One Photographer’s Quest to Capture the Humans of Tel Aviv, One Snapshot at a Time

A late-comer to social media, Erez Kaganovitz became a Facebook sensation for training his lens on the people of his city

Two Black men, Zidan and Abdoul, pose in front of an image of two Africans rendered in graffiti on a cement Tel Aviv wall. “When people think about Africans, they usually have the notion that we are all like the graffiti figures behind us: Spear in one hand and a bone stuck to our head,” the men say. “We hope that, one day people, will see us the way we really are and not in a preconceived way.”

Although they represent one in a collage of thousands of images and stories Israeli photo journalist and artist Erez Kaganovitz has created as part of his ongoing project Humans of Tel Aviv, Zidan and Abdoul encapsulate its goal—for people to see the infinite possibilities of the human condition as provided by his lens and so change their perceptions.

Even before Kaganovitz and I sat down in a coffee shop on Chicago’s North Side, his eyes scoured the landscape of humanity around him. He was in the city as part of a lecture tour, but still on the hunt, and a cafe packed with late morning customers was abundant ground for faces and the stories behind them.

“Being a photographer you never really on vacation,” Kagnovitz said. “Because everywhere you go you see frames that you want to take pictures of. When you’re doing a project like Humans of Tel Aviv for so long it becomes like your second nature to start a conversation with total strangers.

He added that many of those conversations, although unplanned, have been meaningful. Indeed, dialogues across boundaries provided the genesis for Humans of Tel Aviv.

“When people hear about Israel, they usually hear about conflict, explosions, and war,” Kagnovitz said. “There aren’t a lot of headlines about how diverse Israel really is. I would travel the world and, when I told people I was from Israel, you could see how their facial expressions started to change. ‘Israel? Isn’t that the pace where people are getting [blown up] all the time?’ or ‘Aren’t you always in a perpetual war with your neighbors?’ I was really upset because, most of the people didn’t have a clue about the place I came from.”

As if it is something of which to be ashamed, he described himself as a “late-bloomer” to Facebook and admitted that “I didn’t understand why so many people were spending time on social media.” Yet it was within those confines that he found a photo project started in 2010 by fellow photographer Brandon Stanton to create an expanding document of the lives and faces belonging to the Humans of New York.

It was this project, and its over 500 peers, which helped Kagnanovitz perceive social media as a tool for a more idealistic desire to change expand the limitations of the acceptably shared vision of his home country.

Born and raised in Haifa, Kaganovitiz moved to Tel Aviv seven years ago, initially to take up roles in Israeli television news. He had lived among the city’s tremendously diverse population for two years when he was inspired by Stanton’s work to create Humans of Tel Aviv.

“I promised myself that I wasn’t going to pink-wash, white-wash, or sugar coat,” he said. “I wanted to show reality the way it is and let other people connect the dots for themselves.”

Thus, the home page of Humans of Tel Aviv eliminates the bland invulnerability of the selfie in favor of a candid and uncompromising tapestry weaved by the faces of over a thousand different people. These faces and backgrounds captured on camera or related in a brief narrative, slowly turn strangers who live outside of a friends list into the gift of understanding presented only to those who dare to look away from the safety of self and into the world presented by their eyes.

An older man presents the with the impish smile of a grandfather about to deliver a surprise gift to his beloved grandchildren. In the foreground, as if he is holding it up, is a set of bright orange beads.

“I was born in Iraq and, as a kid, I remember my father playing with the Masbaha,” Mordecai’s story reads, using the Arabic name for the beads. “Even though it’s used in the Muslim world as prayer beads, I used it to clear my mind. It’s a great tool for restarting your consciousness.”

In another image, a tattooed man in T-Shirt and jeans smokes a cigarette while sitting on a resplendent gold throne which wouldn’t be out of place in Trump Tower but which was instead placed outside of a pile of wood and a dirty wall.

“I didn’t go to the ballot box today because all the politicians are the same,” Asher says. “Once they claimed their throne in Parliament, they tend to forget the people who sent them.”

Both men are instantly relatable. Yet, to gain a foothold in the social media age, Kaganovitz ensures each image is uniquely presented to make people engage.

“Today, we are bombarded with so much information that you have to make something different,” he said. “I’m showing everything. I had a couple of stories about refugees who came from South Sudan and I got a little bit of criticism from people who wanted to know why I was publishing their stories. But showing the complexity of Israeli society gives the project credibility.”

Similarly, the results of Humans of Tel Aviv have defied even the expectation of its creator.

“They say that Tel Aviv is a bubble and that Tel Aviv is a state of its own,” Kagnovitz acknowledged. “Some Israelis joke that when you’re coming to Tel Aviv you should bring your passport with you when you’re entering the city. But, from doing this project for more than five years, I can tell you that Tel Aviv is actually a microcosmos of Israel: You can find ultra-Orthodox Jews, Muslims, and Christians alongside gay, lesbians, and transsexuals; refugees from Africa who fled to Israel alongside the posh people of Rothschild Boulevard. There is a representation of every social group from the Israeli society living in Tel Aviv, and they are all living side by side in a peaceful manner because of the ‘live and let live’ philosophy of Tel Avivians.”

As his work progressed, that philosophy slowly started to unfurl for Kagnovitz, and it was one he came to cherish.

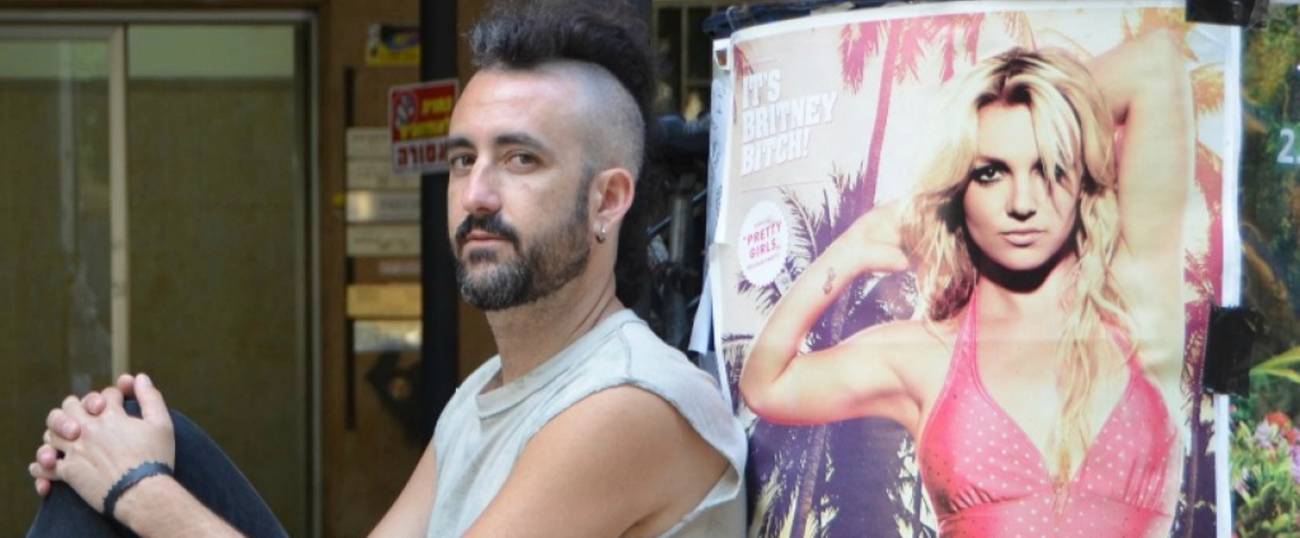

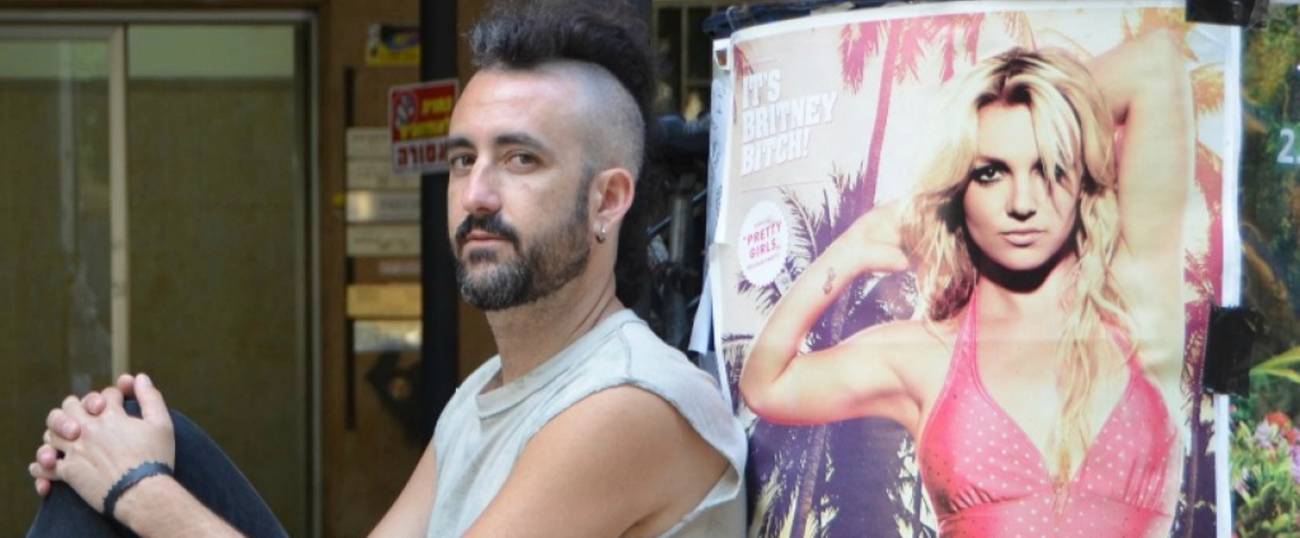

One of Kagnovitz’s subjects, Alon, replete with Mohawk and reclined against an advertisement of a scantily clad woman, refered to Tel Aviv as a “holy city.”

“I always wanted to be a sinner,” he said. “Among my sins, you’ll find eating pork and fetish and admiration for transsexuals. I don’t believe in heaven or hell because, where one man finds sin is where another man finds pleasure and joy.”

Agree or disagree, his face and opinions can’t be blocked with the ridiculous ease provided by social media. Maybe that’s why response to the project has been so visceral.

“I get a lot of messages, from tens of thousands of followers, in the Arab and Muslim world,” Kaganovitz noted. “They say ‘this is the first time we’ve seen Israel the way it is.’ I was so happy when I got those messages because people were actually engaging.”

To that end, Kaganovitz envisions a day when he can begin documenting the Humans of Tehran.

“It will give me an inside look into their society,” he said. “So, I can understand the way people are thinking and their culture.”

Ironically, Kaganovitz’s bottom line is as much in line with the perceived mission of social media platforms as it is about using them to eradicate the barriers those platforms create.

“It’s people to people,” he said.

Gretchen Rachel Hammond is an award-winning journalist and a full-time writer for Tablet Magazine.