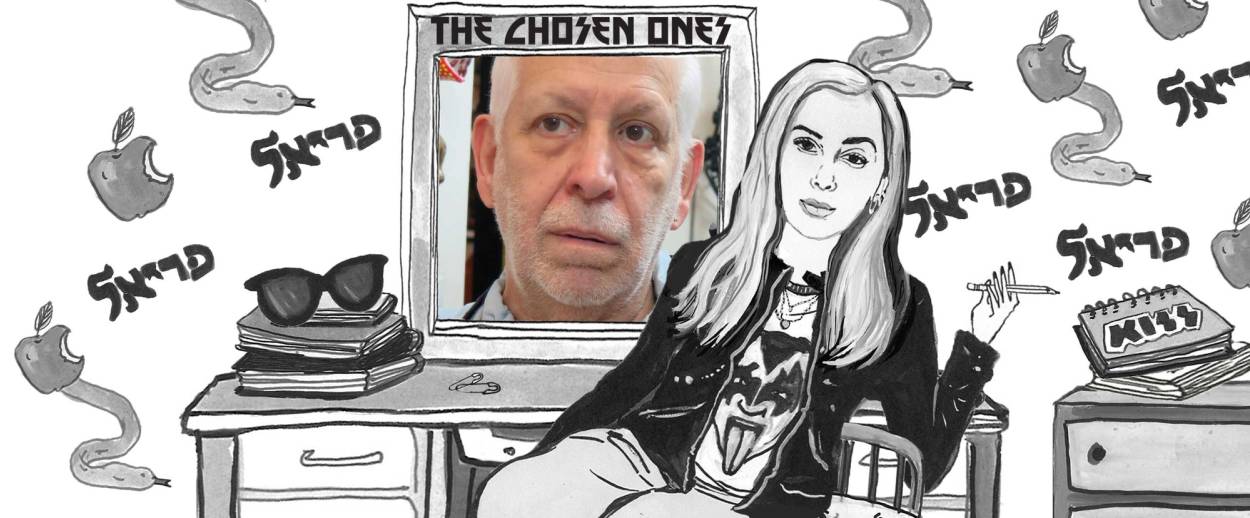

The Chosen Ones: An Interview With Lee Brozgol

The artist and social worker on residing on the Lower East Side, making ‘death head masks,’ and being shielded from anti-Semitism as a kid in Chicago

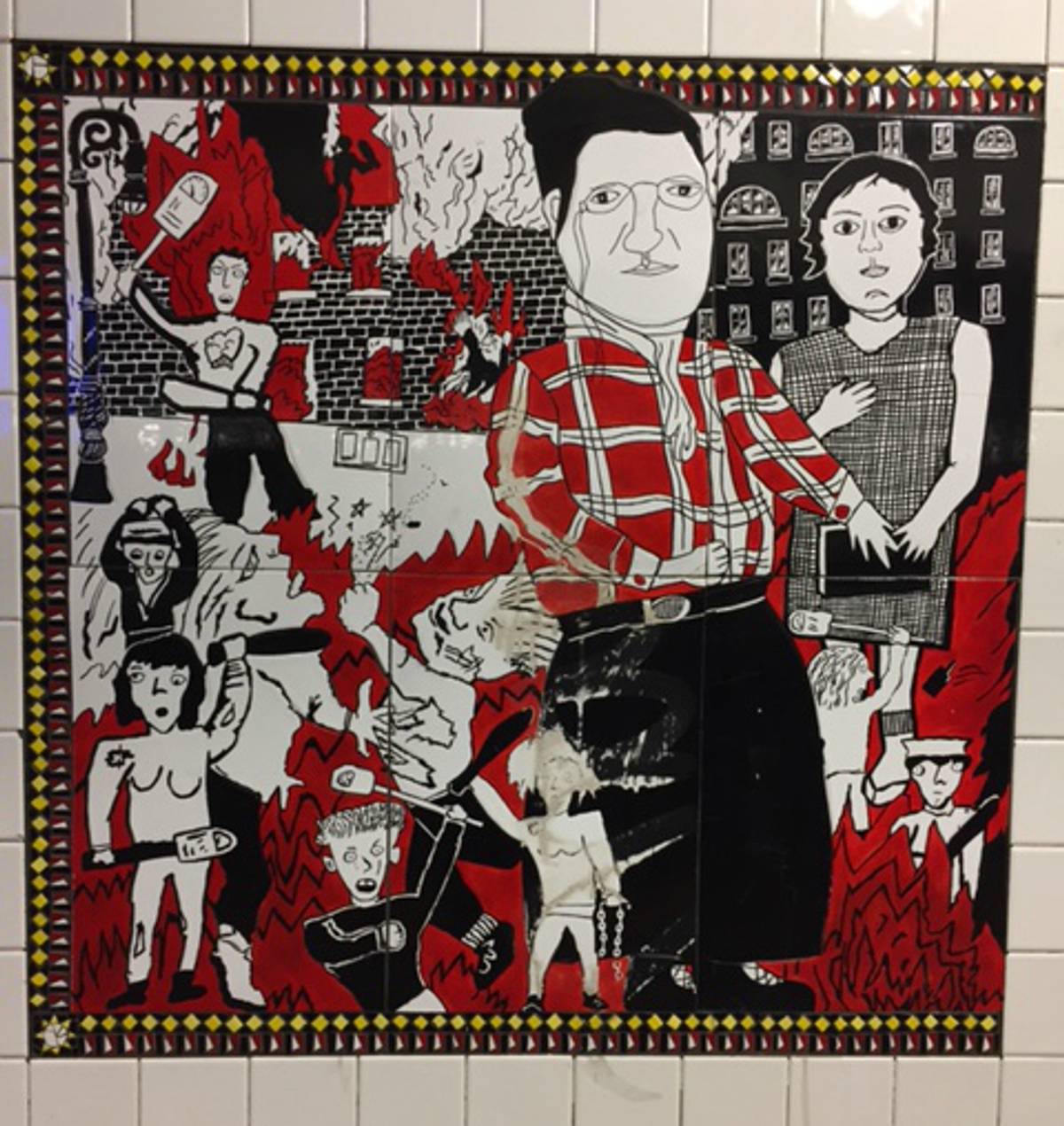

You may not know his name or even recognize his face, but if you’ve ever taken the New York City subway to the Christopher Street/Sheridan Square stop, you, and millions of others, know his art. Made up of 12 mosaic panels, Lee Brozgol’s “Greenwich Village Murals,” created in 1994 in conjunction with the children of PS 41, portray the bohemians, providers, anarchists, pacifists, feminists, communists, insurgents, and visionaries who represent the history of Greenwich Village. Their appeal today feels as relevant as ever.

Brozgol’s work has deep roots in American culture—gritty, political art that offers a scathing, profound, and heartbreaking look at our country. He recently exhibited a collection palimpsest masks in a show called “Six Chicks and a Dick” that featured, amongst others likenesses of Melania Trump, Dick Cheney, Kris Jenner. And, under the pseudonym, A. Lebowski, Brozgol is completing a 33-year portrait project, “Hidden America: An Artist’s Trip through the Personals” that chronicles the lives of one American from each state in the union.

I recently tracked him down on the Lower East Side of New York City and tried to peel back the layers.

PA: Of course they did! You’re from the Lower East Side?

LB: Born in Detroit. Family moved when I was nine to Chicago. I went to the University of Chicago and then I moved to New York.

PA: You’ve been living on the Lower East Side for a very long time?

LB: Longer than I care to say. First Fort Greene, then East 9th Street, then Crosby Street. When I lived on Crosby I had a very rich, very elegant, very glamorous aunt. She came down to visit me and the cab driver would not let her out. He said, “Lady, nobody lives here, I’m not letting you out.” She said, “No, no, no, my nephew lives here.” He said, “I’m going to take you to the corner. You call him and if he throws down the keys, I’ll let you up.’

PA: Where are your parents from?

LB: Dad is from Detroit and mom is from Chicago.

PA: Wow. So American.

LB: They’re both first-generation. On my dad’s side from Ukraine, on my mom’s from Lithuania. My mom’s dad was an artisan—a tinsmith. And my maternal grandmother was illiterate.

PA: You’re an artist and a social worker—can you take me back a bit?

LB: In the 1980s I was the Director of Foundation House, which was interim housing for formerly homeless people who were HIV-infected.

PA: That must have been insane.

LB: I felt very lucky when I came home and didn’t have to call the police.

PA: Why?

LB: Well, you would have to say to [a resident there], “No, you can’t have money to go home to go to your sister’s funeral because your sister didn’t really die. And they would get angry at you and throw chairs out the window.”

PA: It sounds very colorful.

LB: It was.

PA: Your most recent masks were inspired by a project you did in the ’90s, right?

LB: Yes, I made “death head masks” of 50 people on the right—George Bush, Jesse Helms, Alfonse D’Amato, William E. Dannemeyer, you get the idea. I got a call from a reporter who said he was with the New York Guardian—The National Guardian, at that time, was being sold on street corners in the Village and it was a very left-wing paper. I thought my people were calling me but the reporter was asking these hardball questions like, “You fabricated a deathhead mask of the president; do you think the president should be dead?” And I was like, “I think he’s dead in every way possible without physically being dead—he’s dead morally, emotionally.” And then the shit hit the fan. I wasn’t talking to who I thought I was talking to. I was talking to a very far-right-wing publication… They printed, “Artist Thinks President Bush Should Be dead.”

PA: That would land you in jail these days. In addition to the subway murals, you’ve done other public installations as well, correct?

LB: Two other public installations—Liberty High School on 18th Street and 8th Avenue, which is a high school for recently arrived immigrant kids. I worked with the students for one year to generate imagery about the immigrant experience.

PA: Wow. That’s incredible.

LB: It’s very interesting that we get to that today.

PA: And the other one?

LB: A stained glass atrium.

PA: Tell me a little about “Six Chicks and a Dick.” You honed in on very particular people, I’m interested in knowing what it is about them?

LB: It has to do with a feeling. Egocentricity and self importance is a red flag for me. There is something enraging about the artificiality that you want to get beyond it. So they evoke something in me.

PA: And your “Hidden America” project?

LB: I write to people who place ads in personal columns and I invite their participation project in a portrait project, which is only done through letters. The whole idea is to arrive at a visual metaphor that represents them. My intention is to do one for every state in the union. I’ve been doing this for 33 years. I have completed 49 states.

PA: Where are you finding these personal ads?

LB: In the beginning I started out writing to mainstream publications and getting zilch replies because people thought it was kind of hinky. And then I started going to underground magazines, to a more dominatrix/action/swinger types because those people were already comfortable with having images of themselves out there. Sometimes they send photos, sometimes they don’t. It’s all written. We have a dialogue.

PA: Can you give me an example? A salacious one, just for fun.

LB: One of my favorites—I call her the mother of the project—was an ad for “Disciplinary action, male slaves wanted.” The photograph was a very tawdry black-and-white photo of her whipping someone. She was very matronly, made up with this ghastly makeup, like Dracula, with a fierce snarl. I asked her to send me photos of her ordinary self—what she looks like when she’s shopping for groceries. So she sent me a letter, which was in a scrawl, and the person who emerged from that letter was almost the opposite of the person in the personal ad. She was confused, disorganized. The little bits of history she gave me were fragmented but they were all tragic. This daughter is on heroin, this one was hit by a car, sometimes I want to kill myself. She sent me tapes. This lasted for two years. I became almost like her psychiatrist.

PA: You better hope these people don’t show up at your house.

LB: That’s why I used a P.O. Box and a pseudonym.

PA: Were there any Jews in Detroit in the ’40s when you were growing up?

LB: One of the stories my parents tell is when they were looking for their first apartment, the first question the landlady asked was, “Are you Jewish?” And when they said yes, the landlady said, “Sorry, the apartment is rented.” When I was born, we lived in a building that my uncle owned so the whole question of anti-Semitism wasn’t an issue.

PA: And what about growing up? Was there a community? Were you guys culturally or religiously affiliated?

LB: My grandfather on my mom’s side was a socialist. My grandmother was a Sabbath Jew. She would light candles and make a special meal on Fridays. I think both of my father’s parents were illiterate. My dad’s mom was about the house and the kids and that’s it and my grandfather was an auto worker. He had his Schnapps and no religious affiliation.

PA: Did you experience anti-Semitism as a kid in school?

LB: When we moved to Chicago, the grammar school I went to fed four local high schools. The Jews got special permits to go to high schools that were further away, so you had segregation. There were tensions that resulted in a really vicious fight. As a result of this, the Board of Ed. stopped it and I was in the second class that went to the traditionally non-Jewish school. In four years I only had one incident.

PA: Which is to say that there wasn’t that much that anti-Semitism in Chicago in the 1950s.

LB: How did you draw that conclusion? I had one incident but it was preceded by this was a serious fight. Jews lived in an enclave.

PA: So there was palpable anti-Semitism. You were just shielded from it because everyone lived together?

LB: That’s right. My mom talks about being chased home when she was a kid by the Polish kids. Only recently, since the election, my feelings about being a Jew have intensified. I’m not observant at all but I really feel very Jewish. I’m a Jew. That was never a question. My wife was the daughter of a rabbi, her mother is a rebbitzin and they take Judaism very seriously. I do not participate, but I am a Jew.

PA: What’s your favorite drink?

LB: Pepsi. No, Coke. It’s a toss-up.

PA: That’s very unusual. Most people are avowedly one or the other.

LB: I’m a switch hitter. What’s in my pocket? Is that the next question?

PA: Not yet. We’ll get there. How do you drink your coffee?

LB: One cup a day, in the morning, light and sweet. With cream. It has to be cream.

PA: How do you eat your eggs?

LB: Over medium.

PA: What’s your favorite Jewish holiday?

LB: That doesn’t resonate with me, though I’ve made menorahs and Seder plates. During the holidays, my wife goes to temple and I’m in the studio.

PA: And you make art.

LB: Exactly.

PA: Did you have a bar mitzvah?

LB: No, I refused. My parents hired a tutor. I didn’t like him, he had halitosis and I was repelled and I was noncompliant.

PA: That feels like a good term for you—non-compliant. Gefilte fish or lox?

LB: Lox.

PA: Favorite pair of shoes?

LB: None of them seem to fit recently.

PA: Five things in your bag?

LB: Something to draw or write with, something to draw or write on, and dental floss. That’s it.

Periel Aschenbrand, a comedian at heart, is the author of On My Kneesand The Only Bush I Trust Is My Own.