The Man Behind Bob Dylan’s First Concert

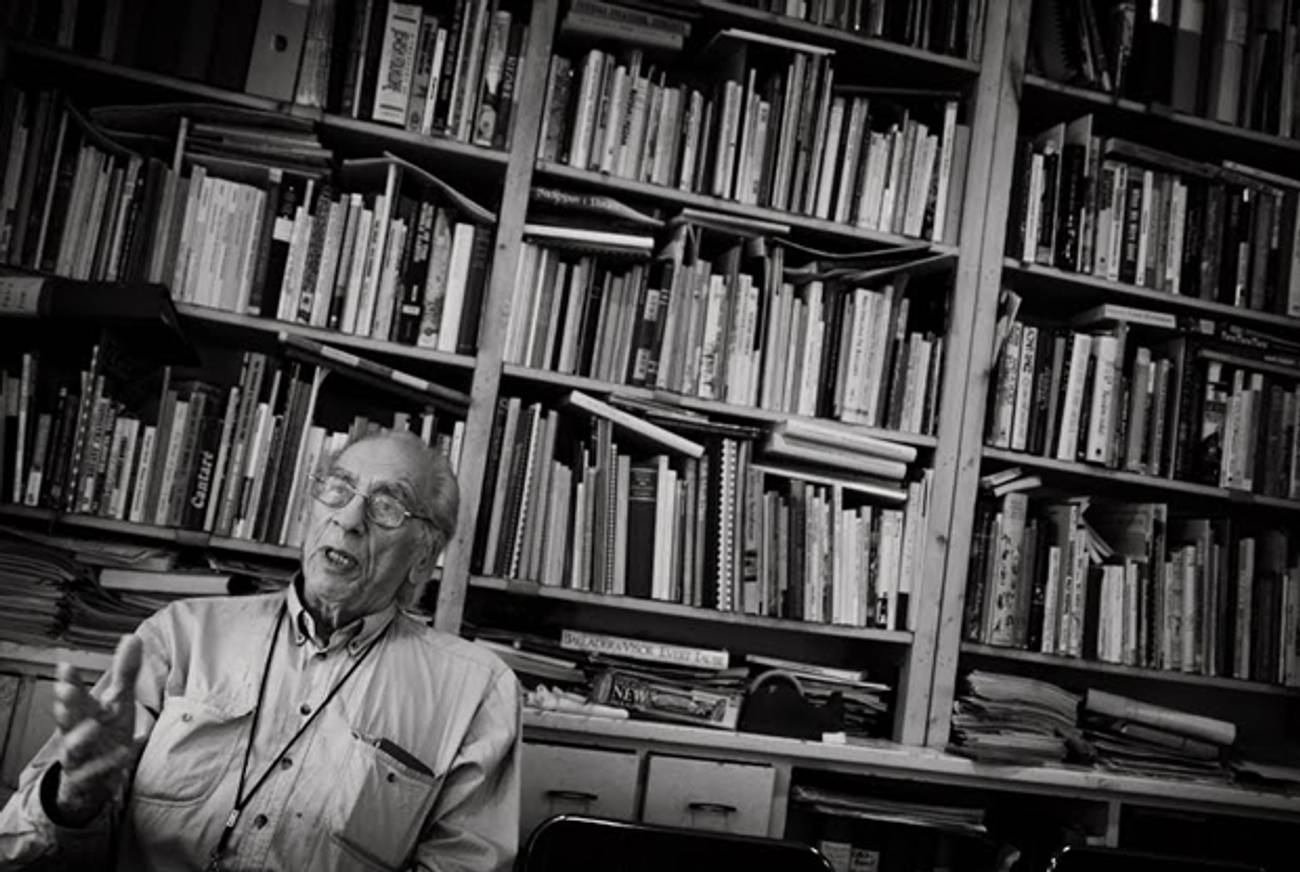

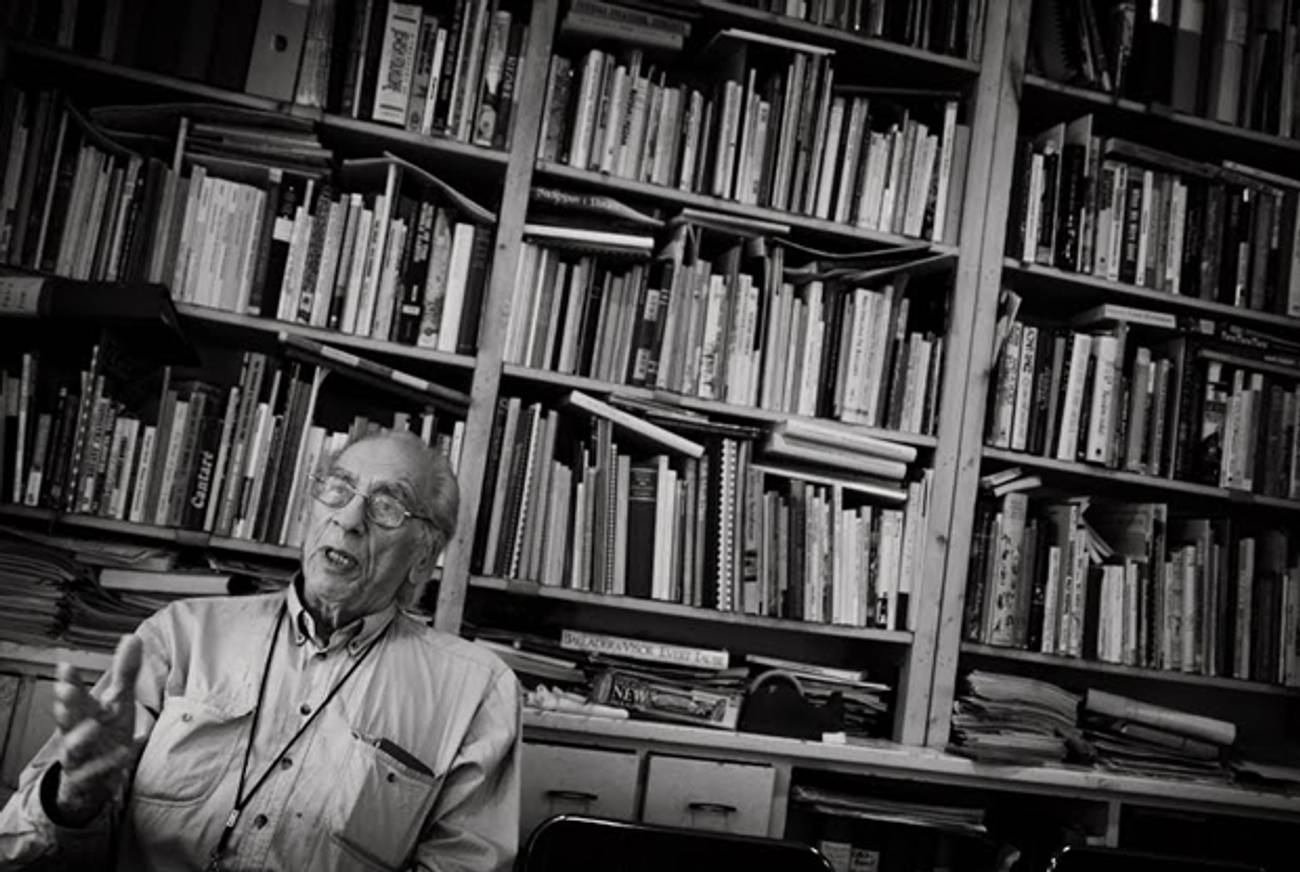

Israel ‘Izzy’ Young reinvents himself as the caretaker of folk music history

Look under the letter ‘Y’ in the index of any random book about Bob Dylan and you’re likely to come across the name Young, Israel. This Israel “Izzy” Young is credited with playing a crucial role in the rise of folk music in the 1960s, and with catapulting a young Bob Dylan to stardom by arranging his first proper concert, at Carnegie Chapter Hall, in 1961. Tickets cost $2.

Izzy Young’s Folklore Center on MacDougal Street in New York’s Greenwich Village was the epicenter of the folk music scene, a place of which Dylan once wrote: “What did the fly say to the flea? The Folklore Center is the place for me.”

Today, that quote is pinned to a noticeboard at the Folklore Centrum in Stockholm, Sweden, where Young has spent the past three decades arranging gigs for local musicians and collecting books and articles on folk music and the freewheelin’ days when beatniks and folkies flocked to the Village to reinvent themselves.

The mindset back then was to care less about where you came from than where you were heading. Much later, Dylan told a reporter inquiring about his myth-enshrouded past: “Nostalgia is death.” But nostalgia is what inspires Dylan fans to flock to Young’s Folklore Centrum in Stockholm even today. To them, Young, now in his 80s, is the guy who knew Bob Dylan.

“I get about three to six of them in here every week,” Young said of the Dylan fans. “They’ve read every single book there is about Dylan so why do they have to come here? Well, they want me to tell them stories about how Dylan fucked somebody here and took drugs there. They want sleaze … I’ve had up to 100 people like that in here this year and none of them have said anything interesting to me. That means they can’t get into him.”

With the passion and compulsiveness of a dedicated collector, Young has lined the walls of the Folklore Centrum with binders and scrapbooks filled with newspaper clippings, photos, and flyers. A whole bookshelf in the single-room storefront, located at the heart of the once-bohemian neighborhood of Södermalm, is crammed with binders containing articles about Dylan from the Swedish press.

But Young would much rather talk about himself than about Bob Dylan; after all, he sees his role in launching Dylan’s career as just one part of his life, and the only part people seem to care about. But then Young hasn’t exactly resisted his reputation either. He carefully cuts out any Dylan article he’s quoted in and sticks them in the binder where he keeps clippings about himself.

Young gets frustrated when he can’t find a booklet he wrote about growing up in the Bronx. His archiving system follows a logic that easily eludes visitors as well, it seems, as its inventor. He turns over piles of papers, shuffles notebooks around, and peers under heavy folders. “Let’s see, let’s see,” he said, having lost none of his New York accent. “Poetry, letters, articles about Young … No … Oh, here’s something I call ‘odd bits about music to be dealt with later.’”

Then: “Aha! This is from the Village in 1969. My friend, he had this store selling guitars and he got married in my apartment. If I was still in New York City I’d be a bishop by now.”

Young has given up looking for the Bronx booklet. He’s now focused on a typewritten wedding invitation, which lists as the officiator “Israel G. Young, Minister, Universal Life Church, Modesto, Calif.” The menu includes knishes from Yonah Shimmel’s, chopped chicken liver, bagels, and “various plates of desiderata.”

“Can you believe that? This is in the Village, where nobody wants to know they’re Jewish anymore,” he said. “You see, I’m true to my origins. I don’t make believe it didn’t happen.”

Young was born in the Lower East Side in 1928. “I grew up on 110 Ludlow Street,” he said. “You can write that down.” He dives into his notes and folders again and hands me a four-and-a-half page manuscript he wrote over the summer. Much of it is dedicated to his Jewish upbringing, first on the Lower East Side—with “lots of markets, more Jewish theaters than in all of NYC, lots of kids to play with, the occasional visits to local synagogues”—and then in the Bronx, where Young’s family moved after being offered six months’ free rent to help fill the neighborhood’s new tenement buildings.

Young’s time at the epicenter of the U.S. folk explosion gets just a paragraph in the manuscript: “Those were my fabulous years,” he said. “Don’t ask me how I survived because I’m still trying to figure it out.”

It was during those fabulous years that Young arranged Dylan’s first gig. “I broke my ass to get people to come,” he said. “Only 52 people showed up but about 300 people remember being there. Everyone wants to say they were there. You understand?”

Young seems to resent the Dylan fans who come by the Folklore Centrum just to catch a glimpse of him, as if he were a live specimen of Dylan history. He hints at feeling used, and says he’s weighed down by financial worries and can’t afford the Jewish community membership fee. “People come from all over the world to see this place. I should really charge them.”

The last time he saw Dylan, the man with whom his legacy is inextricably linked, was five years ago. Young was allowed backstage at a concert after Dylan’s chief safety manager (“Can you imagine that concept!”) came to the Folklore Centrum to “check him out.” The two men chatted briefly—“straight talk,” Young called it—but after a few minutes a woman on Dylan’s team came over with a sweater for him.

“And he has to turn around like this so she can put it on him,” said Young, mimicking the aging folk king’s movements. “In other words, it was time for me to go. It reminded me of the final scene of Strindberg’s play The Father, where the man turns around and the servant puts a white robe on him. You know, like he trusts the servant but not his own family. That’s a terrible thing for me to think, but I don’t let anything stop me from thinking.”

Young has been trying to arrange another meeting with Dylan, but all correspondence has to go through Dylan’s office. “Maybe the only thing I might tell him would be, ‘You know, you and me are the same person.’ And he’s gonna say, ‘What do you mean, Izzy?’ So I’ll say, ‘Well, you do what you want and you’ve continued with it all your life and you haven’t changed, and I do what I want and I haven’t changed. So if I’m at the bottom of the economy and you’re at the top of the economy, there’s still no difference between us.’ And he would agree with me.”

Related: Coen Bros. Torture Another Schlemiel While Imagining They Are Dylan’s True Heirs

Previous: 50 Years Later, Bob Dylan Gets a Music Video

Nathalie Rothschild is a writer based in Stockholm, Sweden.