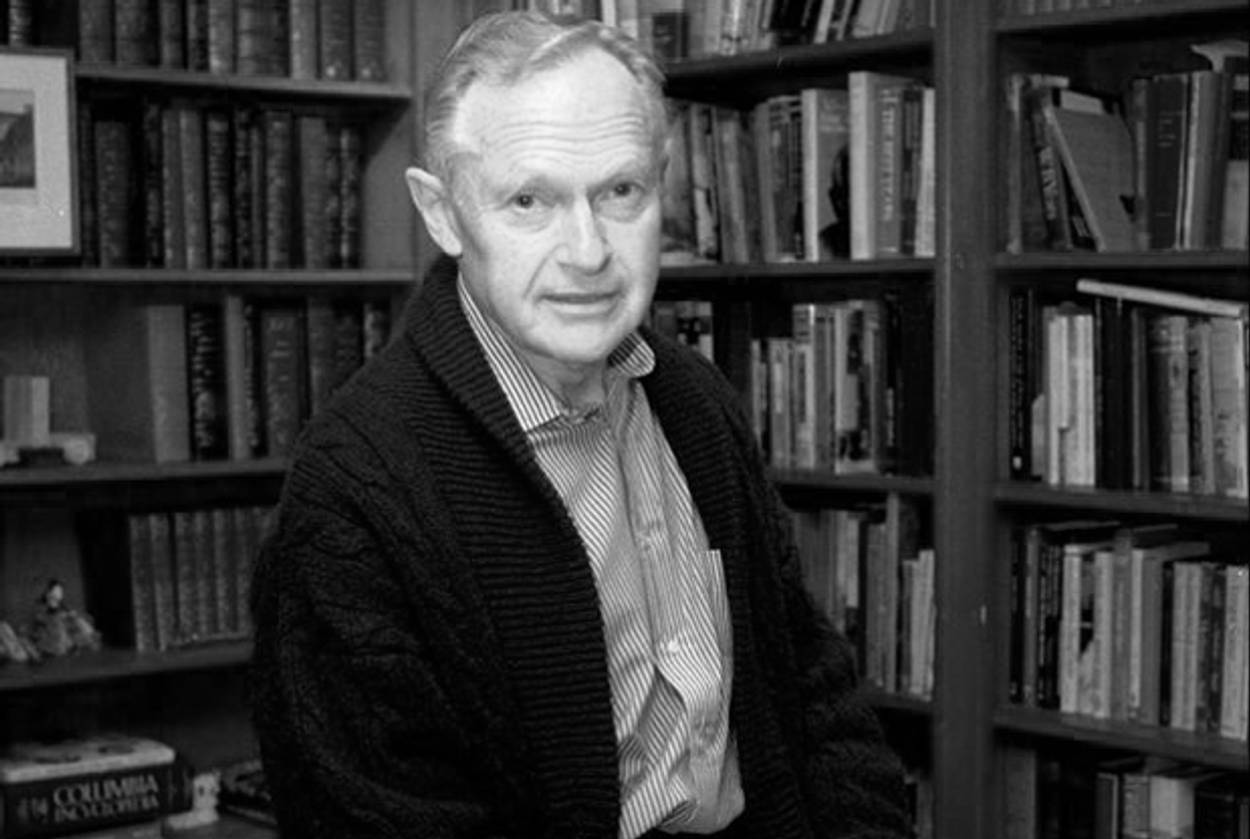

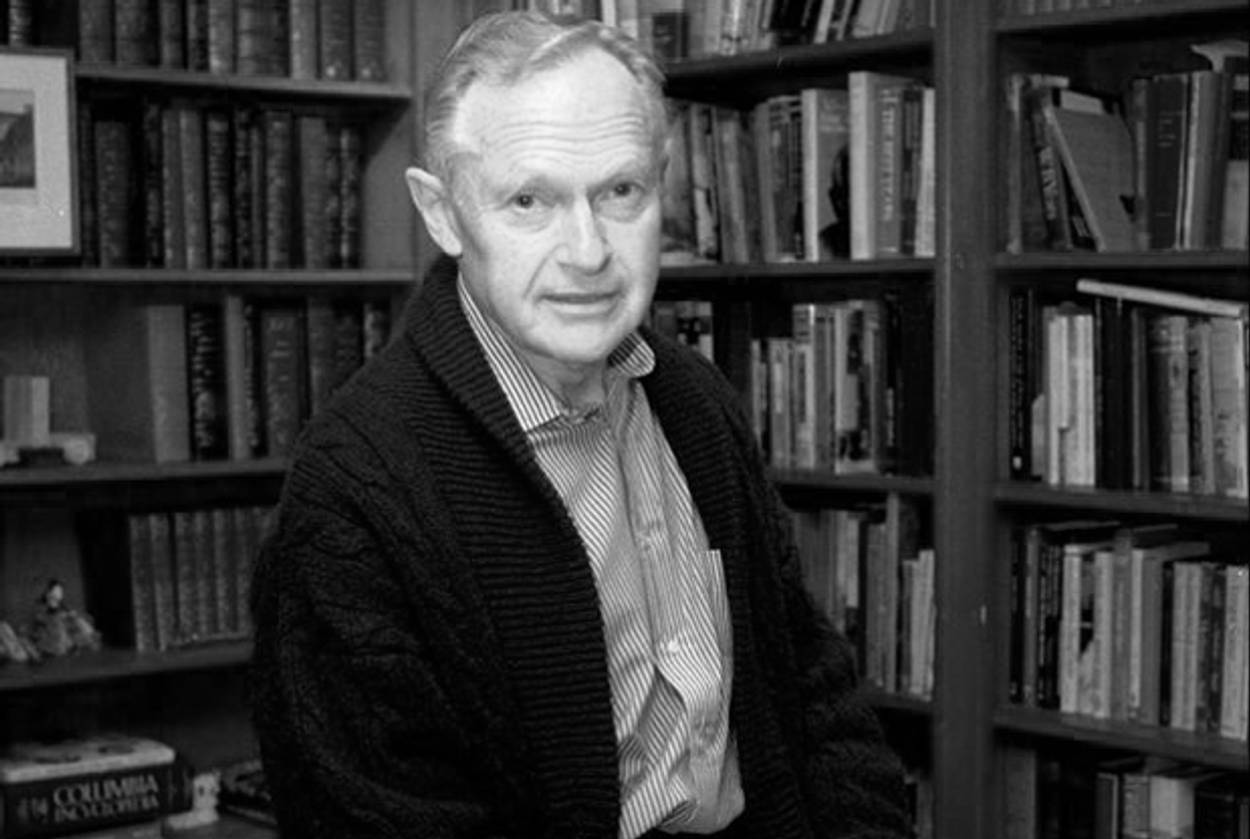

Reading Maimonides With Sherwin B. Nuland

The surgeon and writer, who died this month, tackled life’s tough questions

Sherwin B. Nuland, the surgeon and writer whose 1994 book, How We Die, won a National Book Award and changed the cultural conversation about end-of-life care, never shied away from life’s tough questions. When he died of prostate cancer earlier this month, an outpouring of obituaries and remembrances attempted to come to terms with the death of the man who told us so much, and in such exacting detail, about that very subject.

“Dr. Nuland wrote that his intention was to demythologize death, making it more familiar and therefore less frightening,” the New York Times wrote.

To Dr. Nuland, death was messy and frequently humiliating, and he believed that seeking the good death was pointless and an exercise in self-deception. He maintained that only an uncommon few, through a lucky confluence of circumstances, reached life’s end before the destructiveness of dying eroded their humanity.

“I have not seen much dignity in the process by which we die,” he wrote. “The quest to achieve true dignity fails when our bodies fail.”

Nuland, who was born Shepsel Ber Nudelman in 1930 in the Bronx, was the son of Orthodox emigres to the United States. He grew up with death as an ever-present reality: He was hospitalized at age 3 with diphtheria, his mother died of colon cancer when he was 11, and his father suffered from a debilitating chronic illness that Nuland would later discover, as a medical student, was the result of Syphilis. He was propelled towards medicine, most likely because of his early proximity to disease and death, and remained fascinated by the process by which humans reach the end of their lives.

Nuland’s interests vastly spanned the medical spectrum. He wrote an excellent book about Moses Maimonides—the 12th-century philosopher, medical sage, and prototypical Renaissance man—for the Nextbook Jewish Encounters series, which he modestly described as “this Jewish doctor’s study of the most extraordinary of Jewish doctors.” His was an impressive undertaking: how do you compile the work of a renowned scholar who himself compiled the work of those who came before him?

Sara Ivry spoke with Nuland in 2005, when Maimonides was published. In the interview, Nuland explained how Maimonides was, centuries before the Internet would be invented, the original aggregator:

He was essentially a compiler and a simplifier, and someone who made things accessible—like his crowning achievement in the Mishneh Torah. His books, they’re small volumes, very easy to understand, they can almost be memorized, because of course in those times people did memorize a lot of stuff. Unlike major figures like Avicenna and Rhazes who wrote long, complex, encyclopedic things, he simplified things so that every physician could easily understand it, and it was easy to find what you wanted.

Nuland too, throughout his own work, managed to deftly employ that very same ease of understanding. That’s what he aimed to do with his books about the study of medicine, and that’s how he helped to demystify the science of death. He was, in many ways, a modern-day Maimonides.

The New York Times ends Nuland’s obituary with a line from the last chapter of How We Die that is at once eerily prescient and peaceful: “The dignity we seek in dying must be found in the dignity with which we have lived our lives.” For Nuland, who lived a life full of inquiry, exploration, and yes, dignity, we can only hope that was achieved.

Related: The Good Doctor

Maimonides: Prologue

Stephanie Butnick is chief strategy officer of Tablet Magazine, co-founder of Tablet Studios, and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.