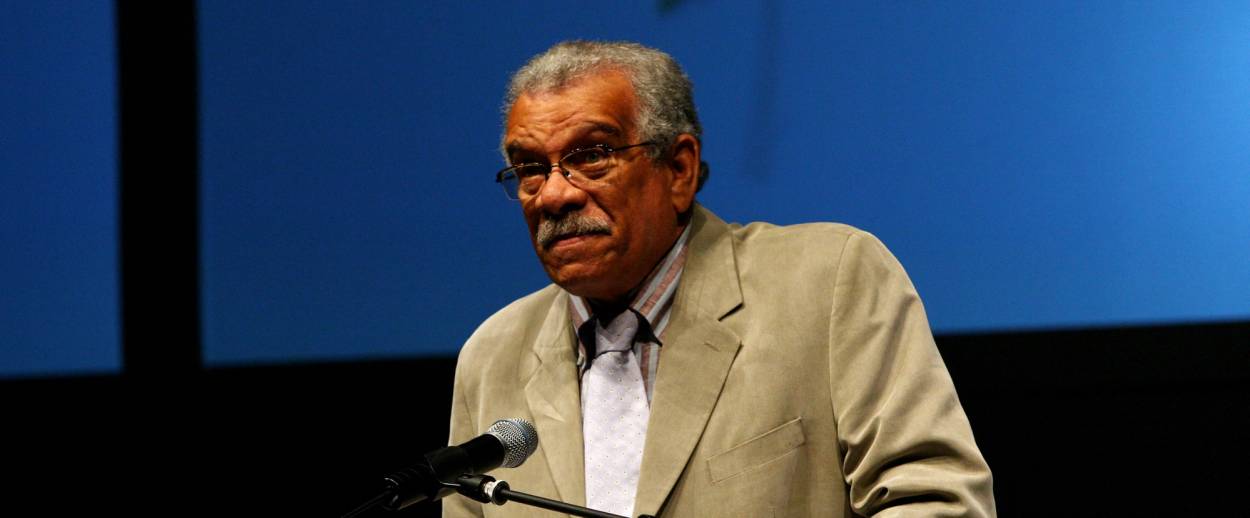

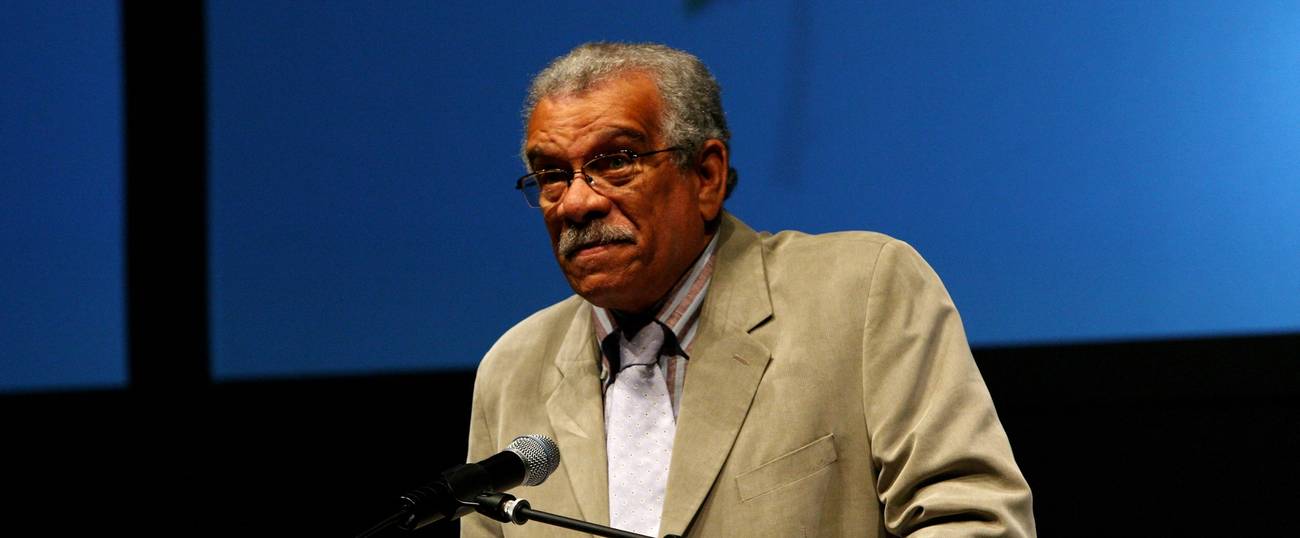

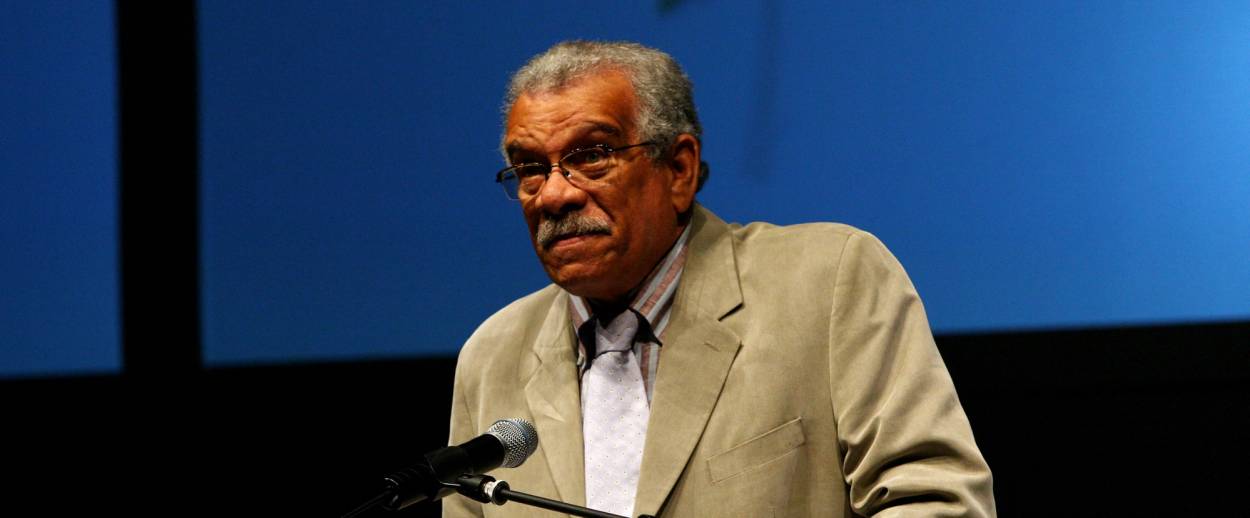

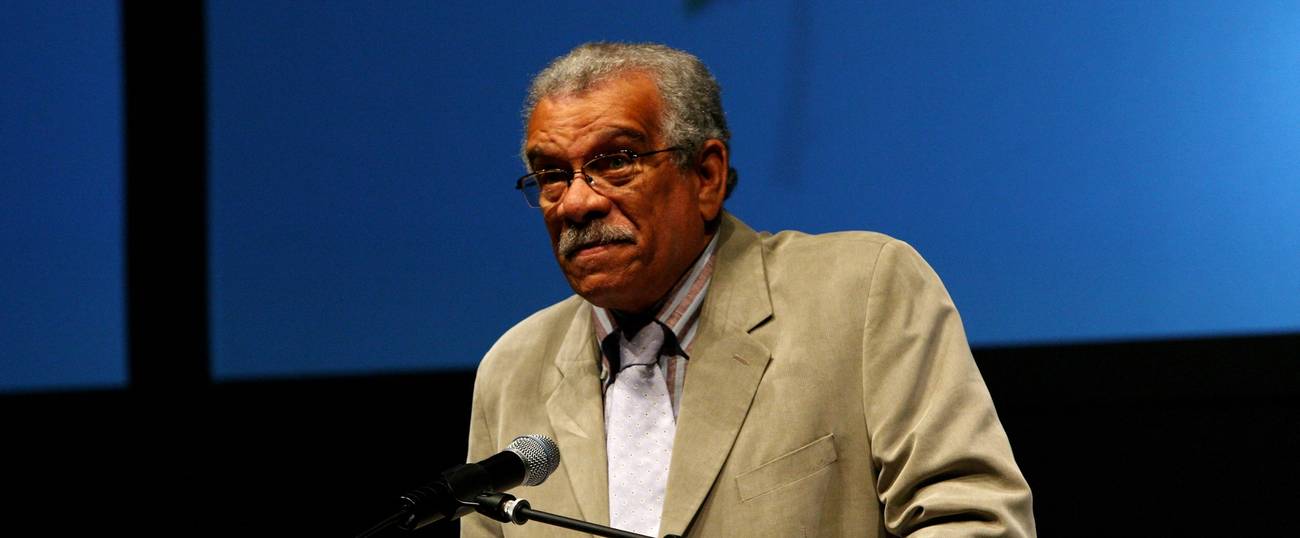

Celebrating Derek Walcott, a Caribbean Poet With an Avid Interest in an Unusual Jewish Painter

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet turns 87 today

Today is the 87th birthday of Caribbean poet Derek Walcott, winner of the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. Walcott’s poetry often explores colonialism and post-colonialism through the lens of his complex identity as the mixed-race descendant of African and European ancestors. His poetry draws upon biblical and scriptural sources, as well as literary epics. A frequent subject for Walcott is the sea, as Tablet columnist Adam Kirsch has discussed, which one would expect from a writer who grew up on an island.

What is perhaps less expected from Walcott’s oeuvre is his interest in the Jewish Impressionist and post-Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro. Walcott connects to Pissarro through their shared Caribbean origins: the painter, whose plein air scenes of industrialization and the French natural landscape were characteristic of his milieu, was born in St. Thomas before his family relocated to France. Born Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro, his mother was a French Jew, and his father was of Portuguese Jewish heritage. Their marriage was controversial according to Jewish law, because his mother had previously been married to his father’s uncle; as a result, they were somewhat excluded from the Jewish community in St. Thomas (also home to the second-oldest synagogue in the Western Hemisphere), and young Camille Pissarro attended an all-black primary school.

Perhaps Walcott, as a mixed-race descendant of both the colonized and the colonizers, identified with this experience of marginalization by not only the dominant culture but by one’s own community. Perhaps he identified with Pissarro’s experience as a religious minority (Walcott’s family was Methodist, and St. Lucia was majority Catholic). He certainly identified with Pissarro as an artist: Walcott, like his father, is a painter as well as a poet, although he is better known for his poetry.

In Tiepolo’s Hound, a book-length poem, Walcott explores the relationship between painting and writing, and tells Pissarro’s story, drawing upon (no pun intended) another of his similarities with Pissarro as he imagines Pissarro’s relationship to his homeland:

Doubt was his patron saint, it was his island’s,

the saint who probed the holes in his Saviour’s hands

(despite the parenthetical rainbow of providence)

and questioned resurrection; its seven bright bands.

Saint Thomas, the skeptic, Saint Lucia, the blind

martyr who on a tray carried her own eyes,

the hymn of black smoke, wreath of the trade wind,

confirming their ascent to paradise.

Watch Walcott read from Tiepolo’s Hound in 2008:

Miranda Cooper is an editorial intern at Tablet. Follow her on Twitter here.