A Washington Nationals Fan Ponders the Age-Old Question: Are Sports Just?

And is that Job on first?

So here’s a question that’s bothered me in some form of another for nearly my entire life, but that as a Washington Nationals fan is especially bothersome this week, although it’s bothersome just about every other week, too: Are sports just? Meaning: Is the final score nothing but the semi-random endpoint of a series of obliquely connected events, or a deeper reflection of what teams, like, deserve? Let’s put some pressure on the word “deserve,” too. Does a team deserve to win because it’s better than the opposition, or does a team even deserve to win by virtue of the scoreboard, i.e. fact that it’s actually, you know, won? Or is the whole idea of a team “deserving” to win—the sense of an athletic performance possessing some mysterious intangible moral worth that exists apart from and even above the crude positivistic results of the contest itself—in fact a bullshit construct?

Certainly there are varieties of athletic competition that strive to achieve as complete a justice as is possible in this or any life. The heavenly Sanheddrin couldn’t devise more excellent a moral system than the Olympic swimming pool, wherein the elements are predictable and stable, and a Katie Ledecky-type demigod will almost always win by virtue of being better than the rest of her competition. But trust me, most sports don’t work that way. Like Katie Ledecky, I root for the Nationals.

DC teams don’t get to win things. After last Thursday night’s loss to the Chicago Cubs in game five of the National League Divisional Series, the city’s four professional clubs have failed to log even a league semifinal appearance since 1998, an astonishing run. Aside from civic loyalty, what sustains DC’s brotherhood of miserablism is the yet-unrealized possibility of payback against an unfair universe. We know we don’t deserve this pain (where’s the fun in any of this if we did somehow collectively deserve it?), so when the Wizards or Capitals or Nats or heaven help us, the Skins finally achieve ultimate glory, our victory will be greater and more important and frankly better than anyone else’s victory has ever been. The future DC sports title will be the ultimate metaphysical clap-back, sweet, succulent vengeance against the entire moral and cosmic edifice of sports itself. When Bryce Harper lifts the Commissioner’s Trophy next year, it will be a kiss-off of Jobian proportions, a sign that God has finally been shamed into blessing us.

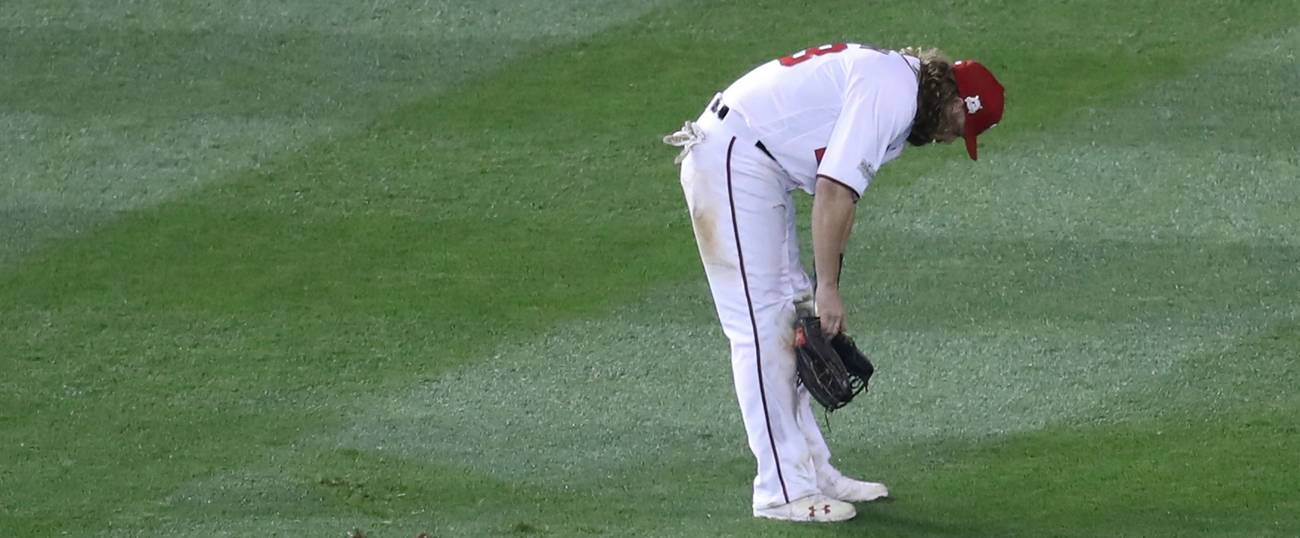

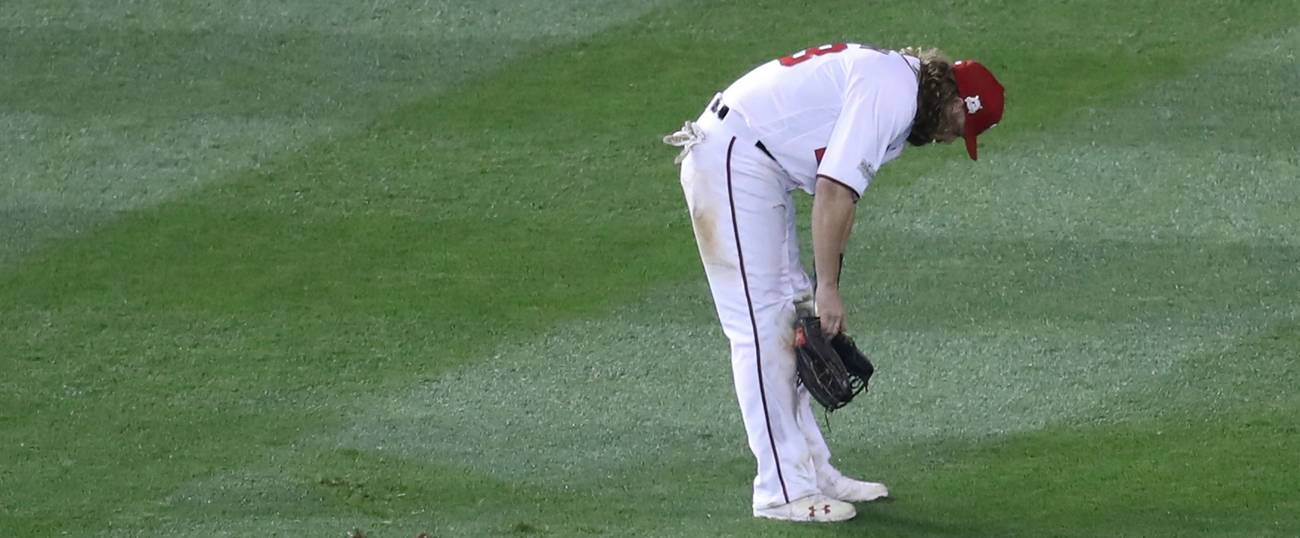

But what am I saying—There is no God; just check the box score. That fifth inning on Thursday night was a vision of chaos. Nats ace Max Scherzer, pitching out of the bullpen for the first time in four years, entered the contest with a 4-3 lead and dispatched the first two Cubs in under ten pitches. The ensuing series of events is unprecedented in the history of baseball. Wilson Contreras hit safely, as did Ben Zobrist. Addison Russell drove them both home on a double. Sucks, but then it gets weird: Nationals manager Dusty Baker intentionally walked Jason Hayward to get to the strikeout-prone Javy Baez. A passed-ball strike three on Baez sent Russell from second on to third, and an errant throw to first from catcher Matt Wieters sailed into right field, leaving Baez safe at first and Contreras at second while driving Russel the last 90 feet to paydirt. The Cubs led 6-4. Please ignore the special pleading of Nats fans who note that Baez clipped catcher Matt Wieters on his backswing and that the play therefore should have been called dead if we’re going by the absolute letter of the rules—the ball squeezed behind Weiters long before the bat lightly brushed him, and we, of all people, should know that a baseball diamond lacks the perfect justice of the swimming pool. Hey, there’s more! Catcher’s interference sent Tommy LaStella to first, sealing an immortal inning for Wieters and loading the bases so that Scherzer could bean John Jay and extend the Chicago lead to 7-4 a few pitches later. According to Baseball Reference, out of the 2.73 million major league half-innings in their database, none featured and intentional walk, catcher’s interference, safe-at-first on a strike-three passed ball, and a hit-by-pitch. Only on 22 occasions had three of those events occurred in a three-out span.

The Nats weren’t even done finding new and exotic ways lose baseball games, as there were still four innings remaining. The home team came within one run as the Cubs exhausted their bullpen, but a pivotal eighth inning rally ended when Jose Lobaton was called out on a two-out pickoff at first. This death sentence was issued after a lengthy video review that seemed perversely aimed at squeezing some fictive total certainty out of an event doomed to that insoluble state of vagueness for which the phrase “tie goes to the baserunner” was invented. Alas, a baseball diamond can sometimes be a swimming pool after all, at least where the Nats are concerned.

By what I promise is total coincidence, I had slowly been re-reading the book of Job the week of the Nats-Cubs series. By one prevalent interpretation, at the end of the book Job accepts his own smallness within God’s cosmos without accepting the essential justice of what he’s been through—this is one possible reading of the pivotal and cipher-like “dust and ashes” line in chapter 41. This time around, I’m convinced the most important pasuk of the book is actually the line directly before that one, where Job says: “By the hearing of the ear I’ve heard you, and now my eye has seen you.” (לְשֵֽׁמַע־אֹ֥זֶן שְׁמַעְתִּ֑יךָ וְ֜עַתָּ֗ה עֵינִ֥י רָאָֽתְךָ). This raises some interesting possibilities. In the Tanach, lots of folks get to hear the Lord speak, and some of them are real dolts. The most miserable man in history—someone whose misfortune resulted from a baroque divine conspiracy—is one of the very few to receive the awesome privilege of seeing the thing itself. That’s kind of encouraging, actually: There is a higher order, but that order isn’t necessarily just, and the cost of glimpsing it is one that no one should be willing to pay. No worries if you never see God; perhaps you’re better off without the trouble. And if you have had the misfortune of gazing upon the true inner workings of an ultimately absurd and arbitrary cosmic reality in which you nevertheless have the impossible and essential and paradoxical task of finding purpose and meaning, there’s succor for you as well, for the Lord blessed Job’s end more than his beginning. The Nationals’ 2018 season opens on March 29th in Cincinnati.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.