The Joy of Stats

The brainy, numbers-crunching Jewish fans who’ve revolutionized pro sports and realized every geek fan’s dream are celebrated as heroes at the annual MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference

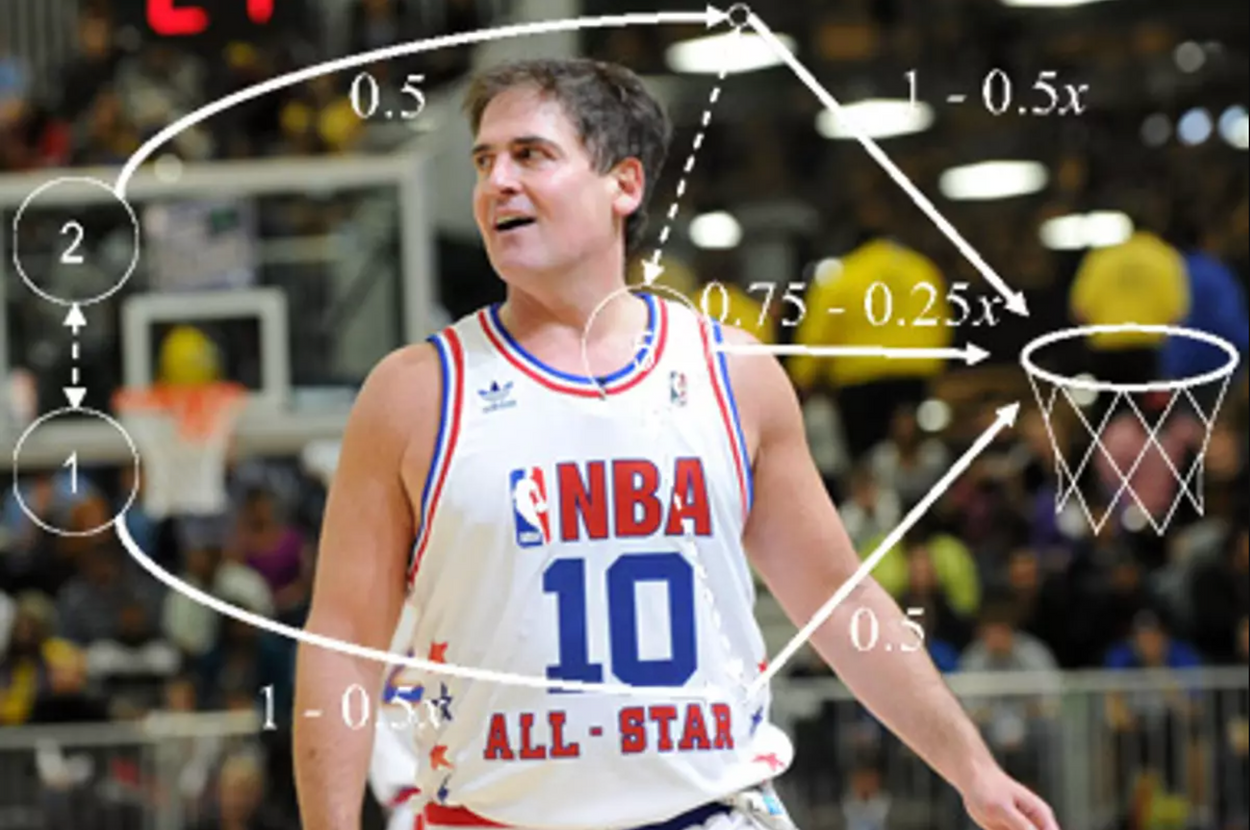

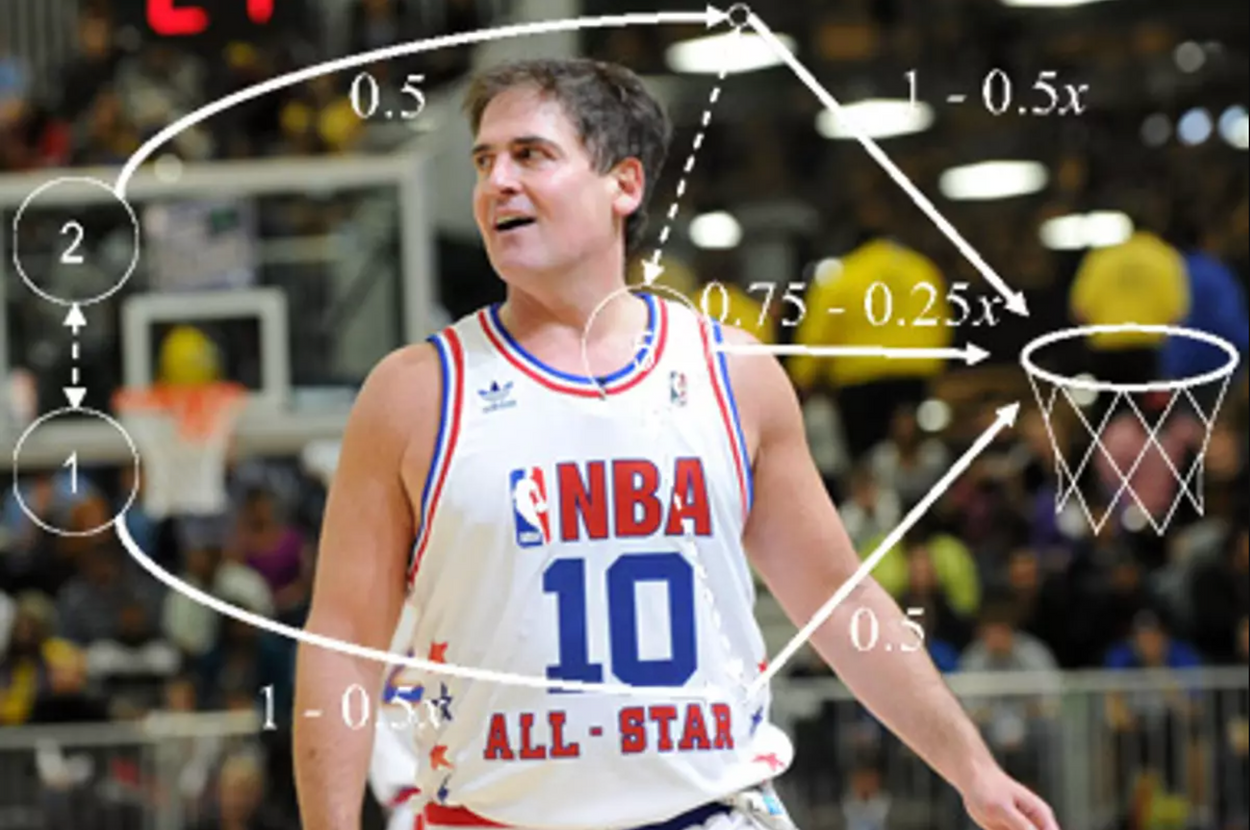

I spotted Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban in the crowded hall almost two hours before the first of two panels he was participating in was scheduled to begin. He had no apparent handlers, but the crowd at the fifth annual MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference knew to make way for him and his shock of black hair. He is a few inches north of six feet, but what you most notice about his physical appearance are his biceps, which bulged from the sleeves of an inexpensive-looking gray T-shirt that bore the words, “Talk Nerdy To Me.”

The Sloan conference—its host is MIT’s Sloan School of Management—is the foremost gathering for sports professionals, journalists, and fans interested in the most cutting-edge ways of viewing and analyzing sports. Cuban, who made a fortune in the high-tech boom of the 1990s and then bought the majority share of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team in 2000 for nearly $300 million, is the poster boy for the sports-geek culture that found its nirvana on March 4 and 5 at the Boston Convention Center, a metallic, antiseptic hulk in an ugly, picked-over section of downtown Boston. New York Giants defensive lineman Justin Tuck and the Olympic gold medalist speed-skater Apolo Anton Ohno were there. Malcolm Gladwell, ESPN’s Bill Simmons, and basketball coach turned television commentator Jeff Van Gundy were all there. Indianapolis Colts coach Jim Caldwell—the guy who gets to tell Peyton Manning what to do—was there, as was Daryl Morey, the high-profile general manager of basketball’s Houston Rockets—in fact he was the co-chair of the conference.

But no one attracted more attention than Cuban, who gives the impression that he was motivated to buy a sports team by roughly the same sentiment that moved Charles Foster Kane to purchase the New York Inquirer: “I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.” After Cuban once remarked that the NBA’s head of officiating “wouldn’t be able to manage a Dairy Queen,” he later expressed regret for the damage his comment caused the ice-cream chain and volunteered to work at one for a day—the sort of gracious, clever stunt you could see yourself pulling if you, too, ruled the world.

To the fanboys who paid $400 (or maybe the $100 student rate) to attend the conference, Cuban is plausibly one of them.

To those who dream of future front-office success in sports, Cuban is the apotheosis: owner of a perennial contender. The Mavericks have won more than 50 games (of 82) in each of the 11 full seasons Cuban has been the team’s majority owner, and in each one of those seasons they’ve been one of the eight teams (of 15) to qualify for the playoffs in their conference. (It’s a streak only the San Antonio Spurs, the Mavs’ bitter rivals, can match.) This year, the Mavericks went 57-25, good for the Western Conference’s third seed, and are currently up three games to two in their first round playoff series, against the Portland Trail Blazers.

To undergraduate business majors and slightly older business students—in their gray suits and with their consultants’ vibe—Cuban is the guy who arrived in Dallas in the ’80s and saw that while the J.R. Ewings had cornered the oil market, there was money to be made in the burgeoning technology business. He proceeded to make this money and then buy the Mavs, a relatively young organization playing basketball in a football town, and remake them into the sixth most-valuable franchise in the NBA.

To the stat geeks—the conference’s original fan base, who these days toil less frequently in basements and more in professional front offices—Cuban is an acknowledged patron and a kindred spirit, someone who not only perceives their utility but would be one of them if he wasn’t instead spending his time making much more money than they do and appearing on Entourage. “Cuban’s special,” Aaron Schatz, arguably football’s top outside statistician and a difficult man to impress, said appreciatively. “I think most owners who meddle in their teams are very old-school. Cuban meddles in a teach-me-something-I-don’t-know way.” Nate Silver, a former baseball analyst, agreed: “There are owners who are still old-boys culture, but he’s not a part of that.”

And of course there were the Jews.

Everyone at the conference was Jewish—and by “everyone” I mean that while Jews comprise 2 percent of the American population roughly every third person at the conference was Jewish. I met some kids from the Harvard Sports Analysis Collective, a group of terrifyingly bright 20-year-olds, and quickly learned, to my lack of shock, that most of them were Jews. The business majors and the MBAers were Jews; one conference organizer, a Sloan student with a distinctively Irish name told me how glad he was I was writing this story, because clearly everyone there, himself included, was Jewish. The journalists covering the conference were Jews. And Cuban—his family name was Chopininski—is Jewish, too. This matters.

***

Roughly a decade ago, the notion that there was a cutting-edge way to view and analyze sports materialized in the public consciousness when Michael Lewis’ book Moneyball sold half a gazillion copies and spawned even more conversations at bars, stadiums, gyms, classrooms, and every other place American men congregate. Moneyball described how Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane used insights gleaned from sabermetrics—the advanced statistical study of baseball—to take the meagerly financed A’s to three consecutive postseasons. (But he never made it to the World Series: “My shit doesn’t work in the playoffs,” Beane famously admitted, an instant entry into the quotes-we’d-need-to-invent-if-they-didn’t-exist Hall of Fame right beside “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”)

Advanced analytics has since made its way to the other professional sports, so that now even the casual fan is aware that an at-bat that results in a walk is nearly as valuable as an at-bat that results in a single and that a basketball player can be a major asset to his team even if his traditional numbers, such as scoring, are unimpressive. “For a long time, it was pretty niche,” Sports Illustrated’s Joe Posnanski, perhaps the foremost practitioner of sabermetrics in journalism, told me. “But now, even people who would claim not to be interested in the numbers would use things like OPS”—that’s on-base percentage plus slugging percentage—“which may be basic in the advanced world but is much, much more sophisticated than batting average, RBIs, and home runs.”

The stats craze was in part an inevitable iteration of the Internet’s democratization of knowledge. “We live in an environment now where there’s a lot of open data, which makes people less tolerant of letting people be gatekeepers,” argues Silver, who at Baseball Prospectus was a top sabermetrician and has since abandoned baseball metrics in favor of predicting elections for the New York Times. “It’s not that radical, really, right? But in some ways it’s been very encouraging—if you believe in mass knowledge, you definitely have seen progress.”

More to the point, the democratization of knowledge has redefined both the professionals and the fans by bringing them closer together—and, in the person of Mark Cuban, arguably making them one and the same. “There’s a geekification going on of sports,” Malcolm Gladwell told me a couple of weeks before the conference, where he would moderate the opening panel discussion. “In the beginning, the fan was a relatively passive figure. You have all of these things that are turning the fan into an actor—fantasy sports, all this statistical stuff.” Being a sports fan today entails not only rooting for your team but affirmatively conceiving what your team could be doing better; using ESPN’s trade machine to make hypothetical trades allowed by each team’s salary cap situation and each player’s contract; and fundamentally understanding how the sport really operates in a way that even hardcore fans of a quarter-century ago could not have imagined.

Continue reading: the world’s biggest Mavs fan, Football Outsiders, and “additional ways to analyze things.” Or view as a single page.

“It’s outsiders,” Gladwell added, “people who have nothing to do with the teams, creating their own version of reality, reordering our understanding of who’s good and who’s not in a really radical way.” However, as the conference visibly demonstrated, the outsiders are no longer exclusively outside. Spurred by the statistical revolution in sports analysis that began in baseball, fans with no background in sports are becoming sports professionals, and these professionals are turning to those disciplines that were previously rigidly segmented from sports—business, math, finance, psychology, even wit—in the search of a slight edge. Mark Cuban can be confounding if you are locked into the old paradigm of the benign old-boys-club owner, or even the paradigm of the Steinbrenner-esque madman. But in this new era, he makes sense. The next time you see Cuban high-fiving his players behind the bench or mouthing-off about the officiating, just think of him as what he is: the world’s biggest Mavs fan.

***

Sports have always been one of the primary avenues through which Jews (mainly Jewish men) have managed their acculturation into American life. The 1930s and ’40s saw American Jewish athletes like baseball slugger Hank Greenberg, star quarterback Sid Luckman, and boxer Barney Ross become national heroes and symbols of Jewish social acceptance and ethnic pride. However, subsequent elevations of class status led Jews to perceive athletic performance as a base pursuit to be shunted aside in favor of those professions that, well, Jewish mothers urge their boys to pursue. This happened for a few generations. Then, sometime over the past few decades, Jews did even better for themselves than their mothers could have ever possibly hoped for, and as they looked around, wondering what to do with this surplus time and money and expertise, they turned to sports. Unlike other rising ethnic groups, such as the Irish and the Italians and, in a different way, the African-Americans, who continued to have athletic heroes to identify with and take pride in even as the more maternally driven members of their tribes achieved mainstream success, Jews saw sports as a purely leisure-time activity and saw themselves as spectators rather than athletes. So, they set about creating this new fandom in order to utilize during their leisure hours the same education and work ethic and angular creativity and intellectual brawn that had helped them attain material success (and please their mothers).

Of the figures who have made the biggest difference over the past half-century in advancing the professionalization of the fan (and the fan-ification of professional sports), nearly all were Jews. Strat-O-Matic—essentially a video game before video games (or videos), in which players played nine innings of baseball with the same iron statistics that prevailed on the diamond prevailing at home around the kitchen table and rolls of dice substituting for the day-to-day luck of actual players—was created by Hal Richman, a member of the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. Fantasy sports, both as a concept generally and as a specific game—in which you assemble a group of players and your friend assembles his own group of players and the winner is the person whose group produces superior statistics that week, or that season—was invented by Daniel Okrent, who would become the first public editor of the New York Times, and a group of other writer types over lunch in midtown Manhattan. Many, many years later, after sabermetrics had been invented, a die-hard Boston Red Sox fan named Theo Epstein emerged from Yale to become his favorite team’s general manager before he was 30. In 2004, Epstein was the first sabermetric-savvy GM to preside over a championship (not to mention the first Red Sox GM to preside over a championship since 1918). The NBA has arguably the most stats-happy ownership, led by Cuban. The best statistical analyzer of football is Football Outsiders, an outfit founded by Aaron Schatz. For a while, baseball’s leading sabermetrician was arguably Baseball Prospectus’ Silver—who, he told me, is actually only half-Jewish—until he decamped to become everyone’s favorite elections-predicting guru; now it is probably Phil Birnbaum, an independent sabermetrician. For years, Ken Tremendous—the nom de blog of Michael Schur, a writer for The Office and now Parks and Recreation—fought the battle for advanced stats on a totally different front, using his hilarious and sadly defunct blog, Fire Joe Morgan, to belittle those who, like its namesake, refused to accept the obvious superiority of the statistically savvy way of viewing things.

There are only two important characters in this story who aren’t Jewish. Billy Beane, Moneyball’s main subject, the first person to bring advanced stats to any major sports team’s front office, is the exception that proves the rule because he is not a fan or former fan, but a former player—one of the jocks. Beane was driven to look for players who help teams in ways that other franchises hadn’t figured out yet—specifically, guys whose lean batting averages and dumpy physiques masked brilliant on-base percentages and above-average defensive skills. (Beane was an average-to-below-average player.) The other crucial link is Bill James, who is simply an exception. Roughly three decades ago, he began writing obsessive prospectuses in which he invented sabermetrics, igniting, with his acrobatic intellect and charismatic prose, the stats revolution.

As a brief example, take the Tampa Bay Rays. In the past few years, the team has become the toast of baseball’s most forward-thinking fans and professionals through its use of innovative analytics; the Rays are the subject of a new book by Jonah Keri (also of Baseball Prospectus, also Jewish) called The Extra 2%—as in, if you manage a baseball team really wisely, you can score an additional 2 percent return on your investment. The three front-office guys who came to Florida after the team’s dismal 2004 season were used to thinking in terms of investments and returns, having, as Keri puts it in his book, “landed in baseball straight from jobs on Wall Street” at firms like Goldman Sachs and Bear Stearns; the new owner had started, like Cuban—author of the book’s foreword—as a tech entrepreneur. The owner is Stuart Sternberg; the two financial wizards he brought with him to run the team—which is to say, to create the superb farm system, implement the innovative on-field strategies, and sign the hugely advantageous contracts that allowed the team with the American League’s lowest payroll to represent that league in the 2008 World Series—were Matt Silverman and Andrew Friedman.

***

There is a depressing moment near the end of Keri’s book, which was published last month. It is the winter of 2010, 18 months after the Rays (payroll $43.8 million) finished the 2008 season with the league’s second-best record and then defeated two differently colored Sox, one from Chicago (payroll $121.2 million) and one from Boston (payroll $133.4 million) before going down in five games to the Philadelphia Phillies (payroll $98.3 million) in the World Series. The next year had gone differently, with the New York Yankees (payroll north of $200 million) duly winning the American League East and the World Series and the Red Sox securing the wild card spot. That extra 2 percent will only get you so much when you are investing one-third what your competitors are, especially when your competitors also try to imitate your successful strategies. In Keri’s book, Silverman finds himself at a panel at last year’s Sloan Conference and, spying a nearby Red Sox jersey, grabs it. “They’re always looming,” he tells the crowd.

The conference is where one goes to try to maintain the 2 percent advantage. “There’s always going to be additional ways to analyze things,” said Jessica Gelman, who co-founded and co-chairs the conference with the Rockets’ Morey. Gelman is vice president of customer marketing and strategy for the Kraft Sports Group—which is to say, the New England Patriots. Which is to say: She’s a genius. She is also tall and attractive, with curly dark-blonde hair and a look that communicates that she cares what you’re talking about, but—you’ll have to excuse her—there are also four other things she has to think about, too. At Harvard she played point guard, and they won a couple of Ivy League titles, she told me in her laid-back Gen X lilt. Later, she played for a year in Israel’s professional women’s basketball league. Which is to say: Jessica Gelman is awesome.

Continue reading: “Dork Elvis,” fans’ new-found empowerment, and game management. Or view as a single page.

People who were at the first Sloan Conference—this year’s was the fifth—speak of it as one of those bizarre, weird, horrible parties that was nonetheless a major bonding experience; you shoulda been there, man. They huddled at desks in cramped classrooms and walked from building to building in the snow.

The conference entered primetime in 2009 after Bill Simmons attended and famously labeled it “Dorkapalooza ’09.” (Morey, his friend, was “Dork Elvis.”) This year, for the first time, the conference lasted two days instead of one, and this was the first time attendance swelled to 1,500. ESPN is a primary corporate sponsor. “It’s like the most fun you can have at anything that’s called a conference,” Silver told me beforehand.

On Friday, I attended the opening session, “Birth to Stardom: Developing the Modern Athlete in 10,000 Hours?” The panel was moderated by Gladwell and included Morey and former Rockets coach Van Gundy basically making fun of the shooting guard Tracy McGrady, last decade’s archetype of the fabulous flameout. The conference was split into 75-minute blocks, with 15-minute breaks between sessions. During some of the blocks, I sampled several events, grabbing a few minutes from one panel, a few more from a lecture, and spending the rest of the time among the steady stream of people in the hallway. I saw Tobias J. Moskowitz, co-author of the new book Scorecasting—he met his co-author, L. Jon Wertheim, he later told me, at Jewish summer camp—give his spiel on “The Real Reasons Behind Home Field Advantage.” (There’s actually only one, he says: It’s the refs, stupid!) I dabbled at the “Basketball Analytics” panel, which featured Cuban. Saturday morning, I ducked in briefly to the “Business of Sports” panel to see Sunil Gulati, an incredibly short and incredibly charming silver-haired Indian-American who is the president of U.S. Soccer and was my Economics 101 lecturer when I was a freshman. I sampled various booths in the trade show that spread out across the blocks-long second-floor hallway, where exhibitors included StarStreet: The Sports Stock Market; Are You Watching This (which lets you know if any exciting games are on, and how exciting these are according to a scale of “OK,” “Good,” “Hot,” and “Epic”); StatDNA (“The world’s most advanced soccer data and analysis”—from which you can deduce that the advanced work in soccer is being done in virtually the only country that calls it “soccer”); Sports Data Hub; and eThority.

There was an unusually small room at the northwest end of the hall devoted to the authors of research papers. Here are the names of some of the papers: “Paired Pitching: The Welcomed Death of the Starting Pitcher”; “Optimizing an NBA Team’s Approach to Free Agency Using a Multiple Choice Knapsack Model”; “A Groovy Kind of Golf Club: The Impact of Grooves Rule Changes in 2010 on the PGA Tour”; “An Improved Adjusted Plus-Minus Statistic for NHL Players”; “A Major League Baseball Swing Quality Metric”; “The Effects of Altitude on Soccer Match Outcomes.” There is no way David Foster Wallace did not come up with at least one of those titles.

The “Football Analytics” panel, Friday afternoon, was my favorite. “This is a panel with five white male panelists,” said Gary Belsky, editor-in-chief of ESPN The Magazine, to begin things. What he didn’t mention was that four of them were Jewish, and the fifth, Eric Mangini, an NFL head coach, most recently of the Cleveland Browns, falls under the jock exception to the Jews rule. Mangini looked polished in a shiny dark suit and red tie. There were two execs—Adam Katz of the Philadelphia Eagles and Alec Scheiner of the Dallas Cowboys—tan, dark-haired men in glasses who kind of looked alike; Belsky; and Schatz, who sat in the middle, long hair back, beard-and-mustache messy, legs spread in an obtuse angle, water bottle nestled in front of his crotch, looking like an unbelievably satisfied hippie.

They spent much of the time talking about game management, the term of art for the practice of exploiting the flow of the game—when to spend each half’s three precious timeouts; when to challenge a ref’s call; when to attempt a two-point conversion. The odd thing about game management is it does not require the savant-like football expertise that nearly all head coaches possess; in fact, some of the best head coaches have decidedly poorer understanding of game management than the average fan does. (Simmons has suggested that each coach hire a teenager who plays video games all day as a game management consultant, and he is not wrong.) Andy Reid, coach of the Eagles, and Norv Turner, of the San Diego Chargers, routinely design offensive attacks of a complexity that no fan can comprehend while also routinely making idiotic decisions regarding timeouts. Game management is thus a perfect example of the increased access fans have to once-privileged information. Where before we silently cursed the dumb coach in our living room while remaining unsure whether we were pissed because we were right or because we had had four beers, today we take to the Internet and find thousands of people who also think we are right, and some more who have done the math that demonstrates that we are right, and therefore we know. When Mangini, an unusually thoughtful football coach who is cognizant of the analysts’ contention that teams ought to punt the ball far less frequently, demurred that he is still liable to make in-the-moment, even gut decisions, Belsky replied, “But you sound like a blackjack player!” This is, after all, a fans’ world, and Mangini just coaches in it, at least when he is employed.

At the panel’s close, Schatz noted that somebody in the audience had written on a sign that the NFL owners and players, who were set to lock out/be locked out in a couple of hours, had agreed to a one-week extension. In a perfect metaphor for fans’ newfound empowerment, the panelists, performing for us on the stage—and thereby banned by decorum from reaching into their pockets, pulling out their BlackBerrys, checking their Twitter feeds, and learning the news—were in the dark, and it was up to some random guy to inform the senior vice president and general counsel of the Cowboys (Forbes valuation: $1.8 billion) of the most important development to take place in his job in the past month. (One week later, the talks dissolved, and the owners and the union are now in court.)

The most anticipated panel was at 4:15 p.m. on Friday. Its title was dull—“Referee Analytics”—but it offered Cuban, NFL referee Mike Carey, and Bill Simmons discussing sports officiating, a topic on which Cuban has been known to be vocal. “Mr. Cuban,” Simmons said, “I can’t believe you’ve come on this panel.”

Cuban’s passion has gotten him in hot water. He complains about refs as though he is a fan, but he is not a fan, he is an owner, and he is therefore subject to league rules against questioning officiating, violations of which have cost him millions of dollars in fines levied by the commissioner’s office. “I got an email from the league saying it’s a public forum and there would be an intern watching,” Cuban replied to the crowd. Everyone laughed. Cuban smiled, too, but he was serious.

Continue reading: Cuban, owners worth millions, and the game of life. Or view as a single page.

Cuban has hired people to analyze which individual referees make what calls—the league records only which penalties are assessed against which players—and discern patterns in that data. By definition, then, he is a referee analyst, and he offered one of the best defenses of this field of advanced metrics—or, really, of any field of advanced metrics—that I have heard. “Everybody’s got a different skill set, and I wanted to be aware of each official’s skill set to the best of our ability,” he told the crowd. Perhaps certain refs are simply “better” at calling three-second violations or “better” at calling offensive fouls, much as certain basketball players are better at making uncontested three-point shots or better at forcing opponents to turn the ball over. If Cuban knows which ones they are and other teams don’t, that might be worth three points in one game, which might be worth one more win, which might be worth one more home-field advantage in the playoffs, which might be worth the championship. And since only one team out of 30 will win the championship, it is far from outlandish to pour real resources into obtaining even the tiniest of edges. No wonder Cuban looked so pleased onstage, chewing gum as though in conscious effort to keep his mouth shut about the blatant imperfections and occasional scandalous biases of NBA refs. How sweet it will be when he gets his championship—and his last laugh.

***

On Saturday morning, I attended the “New Sports Owners: The Challenges and Opportunities” panel, moderated by Jessica Gelman. Simmons was back, but much quieter; he was joined by Joe Lacob, the relatively new owner of basketball’s Golden State Warriors; Jeff Moorad, who is the relatively new owner of baseball’s San Diego Padres; and Wyc Grousbeck, the less relatively new co-owner of basketball’s Boston Celtics. Lacob was in town to see his mediocre Warriors, and, naturally, they’d lost the night before, 103-107, to the Celtics, who would later secure the Eastern Conference’s third seed and who have just swept the New York Knicks to make the second round of the playoffs for the fourth consecutive season. Grousbeck opened the panel by sarcastically shoveling the shit of last night’s defeat into Lacob’s mouth while the Boston crowd cheered. Lacob took it good-naturedly, though I didn’t see why he should have.

After the panel, Lacob was in the hallway for the next hour-and-a-half, talking to whomever wanted to talk to him. Sometimes these people looked fairly important; other times they were kids, all light-blue oxford shirts and acne. I departed when Lacob did, around 12:30 pm—he got his bag and coat from the check immediately before I did—and I watched him wheel out, alone, a shortish man with tan skin and brown hair combed over what’s maybe a bald spot in the middle of his head, trying to figure out which exit of the vast, empty first floor of the Boston Convention Center would most quickly lead him into the cushioned seat of a cab. This is insane, I thought. And it was. Joe Lacob is worth millions, all of it self-made. Dude could have been anywhere. But he was at the Boston Convention Center at 9 in the morning on a Saturday in early March. Why didn’t he just stay in what is, after all, the Golden State? Or if he wanted to travel with his team, why wouldn’t he sleep in, or go eat a $60 brunch at one of Boston’s finest dining establishments? Why go, and then stick around talking to whomever wants to talk? How much of an “edge” could his team really get from that? And even if there is a slight edge to be gained, or the potential for one, well, it’s only sports.

To which the reply comes: Well, it’s only life. For a while, it astounded me that NFL quarterbacks are among the most scrutinized people on Earth despite the fact that they are actively relevant for roughly a few hours on precisely 16 days each year (and a few more hours on a few more days, if your team is really good). But I’ve learned that we do this to quarterbacks because we also do it to ourselves. We spend an astonishing amount of our waking hours establishing, mundanely, the foundations of a few happy moments. We expend massive chunks of time on our apartments or houses so that when we arrive home each day, the first 30 seconds will be slightly more pleasant. If we are lucky to have jobs we enjoy, these still mostly involve positioning ourselves for the comparatively few moments of triumph that make them worthwhile. We work to make money, and deprive ourselves of certain things to save more, so that we can travel someplace nice every few months, or eat an especially satisfying meal every couple of weeks, or buy someone we like a nice gift for her birthday. Yet it’s all worth it, partly because it has to be. When Lacob (not Jewish, alas) or Cuban or Okrent or Epstein or Schatz or you or I treat sports as though it is any other immaterial, bottom-line discipline—all while maintaining the crucial double consciousness that sports are one of life’s pleasures, and something we do “just for fun”—we are not making sports into something just as joyless as the rest of life. We are making sports into something just as joyful as the rest of life.

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.