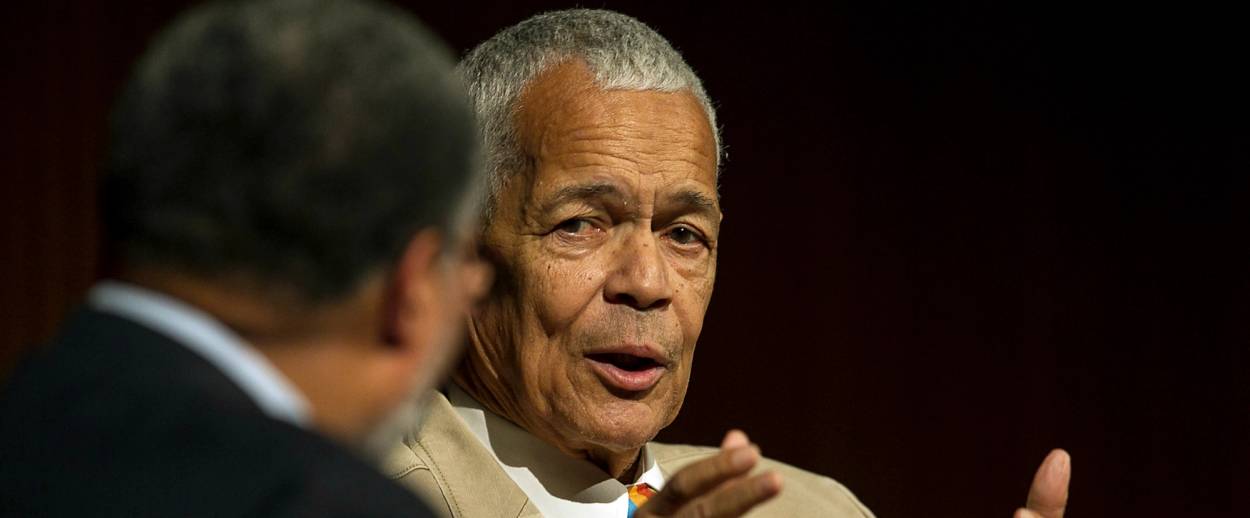

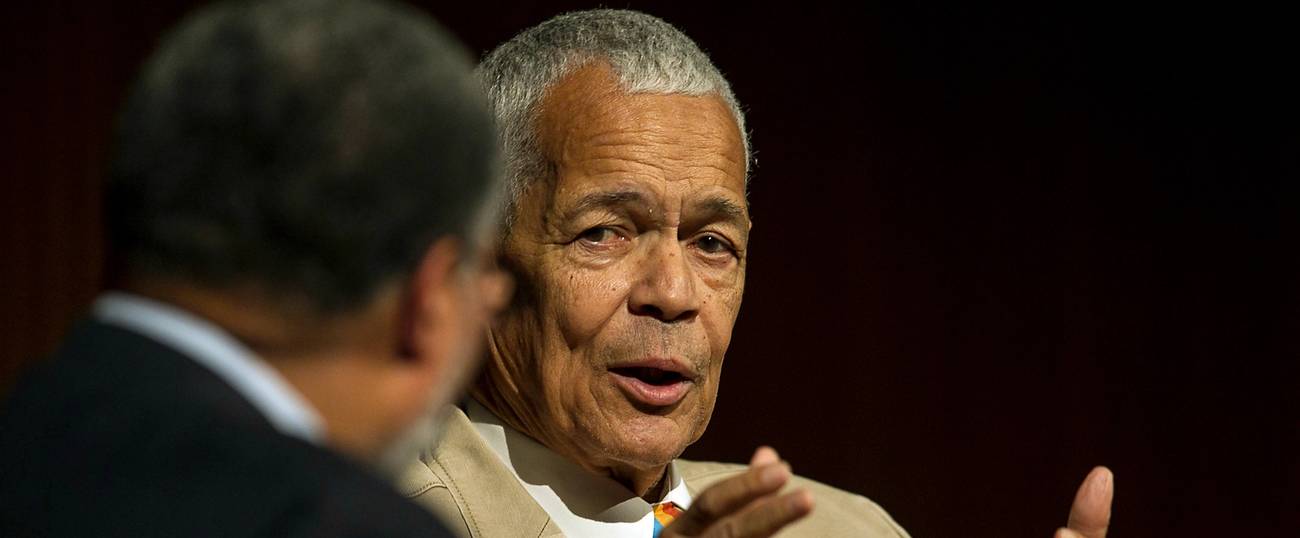

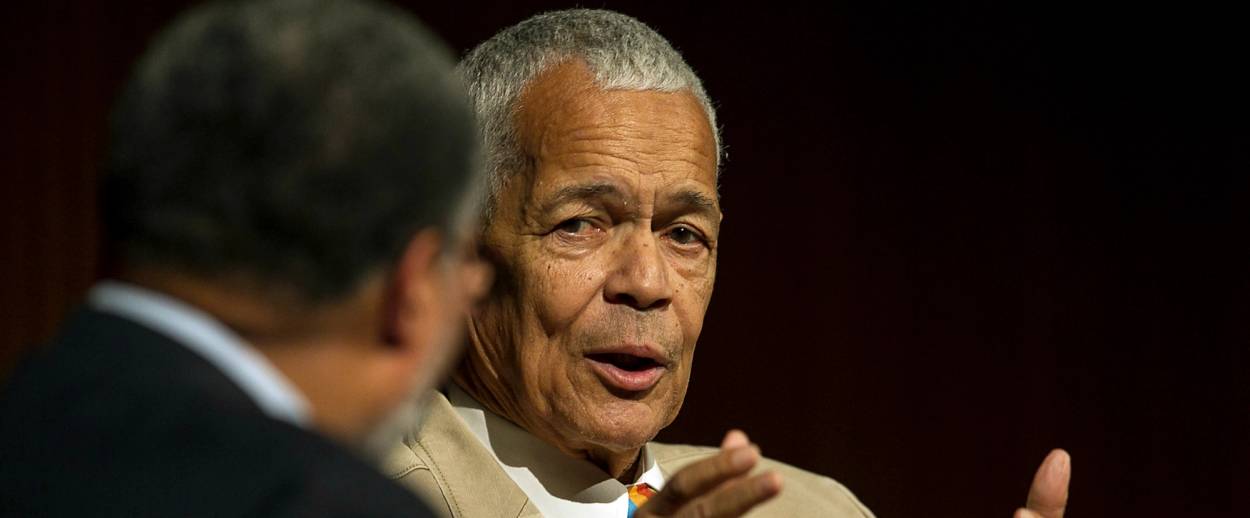

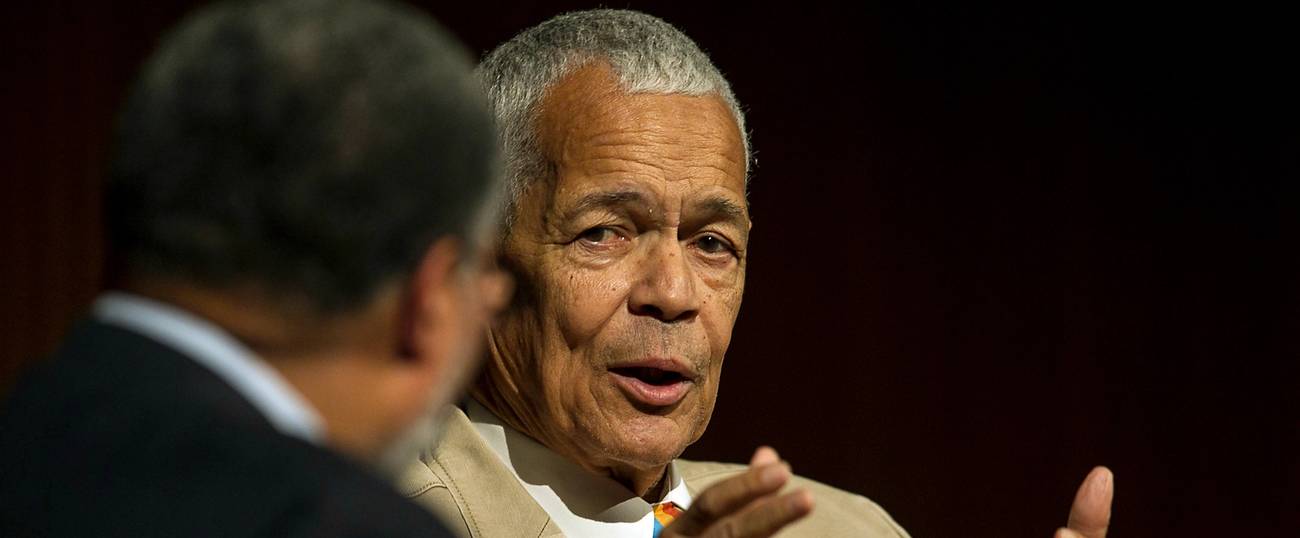

A Great Life That Matters

Julian Bond, a leader in the Civil Rights movement, former chair of the NAACP, professor, and pragmatic gentleman, dies at 75

Julian Bond was a gentleman. The son of a college president; the great-grandson of a slave; graduate of a Quaker prep school in Pennsylvania; Atlanta student leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the civilly disobedient shock troops of the civil rights movement, starting in its first year, 1960; college drop-out (he went back to Morehouse College years later and completed his degree); Georgia state representative and senator; chair of the NAACP and leader of its heroic efforts in behalf of black voters at a time when, as readers well know, it has been, and continues to be, rolled back by the political descendants of the white supremacists who disenfranchised them in the first place.

He was touched with nobility, movie-star handsome, an elegant dresser who complained about being photographed so often. Early in his career, he didn’t take to public speaking, though his sonorous baritone was indelible when he narrated the great documentary series Eyes on the Prize.

He was a pragmatist man of principle, no oxymoron intended. The principle was nonviolence, which, as one of his last public statements bears out—I shall quote it below—was his principle to the end. A pragmatist is not a trimmer. A pragmatist looks for results and changes his or her modus operandi—and theory—accordingly. Thus, at first, he and others in SNCC thought they were “still operating on the theory that there was a problem, you expose it to the world, the world says ‘How horrible!’ and moves to correct it.”

The world did not comply easily, evenly, smoothly, or fully. Ever. See above about the movement to roll back the African-American vote.

Starting in 1960, he was SNCC’s communications staff, working the phones and publishing a newsletter in Atlanta. In 1963-64 he was joined by Mary King. Organizational communications is today a cliché. But bear in mind that this was a time when, as King writes in her excellent memoir, Freedom Song, in most of the Southern press “black people were referred to disparagingly as ‘the Smith woman’ or ‘the Williams man.’ ” Most of the time neither the AP nor UPI would make any mention of the latest violence. Here is where Julian’s and my network of connections came into play. We would call our Friends of SNCC offices in northern cities and ask them to telephone the regional AP or UPI wire-service bureaus to inquire if the particular news item was being carried.

AT&T had just introduced a kind of telephone service called WATS, for Wide Area Telephone Service, for which unlimited long-distance calls could be made at a set monthly rate. King writes:

Julian and I set up a list of dummy surnames, using the names of trees, so that we could re-fuse to accept incoming collect phone calls with reversed charges, only to re-dial the call on the WATS line seconds later. A collect call from John Chestnut might mean that Atlanta should telephone Ruleville, Mississippi; a collect call from John Maple might mean that we should get back to the Greenville office; reversed charges from John Pine might mean that Julian or I should call McComb. We used this technique as long as we could until the local operators figured it out.

You could call Julian a natural aristocrat—in the original meaning, “best”—and that would be part of the truth. In public, at least, he was cool before cool was cool. John Schultz, the outstanding chronicler of the 1968 Democratic Convention protests in Chicago, caught him beautifully in 1969:

Bond has the air of a man who feels assured of his luck and of a destiny, a personal destiny inextricable from the movement of a social destiny. He is one of the few New Left leaders who does not act as if he is waiting for someone else. He is nobody’s right hand man. He does not cater emotionally to anyone, but he affects other people strongly. Bond supported [Senator Eugene] McCarthy [the antiwar candidate for the Democratic nomination], with no qualms about what his New Left brothers might feel, but when Bond was on the [speaking] stand with McCarthy, he was Julian Bond and that slightest touch of the usual subordinateness was absent. This was also true when he spoke to the demonstrators: he did not cater to them either, though all other speakers did. He received admiration cleanly, and exacted no price for it. He could walk among the demonstrators wearing an absolutely straight suit and wearing it well, and have their unreserved affection and admiration. He could walk in the Hilton and the same admiration was given, excepting the obvious racists.

Julian was the opposite of narrow. He was, in fact, precisely the sort of citizen whom Hamilton, Madison, and Jay envisioned as a leader of the Republic in their Federalist Papers, leave aside that in 1789 he would not have qualified to vote, let alone serve, in most of the United States of America. Thanks to the exemplary acts of citizenship pursued by the civil rights movement, it came to pass that in 1965, because of the Voting Rights Act, and against the skepticism of many in SNCC, he ran for an Atlanta seat in the Georgia House of Representatives. He ran a door-to-door campaign and found out that his constituents’ “problems were largely economic.”

When SNCC opposed the “aggressive” Vietnam war (“We believe that work in the civil rights movement and other human rights organizations is a valid alternative to the draft. We urge all Americans to seek this alternative … ”), the House voted 184-12 to unseat him. A few days later, and 15 months before his famous antiwar speech at Riverside Church in New York, Martin Luther King went to the pulpit at his father’s Atlanta church, called Julian Bond “a model of non-conformism,” and urged Americans to join him and SNCC in opposing the war. The Supreme Court subsequently—and unanimously—found that the House had deprived him of his constitutional rights and ordered him reinstated. He was elected to four additional terms, followed by four in the state Senate.

In 1968, Julian Bond led an alternative delegation to the Democratic Convention in Chicago and was nominated by the Wisconsin delegation for vice president. When Dan Rather, on the Convention floor, told him he “wasn’t likely to be a serious nominee,” since he was 28 and the Constitution had a rock-bottom requirement of 35 years, he quick-wittedly replied that, after all, “this convention might request that Congress change the age by election time.” His wit did not fail him in later years. In 2007, speaking to a Martin Luther King Day commemoration in Georgia, he said: “If you don’t like gay marriage, don’t get gay married.”

There is much to say about his following decades, during which he chaired the NAACP from 1998-2009, headed the Southern Poverty Law Center, and held a history professorship at the University of Virginia. But one particular episode in his later political life deserves to be far better known. It takes us into the 21st Century.

In July of 2000, under Bond’s leadership, the NAACP set up an activist arm to support African-American registration and voter turnout campaigns. Within four months, this National Voter Fund, also chaired by Bond, recruited a staff, trained them, and put them to work. “Florida was one of their priority states,” Heather Booth, who was hired as the National Voter Fund’s director, told me. Partly because of their efforts, the African-American vote nationally increased (from 1996) by 4 percentage points, while the voting rate for White non-Hispanics increased by 1 percentage point. In Florida, one of the Voter Fund’s priority states, the black share of the vote rose by one-third from 1996, from 10 to 15 percent. “This is the reason,” Booth told me, “that the Republican Party felt it needed to undermine the African-American vote in Florida, to push the election to the Supreme Court, and steal it.”

To my knowledge, Julian’s last public statement was this, sent on July 16, to Heather Booth, who is working on MoveOn’s campaign in favor of the Iran deal:

I have been involved in the struggle for justice and peace for more than a half century. In that time, I have seen issues which divided the nation along deep unbridgeable chasms and others that brought us together in the common pursuit of a shared vision for a better tomorrow. Today we have before us an issue that should unite all Americans, supporting the nuclear agreement with Iran. This historic diplomatic accord will not only help prevent the proliferation of mankind’s most heinous weapon, it will help avoid yet another disastrous war in the Middle East.

As Heather Booth says: “He made everything and everyone he touched better.”

Julian Bond’s family requests that contributions in his honor be made to the Julian Bond Professorship in Civil Rights and Social Justice at the University of Virginia.

Previous: The Black-Jewish Alliance

Related: In 1964, the Civil Rights Act Was Still a Dream. Then These Jewish Operatives Got to Work.

Todd Gitlin (1943-2022), was a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph.D. program in Communications at Columbia University, and the author of among other books The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street; and, with Liel Leibovitz, The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election.