On Sendak’s Childhood and the Inspiration for ‘Where the Wild Things Are’

A new book about writers’ relationships to death provides insight into the acclaimed illustrator’s life

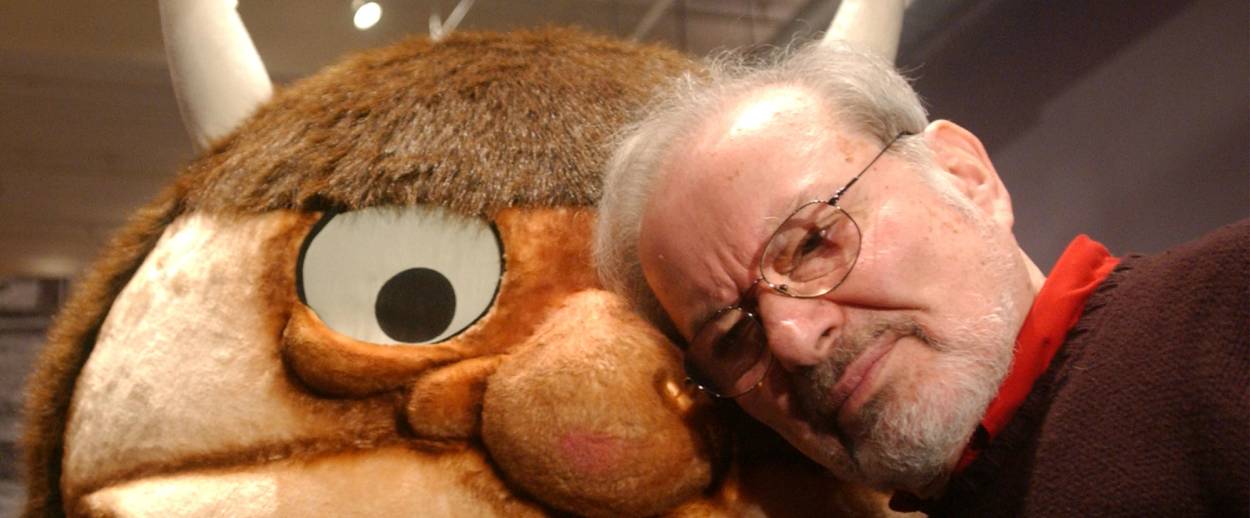

In 2014, when we reported on the fiery and beloved children’s book author/illustrator Maurice Sendak, his estate was embroiled in a lawsuit with a Philadelphia museum over items in his rare-book collection—in death, as in life, the man seemed to be perpetually caught up in an intense whirlwind of affect. (Last year, many pieces of artwork drawn by Sendak, who died in 2012, were on display at Sotheby’s.)

And we continue to learn new things about the man who “helped create childhoods for several generations,” as Tablet contributor Marc Tracy wrote about Sendak, the day after his passing. A new article in The Atlantic by Katie Roiphe—adapted from her new book on writers’ relationships with death—reveals that the tenor of Sendak’s life and work, with its violence and consuming emotion, was set early on, grounded in his Ashkenazi Jewish upbringing. For example, in a scene from Sendak’s childhood, Roiphe reports:

During one illness Maurice had as a toddler, his mother found him clawing a photo of his grandfather that hung above the bed; he was speaking Yiddish, even though he only knew English. She thought a dybbuk was trying to claim him from beyond the grave, so she tore up the photograph. She said she burned it, but years later Maurice found the torn-up pieces in a Ziploc bag among her possessions. He had a restorer put it back together and he kept it in his house, this grandfather calling him to the grave.

And later, writing about the origins of children’s literary classic Where the Wild Things Are, Roiphe writes:

Maurice said he dreamed up the idea of the wild things as an adult, at a shiva after someone had died, with his brother and sister. They were sitting around, laughing about their relatives from Europe. The relatives didn’t speak English. Their teeth were yellow. They grabbed the children’s cheeks. It was like they would gobble up Maurice and his siblings, along with everything else in the house. The wild things were Jewish relatives.

Finally, Roiphe quotes Pulitzer-winning playwright/screenwriter Tony Kushner, describing a conversation he had with Maurice:

I tell him I will visit him in Connecticut. “Great,” he says. “We can dance a kazatzkah!” “What kind of dance is that?” I ask. “A kazatzkah [a traditional Russian folk dance] is the Dance of Death,” he tells me. “Sounds good. Do you know the steps?” I ask. “Do I know them,” he says with glee, making a kazatzkah sound like the most fun imaginable, “I know those steps in every notch, every noodle, every nerve cell! Of course I know them! I’ve been rehearsing them all my life!”

Roiphe’s book The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End is released today, March 8th, by Dial Press. For more on Sendak check out Adam Chandler on Sendak’s response to his books being banned, and Sara Ivry’s meditation on mourning in the social media age.

Previous: ‘Wild Things’ for Sale

Rose Kaplan is an intern at Tablet.