Haman, the Magnificent Menace

Has there ever been a better bad guy?

Didn’t have time to read the Megillah this Purim? No worries! To celebrate the holiday, we asked five writers to reflect on the story’s five leading characters. Missed the previous installments? Click here to read about Ahasuerus; here to read about Vashti; here to read about Mordechai; and here to read about Esther.

An epic story is only ever as good as its bad guy. It’s why most of us lost interest in James Bond when the villains stopped being evil geniuses who launched nuclear weapons from secret lairs inside volcanoes and instead became tech billionaires who were willing to be just a bit more ruthless than, well, real-life tech billionaires. It’s also why the only Star Trek movie most of us remember fondly is the one featuring Ricardo Montalban as Khan, a genetically engineered maniac who dresses and behaves like outer space was one giant Burning Man gathering. It’s also why even those of us biblically impaired folks who can’t tell their Abinadabs from their Ahitubs adore the Book of Esther: Has there ever been a better baddie than Haman?

Put aside, for a moment, that whole nasty business about the genocide of the Jews, and Haman, c’est nous: Like a Shushanite Rodney Dangerfield, he can’t get no respect, always seeking validation and always feeling that whatever he’s got isn’t just quite enough. Which, if you think about it, isn’t entirely his fault: From the very first description of Ahasuerus’s opulent palace and decadent court, you realize that Shushan was an ancient Manhattan of sorts, a gilded town where people, to paraphrase the poet, knew the price of everything and the value of nothing. Can you really blame Haman for getting a bit woozy with his own success and going berserk when Mordechai reminded him that there were virtues in this world more precious than rubies?

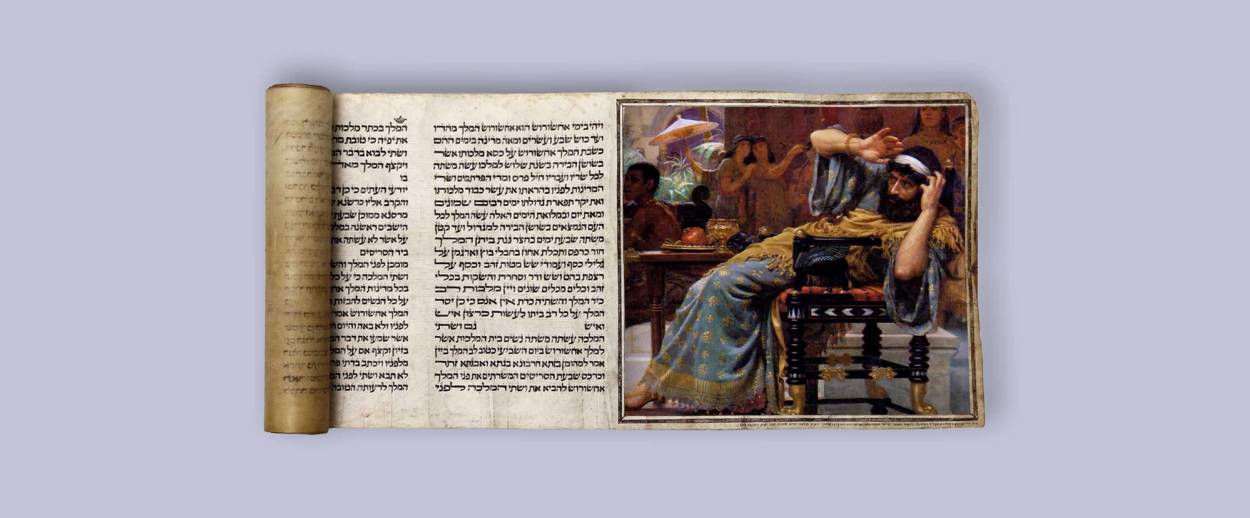

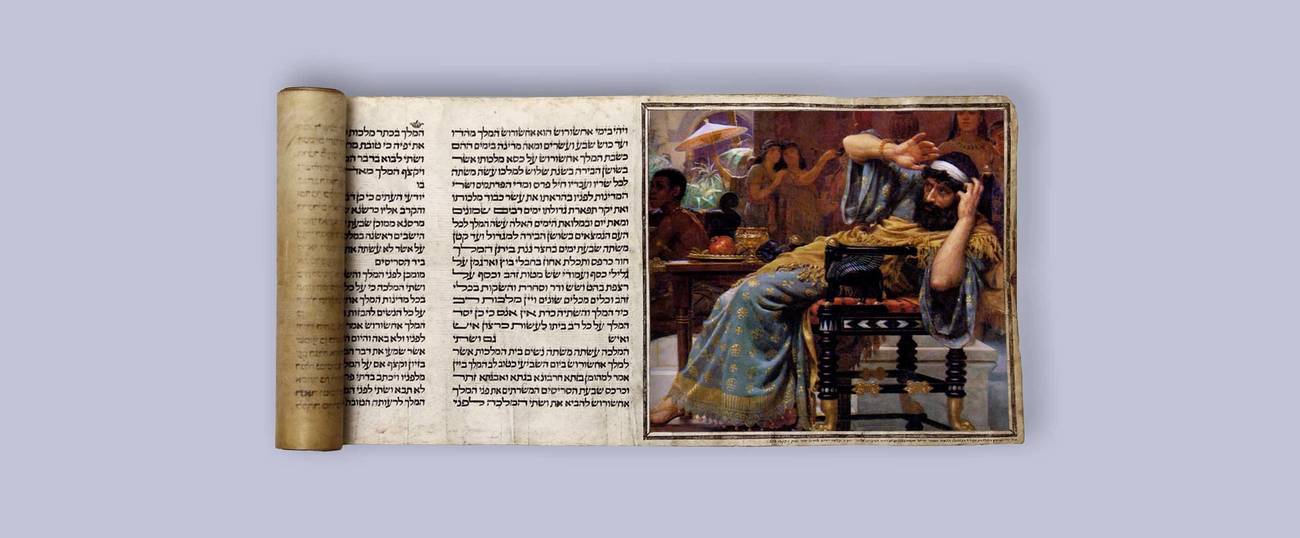

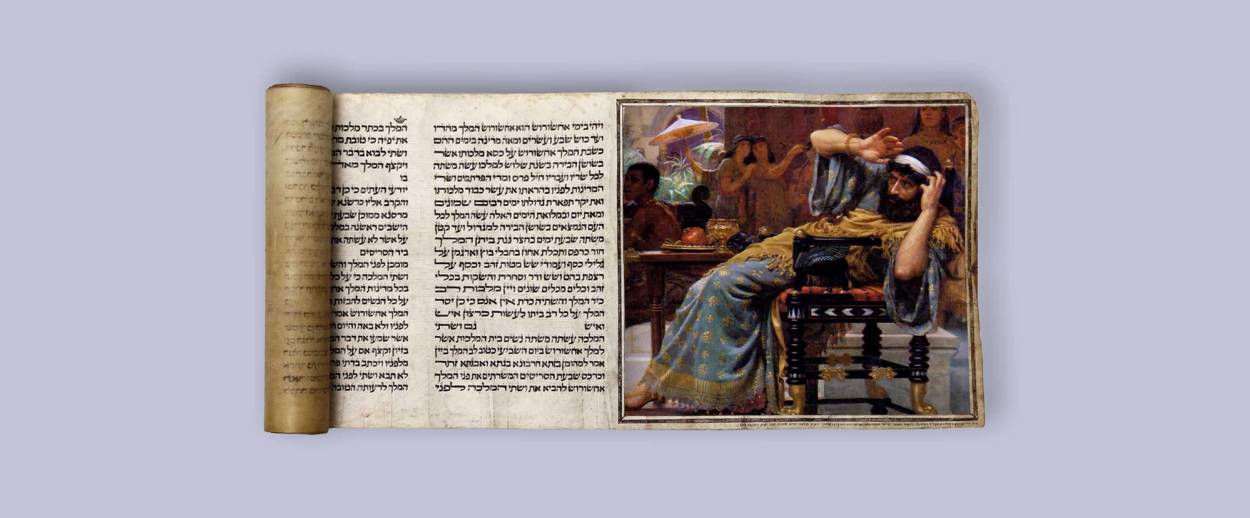

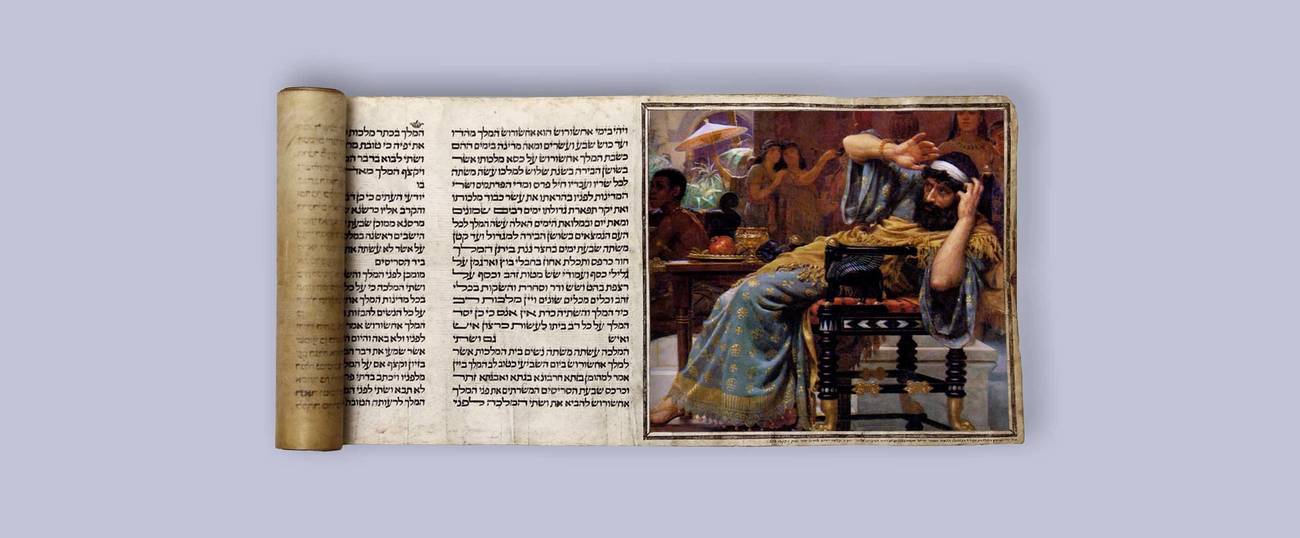

Not one to let his petty insecurities simmer, Haman goes big, deciding to rid himself not only of Mordechai but of all of Mordechai’s people as well. Then he goes home, and in a touchingly pathetic speech reminds his wife and his friends, as if they didn’t already know it, that he was a rich and powerful man. But watch Haman take to his evil work, and you see a cunning and capable man, first selling his plot to the king with a pro’s aptitude for politics and then casting lots to figure out precisely when’s the best day to strike against his enemies.

That last point sheds new light on the old villain. Why does Haman resort to games of chance to select the date of his genocide rather than just striking the Jews right then and there? It’s because Haman understands that his feud with the Jews isn’t really personal—it’s historical. He is, after all, the descendant of Agag, the Amalekite King. Agag was defeated in battle by King Saul, the mighty forefather of none other than Mordechai. Haman knows that his feud with his foe isn’t really his at all: It began long ago and will conclude long after he’s dead. With that in mind, he overcomes his bloodlust and lets fate run its course.

Thankfully, fate is never too kind to Haman. As the book draws to an end, he and his ten sons are killed and hung from a tree. And if, like Haman, you believe that the battle between the Jews and their enemies is an ever-recurring cycle, you may take some interest in knowing that in the early hours of October 16, 1946, ten men marched to the gallows in Nuremberg. There were supposed to be 11, but Herman Goering had killed himself hours earlier, so the ten remaining Nazis, like Haman’s ten sons, were led to the scaffold and hung. The last among them, Julius Streicher, went down kicking and screaming. As the noose was placed around his neck, he smiled ghoulishly and shouted “Purimfest 1946!” History, he knew, had just repeated itself, and, again, the bad guys lost.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.