Who We Lost in 2015

Remembering ‘The Simpsons’ co-creator Sam Simon, Living Theater co-creator Judith Malina, Amazon.com’s most prolific book reviewer Harriet Klausner, and many more

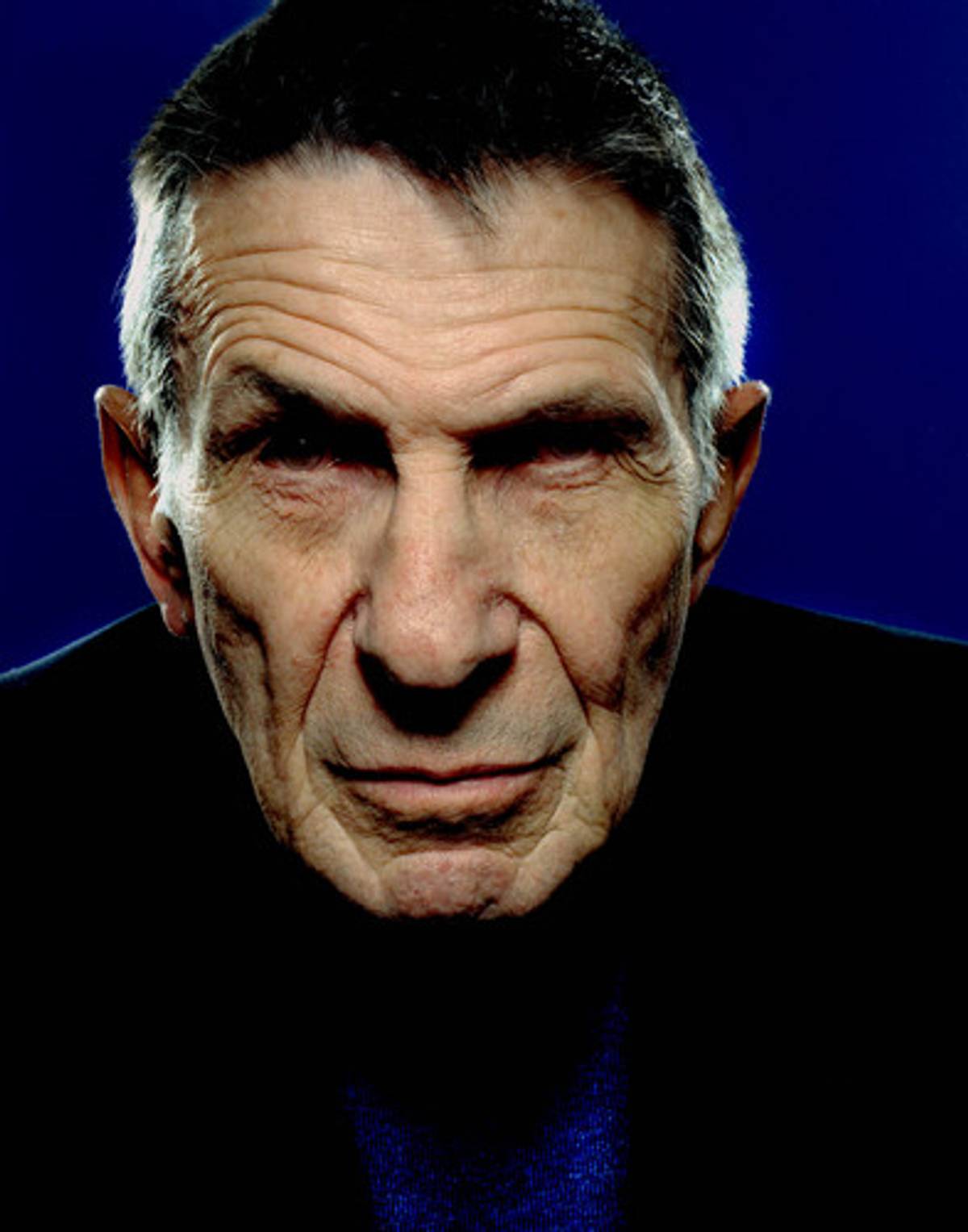

Over the last year, we’ve have taken note of some of this year’s losses. Among them are actor Leonard Nimoy, performance artist Rachel Rosenthal, neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, fashion designer Arnold Scaasi, scholar and visual artist Svetlana Boym, and musician Yosi Piamenta. But there are so many more—less heralded Jewish contributors to art, culture and science who also went to their eternal rest this year—to whom I want to pay tribute. May their memories be a blessing.

Attorney and civil rights activist Faith Seidenberg was most famous for forcing America’s oldest continually operating bar—McSorley’s Old Ale House in Manhattan’s East Village—to let women inside. During the summer of 1970, Seidenberg and a co-worker pushed their way into the all-bro-clubhouse and were refused service. They sued…and changed American law. Today, public places are no longer allowed to discriminate on the basis of gender. But Seidenberg fought other groundbreaking battles too: She determined that minors should be allowed representation when they appeared in court, defended civil rights workers involved in voter registration drives in the South, and won a landmark Title IX sex discrimination case involving the Colgate’s women’s ice hockey team. (She died on January 16, at 91.)

Poet Philip Levine was a working-class guy, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants who began toiling in Detroit’s auto factories when he was 14. He wrote beautiful poems about everyday life and hard work and industrial poverty, and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, two National Book Awards for Poetry and two Guggenheim grants. A snippet from his poem “A Sleepless Night”:

April, and the last of the plum blossoms

scatters on the black grass

before dawn. The sycamore, the lime,

the struck pine inhale

the first pale hints of sky.

An iron day,

I think, yet it will come

dazzling, the light

rise from the belly of leaves and pour

burning from the cups

of poppies.

Read more of Philip Levine’s work here. (He died on February 14, at 77.)

Yiddish linguist Joshua Fishman wrote over 80 books and over a thousand articles. A sociologist as well as a linguist, he was a man of many intellectual passions, exploring multilingualism, language revival, minority languages, the role of language in nationalism, and how language affects identity. He founded an academic journal, The International Journal of the Sociology of Language, and traveled around the world in a quest to nurture and preserve endangered languages. Wrote a colleague, “[Fishman] will be remembered by the Māoris of New Zealand, the Catalans and Basques of Spain, the Navajo and other Native Americans, the speakers of Quechua and Aymara in South America, and many other minority language groups for his warmth and encouragement.” (He died on March 1, at 87.)

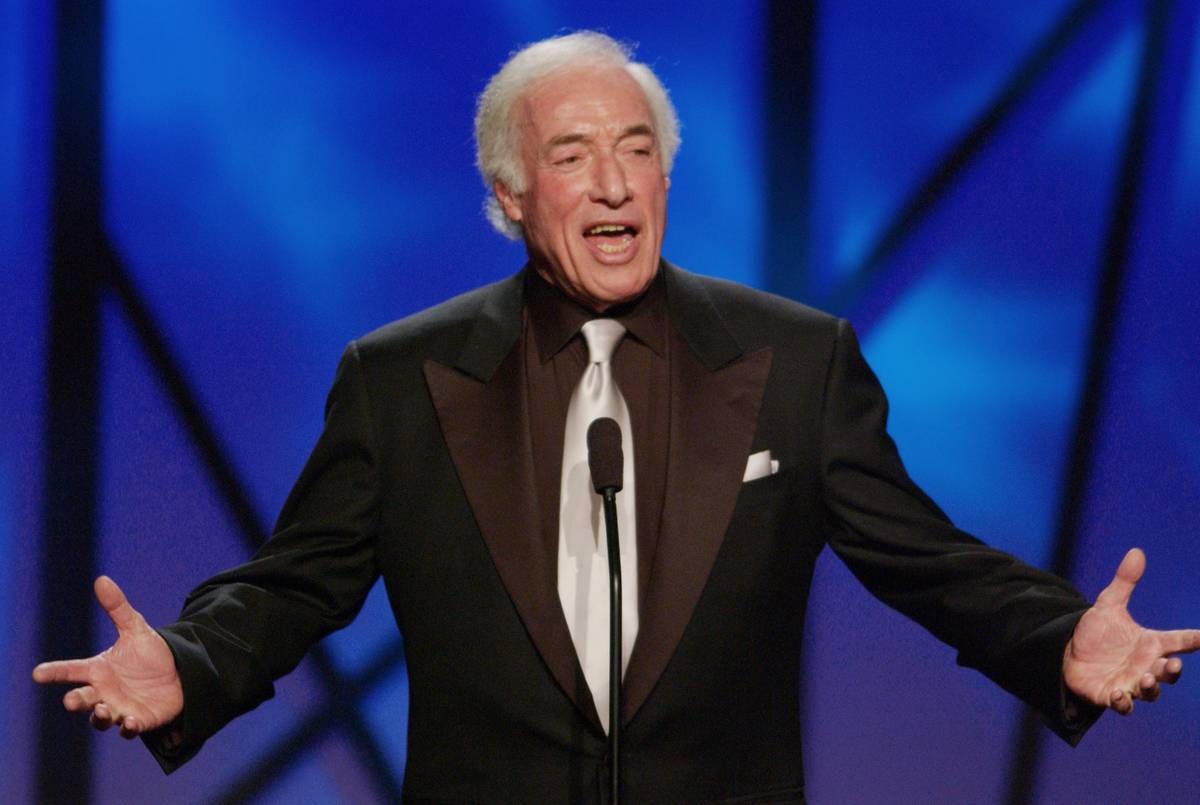

Co-creator of The Simpsons Sam Simon (who also served as co-showrunner, character designer, creative consultant, creative supervisor, developer, and writer of a dozen episodes) was heralded as “the real creative force” behind the show. (Since not all the show’s staffers have gotten along well with co-creator Matt Groening, Simon’s achievements—frequently involving brainy, literary humor—often slid under the radar.) Simon grew up in Los Angeles, across the street from Groucho Marx’s house, and attended Stanford University before becoming a TV writer on shows like Taxi and Cheers. When he was told he had colon cancer and had six months to live, he focused on giving away his entire $100 million dollar estate. An animal lover, he funded dog rescue organizations and animal surgery clinics for people who couldn’t afford medical attention for their pets, bought zoos and circuses to free the animals, donated funds to an anti-whale-hunting organization, and started a program to provide vegan meals for low-income families. (“They can eat all the meat they want,” Simon told The New York Times. “I’m just not going to pay for it.”) (He died on March 8, at 59.)

Gene Saks, former husband of Bea Arthur, was a theater director nominated for seven Tony Awards. He won three, including two for Neil Simon’s ultra-Jewish coming-of-age stories Brighton Beach Memoirs and Biloxi Blues. Saks directed Angela Lansbury in Mame, Alan Alda in Jake’s Women, Matthew Broderick in Biloxi Blues, the young Jane Fonda and Robert Redford in the film version of Barefoot in the Park, and Goldie Hawn in her Oscar-winning turn in Cactus Flower. Saks had a preternatural ability to nail perfect pacing, timing and line readings. “He could direct actors to be funny, but he wasn’t funny,” producer Emanuel Azenberg said. “He would say, ‘This is funny,’ in a very serious way. And you’d laugh, because that was funny.” (He died on March 28, at 93.)

Judith Malina co-founded the radical political theater group the Living Theater. Her shows were frequently fierce and loony, often breaking the fourth wall; cast and audience members sometimes stripped named. (Modern-day audiences, on the other hand, may remember her best as “Aunt Dottie,” the dying nun on The Sopranos who turns out to be Paulie Walnuts’s birth mother.) The German-born daughter of an actress and a rabbi, Malina believed that theater could foment revolution. In a 1968 New York Times interview, she said, “We can have tractors and food and joy. I demand it now!” A few months before she died, Malina hosted a Passover seder at the Lillian Booth Actors’ Home in New Jersey, where she’d moved in her later years. She used a customized Haggadah filled with explicit political parallels and quotations from Allen Ginsberg. (She died on April 10, at 88.)

Miriam Schapiro was a Jewish feminist artist whose work we’ve covered at Tablet. The co-founder (with Judy Chicago) of the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, she blended fine art and craft, incorporating traditionally “feminine” fabric treatments— sewing, piecing, quilting, hooking, appliqueing—into bold fine art works. (I first learned about her while writing a pretentious thesis about quilting as a metaphor for women’s writing.) A scholar of art history—and a Guggenheim Fellowship winner—she used photographic reproductions of Mary Cassatt’s and Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings in her collage work and painted portraits of Frida Kahlo atop her own self-portraits. (She died on June 20, at 91.)

Jerry Weintraub was the quintessential Hollywood macher who literally worked his way up from the mailroom. That mailroom was at the agency MCA, but by the time of his death he’d executive-produced a plethora of movie hits: Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975), Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982), The Karate Kid (1984), and (after a fallow period) the blockbuster 2001 remake of Ocean’s Eleven that grossed $451 million worldwide. Toward the end of his life he produced Behind the Candelabra, HBO’s Liberace biopic starring Matt Damon’s spray-tanned abs and also Michael Douglas. Second acts, baby. (He died on July 6, at 77.)

Jakob Bekenstein was a theoretical physicist who beefed with Stephen Hawking. The two disagreed about a characteristic of black holes, and ultimately Bekenstein triumphed. As a grad student at Princeton in the 1970s, the Mexican-born Bekenstein (the son of a carpenter and a homemaker, refugees who’d fled Poland during World War II) feuded with Hawking about space-time and entropy. (Bekenstein was able to visualize the loss of heat and entropy by pondering what would happen if you poured a teacup of hot tea into a black hole, which seems like a very Jewish thing to visualize.) Hawking finally accepted Bekenstein’s theory, and today the radiation from a black hole is called Bekenstein-Hawking radiation. Unlike some scientists, Bekenstein never saw religion and science as incompatible. “I look at the world as a product of God,” he told Haaretz. “He set very specific rules and we delight in discovering them through scientific work, to see how everything fits together.” (He died on August 16, at 68.)

Bud Yorkin should be the patron saint of all of us who grew up on 1970s television. (Good television, not crappy stuff like The Love Boat.) Interested in exploring race and class, he collaborated with Norman Lear on shows like Maude (featuring Bea Arthur as the first character on TV to get an abortion, at age 47, a year before the passage of Roe v. Wade), All in the Family, Sanford and Son, Good Times and The Jeffersons. He also executive-produced the movie Blade Runner. All these moments will be lost in time like tears in rain. (He died on August 18, at 89.)

Larry Rosen was “one of the most influential and tech-savvy modern jazz producers,” according to Billboard. He co-founded GRP records with piano legend Dave Grusin and won 33 Grammys. But what was noteworthy about Rosen was his lack of fear about the digital future; unlike many backward-looking record execs, he embraced technology. GRP was the first record label to issue every album on CD, back when CDs were scary and new. And it was the first to use digital recording technology in every release. (He died on October 9, at 75.)

Harriet Klausner was Amazon.com’s most prolific book reviewer, a target of condescension and vitriol. She was a retired librarian who posted umpteen reviews a day, a grand total of 31,014 over the course of her reviewing life. (Most were on Amazon, but she also used Barnes and Noble and other, smaller sites). She gave every book four or five stars because, she said, if she didn’t like a book she just didn’t finish it. Her writing was…well, not great. One review reads: “The impoverished Star Kingdom of Manticore parliament debate continues over whether the isolated in a remote area of the galaxy nation needs a defenseless naval fleet loaded with obsolete in terrible shape ships and corrupt lazy offices.” In 2007, a group of snarky smartasses started The Harriet Klausner Appreciation Society, which did not appreciate Harriet Klausner. Klausner herself maintained that she was a speed reader, and had health problems and insomnia that made it hard for her to do anything but read. She admitted that she rarely spent more than an hour or two on a book. But conspiracy theorists were sure she was only pretending to read as a cynical ploy to get more books, which she’d then sell online to make a bundle. Her response? “Get a life. Read a book.” Amen, Harriet. (She died on October 15, at 63.)

Vera B. Williams was an author and illustrator of beautiful, timeless, powerful children’s books. If there is a baby or toddler in your life who does not possess the 1991 Caldecott-Honor-winning More More More, Said the Baby, you need to rectify that situation pronto. (Don’t buy the board book. Buy the hardcover. Williams’s lush, exuberant, vibrant paintings need full-size deliciousness to luxuriate in.) In an era before “We Need Diverse Books” was a rallying cry, Williams depicted Asian-American, black and multiracial families and showed fathers doing the active work of parenting. The text of More More More is as potent as the pictures, featuring the repetition and humor kids love along with the warm, inter-generational demonstrations of love parents crave. (A number of parents have complained about the book’s grammar, but they are morons who do not understand poetry.)

Williams also wrote emotionally complex books for older kids, often dealing with class issues: A Chair for My Mother is about a girl who’s determined to replace her mom’s comfy chair after the family loses everything in a fire, and Amber Was Brave, Essie Was Smart is an illustrated chapter book, told in verse, about two girls with a daddy in prison and a mom who has to work long hours to support them. Williams’s own family lost its home during the Depression, and her father was absent (perhaps imprisoned) for a long time. She studied painting with Josef Albers, was active in environmentalist and anti-war causes, named her son Merce after Merce Cunningham, illustrated a book by Grace Paley (of course) and served a month in jail for her involvement in a protest at the Pentagon in 1981. She was amazing.(She died on October 16, at 88.)

You know that poem that many of our congregations say during the Yizkor service, “We remember them”? “So long as they live, we, too, shall live, for they are now a part of us, as we remember them.” It’s true. We are none of us dead. We are merely…pining for the fjords.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.