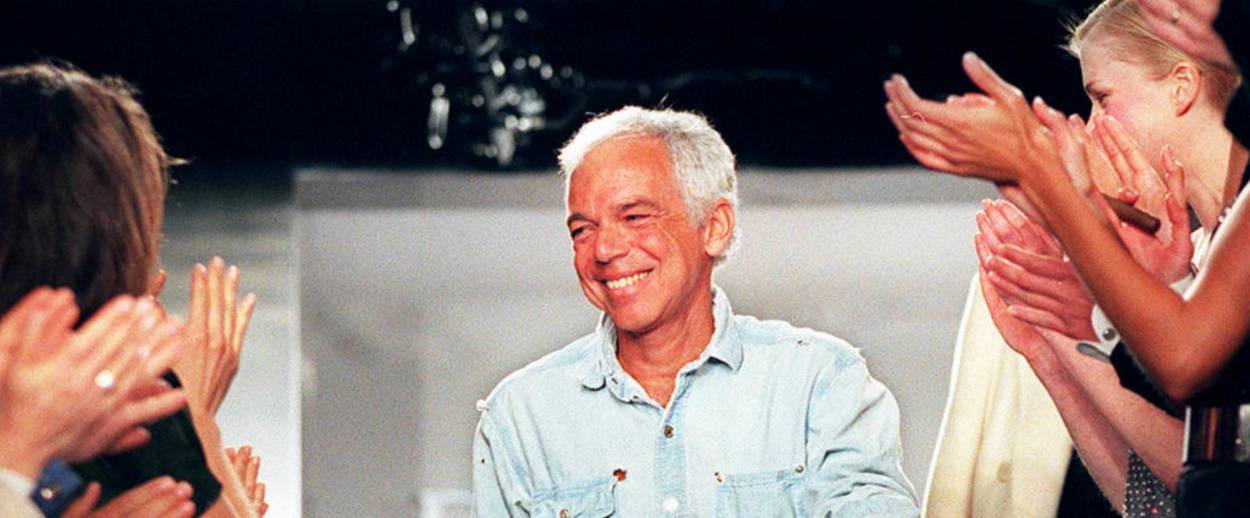

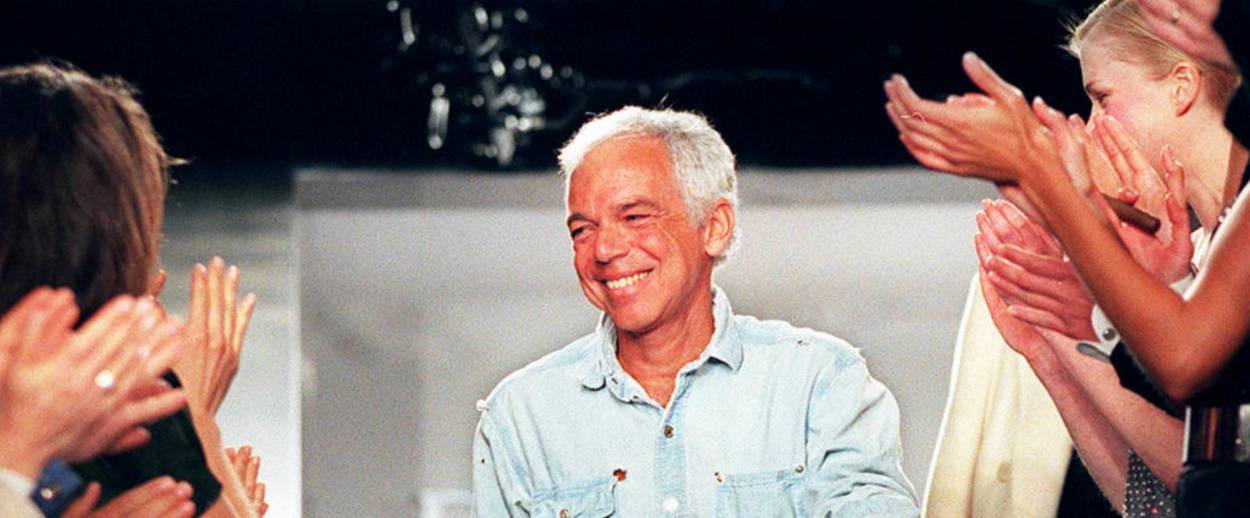

Fashion Genius

Ralph Lauren may be stepping down as CEO, but his polo shirts showed us how to play the part of a life well-lived, with money well-spent

Reading that Ralph Lauren was stepping down as head of the company he named after himself was, for me, a little bit like reading that a favorite baseball player I’d long since forgotten about was retiring. If you’d asked me if this childhood hero was still doing his thing, punching his time-card, I’d have said that, well, yes, I guess so. But the only Polo or Ralph Lauren items I own right now are deep-discount sheets from T.J. Maxx. No ponies in my stables these days.

I came of dressing-myself age in the early 1980s, when the Polo-insignia polo shirt was overtaking the Lacoste alligator polo-shirt as the pique status symbol of choice. I couldn’t tell you when I figured out that I wanted a drawer full of these shirts, but some triangulation among grade-school memories tells me that it must have been in in 1983 or so. I remember one tense conversation that summer with a counselor at the JCC day camp in Springfield, Massachusetts: he was old-school, favoring the alligator, and I was riding the pony. At first it seems impossible to think that my mother sprang for that overpriced shirt in several colors, but then I remember that when I was very young she enjoyed dressing me well (as I got older, and became less an extension of her, it became harder to wheedle big-ticket items). We must have bought the shirts at Blake’s, the proper middle-class, family-owned clothing story on Sumner Avenue. It’s gone now, of course.

My love for Ralph really effloresced when I was a bit older, ten or eleven, when he began buying those lush, multi-page advertising spreads that I saw in the front of The New York Times Magazine. Some weeks the Polo advertisement was only a page or two. But I tore into the Sunday Times every week with the hope that it would be one of the good weeks, with a multi-pager. Lauren knew what he was doing; he knew exactly what an aspiring kid in the provinces wanted to see, and that there must have been lots of us. These ads were whole cinemascopes of how the one percent lived, or at least how we wished they did, how we needed them to.

The photographs told stories, the models played characters. There was always a silver-haired paterfamilias, in ascot and even jodhpurs; his lockjawed wife, steely and well-coiffed, her posture and hair stiff with dignity in spite of her husband’s wandering eye; the cherry-cheeked daughters, just back from Wellesley and boarding school, wearing their field-hockey kilts while the maids did the wash they’d brought home; and their boyfriends and fiancées, ready to impress the future father-in-law with their skeet-shooting accuracy and low handicaps on the links.

I can think of two friendships from my adolescence that solidified on the foundation of a shared respect for what Ralph Lauren had done. Some children tried to figure out who to be by looking at sports stars, others by watching westerns or diving into science-fiction novels. But my friends and I wanted what Ralph Lauren showed us: a life lived with money, well-spent.

So what if it was all a fiction? Advertising is. Fashion is. Lauren was a schmatte guy born Lifshitz, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he couldn’t ride a horse, the big ranch in Colorado notwithstanding. But when he arrived in the big leagues, he came to play. Lauren isn’t the only Jewish outsider to help make the American prep style—cf. Jacobi Press of the J. Press company—but he’s the only one to take his act so far. He took it on the road and lived it. He put himself in his ads. He took his family along for the trot. (Even Lauren’s niece somehow ended up with his fake-Wasp last name.)

Lauren is, let’s be clear, a genius. He knew that Old Money was a hollow shell, as fictional as fashion, and therefore could be aped without consequence. And within a decade or two, the real Wasps didn’t know any better than to dress in his riffs on their vapid lives; their lives became, in fact, knockoffs of the ones his models were performing. There is no longer any way to have a big estate and play croquet on its lawns without referencing Ralph Lauren’s imaginary world. We’re all auditioning for his parts, and if we’re lucky, and have some bucks, we can cast ourselves.

Does Lauren’s successor, a Swede who apparently saved Old Navy, understand the great democratization that Lifshitz wrought? I doubt it. But his work is done. He changed the world, and it’s time for him to don his wide-wale cords and ride off into the sunset, atop his pony of many colors.

Previous: Bride of Ralph’s Son to Be Lauren Lauren

Who Is the Most Jewish Designer?

Related: Remembering Arnold Scaasi, Jewish Designer to the Stars

Mark Oppenheimer is a Senior Editor at Tablet. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox. He has contributed to Slate and Mother Jones, among many other publications. He is the author, most recently, of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood. He will be hosting a discussion forum about this article on his newsletter, where you can subscribe for free and submit comments.