Jewish Food and the Recipes of Our Lives

‘Nourishing Tradition,’ a new exhibit at The Center for Jewish History in New York, shows that Jewish cuisine isn’t merely sustenance—it’s family history and connection

My bubbe died when I was 14. All her grandchildren—I was the oldest—remembered her black-and-white cookies with great fondness. Her children and their spouses, on the other hand, remembered the cookies as vile.

When I was in college, I decided to make the cookies for Thanksgiving. I found her box of recipes in my parents’ basement, and pulled out a stained index card with her recipe for “half moons.” I hadn’t seen her handwriting for half a decade, but I immediately recognized it from a zillion birthday cards. Holding that card, I felt a visceral connection to her. I made the cookies—and reader, they were disgusting: tooth-achingly sweet, crumbly, texturally gross. “Way to ruin my childhood memories, Marge,” my cousin Aaron said to me.

***

For better and worse, food is intricately connected to individual memory, family history, and cultural heritage. “Nourishing Tradition: Jewish Cookbooks and the Stories They Tell,” a small show at the David Berg Rare Book Room at the Center for Jewish History on East 16th Street in New York City, helps tell that story—of Jewish identity through food. The show’s up through September 9.

“Cookbooks reveal mobility and migration,” said Melanie Meyers, Senior Librarian for Special Collections, Reference, and Instruction at the Center, at an event last Wednesday night introducing the show. Waves of Jewish immigration and emigration are reflected in our cookbooks; they show how we cling to selfhood and place through recipes, using food to acclimate to new settings and mourn the ones we’ve had to leave.

Jewish food history is indeed a big tent. As Meyers spoke, I focused on a young man, who was also listening, wearing a t-shirt saying, “Our Chefs Shuck.” Here was a guy interested enough in Jewish culinary tradition to come to the show while unselfconsciously sporting clothing advertising trayf seafood.

“Nourishing Tradition” is the first show at the Rare Book Room to feature objects from all five partners at the Center for Jewish History: The American Jewish Historical Society, the American Sephardi Federation, the Leo Baeck Insitute, the Yeshiva University Museum, and YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. In about a month, they’ll add a copy of Mrs. Esther Levy’s 1871 Jewish Cookery Book on Principles of Economy Adapted for Jewish Housekeepers With the Addition of Many Useful Medicinal Recipes, And Other Valuable Information, Relative to Housekeeping and Domestic Management, the very first Jewish cookbook published in America. (At the moment, the show features a good facsimile.)

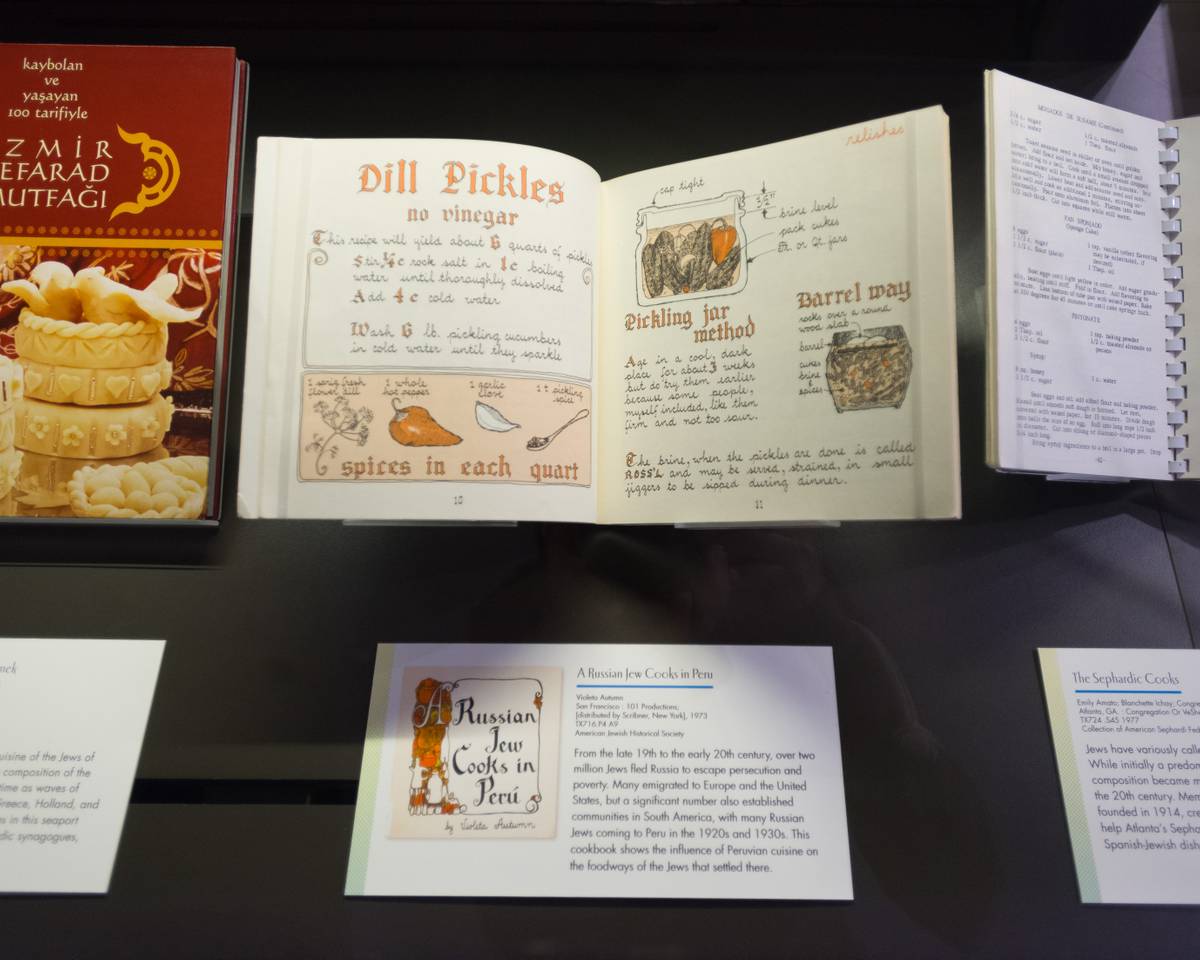

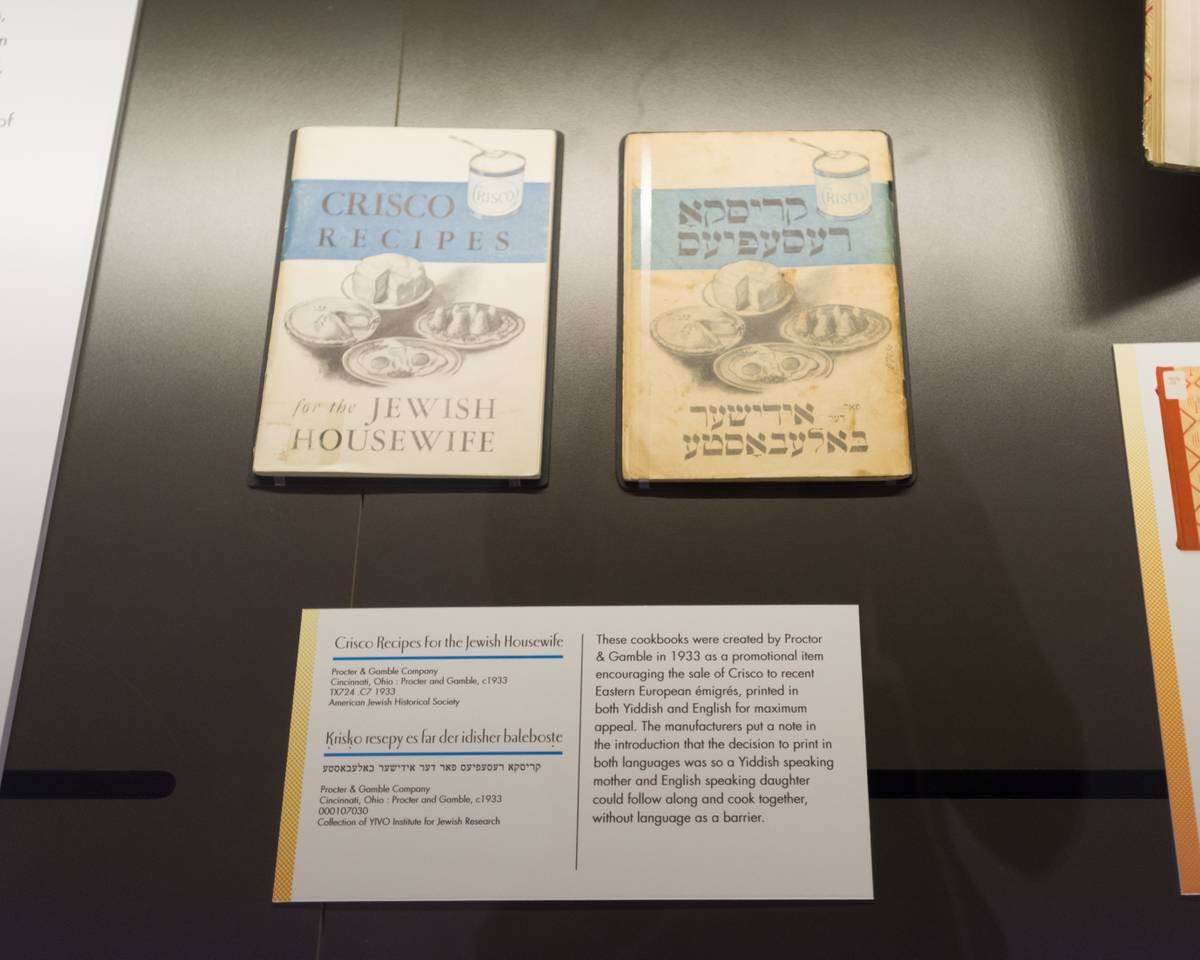

There’s a section of ephemera from product manufacturers who suddenly realized their products were kosher and they could woo a Jewish audience: Crisco Recipes for the Jewish Housewife (Krisko Resepyes far der Idisher Baleboste), a 1933 pamphlet published half in English and half in Yiddish, was designed for mothers and daughters to use together. There’s a Manischewitz cookbook and a cookbook from Wolff’s, best known for its kasha. (“All the things you can do with buckwheat!” noted Meyers.) There’s 1973’s A Russian Jew Cooks in Peru, with a recipe for “Papas Rellenas, or Gefilte Malaiklaj Peruvian Style.” It’s a charming, handwritten, Moosewood-Cookbook-ethos guide with little hippie-style cartoon illustrations. Bonnie Slotnick, the antiquarian cookbook impresario who spoke later in the evening, told us a juicy tale of a mysterious older gentleman who asked her to find him a copy of this book, telling her that he too had been a Russian Jew cooking in Peru. Slotnick later discovered he’d actually been the country’s finance minister, now on the lam, under investigation for mismanaging over $140 million in state funds. “He wants another copy of the cookbook,” Slotnick noted. “The next time I find one I’m going to charge him $140 million and send most of it to the people of Peru.”

Touchingly, the show also features artifacts from Elsa Oestreicher, a cooking teacher and cookbook author in Berlin who was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942. There, she worked as a cook. She survived the war, immigrated to the United States and died in New York in 1963. The show features her DP Camp identity card, a ration card, an identity badge from Theresienstadt, and a beautifully calligraphed poem (with an accompanying English translation) from a fellow inmate, a testament to Oestreicher’s goodness and talent. A snippet:

What is of value remains of value,

In Berlin or Theresienstadt.

The benevolent housewife teaches and cooks

And also fills our stomachs up in the camp,

Works with understanding and with heart,

Preventing stomach pains.

At the end of the evening, Slotnick gave a brief presentation, sharing a story about a woman searching for a copy of her mother’s favorite cookbook, with which she’d been buried, and telling of zillions of American Jewish cookbooks filled with recipes for lobster, as American Jews fervently tried to assimilate into their new-ish country’s culinary ways. Afterward, there was a crazed stampede of elderly Jews toward a table groaning with colorful snacks: Grilled veggie tarts, fish on skewers, Israeli salad stuffed into cucumbers. I think. I only caught a glimpse before the table was swarmed over.

Related: I Am Charlotte’s Tsimmes

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.