Mob Tactics

Egypt captured Israeli-American Ilan Grapel to generate popular support among the volatile anti-Western middle class at home

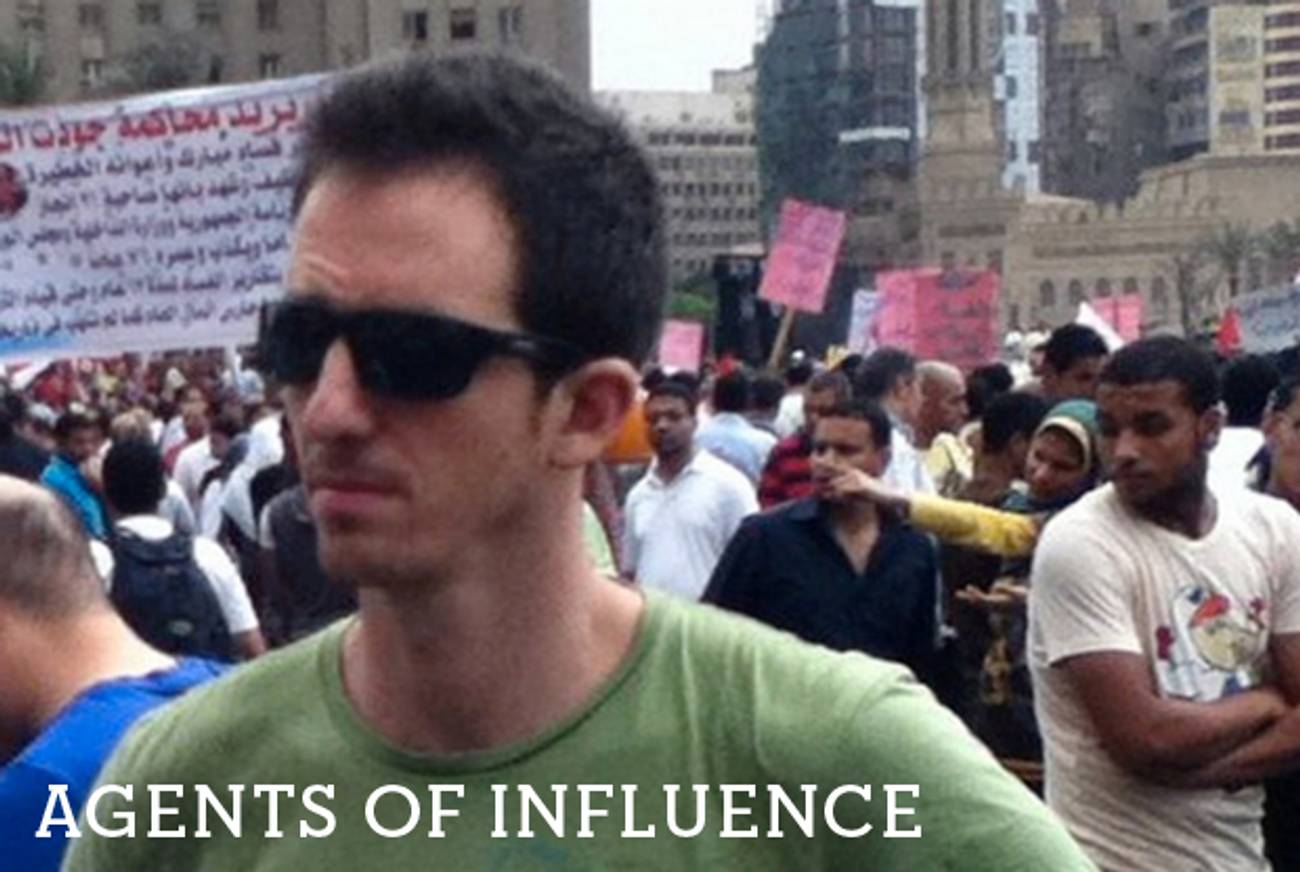

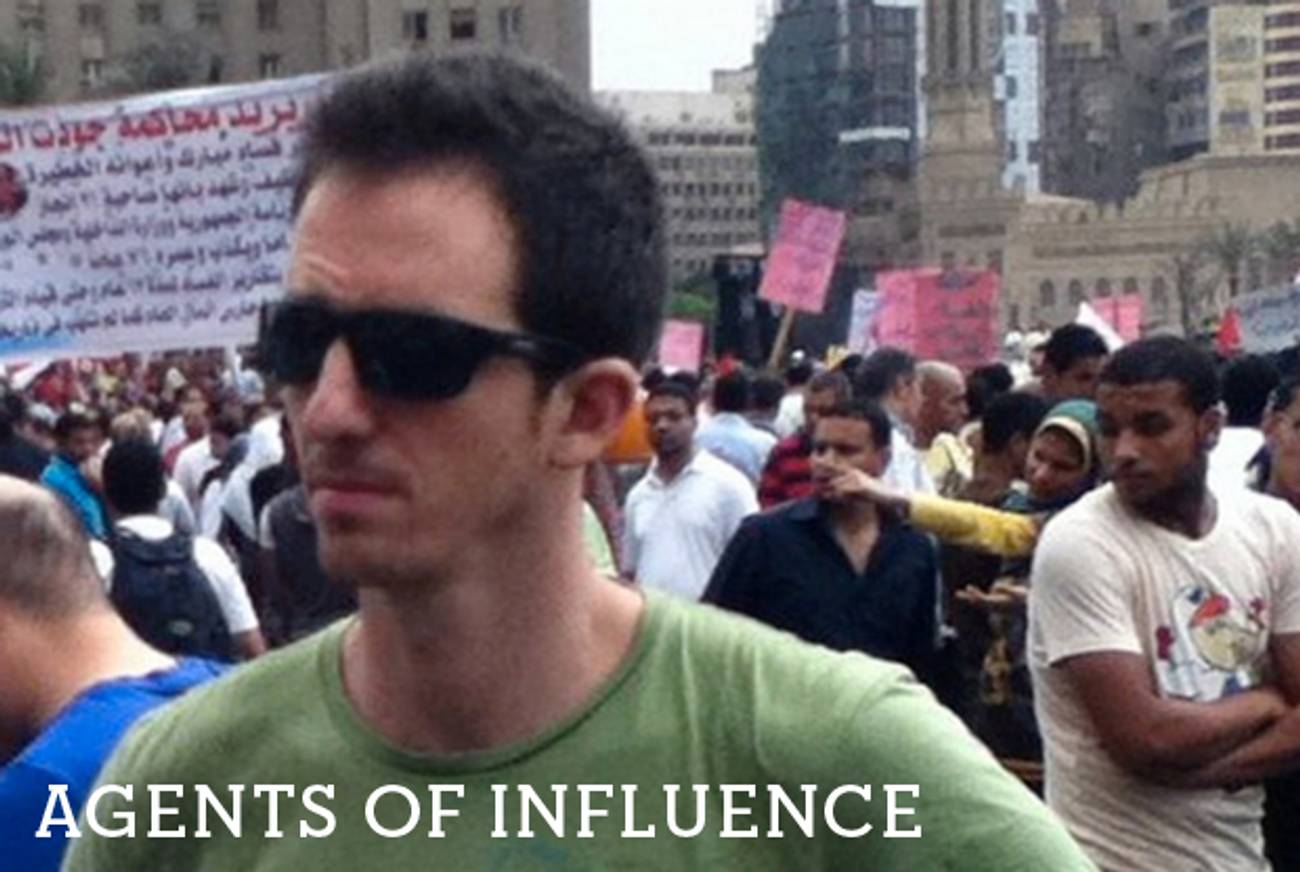

Headlines this week may be fixated on Libya’s embrace of Sharia law and Islamists’ electoral victory in Tunisia, but if you really want to gauge what the Arab Spring has wrought, forget about the drama in Tunis and Tripoli. Consider instead the unfolding story of 27-year-old Ilan Grapel, an Israeli-American law student who has been held on charges of espionage for the past four months in Cairo.

Yesterday Israel approved a deal, seemingly hastened by the Gilad Shalit prisoner swap, which will free Grapel in exchange for 25 Egyptian prisoners. And if all goes according to plan, Grapel will be released Thursday. Some former U.S. intelligence officials believe Grapel may really have been an Israeli spy, but Israeli soldiers, never mind the Jewish state’s clandestine agents, are seldom returned alive. The Egyptians know he’s not a spy, but he’s a valuable card anyway, which is why they captured him. It is logic and behavior befitting a terrorist organization.

If Hamas and Hezbollah can get the Zionist entity to release their associates, the thinking goes, why can’t Egypt’s interim ruling body, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, do the same for Egyptian prisoners? The problem in the Middle East, then, isn’t that the Islamists are on the verge of taking over and thereby transforming Arab societies. The problem is that these societies are already governed by the passions that make the Islamists so popular.

Longtime U.S. ally Hosni Mubarak, the former president of Egypt, would not have dreamed of taking an American citizen hostage. It’s true that things have changed in Egypt, but let’s not overstate the case: Grapel’s arrest is not a sign that the Supreme Council of Armed Forces is joining hands with Iranian-backed terror organizations. The purpose of the exchange, from Cairo’s perspective, is to placate the mobs that have already laid siege to the Israeli embassy, burned Coptic churches, and may in time cause even worse problems for the ruling military council. The way to calm the situation, they believe, is to show that Egypt’s problems are manufactured by the West, and that Cairo’s ever-competent rulers managed to unearth a plot before the foreigners could once again unleash their mayhem.

Why Cairo chose Grapel as its test case seems to be merely a matter of convenience. Yes, the Queens native served in the Israeli Defense Forces in the 2006 war, where he was injured fighting Hezbollah. Yet the fact that Grapel, a law student at Emory University in Atlanta, had taken a job in Cairo in May with St. Andrew’s Refugee Services, a Christian organization that mostly provides legal aid for Sudanese refugees, is perhaps what first attracted the attention of Egyptian authorities. African refugees—Christians and Muslims—are a sensitive issue for the Egyptians, not least because their mistreatment in Egypt has caused many of them to flee to friendlier vistas across the border in Israel.

While some believe the Shalit deal set the precedent for the Grapel exchange, it’s a mistake to see the two cases in the same light. For Israel, the point of freeing a thousand prisoners in exchange for one is not merely a moral calculation, but also a form of strategic communication intended to dishearten Israel’s foes. The message it sends is not only that Israel values life above all, but that the Jewish state can afford to put its enemies back on the street because in the end, no matter how numerous, those enemies have no chance of winning.

The Grapel deal is something else—straight-up extortion with domestic political benefits. For Egypt, getting prisoners released for Grapel is more like Libya winning intelligence agent Abdelbasset al-Megrahi’s freedom from the Scottish government as part of an oil deal in 2009, or Iran’s kidnapping three American hikers and accusing them of espionage two years ago. Here the point is to face down the West publicly, and generate popular support at home. The message is: Western actors are trying to sabotage the people of the Middle East, but the ruling authorities are proud heroes of resistance who have exposed the designs of the imperialist or Zionist oppressors and have made them publicly pay for their crimes.

The Egyptian army probably didn’t want to get into this game of political extortion, but with Mubarak’s downfall it became necessary to win the affections of a very demanding audience: Egypt’s middle-class urban youth, a constituency to whom Mubarak never paid much attention, which is precisely what led to his demise. The Obama Administration believed that Mubarak’s exit would have little effect on an Egyptian political system still dominated by an army dependent on $1.3 billion in American military aid each year, but the problem should now be as obvious to the White House as it was to the Egyptian military from the outset. As angry as the army was at Mubarak for trying to install his son in the presidential palace, it also understood it was dangerous to give the mob a de facto veto that would allow it to shape the Egyptian political system however it saw fit.

That vision, unfortunately, is very popular in the Muslim-majority Middle East. It’s generally anti-Israeli and anti-American, to be sure, but Israel and the United States are details in a larger architecture of resentment of the West.

Hatred of the West, and of its local proxies, has been a central part of political Islam’s program from the outset. The Muslim Brotherhood was formed in 1928 in the midst of Great Britain’s 72-year-old occupation of Egypt. But long before London took an active role in Egyptian politics, 18th- and 19th-century Muslim intellectuals and activists counseled the masses to be suspicious of the West. Take their science and technology, they advised, but forgo the West’s secular values, which undermine you and your faith.

Today, those who advocate for engagement with Islamists argue that groups like the Muslim Brotherhood and Tunisia’s Nahda Party have matured and are now willing to play by the rules and act like democrats. The Islamists may not like the West, but they have no choice but to uphold agreements and partake in the international system. On the other side of the debate, skeptics fear that the Islamists are talking out of both sides of their mouth, and once in office they’ll never willingly forsake power. But both of these arguments miss the point.

Yes, Islamism is already turning out to be the most powerful political current across the region. But the attraction of Islamism is not simply that it appeals to conservative and traditional Muslim societies, but that it draws freely on the sources of resentment that have been part of the political language of the region for more than two centuries. It was not Egypt’s Islamists who led the charge against the Israeli embassy in September, but young and nominally secular Egyptians. And it is that mob, potentially in the many millions, with whom Egypt’s ruling body was currying favor when it arrested Grapel.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).