The Arab World Needs a Leader in Egypt

What Egypt’s elections mean to the region

It’s been exactly seventeen months since the revolution that forced Hosni Mubarak’s ouster ignited in Cairo. And with the revolution came some understanding of just how far Egypt had tumbled into irrelevance. The Egyptian economy was stagnant, its unemployment rate was massive, its literacy rate was staggeringly low, and its poverty rate was unconscionably high. Enfeebled by autocratic rule and three decades of emergency law, political corruption was rampant. While its neighbor Sudan devolved into genocide-ridden conflict, Egypt stood idly by, without clout or influence. You get the picture.

Despite all its recent impotence, the symbolic vitality of Egypt cannot be understated. Egypt’s population is more than double that of any other Arab country. Once the center of the Arab world, its capital, Cairo, was a natural venue for President Obama to deliver his 2009 speech on the Middle East, a speech that was as aspirational as it was foreboding in light of what took place in the Arab Spring that followed.

There are countless reasons to brood about the results of Egypt’s first-ever free presidential election, which (eventually) awarded the premiership to Mohamed Morsi, a representative of the troubling and controversial Muslim Brotherhood. The election was sullied by boycotts and a thin margin of victory both of which preclude a popular mandate at a time when Egypt needs a clear vision for its future. Last week the generals of the Egyptian military (which dismissed the Brotherhood-led Parliament the week before) passed an interim constitution that enriched themselves with many of the powers originally meant for the president at a time when Egypt needs accountable leadership.

While Morsi has resigned from the Brotherhood and explicitly stated that he plans to maintain Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, respect the rights of women and minorities, and represent a set of interests broader than turning Egypt into a theocratic state, the challenges he faces in transitioning into governance are massive. The calculus is as complex as the pitfalls are plentiful. Morsi needs to be buoyed by the international community so he keeps to principles that will stabilize the region and lead Egypt out of its political morass.

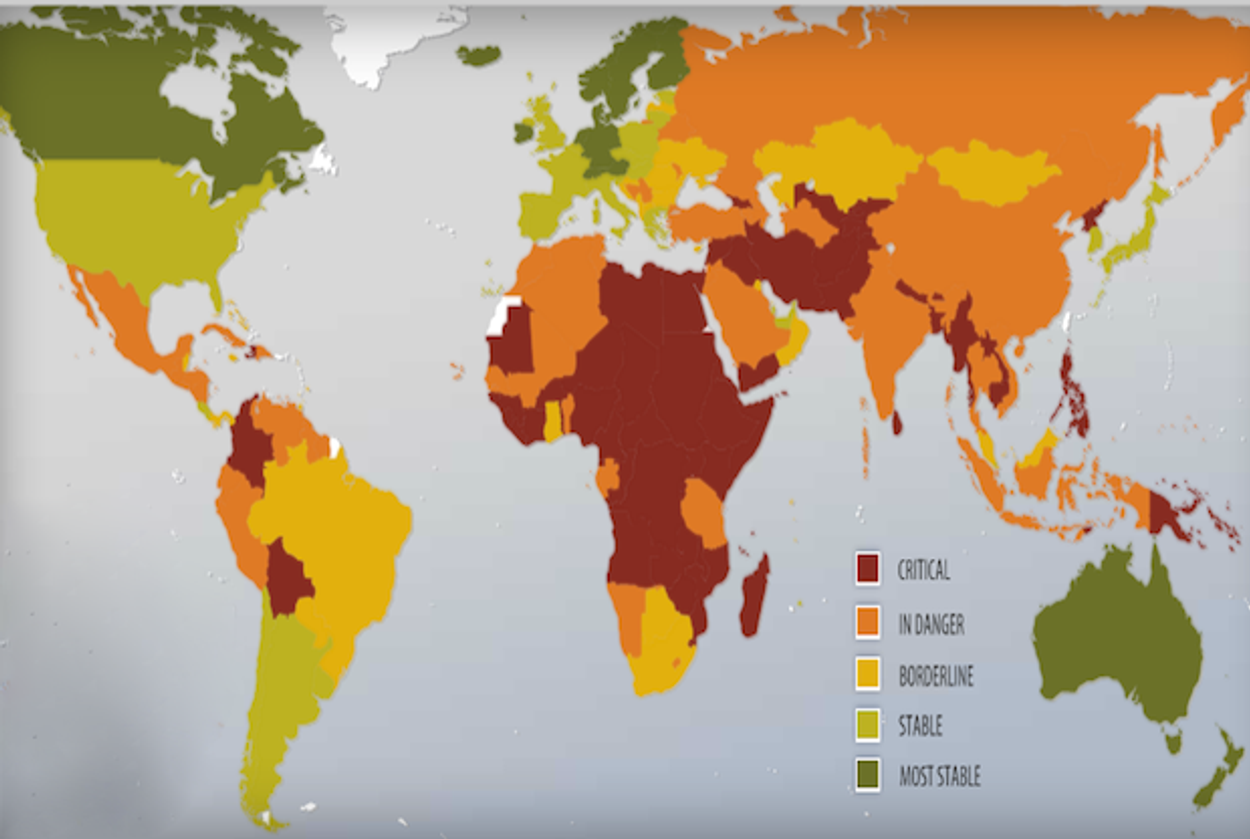

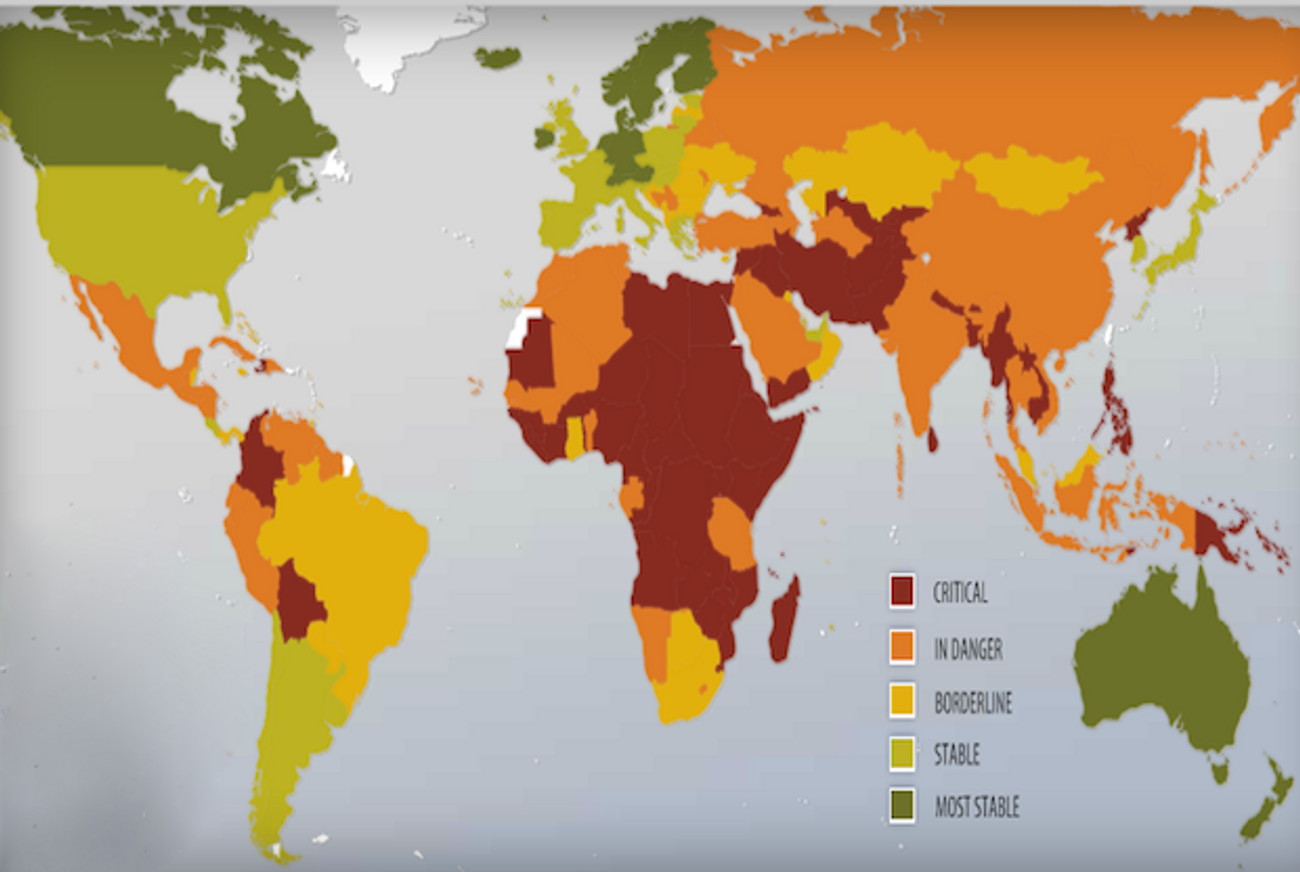

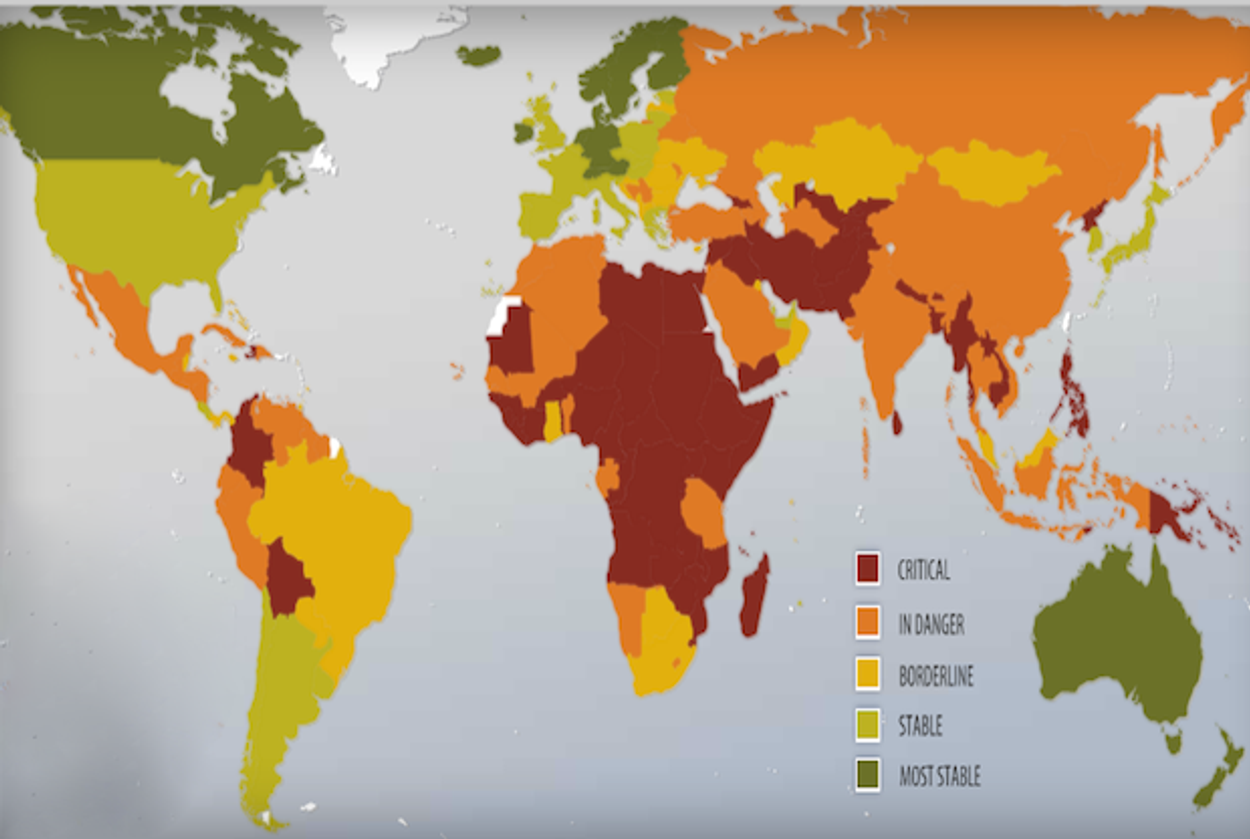

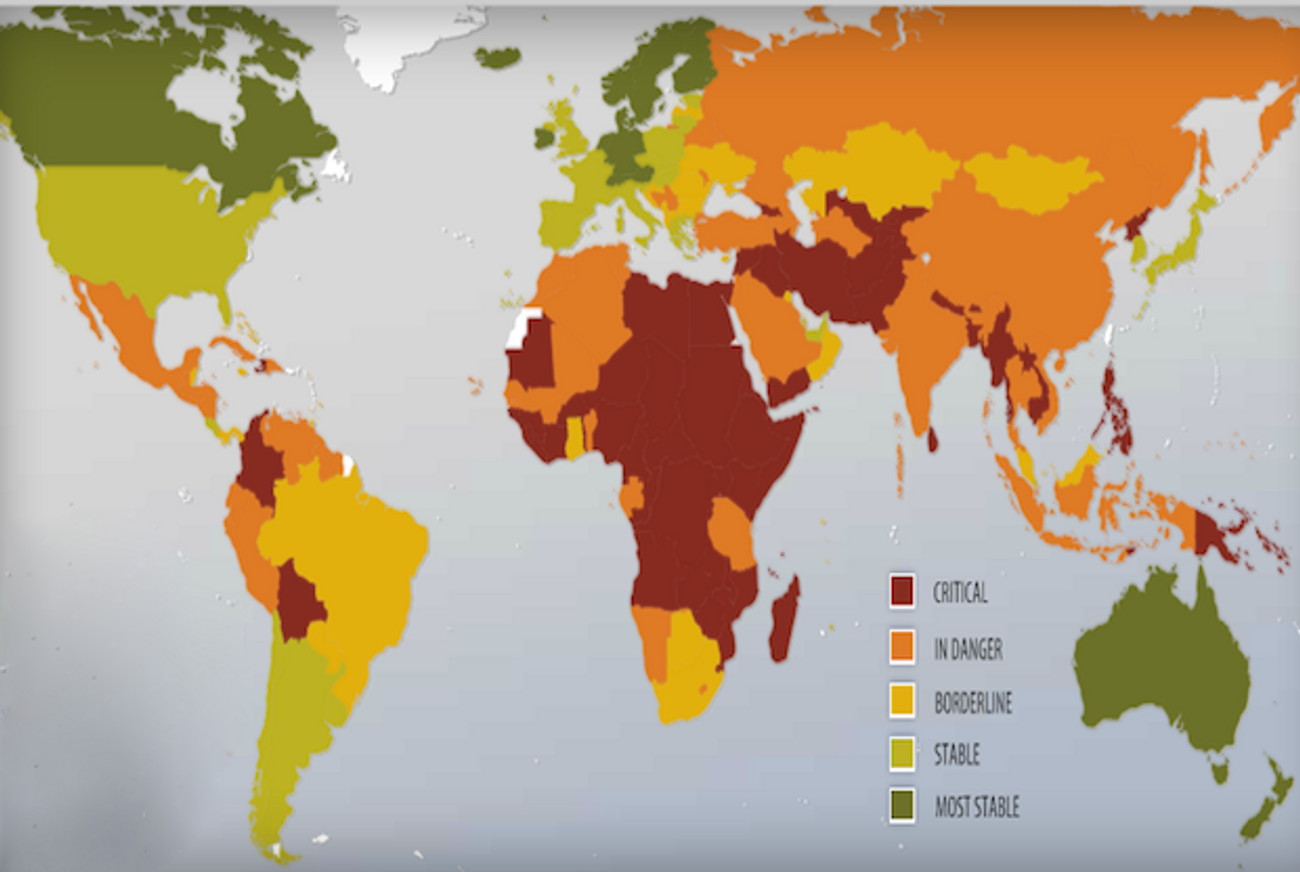

The stakes are immeasurably high. The Middle East now has a void where none of the regional powers—Israel, Turkey, and Iran—are Arab states. With so much left unwritten in the narratives taking shape across the Arab capitals, the success of a home-grown democracy as a viable paradigm of governance is paramount. Despite the misgivings many have about Morsi and the Brotherhood (and there are countless to be had), the world is wedded to this reality. Once again, Egypt is the lynchpin.

Earlier: Morsi Code: Egypt Goes to the Polls [The Scroll]

Challenges Multiply for Presidential Winner in Egypt [NY Times]

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.