How Social Psychology Explains the Erosion of the Bipartisan Pro-Israel Consensus in America

And why this trend is disastrous for pro-Israel policy

There is a prominent liberal meme concerning “yoostabees”: people who supposedly “used to be a Democrat” until 9/11 changed everything—including on issues wholly unrelated to 9/11. The joke usually takes the form of a mock declaration that “I used to consider myself a Democrat, but thanks to 9/11, I’m outraged by Chappaquiddick.” The idea is that while it is perfectly plausible that the September 11th attacks might change one’s views on foreign policy, there is no reason why it should affect beliefs about Ted Kennedy’s decades-past car crash—or any liberal domestic policy initiative like universal healthcare.

And yet, many of us have met such people, or their conservative counterparts—Republicans who turned into Democrats after souring on the Iraq war, for instance. This oddity is actually reflective of an interesting new branch of inquiry in social psychology known as “cultural cognition.” Cultural cognition suggests that most of us form our beliefs based not on reasoned and independent appraisal of evidence, but rather based on whether they align with our cultural predispositions and communities. In other words, most of our beliefs, most of the time, are mediated by the degree to which they are in harmony with our cultural priors. People prefer not to be outliers; they tend to decide ambiguous or contested arguments in a way that is consonant with the beliefs of their peers. This includes liberals and conservatives.

This phenomenon explains why the “since 9/11” crowd seemed to shift political positions not just on foreign policy but tout court. Their move from one cultural community to another altered which of their beliefs were in harmony with their new cultural cohorts and which ones were anomalous and needed to be jettisoned. More generally, cultural cognition explains why liberals tend to reject out-of-hand policy positions culturally coded as “conservative,” regardless of their merits, and why conservatives do the same to ideas viewed as “liberal.”

What does all this have to do with Israel? One of the great successes of the pro-Israel community has been its ability to keep “pro-Israel” a non-partisan issue. Unlike, say, debates over gun regulation, for most of the past few decades being pro-Israel has not been marked as a particularly liberal or conservative position. There was no oddity or strangeness to either a Democrat or a Republican considering themselves to be “pro-Israel.” This cultural neutrality is what allowed strong and stable bipartisan support for Israel to sustain itself.

But recently, the neutral cultural coding of “pro-Israel” has been threatened. Writing in Haaretz last week, Ari Shavit warns that “Netanyahu and his patron, Sheldon Adelson, have forged a dangerous link between Zionist issues and conservatism,” implanting in the cultural mind the idea that being pro-Israel marks one as a conservative. Yet where Shavit sees disaster, others see opportunity: the idea that “pro-Israel” is now solely consistent with a conservative worldview is openly trumpeted by Republican politicians and conservative activists alike. In Israel Hayom, Richard Baehr derides as “fake” the pro-Israel bona fides of the large majority of Democrats who support the Iran deal; Ted Cruz’s father went further to say that Jewish Democrats aren’t really Jewish at all; and Mike Huckabee trumped them all by accusing Democrats of leading the way to a new Holocaust. In linking “pro-Israel” and “conservative,” these right-wing activists are in an alliance with the global far-left which argues much the same thing. They, too, wish to deny space for such thing as a “liberal Zionist,” arguing that if you’re not BDS, you’re ZOA, or if you oppose the Iran deal you must be in the bag for Likud, and so on.

Many have viewed this movement as normal, if somewhat distasteful, political jockeying. That undersells the threat dramatically. If the campaign to recode the political meaning of “pro-Israel” succeeds, the consequences for the American pro-Israel consensus could be catastrophic. The cultural cognition approach explains why: to the extent “pro-Israel” is culturally understood to be a conservative position, the likely result is an utter collapse in support for Israel amongst liberals, akin to what has been witnessed in Europe.

Unfortunately, this effort is not an act of mindless self-destruction. Rather, it emerges from perverse and misaligned incentives between the “pro-Israel” community writ large and the American conservative movement. For the former, this trend is deeply dangerous, but for the latter, it is actually a rational political strategy.

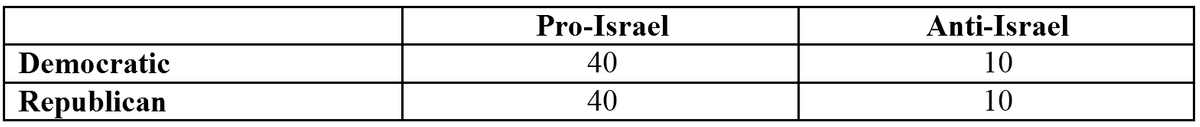

Here’s why. Imagine a simplified world consisting of 100 citizens, equally divided between Democrats and Republicans, most identifying as pro-Israel:

This is a stylized example of course, and flattens distinctions within the pro-Israel camp. But it is reflective of the recent status quo where both parties and America as a whole are strongly pro-Israel, with a relatively small dissident wing amongst the hard-left and paleo-conservative right.

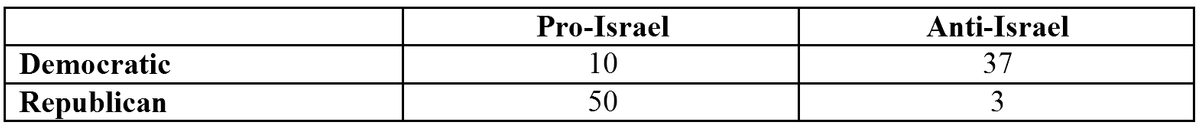

The cultural cognition model suggests this distribution is only stable insofar as “pro-Israel” is not culturally identified as being the province of one party. If that changes, and pro-Israel is rendered a Republican marker, two things are likely to happen: First, some number of Democrats—those for whom “pro-Israel” is an exceptionally salient position—are likely to defect to the Republican Party to maintain cultural harmony. And second, the portion of Democrats remaining pro-Israel is likely to implode; only the most committed stalwarts will be willing to go to bat for such a high-profile “conservative” position. (Similarly, the small contingent of anti-Israel Republicans is likely to shrink.) The resulting distribution would look something like this:

The precise numbers aren’t important. What matters is the broad outcome, which would be disastrous for the pro-Israel community: trading absolute aggregate- and party-level dominance for a much narrower overall majority and outright minority status in one of the two major parties. But it would be very good news for two groups: the anti-Israel community, whose support would double and would now be in control of a major political party, and Republican conservatives, whose relative vote share would increase (by 3%) and who have also become the dominant faction in the “pro-Israel” community (going from an even split with Democrats to a 5:1 advantage). From that outlook, the right/left alliance to promote the “pro-Israel = conservative” position makes perfect, terrible sense—and that very real incentive is precisely why it is such a genuine threat to the American pro-Israel consensus.

So, what can be done to combat this calamity, without compromising the content of the pro-Israel message? On Wednesday, I’ll explore several steps supporters of Israel should take to arrest this trend.

David Schraub is Lecturer in Law at the University of California-Berkeley. He blogs at The Debate Link and can be followed on Twitter @schraubd.