Perspectives About Psychoanalysis, From Both Sides of the Couch

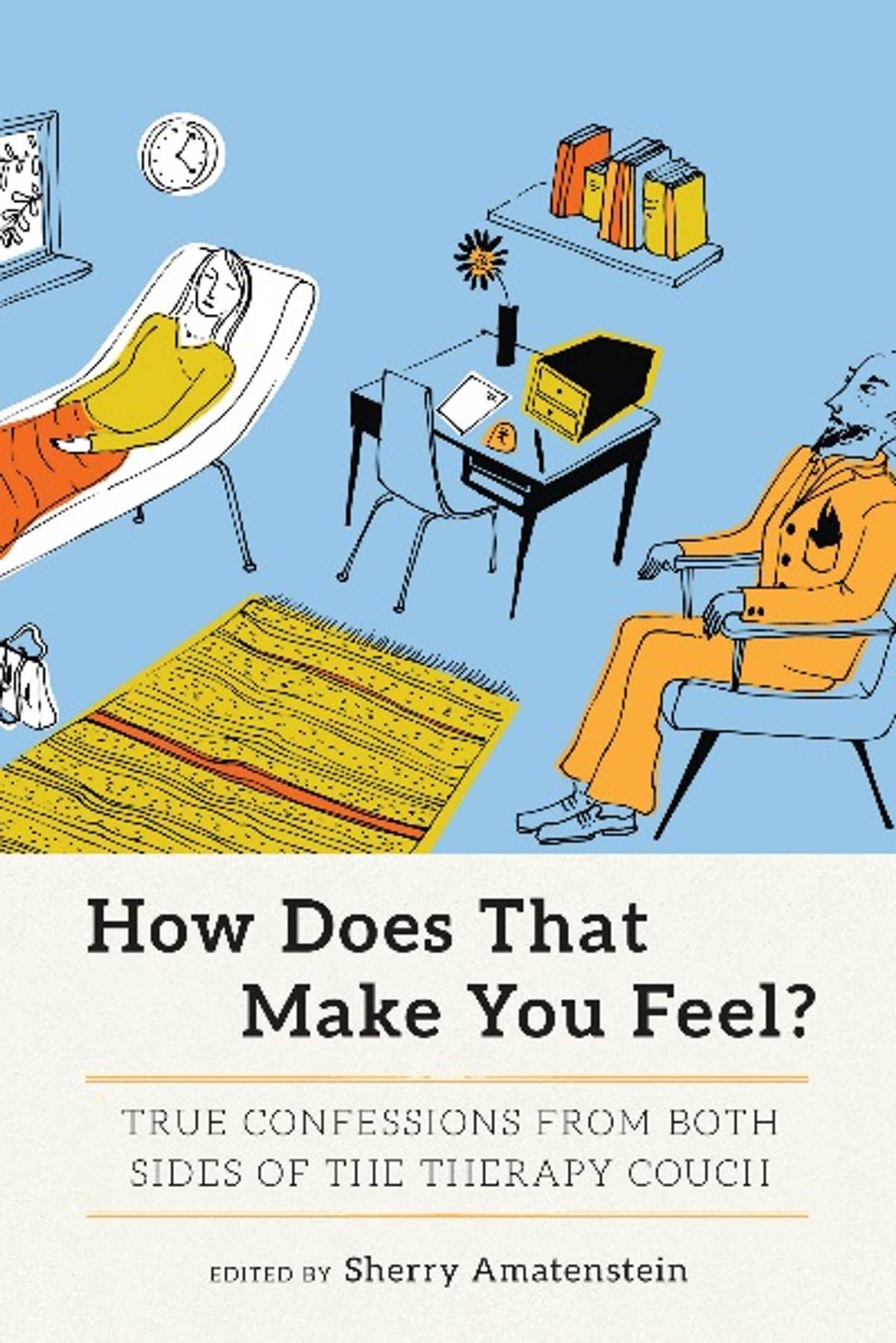

‘How Does That Make You Feel?’, edited by a New York-based social worker, is a collection of essays written by both therapists and patients about the process of psychoanalysis

Many Jews wear their neuroses as a source of pride. We “chosen ones” were born with the ingredients for anxiety: high intelligence, fine-tuned sensitivity, and a horrifying history of persecution. Alienated, made fun of, exiled and slaughtered—no wonder we invented psychoanalysis.

A new book called How Does That Make You Feel?, features essays by 13 therapists and 21 patients (but no shrink/shrinkee pairs), many of whom are Jewish, about the process of therapy from both sides of the couch. The collection is edited by Sherry Amatenstein, a New York City-based licensed clinical social worker, and an author of three books on relationships.

Amatenstein’s aim, she said, was to obliterate boundaries through personal and provocative stories, to “humanize shrinks to the shrunks. I wanted patients to see that therapists are neurotic as hell, too,” she said.

Amatenstein asked her contributors to be honest and open about something they would normally keep hidden, a sort of meta example, in a sense, of work that goes on in therapy sessions already. “Writing is about opening your ego,” said Amatenstein. “In therapy you don’t expect to be judged, but when you’re writing for an editor, you do.”

In her essay, Binnie Klein, a therapist with a radio show, talks about navigating the changing doctor-client boundary issues. “We’re being Googled [by our patients],” Klein writes. “Privacy no longer exists. The delicate and important balance of public versus private has preoccupied us since Freud’s notion of the analyst as a blank screen.” (Amatenstein, however, was quick to point out a bit of irony: “[Freud] vacationed with his patients!”)

Jewish culture themes abound in the book, including the universal tropes of love, loss, jealousy, anger. And if it’s not one thing it’s our mothers. Therapist Beth Sloan asks herself, “Has my drive been solely about proving to my narcissistic [Jewish] mother that I am indeed worth her sagging labia?” Estelle Erasmus, whose parents unknowingly sent her to a pedophile therapist, wrote about her mother, “She never met a boundary she couldn’t or wouldn’t cross.”

Amy Klein’s “My Therapist’s Mistake” sees therapy as “something you did to get help with a specific problem, like hiring an SAT tutor.” She chose secular atheist “Dr. X” because he “knew nothing about my Modern Orthodox Jewish community or its continuing stranglehold on me.” Former Seinfeld writer Charlie Rubin wrote about the high-end Jewish boys summer camp he went to as a kid, and the time his father came for a visit. “It was such a shonde!” said Amatenstein.

And there’s author Susan Shapiro (Speed Shrinking), a self-described “shrinkaholic” and “therapy-lifer,” who describes lining up a UN of advisers—an Indian psychopharmacologist, a Middle Eastern hypnotherapist, a Jewish Jungian astrologer—to meet with shrink-seekers for three minutes to exchange numbers a la speed dating. (The annual, free event to benefit New York-based AIDS charity Housing Works was featured on the CBS Morning Show and became a hit on YouTube. This year’s benefit will be held on September 6, to celebrate the release of How Does That Make You Feel?)

Amatenstein attributes becoming a therapist to being a child of Holocaust survivors. “Growing up, I heard all the stories,” she said. “My father was at Auschwitz and had to watch his parents and little sister walk away knowing they were going to the ovens. My mother was sent to a work camp. I never knew my grandparents.” She grew up hearing other people’s pain and wanted to ease their suffering. She hopes this anthology is another step toward that goal.

“The book, “she said, “covers the whole range of what it is to be human.”

Previous: These Graphic Bios About Freud, Marx, and Einstein Belong on Your Summer Reading List

Related: Becoming Freud, the Making of a Psychoanalyst by Adam Phillips

Dorri Olds is an award-winning writer whose work has appeared in book anthologies and numerous publications including The New York Times.