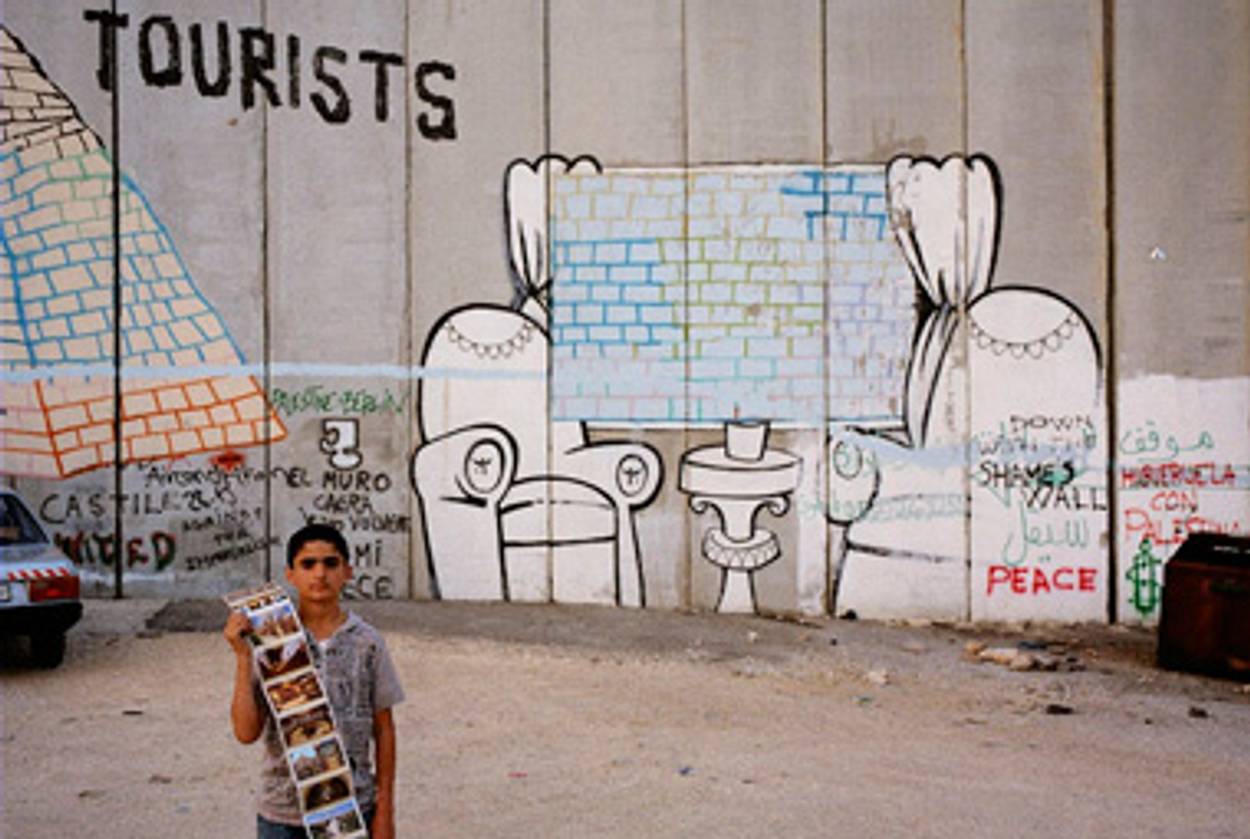

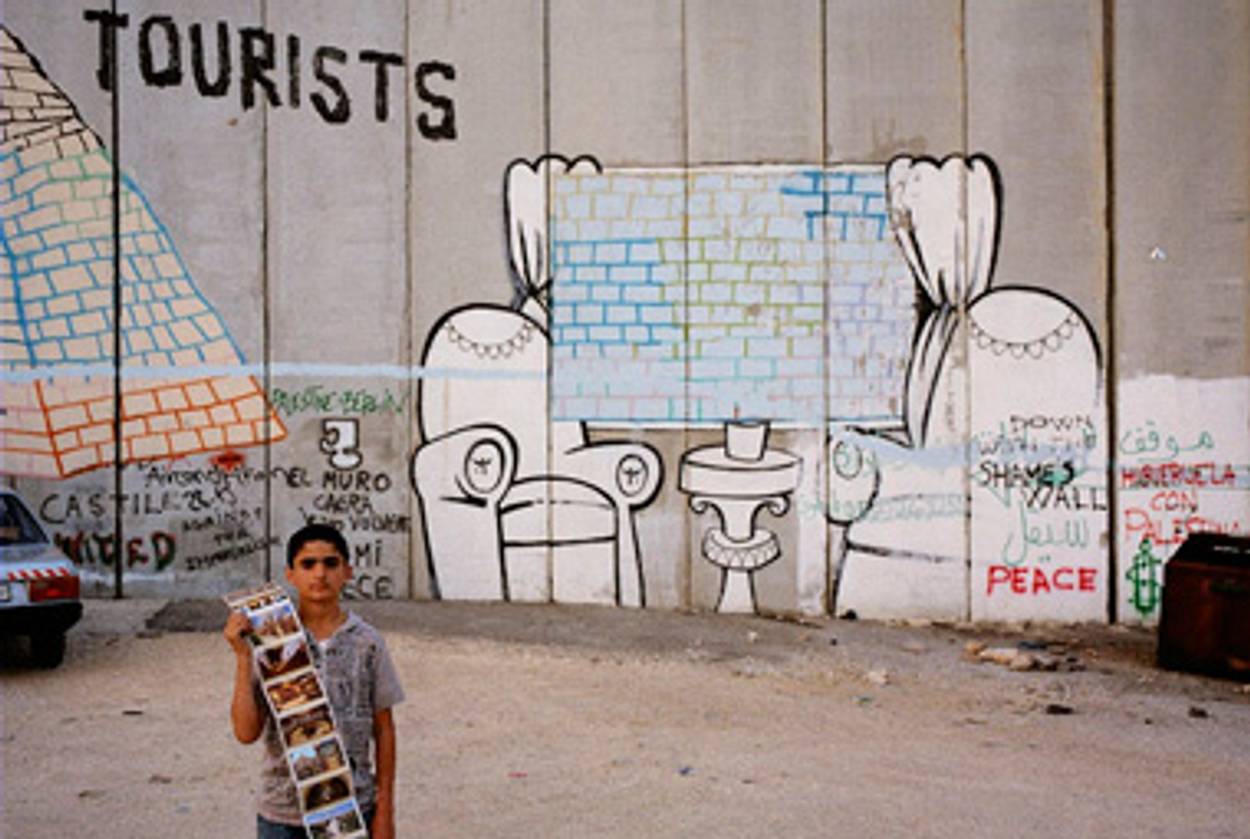

Perhaps the most famed piece of graffiti in the region is located on the nearby partition wall, a part of which has become a Mecca for international graffiti artists since the reclusive British sensation Banksy painted here five years ago.

Banksy’s work brought the region prominence and with it the possibility of commercial advantage. Rees introduced me to two Palestinians, one of whom said he used to be a bodyguard for Yasser Arafat. They took us to a location where they had stashed a piece of a wall from someone else’s house. On it is an original Banksy: a soldier frisking a donkey. Although they worry about Palestinians being compared to animals, they wanted to sell it. “We will use the money for the children of Palestine,” the ex-bodyguard told me.

But graffiti in the region doesn’t only get inspiration from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—it’s also used as a language for domestic Israeli issues. In Jerusalem, in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhood of Meah She’arim, the anti-Zionist ultra-Orthodox Neturei Karta sect has plastered the neighborhood with anti-statehood slogans.

“God wants the State of Israel to be totally dismantled,” says Yoel Kroiz, a leading figure in the radical organization. “Since the establishment of the State of Israel, we haven’t had one day of peace. Jews should be living as a minority within a Palestinian state. That’s the only way to end the conflict.”

Kroiz, who was detained last year for an alleged tear gas assault on a woman he considered immodest, sees himself as part of a long tradition. In his cluttered quarters, he showed me his dust-covered collection of Orthodox street-posters, which stretches back over 90 years. Among the religious edicts and signs protesting the desecration of ancient graves is his anti-Zionist collection. “We mourn the existence of the State of Israel,” says one. “Arabs, yes, Zionists, no,” reads another.

On a wall a little further down the road, the two extremisms are in collision. “Death to the Arabs” has been scrawled on a wall by a member of the hardline settler movement. An ultra-Orthodox radical has crossed out “death,” changing the slogan to “Palestine to the Arabs.” The conflict of views here—all types of views—is nowhere as clear as on its ancient walls.

Jake Wallis Simons is a U.K.-based novelist, journalist, and graphic artist.

Jake Wallis Simons is a U.K.-based novelist, journalist, and graphic artist.