Lessons From Sarajevo’s Jewish Refugees

In 1992 I traveled to Zagreb to help displaced persons fleeing Bosnia and Herzegovina. Years later, I visited Sarajevo and pondered the fragility of freedom.

I had so much to make sense of when I first arrived in Croatia at the height of the Yugoslav Wars more than two decades ago, as conflict raged between Bosnian Muslims, Orthodox Serbs, and Catholic Croats in the wake of Yugoslavia’s collapse. But it’s only now—in this tense climate of friends unfriending friends over issues, isms, and ologies—when I find myself longing for civility and kindness and peaceful discourse, that I finally understand how easy it is for things to fall apart.

It was November 1992, and Sarajevo had been under siege for months already. Jews were caught in the crossfire, but they were neither the target nor the scapegoat. The Sarajevo Jewish community, with assistance from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and other organizations, extended humanitarian aid to its fellow residents, regardless of their religion. It also coordinated with JDC to evacuate more than 3,000 people to safety—by plane until the airport shut down, and then, in bus convoys that had to pass through 38 military checkpoints on the precarious route to Croatia, where the refugees dispersed to a transitory, neither-here-nor-there era in their lives.

My planned arrival in the country was timed so I could greet one of the convoys heading towards the coastal town of Split. That gave me two days to pack for an almost six-month assignment in Zagreb to help manage JDC’s refugee aid program and assist Jewish refugees and their families staying in the capital. I had no idea what I’d find there. The word refugee was still surreal to me. The ethnic battles and humanitarian crises on the ground remained tragic intangibles, somewhere far away on CNN and the front pages.

But before I could board the plane and before I got to Split and met the exhausted and often malnourished refugees who emerged from that convoy, I had to tell my mother I was heading to a war zone, reassuring her I’d be a safe enough distance from the fighting. If I’d had time, I might have spent it worrying with her, yet I focused instead on getting a language guide called Just Enough Serbo-Croat, weatherproof shoes, and a shapeless, utilitarian winter jacket. Hours before my flight, I filled a second duffel with paperbacks, some kosher staples, enough toiletries to stock a Duane Reade, and, for some reason that still confounds me, a can of Static Guard.

As if I’d done this my entire life, I soon found myself sitting at a desk on the third floor of Zagreb’s Jewish Community building drinking Turkish coffee in a circle of Bosnian Jewish newcomers to the city. Some had arrived with the convoy I met in Split. Others came earlier or later. To round out their days, they either volunteered or just passed the time in the refugee aid office, filling the empty space once occupied by their regular lives, pushing out their longing for what they left behind and their worry about the future.

It was not the first time in history neighbors and friends—who shared a culture and a language and maybe even a first kiss, whose children played together, who took the same tram to work, who argued about soccer over a shot of rakija, and who bought their daily bread at the same bakery—had turned against one another from one day to the next. But of course, it’s never really sudden. The feelings that had burst into flames were old kindling long hidden in a tinderbox. Still, we rarely discussed these things in the office, not while filling out visa applications or drinking our coffees or helping those in our care maneuver over a bureaucratic hurdle.

Instead, we talked around them, and I hung on those stories, from the war and from before it. Elderly refugees, too familiar with displacement and loss from World War I and the Holocaust, spoke proudly of their Sephardic heritage and their days fighting with Tito’s partisans during World War II. Others recalled family left behind in Sarajevo and the everyday bits and pieces, like cooking dinner before gas, water, and food disappeared from the besieged city; it became too dangerous to be in the kitchen anyway, near the window blown out by a sniper. And there were the tales of reckoning, of the moment when you must choose how you want to remember your old life and what you need to start again, then squeezing those items into the two small suitcases you’re able to carry out of the city with you.

“You’re one of us,” they’d tell me, taking the edge off some of the disjointedness I felt being there alone.

Their generous claim that I had also been uprooted by the war was true in a way—I would never have come to Zagreb otherwise—but of course, it also wasn’t true at all. And yet, when I received a new field placement in neighboring Hungary, I wasn’t ready to leave them. I felt out of sorts in my flat in Budapest, as if I didn’t belong anywhere.

What I recall of those months in Croatia returns in short, loud bursts, like thunder, before going silent as if none of it ever happened. I watch the experience like I’d screen an old film, hardly recognizing myself, though I know it’s me because I can still feel all of it pulsing in my veins. It had been a long while when, on the day I decided to write this, I reached for my coat and found myself transported back to the basement of the Jewish Community building in Zagreb.

One morning, the head of the refugee aid team and I were unpacking a donation of lightly-worn winter coats and jackets. We had more than we needed for our caseload and agreed where to distribute the rest. About to emigrate, he selected a coat that would suit his new life then urged me to take one for myself. I refused. It wouldn’t be right. He pushed, and I pushed back, digging my heels into the principle of it until finally, he threw up his hands in exasperation as if to shout, “You are one of us! You cannot wear that hideous jacket of yours again!” We laughed, about the coat and other misconceptions—his of Americans, mine of ex-Yugoslavs—and I agreed to let him choose something for me. Back in our offices, he carried off my other jacket and I never saw it again.

By then, I’d outgrown my copy of Just Enough Serbo-Croat, the Serbo crossed off by someone when I wasn’t looking. I’d read through my stack of paperbacks and watched my coffee circle shrink as families, reunited with the arrival of subsequent convoys and armed at last with immigration visas, began to make their way to new lives in other places in Europe, Canada, Australia, and less frequently, Israel and the U.S. The Static Guard remained untouched. I would never be the same.

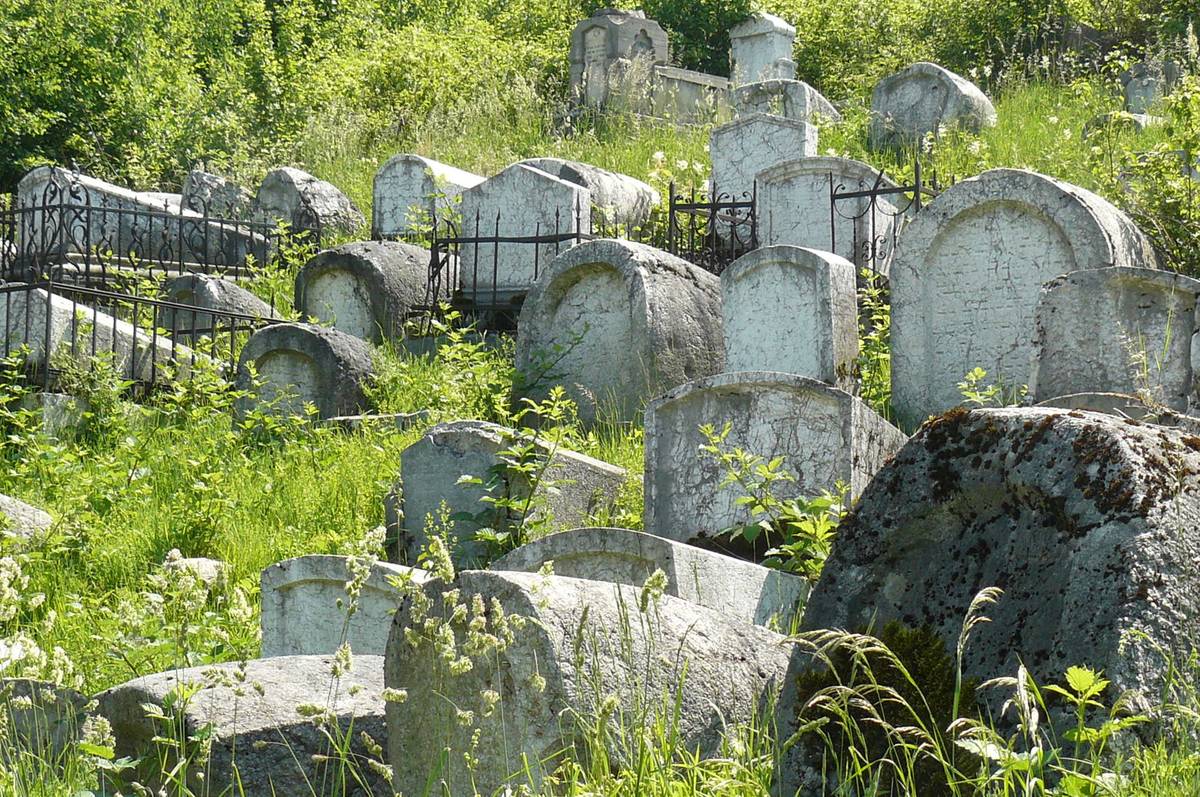

Years later, after the ink dried on the peace treaty ending the war, I traveled to Sarajevo for the first time. We stayed in the newly restored Holiday Inn, an icon of the 1984 Winter Olympics and the shell-pocked backdrop for journalists reporting during the fighting. We drove up the mountain slope to the old Jewish cemetery, not yet fully cleared of mines, where I shuddered with the knowledge that snipers had taken in the same sweeping views. Still, in the silence of that cold, rainy morning, it was easy to trick the mind into wondering whether it really happened, so when our driver offered me an empty mortar shell as a souvenir (“They are very popular with the tourists,” he assured me) I found myself saying yes.

My memories of those long-ago months in Zagreb are wrapped up with that empty brass shell now, and they hover like a ghost that puts its hand over my mouth unless I’m certain I’m in like-minded company. I’m grateful it’s here, as much for the past as for the future. It is a haunting reminder of the ultimate that can go wrong between people when we let the fragile commodities of civil discourse, kindness, and appreciation for what differentiates us slip right through our hands.

Merri Ukraincik is a blogger and essayist who is at work on a memoir. Follow her at merriukraincik.com.