Fischermania

‘Pawn Sacrifice’ tells the story of the 1972 World Chess Championship in Iceland, a Cold War match between Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union and American Bobby Fischer

There’s a lot of ground to cover when it comes to Bobby Fischer. His life—at once fascinating, mysterious, and ugly—continues to be a draw. What if he’d continued to play chess deeper into his life? Could we then call him, without fail, the best to ever play? Why did Fischer renounce his Jewish heritage and grow so viciously hateful towards Jews, and the U.S. government?

It’s a narrative that continues to vex. There’s Bobby the child prodigy, who became the youngest U.S. chess champion in history after recording a perfect 11-0 record against his opponents, the formidable Samuel Reshefsky among them. Later in life, in the mid ’80s, Reshefsky visited the reclusive Fischer in Pasadena, California, for a few hours. When their conversation turned to Judaism, Fischer told him to go.

And there’s Bobby the first official American World Chess Champion, who took the title from Boris Spassky of the former Soviet Union in a weird and wonderful World Chess Championship match in Reykjavik, Iceland in 1972. Twenty years later Fischer was in desperate need of money, so he played Spassky again, this time in Yugoslavia, for a $3.5 million purse. In a letter, the U.S. government had told him not to, threatening arrest should he earn money there and try to come home. Fischer spat on it, never to return to the U.S. again except, perhaps, for his mother Regina’s funeral, entering via Vancouver, according to Frank Brady’s 2011 Fischer biography Endgame.

And then there’s Bobby the paranoid anti-Semite, who filled Filipino radio airwaves with anti-American bile after 9/11 (e.g. “It’s time for the fucking U.S. to get their heads kicked in”) and lived out the remainder of his life quietly in Iceland, the location of the acme of his chess-playing career, and where he was ultimately granted asylum. In 2013, I explored Fischer’s troubling legacy, particularly his anti-Semitism and apparent self hatred:

Jews, whom Fischer would also call “absolute pigs,” would become his default nomenclature for anyone who drew his ire, whether Chosen or not. He denied the Holocaust ever happened and believed that “hundreds of thousands of Jews should get executed in the U.S. … and go to some kind of concentration camp to be re-educated.” His anti-Semitism, which was at times conflated with his anti-Americanism, festered and was unleashed during sensitive times and continued in exile as he became enamored with The Protocols of the Elders of Zion; he was a tithing member of the Worldwide Church of God and later studied Catholicism, which he’d write “is just a Jewish hoax and one more Jewish tool for their conquest of the world,” before passing away on Jan. 17, 2008, in Iceland of kidney failure.

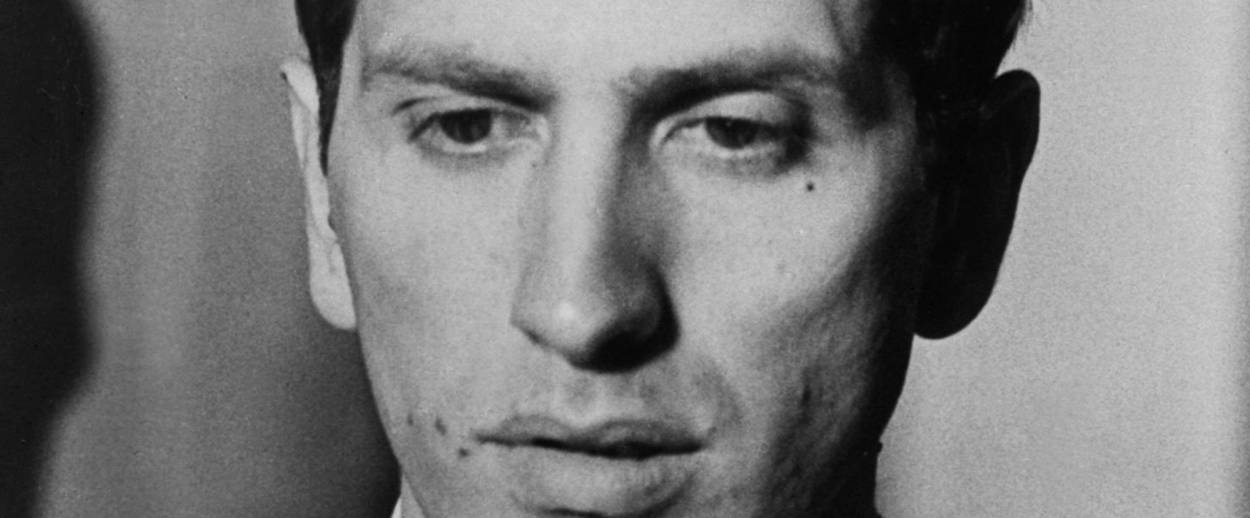

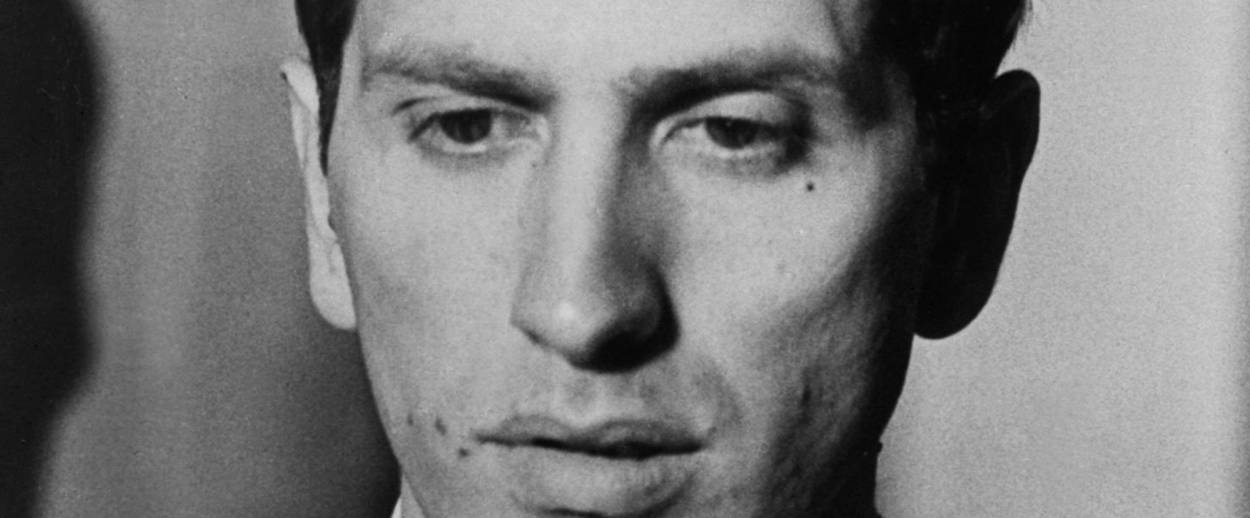

These are the broad strokes Tobey Maguire had to take on for his role as Bobby Fischer in Pawn Sacrifice, which opens to a wide release this weekend. The film, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last year, is directed by Edward Zwick (Glory, Blood Diamond, Defiance), and co-stars Liev Schreiber as Boris Spassky. I watched a screener of the film a couple of weeks ago.

As a chess fan, in the broadest sense, I’m delighted to see a movie about chess receive a top billing in theaters. The last time a film about Bobby Fischer made a splash was Liz Garbus’s excellent 2011 documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World. Other subjects, such as Garry Kasparov’s games versus IBM’s Deep Blue computer have enjoyed treatments, as well, along with Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess (2013), which is fantastic fiction. I imagine too that chess will continue to gain traction, both in film and in the general cultural zeitgeist, so long as that Norwegian-born assassin with a well-managed studnerd image—King Magnus Carlsen—continues to reign the international chess rankings. So, yes, please go see Pawn Sacrifice simply to support the chess arts.

The same goes for students of chess theory. The film is spot-on, complete with mentions of, say, the King’s Indian/Grünfeld, among other accurate representations of gameplay, including the first few games of Fischer’s best-of-12 championship match versus Spassky, which were played out move for move. (See, for instance, Fischer’s inexplicable and shocking bishop blunder in game 1, 29… Bxh2). It should be noted, however, that the film ceased to cover the 1972 World Chess Championship beyond game 6.

As a whole, however, Pawn Sacrifice felt too superficial in its exploration of a number of subjects, including the impetus for Fischer’s outspoken bigotry (we get some of Fischer listening intently to some tapped-out recording), as well as his other seemingly psychological ticks, such the infamous orange juicer he’d carry around so that he could see the juice being made in front of him. We do, however, get to see Maguire yell about “the Jews.”

Despite some choppy cinematography, the set designs and locations—it appeared that there were fill-ins for New York City’s Washington Square Park and the nearby Marshall Chess Club, where Fischer played perhaps his most legendary games—and costuming were great, down to Maguire’s every Fischeresque mole. In fact, the film mostly stays afloat due in large part to Maguire’s excellent acting—he worked Fischer’s brooding Brooklyn accent, lanky mannerisms, and kooky eyes to a T—but his chemistry with his counterparts, not to mention their own backstories, fell mostly flat if they were inflated at all.

Maguire’s co-star and rival, Liev Screiber, is the villain, which comes across as an age-old, half-hearted tinseltown crack at a Cold War narrative. The evil Soviet Empire is more or less represented through Spassky’s crew—he’s flanked by Commie-committed cronies in suits—and Spassky himself, who is portrayed by Schreiber as a chess sexpot, complete with Ray Bans and six-pack abs. (Notably, Schreiber speaks Russian in the film.) The same treatment is given to the political activities of Fischer’s mother, Regina, off whose Social Security checks Fischer lived later in life, which were exemplified by a folder that read “Suspected Communist Agent” in block lettering.

But perhaps my biggest qualm with this film, which I cannot deny, is what seems to be a judgment on the part of the filmmakers that the 1972 World Chess Championship is the most digestible, end-all Bobby Fischer narrative—because it is. The film is no more an exploration of Cold War politics (e.g. Henry Kissinger calls Fischer for inspiration) as it is an interpretation of Fischer’s anti-Semitism which drove his friends and family far, far away. That’s what I want to see, not the rise but the fall: Fischer the vagrant.

Rating: 2.5 out of 4 stars.

Previous: Current Movie Crush: ‘Pawn Sacrifice’

Related: Bobby Fischer vs. The Rebbe

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.