What’s in Merrick Garland’s Name?

For better or worse, we must know. (And we found out.)

Merrick Garland. Merrick? Garland?

Within minutes of President Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland’s to the Supreme Court, the Jewish guessing game started.

Was Garland Jewish? Was a fourth Jewish justice about to join the High Court? (In Louis Brandeis’s day, even a single Jew on the Supreme Court was, for some, one too many.) And, mostly, how could there be a Jew named Merrick Garland?

For me, though, Garland’s religious background wasn’t a question. Forty years ago, my law school classmate Alvin Katz (Garland’s best friend in third grade, Katz insists) had touted the guy to me, and I’ve been following him ever since. I’d seen that long before his name perennially appeared with every Supreme Court vacancy, Garland had vindicated Alvin’s praise and predictions of success. I thought I knew a certain amount about him, and always assumed, with the usual ethnic pride, that he was Jewish.

Until Thursday morning, that is, when I awoke to some profoundly disturbing news. It came first from an item in Mike Allen’s daily Politico Playbook, which read:

TOP TWEET — @kenvogel: “real question … How does a Jew from Lincolnwood get a name like Merrick Garland? Sounds super WASP-y to me. … Mystery solved: Merrick Garland likely got WASPy name via WASP dad. Mom was Jewish; raised as MOT.”

It turns out that even before President Obama nominated him at eleven o’clock on Wednesday morning, it turned out that Garland—and his name—had already been the subject of puzzled speculation. The most surprising thing about the pick, Mike Madden of the Washington Post tweeted at 9:50, was that “ ‘Merrick’ is a Jewish name.” Nearly an hour later, at 10:43, Vogel, a Politico reporter, posed the “real” question Allen mentioned.

A minute later a Democratic strategist named Kenneth Baer weighed in with an explanation: “Protestant father.”

“For real? if so, would make sense,” Vogel tweeted back at at 10:55. At 10:58, Baer attributed the information to Wikipedia. “Mystery solved.” Vogel tweeted at 11:00, just as the Rose Garden ceremony began: (“MOT,” for the uninitiated, stands for “Member of the Tribe.”)

Appearing as it did in Allen’s highly-read and respected blog, Vogel’s revelation was disconcerting enough to me. But things got worse when I picked up Thursday’s New York Times, and read its front page profile of Garland.

“Friends say Judge Garland’s connection to Judaism runs deep,” it read. “His father was Protestant, but he was raised as a Jew—he had a bar mitzvah in a Conservative synagogue—and he spoke movingly Wednesday of how his grandparents left Russia, ‘fleeing anti-Semitism and hoping to make a better life for their children in America.’”

Suddenly, though, it appeared that two of those grandparents weren’t Jewish. While some applauded the news— there are currently no Protestants on the Supreme Court, and half of one is evidently better than none at all—I felt instantly deflated, though I also wondered why. Why is it we Jews are not only quick to claim someone as our own, but insist upon claiming all of him? For better or worse, though, we do: our fierce feeling of specialness is something we don’t want to share with anyone else. It doesn’t matter that because Garland’s mother is Jewish, Garland is as well, or that Garland’s wife had serious yichus, her grandfather having founded one of New York’s storied Jewish law firms and counseled Franklin D. Roosevelt. Our chauvinism knows no bounds, and tolerates no asterisks.

Fortunately, though, my pal Stuart Cohen was already on the case. Like Jews everywhere, and especially those of us born, like Garland himself, in 1952—this list also includes Katz and my high school classmate Jeff Cohan, who posted on Facebook Thursday morning that Garland had lived across the hall from him during their freshman year at Harvard—Stuart could dredge up his own Garland connections: having grown up on Chicago’s North Shore—he still lives there, in Highland Park—they were ample, if a bit tenuous.

Stuart had gone to New Trier West High School in Northfield, the first cousin of Garland’s alma mater, Niles West High School in Skokie, with people who’d later attended Harvard with the SCOTUS nominee. Stuart had attended the University of Illinois with Garland’s brother-in-law, and his accountant had been on Garland’s high school debate team. But more important than any of that, Stuart is a proud Jew, and a world-class genealogist. That’s a potent—even an unstoppable—combination.

Stuart, whose day job is in mortgage banking, spent much of Wednesday afternoon and evening at his computer, tracking down Garland’s past. His principal mission was to learn Garland’s original, or what Jewish genealogists sometimes call—mostly facetiously—his “maiden” name. (What’s in a name? Well, for Jews, it’s often the litmus test of their Jewishness.)

He started with the death notice for Garland’s father, Cyril, from 2000. From that, he turned to the U.S. Census of 1930, and learned that Cyril’s father was named Max. Then, going back to 1920, then 1910, he learned that Max Garland had been a grocer, and before that, a butcher, in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Max Garland’s neighbors there, he could see, all had Jewish names. (So many Jews in Council Bluffs, Iowa? Well, it wasn’t entirely preposterous: Ann Landers and Dear Abby, nee Esther and Pauline Friedman, had grown up in Sioux City, a hundred or so miles away.)

Within a couple of hours, then, Merrick Garland’s Jewish origins had been established to Stuart’s satisfaction. (There was soon additional, anecdotal corroboration from one of Stuart’s office mates, who ascertained that Garland’s bar mitzvah had taken place at the Lincolnwood Jewish Congregation. That is a highly traditional synagogue, Stuart knew, one unlikely to have held such a ceremony for the son of a non-Jewish father.) So when, sometime Wednesday afternoon, Stuart’s son, Harris, told his father he’d heard that only Garland’s mother was Jewish—that erroneous story appears to have migrated from the Forward to Wikipedia to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency—Stuart knew that was wrong. But Garland’s maiden name remained elusive.

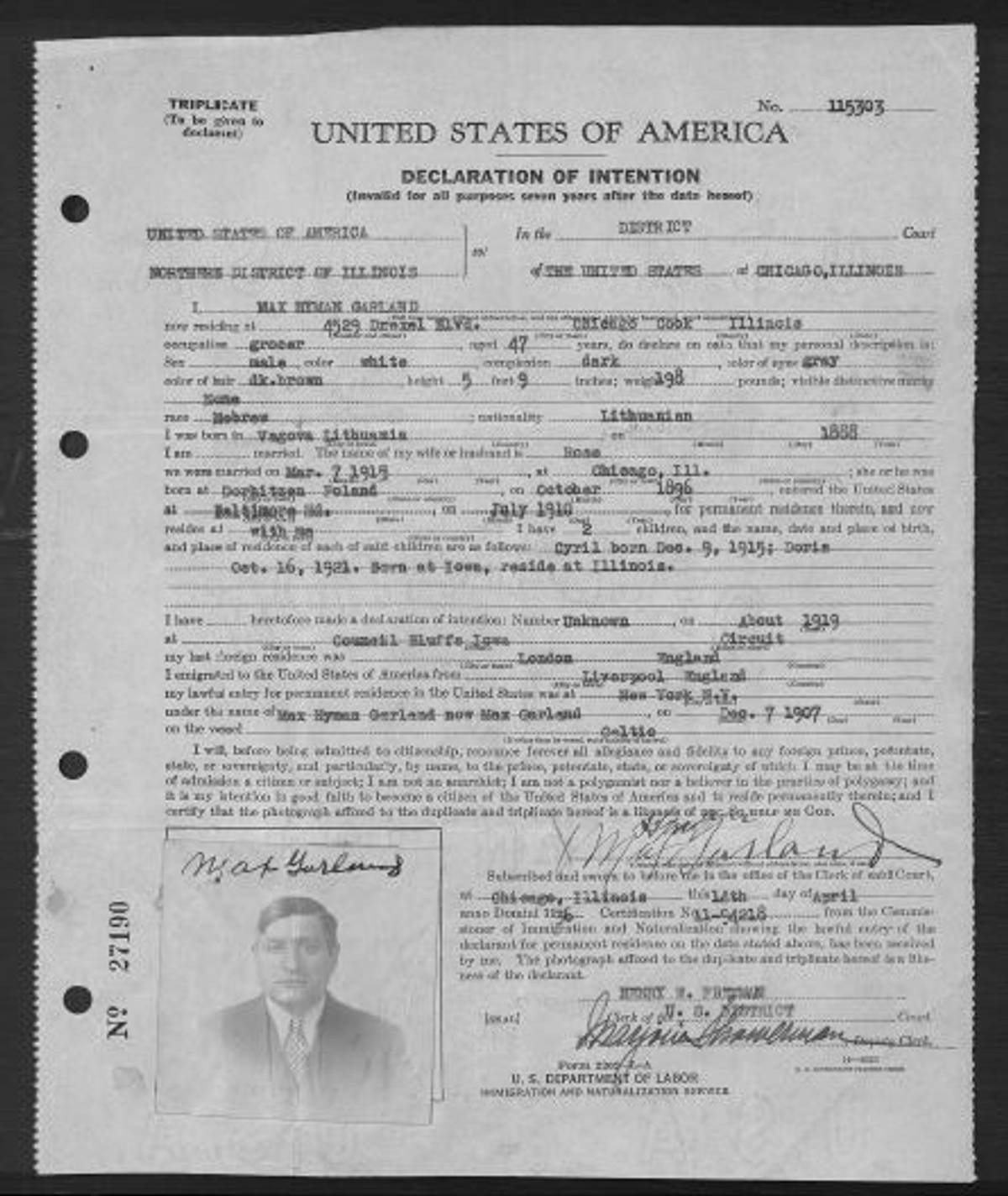

Initially unable to find Max Garland’s citizenship papers, Stuart feared he’d have to go down to the Federal archives on the Chicago’s Southwest Side, or request microfilm from the Mormons in Salt Lake City. But on Wednesday night, he found, digitized, Max’s application for citizenship, dating from the late 1930s. It included a photograph of Max Hyman (later, Harry) Garland, who had listed his race as “Hebrew,” and disclosed his native town: Vagova, Lithuania. It also detailed his arrival in the United States—from Liverpool in December 1907, aboard the Celtic, landing in New York. (His name did not seem to appear in the ship’s manifest, however.) His wife, Rose, was born in Poland, and came to Baltimore in 1910. But to his dismay, Stuart saw that Max Garland had traveled under the name of … Max Garland! Perhaps, Stuart surmised, Max had already Anglicized his name.

Further explorations revealed that Max Garland had died in Chicago in 1946, and that his father’s name had been Nakhman. Strictly by coincidence, Stuart also learned online that the Governor of Iowa, Terry Branstad, was Merrick Garland’s second cousin. Branstad’s grandfather, Louis Edward Garland, and Max Garland, had been brothers. (That Branstad’s mother married a Lutheran and that Branstad himself is now Catholic matters less than that he is a Republican, which could conceivably help Garland’s imperiled confirmation. Too bad Garland wasn’t nominated before the Iowa caucuses, when Branstad might have had more leverage.)

It was at this point that a good genealogist’s instincts kicked in. Strictly on a hunch that “Garland” had originally been “Garfinkel,” Stuart typed “Nakhman Garfinkel” into the Jewish genealogical site JewishGen.org. And sure enough, up he came. Merrick’s great-great-grandfather was named Leib Yitzhak Garfinkel, and that pretty much clinched it, for “Louis Edward” is very likely its English equivalent; Branstad’s grandfather was almost certainly named after him. Soon, Stuart had traced the nominee’s lineage back to his great-great-great-grandfather (Zelig), his great-great-great-great-grandfather (also Nahkman), and great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, born circa 1735 (Leib).

But there were others, most likely Jews, on the case. Or, more accurately, on the Times’s case. For as anyone who’s ever worked at the Times, as I once did, well knows, the surest way to determine whether or not you’re being read is to err on anything Jewish. It’s even worse than misquoting Shakespeare or Gilbert and Sullivan: you hear from everyone. And so it was here.

By the time Stuart contacted the Times on Thursday afternoon with his findings, he’d been scooped: the paper had already taken down the erroneous information, and posted a correction. “An earlier version of this article misstated the religion of the father of Merrick B. Garland, President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee,” it stated. “He was Jewish, not Protestant.”

That was all it said. But everywhere, Jews cheered.

David Margolick, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, is writing a book for Nextbook on Your Show of Shows. He’d appreciate hearing from those with memories or comments on the program: [email protected].