Four Score and Philip Roth

A dispatch from the author’s 80th birthday

Growing old is easy. It’s staying old that is a mortal challenge.

For those who began reading Philip Roth as he began writing, with pawky provocations such as Goodbye, Columbus (1959), Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), and The Breast (1972), he remains the eternal enfant terrible of American letters. Yet Roth turned 80 on March 19, and Roth himself, as his friend Edna O’Brien stated publicly, “recently believed that the number 80 was a house number.” A full house at the Newark Museum marked the occasion in a style that recalled the banquet years in Paris, when the French used to feed their living lions with elaborate meals and extravagant praise. For two days, scholars, friends, and other curious people descended upon the author’s blighted native city to examine his legacy and wax Roth. When William Butler Yeats died, W. H. Auden observed that: “The words of a dead man/ Are modified in the guts of the living.” But Roth is still very much alive, and chewing over his written corpus can seem like gorging on a carcass that is not yet a cadaver.

Literary scholars have a habit of clustering in single-author societies, focusing their attentions on such canonical figures as Emily Dickinson, Henry James, Herman Melville, John Milton, and Edmund Spenser. There is even a Constance Fenimore Woolson Society, dedicated to the study of a 19th-century American novelist best known as a friend of James. Is the e.e. cummings Society chronically undercapitalized? Are those who join the Robert Frost Society rather than, say, the William Faulkner Society or the Cormac McCarthy Society haunted forever by the road not taken? Yes, there is a Philip Roth Society, founded in 2002, that publishes both a newsletter and the academic journal Philip Roth Studies. On March 18, Erev-Roth Day, it convened a day-long conference called Roth@80 at the Robert Treat Hotel, a 96-year old landmark named for Newark’s founder; Roth specialists would certainly recall fictional Robert Treat College, which Marcus Messner attends in Indignation (2008). Scholars from more than a dozen countries, some as far away as New Zealand, India, and Russia, delivered papers on the work and life of the birthday bokher. Topics covered included sex, humor, transgression, Jewishness, and death, as well as Roth’s affinities with Saul Bellow, J.M. Coetzee, Franz Kafka, Grace Paley, Henry Roth, and William Shakespeare.

That this scholarly organization is not necessarily an adoration society was apparent in several presentations that emphasized Roth’s obsession with controlling every detail of his reputation, from cover to dust-jacket, from advertising to translation. He has gone through editors and publishers the way Bellow went through wives. A member of the John Updike Society noted that organizing its conference a few years ago was much simpler, because its author was already dead. Not only did Roth insert himself into planning his birthday tribute, but he has exerted ventriloquial control over the biographical record. In 2004, denying anyone else encouragement and access, he anointed Ross Miller, a professor at the University of Connecticut, to be his authorized biographer. However, Roth later replaced Miller with Blake Bailey, the biographer of Richard Yates and John Cheever. Bailey was present for the birthday in Newark, but so were other would-be biographers who regard Roth’s blessing as both an advantage and a handicap. Ira Nadel, a professor at the University of British Columbia who has published biographies of Leonard Cohen and David Mamet, insisted that the cunning creator of treacherous characters including Nathan Zuckerman, David Kepesh, and “Philip Roth” is deliberately setting traps and false trails for those who would write about him. Nadel intends to steer his own way through Roth’s elusive life.

As befitted the setting of the conference and much of Roth’s fiction, the largest city in New Jersey formed the subject of several presentations. Mark Shechner, a professor at the University of Buffalo who was born in Newark seven years after Roth, described their antebellum neighborhood, Weequahic, as a shtetl and recalled how the gangsters were Jewish and Yiddish was the lingua franca. Michael Kimmage, who teaches history at Catholic University, emphasized how Roth is repeatedly writing about a vanished urban space—his Atlantis, his Troy, his Jerusalem, a coherent Jewish community that, after Newark became the poster child for urban decay, exists solely in nostalgic retrospect.

That realization did not prevent the Roth scholars from piling into three buses in order to tour “Roth’s Newark.” Conceived and operated by the Newark Preservation and Landmark Committee, the three-hour outing stopped at Stations of the Roth Cross—including his boyhood home at 81 Summit Avenue, the Newark Public Library (where Neil Klugman has a job in Goodbye, Columbus), and Weequahic High School (where, in American Pastoral (1997), Seymour “the Swede” Levov excels in three sports). At each stop, an appropriate passage was read aloud from one of the books. Portnoy’s Complaint provided the chant recited in front of Weequahic High: “Ikey, Mikey, Jake and Sam,/ We’re the boys who eat no ham, We play football, we play soccer—/ And we keep matzohs in our locker! / Aye, aye, aye, Weequahic High!” The camera-toting scholars (mostly white and Jewish) and current students of Weequahic High (African American) gazed at each other in mutual fascination. The curtains were drawn at Roth’s childhood home, a modest two-family building, but the current residents must be accustomed to the gaze of strangers, since it is visited occasionally by a Philip Roth tour, and a commemorative plaque has been affixed to the front. A nearby intersection has been renamed “Philip Roth Plaza.” It is not clear whether the police escort, lights flashing, that accompanied the visitors throughout their tour was a function of Newark’s crime rate or the esteem accorded literary scholars.

Among the 250 guests who gathered in the Billy Johnson Auditorium of the Newark Museum to honor the new octogenarian were some figures more famous than mere professors. Roth grew up rooting for the Brooklyn Dodgers and has Alexander Portnoy proclaim: “Oh, to be a center fielder, a center fielder—and nothing more.” So a baseball simile might score a run: The evening felt almost as if Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Duke Snider all showed up to toast Ted Williams. Seated in the audience were Paul Auster, Don DeLillo, Siri Hustvedt, and David Remnick. On stage, Jonathan Lethem paid tribute to Roth’s “torrential” voice. “The books are Jewish,” he claimed, “because they won’t shut up.” Crediting a reading of The Breast with jump-starting his own writing career, Lethem claimed that Roth “closed the distance between Bellow and Mad Magazine.” In clear Oxfordian cadences, Hermione Lee, a biographer of Virginia Woolf and Edith Wharton, stressed Shakespeare’s presence in Roth’s work. “There is something Shakespearean about the way he uses him,” she added. Claudia Roth Pierpont, a staff writer for The New Yorker, noted the presence of music in Roth’s fiction as well as the musicality of his prose but also, countering the canard that Roth is a misogynist, spoke affectionately about female characters of his who have seized hold of her imagination. She reported how once, after complaining to Roth that one was just too perfect, he replied: “You should hear what she says about you.”

Focusing on Roth’s final novel, Nemesis (2010), French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut described the author as a diagnostician of “the pathology of explanation.” His characters come undone when they refuse to accept life’s contingency and insist on finding logic where there is none. According to Finkielkraut, Bucky Cantor, the protagonist of Nemesis, “is a martyr of the why.” On a more personal note and with an Irish lilt, parrying persistent gossip that she and Roth were lovers, Edna O’Brien shared anecdotes from their enduring friendship. She offered no revelations about Roth’s two disastrous marriages or any other liaisons. O’Brien insisted that, as a writer, he is “like a trapeze artist,” and she praised his ebullience, precision, and gravity—his “artist’s dissection of the hemorrhaging of faith and hope.”

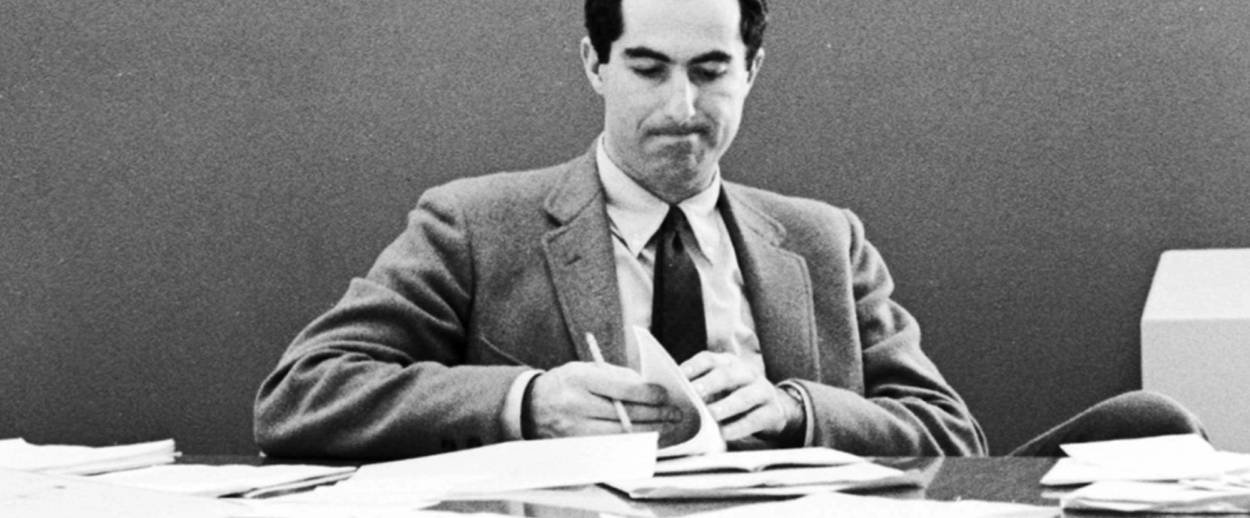

Then came forth Philip Roth, looking remarkably hale for 80 and all the rumors about ailments of the heart, the prostate, and the mind. Sitting at a table, his only concession to age and a bad back, he spoke deliberately and engagingly in the companionable voice that has drawn readers into 31 books and earned him enough literary prizes to shame the jurors in Stockholm. He praised Newark for shaping him and the realistic novel for its “passion for specificity,” its “ruthless intimacy.” Reaffirming his decision to retire from fiction, Roth teased the audience with a catalog of subjects he would no longer be turning words to get right. Then he proceeded to read seven pages from Sabbath’s Theater (1995), the book he called his favorite. The passage, an aging Mickey Sabbath’s thoughts while visiting the graves of his mother and father, is in itself a moving meditation on memory, love, and loss. The occasion made it much more poignant. Roth reminded us that the epigraph he had chosen for the novel, from The Tempest, is: “Every third thought shall be my grave.” Everyone in the audience, even those whose suspicion and cynicism had been finely tuned by the work of that most devious of novelists, knew that they had been present for an extraordinary moment in American literary history. His revels now ended, the Prospero of Weequahic exited the stage.

His revels now ended, the Prospero of Weequahic exited the stage.

In Exit Ghost (2007), the caretaker of Nathan Zuckerman’s Berkshire home and his wife prepare a private dinner for the reclusive author to celebrate his 70th birthday. When they ask Zuckerman what it is like to turn 70, he replies: “Think seriously about 4000. Imagine it. In all its dimensions, in all its aspects. The year 4000. Take your time. … That’s what it’s like to be seventy.” On March 19, 2013, none of the 250 guests at the Newark Museum asked Roth publicly what it’s like to be 80. But he might have replied: 5773—the current year in the Hebrew calendar. He has repeatedly insisted that there is no future to serious novels. At least for the passionate readers gathered at the Newark Museum, it will be hard to imagine a literary season without a new book by Roth, and harder still to imagine the extinction of literary fiction. However, as his 1960 essay “Writing American Fiction” complained: “the American writer in the middle of the 20th Century has his hands full in trying to understand, and then describe, and then make credible much of the American reality. It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents.” The second decade of the 21st century is no less exasperating, especially after one major American writer has relinquished the struggle.

Louise Erdrich has not yet given up on literary fiction, and, after Roth was escorted into the museum atrium by the Weequahic marching band, she delivered a benediction in Ojibwe. There was no bracha, but along with champagne and other pastries, hamantasch—unseasonal salute to the Jewish author’s roots—was served. Then the cake was cut—a monstrous confection in the shape of books whose icing spelled out titles from the birthday boy’s oeuvre. Philip Roth was gracious toward his well-wishers, but it was hard to read his smile as he slipped back out of Newark, retreating from the scene to let them eat cake.

Steven G. Kellman is the author of Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth and Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism.