Inside the boutique Eden Hotel, located in Jerusalem’s leafy Talpiyot neighborhood, a certificate on the wall declares: “The community can eat with us safely.” It’s signed by the hotel’s owner and by an Orthodox rabbi.

This certificate—with its vague wording and two authoritative signatures—is representative of how Eden and a growing number of Israeli restaurants are communicating to customers that their food and kitchens are genuinely kosher. These certificates are not administered by the state-run Israeli rabbinate—the only legal body able to supervise kosher certifications in the country—but they nonetheless communicate kashrut to customers without breaking the law.

The rabbinate has long been accused of corruption when it comes to kosher certification, and there is growing public concern about the lack of competition in the kosher-certification sector, which a recent finance ministry report found adds five percent to the cost of food. In order to bypass the Israeli rabbinate’s stronghold on this certification process, restaurants like Eden have had to get creative, particularly when it comes to the language they use on the certificates they display.

A recent Supreme Court ruling in Israel strengthened a law that only allows the rabbinate—and no other entity or person, including individual rabbis—to issue supervision certificates that use the word “kosher” and other terms associated with the upkeep of Jewish dietary laws, such as “halacha” and “hashgacha.” Restaurants that use these words outside the auspices of the rabbinate are subject to hefty fines.

The Eden and one other Jerusalem restaurant that has worked around the Israeli rabbinate, said that they are happy with an alternative inspection service run by an Orthodox rabbi named Aaron Leibowitz, and that a growing number of diners seem familiar with the (necessarily) vaguely-worded certificates. It is another sign of the growing grass-roots efforts in Israel to conduct religious life without relying on the rabbinate.

“The idea of something alternative appealed to us,” said Line Djamchid, owner of the Eden, which has kept a kosher kitchen, and whose staff has refrained from cooking on Shabbat, since the hotel opened six years ago. “We didn’t want to use the rabbinate.”

Three years ago two Jerusalem restaurants were fined for allegedly using the word “kosher” outside the auspices of the rabbinate. They took their case against the state-run institution to court, arguing that the ban on the word kosher infringed on their right of freedom to do business. With help from the Israel Religious Action Center, which advocates for pluralism and the freedom of religion, the restaurants’ case eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court, before their appeal was ultimately denied.

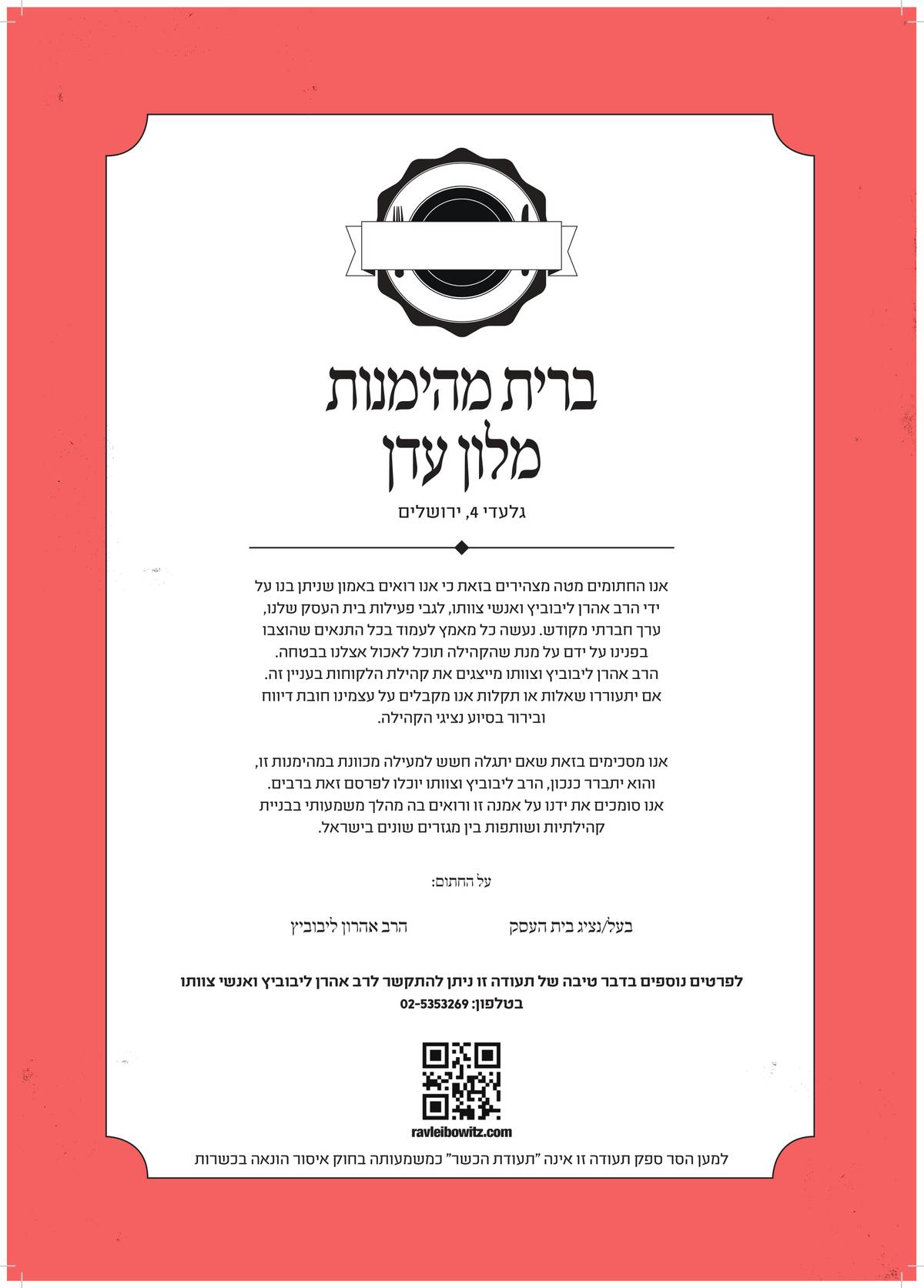

Hashgacha Pratit’s new kosher certification. (Image courtesy of Hashgacha Pratit)

Disappointed by the June ruling that only upheld and strengthened the existing law, the restaurants have requested an additional hearing.

Meanwhile, Aaron Leibowitz, the Orthodox rabbi whose name is on the certificate in the Eden and 26 other restaurants, including those that are plaintiffs in the court case, says things are going well for his alternative kosher-certification service, called Hashgacha Pratit (meaning, “private supervision”) and registered as a non-profit organization.

Leibowitz, who is not involved in the court case, has had to change the wording on the certificates to abide by the new rules. This meant taking off the name of the organization, Hashgacha Pratit, because the word “hashgacha” is forbidden, as well as adding a sentence declaring “this certificate is not a “kashrut certificate” in terms of the Law to Prohibit Fraud in Kashrut.”

“Our brand has become stronger,” said Leibowitz, who is also a Jerusalem city council member. “Things are better than ever,” he said, adding that there are about 30 restaurants on the waiting list for his supervision.

Israeli media has reported that the rabbinate is considering ways to improve the kosher-certification service, including privatizing parts of it, but the rabbinate has not confirmed any concrete plans.