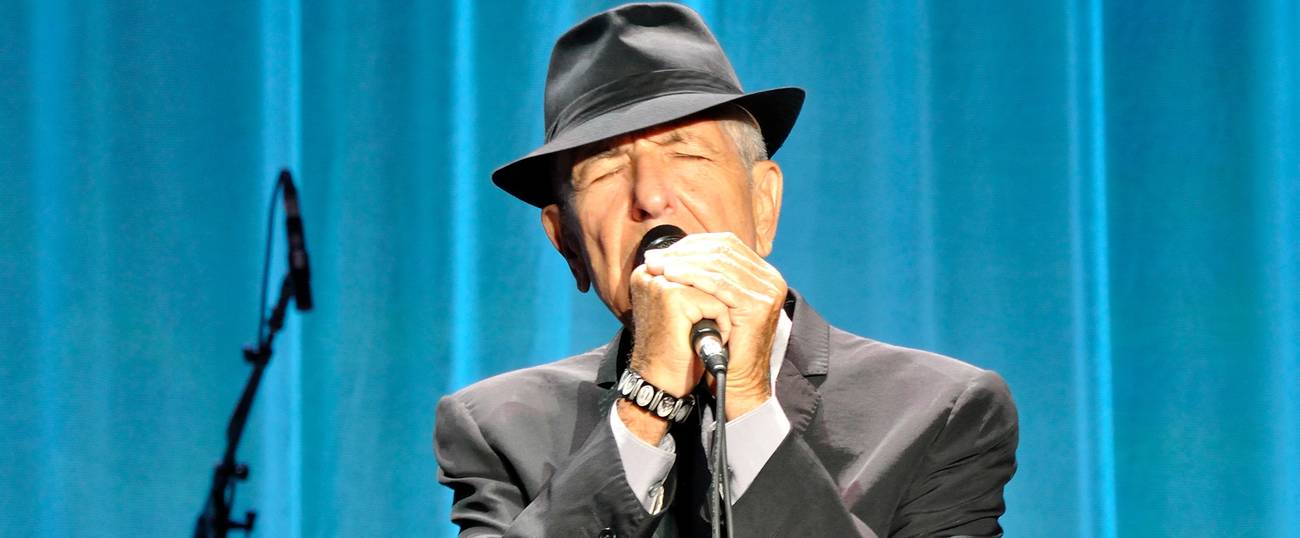

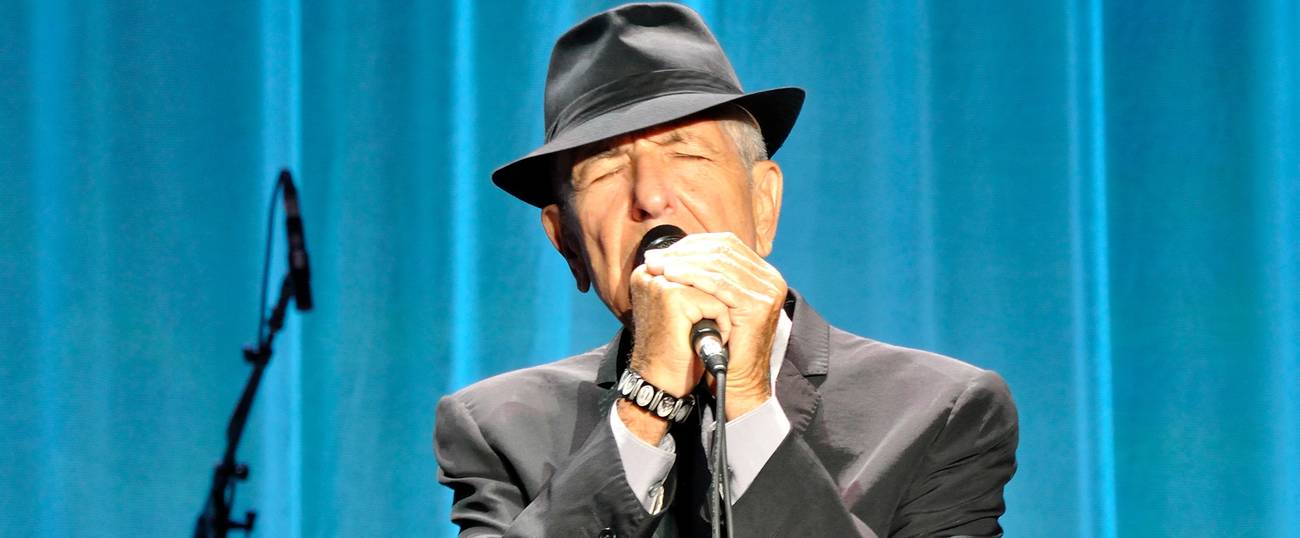

To Be Leonard Cohen

A tribute to the man who’s influenced my entire songwriting career, on his 82nd birthday

I used to hope in vain to be Bob Dylan, or the next Bob Dylan, or just Dylanesque. Then I realized it was pointless. Bob Dylan achieved his immortality in his early 20s and everything he did thereafter, while often spectacular, just built on the myth of his halcyon youth. And so, at the age of 40, I’ve curbed my dreams of becoming the next Bob Dylan. I still, though, find it entirely reasonable to hope to be the next Leonard Cohen, who turns 82 today.

In his rise from minor literary personality (in his late twenties), to underground poet-musician (early thirties) to arena-filling songwriter-legend (through the next five decades), he’s proved that youth is cute but that age brings authority and power: In the last 50 years, he’s written the kinds of songs that feel less like grains of mercurial sand and more like immortal mountains.

I first discovered Leonard Cohen in high school, as I became casually intrigued by the Eskimo who “never got warm.” In college I wallowed in the dark despair of “The Avalanche” as I shelved books in the work-study cave at Yale’s Mudd Library. I evaporated over the course of a summer listening to The Death of a Ladies’ Man while I practiced a life in which I “went for nothing, if [I] really want[ed] to go that far.” When I found myself moving from amateur to serious songwriter (in Dresden, Germany, no less), I covered “There is a War” from New Skin for the Old Ceremony and felt the power of performing Cohen’s words, which I know influenced my own words from then on.

As a 24-year-old singer-with-a-guitar in New York, a performance of my serious songs garnered audible whispers of “he’s like Leonard Cohen,” which thrilled me like nothing else. But Cohen didn’t just influence me as a writer or solo performer; when I listened to his 1979 concert album (released in 2000), I paid careful attention to the way he graciously introduced his individual band members in the middle of songs, after their solos or even just a particularly nice riff. “That was Roscoe Beck on fretless bass,” he’d say. I did the same when I got my band The Randy Bandits going (“That was Jay Buchanan on upright bass”).

I also paid homage to his look. I treasured my band photo in which I sat with a Cohenesque expression on my face, as I somehow captured his calm yet provocative persona in my gaze. I frequently wore suits like I pictured Leonard Cohen would wear and tried to hold myself as he would at the microphone, even as the front man of a band whose style was raucous, silly, sincere, and pleasantly unhinged—not exactly in the vein of Leonard Cohen.

While his influence was great through my band’s peak years, it wasn’t until we started slipping away from each other (as bands do) that I found myself truly needing the example of Leonard Cohen. The loss of my band coincided with the birth of my first son. My days were consumed with swapping adjunct teaching hours and childcare as my wife worked from home and swapped equally. The songs I wrote were meant for an audience of one—my infant son—who usually began crying the moment I started singing. One hopeless afternoon, I put on a DVD of Leonard Cohen’s 2009 London show and my son was miraculously transfixed.

I once again found myself studying the songs and performance style of a man now old enough to make jokes about having once been a 60-year-old “kid with a crazy dream.” My son took to wearing a hat like Cohen’s (inexplicably referred to as his “Drooka-Mamma” hat) and insisted on hearing a playlist of Cohen’s songs to ease him into night-night. I drew on the power of the Drooka-Mamma (really, don’t ask) when I asked a female friend to sing with me as I lined up some gigs to explore my more blatantly Cohenesque songs. This phase may or may not have passed, and now my son prefers Adele (to each their own), but I suddenly find myself in another singer-songwriter role as “The Jewbadour” for the Unorthodox podcast. Cohen, meanwhile, is releasing a new album this fall. The title track from You Want It Darker was also released today.

There, here, again I return to Leonard Cohen, the “little Jew who wrote the Bible.” “Hineni, Hineni, I’m ready, my Lord,” he sings now. As my aunt Debbie says, “You feel him in your kishkes.” And it’s true: Every time I hear him or even just read about him, I feel compelled to pick up my guitar. Mr. Cohen, I salute you and celebrate you. And if I may quote you from your most recent album Popular Problems, “You Got Me Singing!”

Previous: Happy Birthday, Leonard Cohen!

Miley Cyrus as Leonard Cohen? Hallelujah.

VoxVault: Leonard Cohen’s Long, Strange, Sometimes Tortured Road to Mastering His Own Sound

Jim Knable is a produced and published Off-Broadway playwright, a singer-songwriter and band leader of The Randy Bandits, and a writer of articles like these. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two sons.