Mississippi in Yiddish

The story of a hugely popular play about African Americans falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931 in Scottsboro, Alabama—that premiered in 1935 Warsaw

The greatest wickedness of our time is the relationship of white people to black people. ... There is a way to put it in Jewish terms: shfikhes domim, murder, literally, the spilling of blood. The white spills the blood of the black, not in one fell swoop, but drop by drop, with every gesture and every glance. When one is in America one often thinks to oneself that the heart of a black man must resemble a gaping wound.

These words, written by a journalist by the name Y. Gotlib, were inspired by a play called Mississippi, the most popular Yiddish play about race you’ve never heard of.

As New York’s theater scene lays dormant in the pandemic—and when once again, Black-Jewish relations feel strained, and while we process anew the traumas of African American history and, in this light, our country’s history—it feels like an apt moment to dust off what was once a veritable theater phenomenon that shrank into a small historical footnote: the crowded Yiddish theaters of pre-World War II Poland that showcased a play titled Mississippi. The play premiered on March 19, 1935, in Warsaw.

Mississippi was based on the experience of the Scottsboro Boys, nine African Americans falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931 in Scottsboro, Alabama. The Scottsboro Boys (ages 9 to 20) were initially sentenced to death but the case was retried numerous times throughout the 1930s, during which the Communist Party USA and the International Defense Alliance, (also communist) took on the defense of their case. By the time Mississippi was on the boards, the boys were still in prison after four years, even after their case had gained considerable international attention.

How did this case make its way to a makeshift Yiddish stage in Warsaw, alone among the stages in Europe, and all under the name of a different state from the one in which the travesty had occurred? In part, its origins are traceable to the months following WWI when a newly independent Poland signed the Paris Peace Treaty, promising to support its minority cultures and languages. While the new Polish government did not live up to its commitment to subsidize Yiddish-language culture, neither did it deny it its freedom. By the mid-1930s, Poland emerged as the preeminent incubator of engagé, avant-garde Yiddish theater, with Warsaw and its Jewish population of over 300,000 the theater’s capital.

The work of a man named Mikhl Vaykhert (1890–1967) and the institutions he built were a big reason for the theater’s achievements. Vaykhert was the head of Poland’s storied Yiddish Actors Union from 1925-27; author of a steady stream of what he called “theater criticism” (which he was careful to differentiate from theater reviews); founder and director of a studio that graduated several classes of actors from its rigorous three-year training program; a frequent hobnobber with Polish theater glitterati; and, finally, the creative director of Yung Teatr (Young Theater), what Vaykhert claimed was the only true experimental theater active in the Yiddish world.

Before returning to a newly independent Poland, Vaykhert had amassed considerable intellectual bona fides. Born in 1890 in Ukraine, he attended Polish gymnasium while studying Hebrew and religious studies privately. While working toward his doctorate in jurisprudence (which he received in 1916 in Vienna), Vaykhert also apprenticed with a Viennese theater director and then studied at Max Reinhardt’s celebrated theater school in Berlin. He arrived in Poland in 1917 eager to apply all he had learned to the Yiddish theater world.

When his studio began staging works publicly in the early 1930s, Vaykhert divided his repertoire between original Yiddish works (either older, canonical works or contemporary ones) and translations into Yiddish, often ones that reflected his leftist-activist agenda. The latter provoked the government to shutter his productions on occasion or its censor to withhold necessary “concessions” or permits. Vaykhert’s network of connections in the world of the Polish intelligentsia often helped him to navigate such hurdles. By 1933, however, Vaykhert was forced to operate under the pseudonym Michał Brandt in order to evade closure. Similarly, he called the play Mississippi instead of Alabama to evade the censors who were on guard for pro-Communist buzzwords, including those relating to the Scottsboro Boys.

When I first came across archival artifacts from productions of Mississippi—posters, tickets, and programs are tucked away in boxes at the YIVO Institute and will soon be digitized and accessible via the web—I assumed that the Yiddish production was a translation. I had come across ephemera of so many translations from this era: a review of the Vilna Troupe’s 1924 version of Eugene O’Neill’s expressionist play All God’s Chillun Got Wings (Shvartse geto), for example, and a poster of Ida Kaminska’s all-female production of Maria Morizowicz-Szczepjowska’s radical feminist We Women (1932). Directors saw translation as a way to introduce worldliness and sophistication to the Yiddish theater, and to engage with current social and political issues. In published interviews, directors wondered aloud: Why did the content of a Yiddish play need to focus on the “Jewish street”?

Mississippi was neither translation nor adaptation but conceived of and penned in Yiddish. Vaykhert thought of the Scottsboro Boys as subject matter with Leyb Malakh (né Leyb Zaltsman, 1894-1936), an established Yiddish playwright by the time of their meeting in 1933. Raised by his grandfather, a rabbinical judge, Malakh began writing after arriving in Warsaw from his native shtetl at the age of 16. Malakh recounts in an essay he published in the Warsaw magazine Literarishe Bleter that the topic lodged in his head since his trip to the United States:

I itched to write something with a social theme. ... Having just been [in America], I had attempted to represent in dramatic form a tragic event, the incident of Scottsboro. The tragic lynch-sentence of nine black boys. The event is well known to everyone. But the living drama is so big, that my first attempts at capturing it struck me as lifeless. ... But seeing the youth of Yung Teatr ... brought the Scottsboro tragedy back to my head.

By 1933 Vaykhert was equally enthralled by the Scottsboro trials, spurred, in part, by the attention it had attracted, from writers and artists. In Europe, the Scottsboro Boys had become a focal point of anti-American sentiment on the part of communist agitators; the string of injustices inflicted so publicly on the Scottsboro Boys all but confirmed the sanity of the communist cause. For many, the unwillingness of more mainstream political organizations to match the outrage on the left was itself outrageous.

The Scottsboro affair was an apt illustration of the struggles of the working class (more than, say, race) as the Depression and its epidemic of joblessness created the economic circumstances of the boys’ arrest. Malakh explores this in Act 1. A rather long first act takes place in a moving freight car where the seven African American young men and boys (Malakh reduced the number of boys from nine to seven) get to know each other as they travel between Chattanooga and Memphis, revealing their backstories to the audience. It is 1931, and they sneak on and off a slow-moving freight train looking for day work. Tensions rise after the conductor (not knowing about the presence of Black stowaways) sneak two white women into the same boxcar. They rise all the more when, a few stops later, two white men enter the car. The white men get into a fistfight with one of the African American boys who throws them off the train. When the train reaches its final stop, an angry lynch mob is surrounding the boxcar and the sheriff reveals that the white men had called the station accusing the boys inside of raping the women. The sheriff can only barely restrain the mob as it cries: “Pull them out! Lynch the devils!” As later scenes imply, the women corroborate the white men’s stories until after a trial that puts all the boys and men on death row when one of the women retracts her statement.

While it raises the banner of class conflict, the play also shows racism in different forms and from different angles. In one scene, for instance, members of the racist lily-white movement lavish gifts and sympathy on the boys’ female accusers, and in another scene one of the boys in prison recalls the ugly racist chant of the Ku Klux Klan as he was forced to watch them set a man on fire. In bits of dialogue, the play clarifies the boys’ irreversibly tragic situation: “[I]f we are free,” says one of the Scottsboro Boys to the others and to their lawyer, “we will be lynched or we will always fear being lynched.” Now that they have been accused, they realize that they are safer in jail. Another scene sheds light on the social reverberations of this tragedy: A woman calls over an African American boy to shine her shoes on the streets of New York. He can’t, he replies, as he doesn’t want to be accused of rape.

The play goes far in humanizing its subject and infusing the play with what its producers imagined as authentic African American culture. One character, for instance, is a former decorated soldier in the American war against Nicaragua’s Sandinistas while another’s life was shaped by the Great Migration of African Americans and now lives in Harlem.

The script is also embedded with an array of original Yiddish songs by the celebrated composer Henekh Kon (1890-1970) who composed songs in the African American musical tradition including jazz, gospel, and African American spirituals. One makes reference to the enslavement of African people, and another refers to the part former slaves took in the Union army fighting in the Civil War.

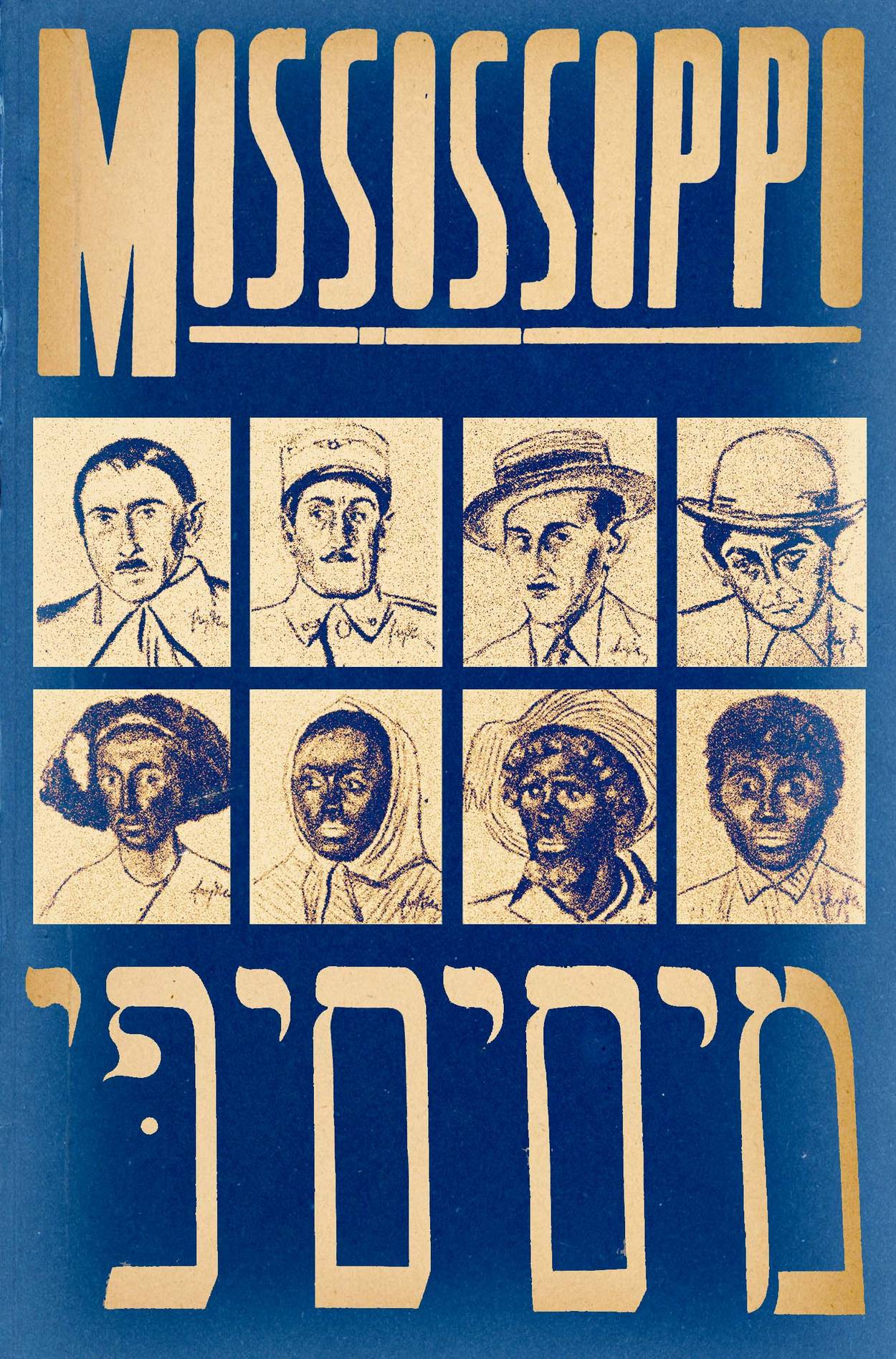

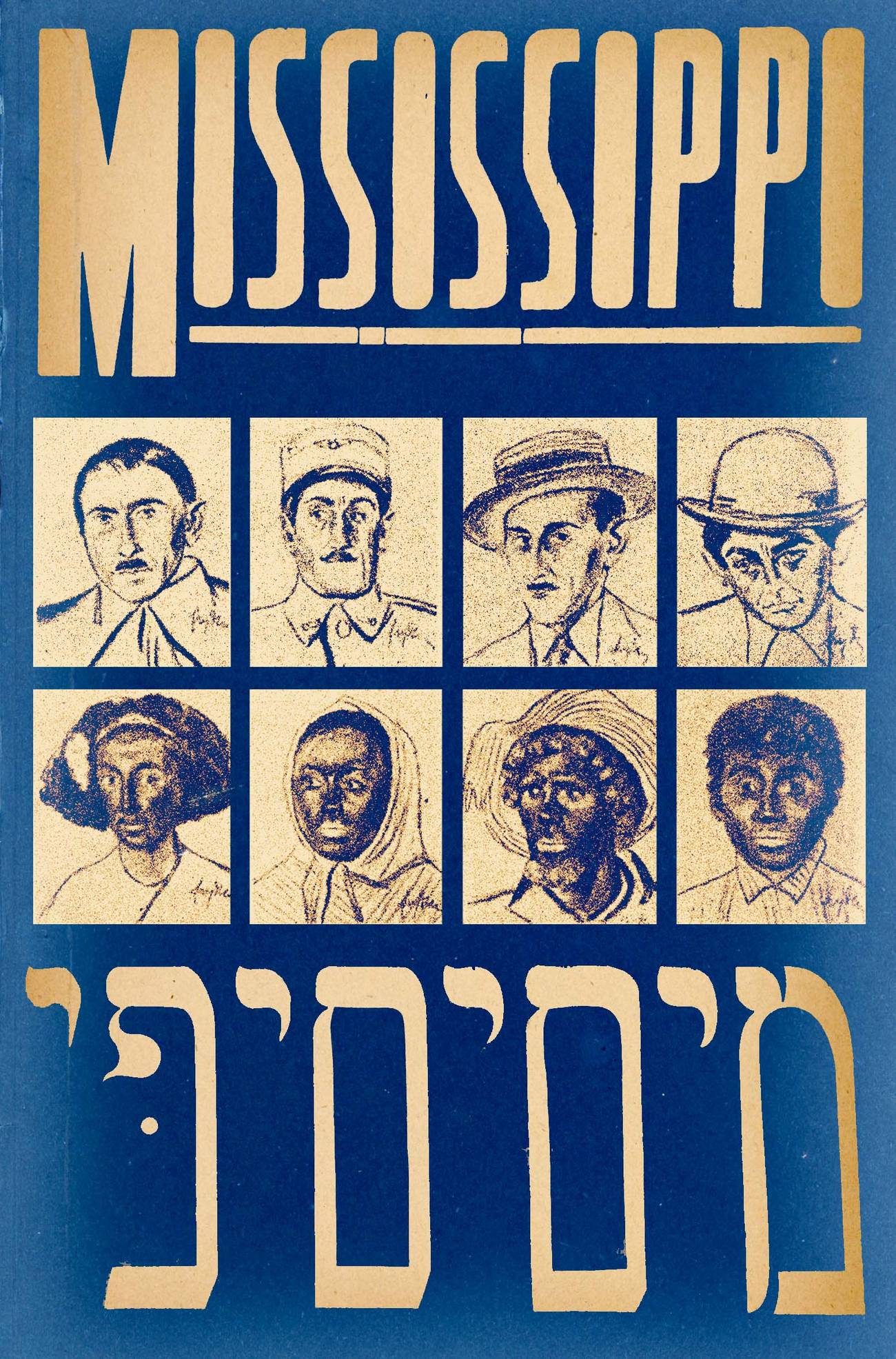

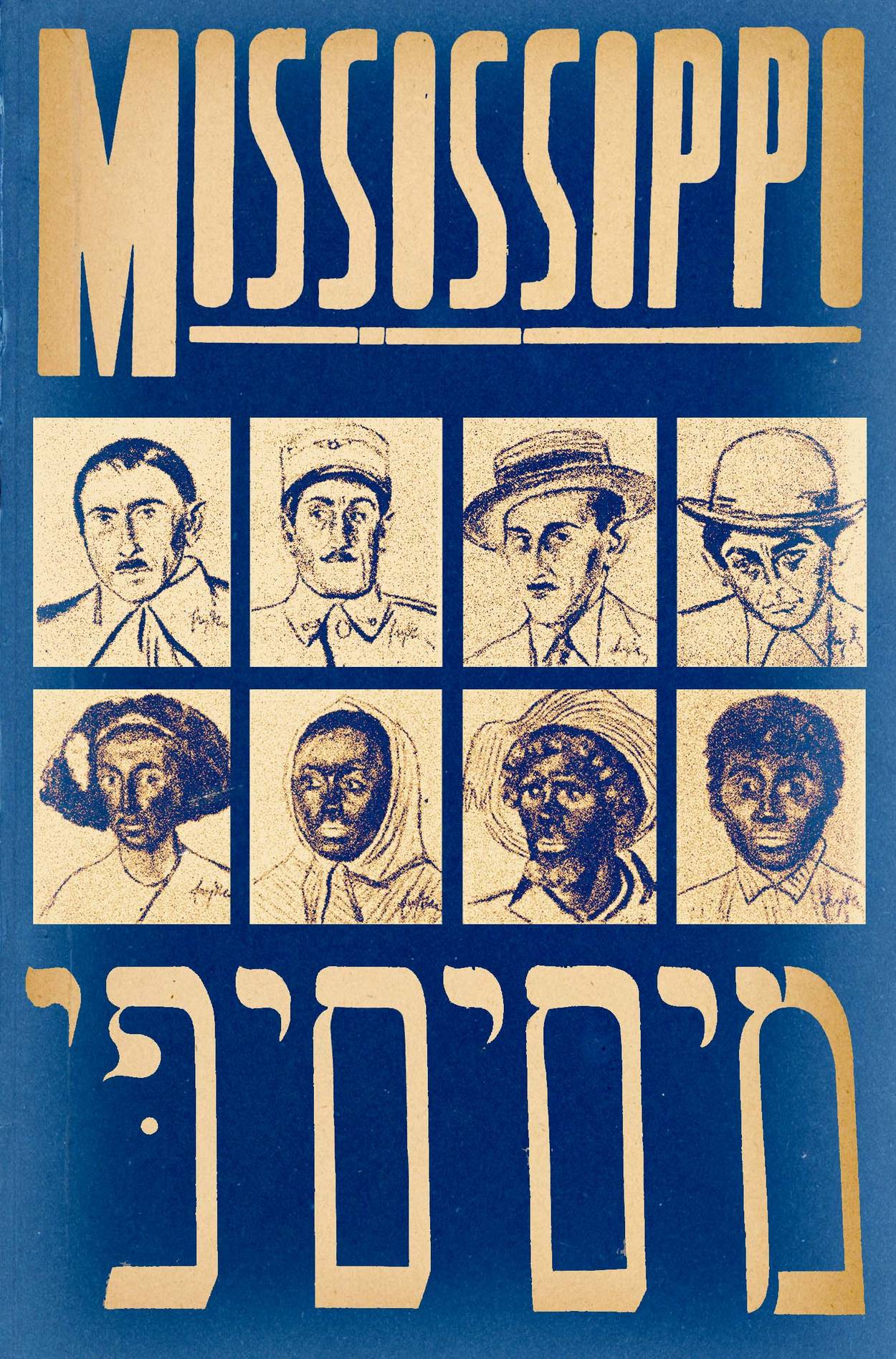

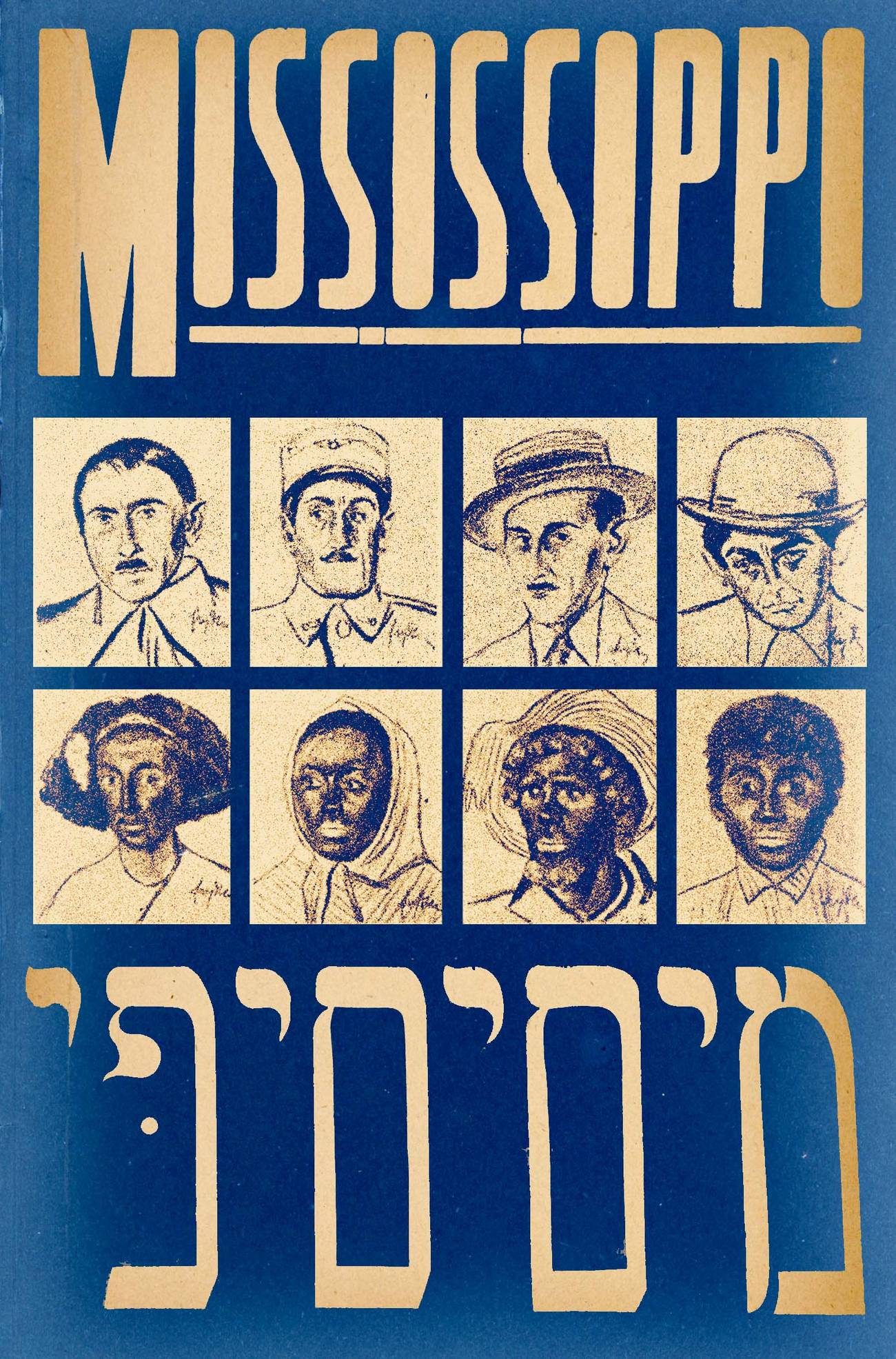

There are other aspects of the play that have not aged as well and, by today’s standards, might feel clichéd, examples of cultural appropriation, or worse. (The dated word “Negro” appears frequently, and racist characters use the N-word.) A cabaret singer in a Harlem nightclub sings a Yiddish-language song described in the script as “half jazz, half sentimental” that begins, “I am a brown Venus from Atlanta.” Actors wore black makeup with the clear objective to become their subjects and even, perhaps, to educate its mostly Jewish and Polish audience as to what an African American actually looks like. In this, the play hardly meets the standards of political correctness. According to the standards of its own day, however, it was very progressive; it strove for a sympathy with and curiosity about the texture and history of African American life.

Mississippi’s strong political point of view should not distract from how much it accomplished Vaykhert’s artistic and communitarian theatrical goals that informed all aspects of the production. Firstly, it was staged by a large ensemble cast: Thirty-five people are listed by name on the original poster. (On programs and posters, the cast is “segregated” according to the color of each of the character’s skin.) Vaykhert had a team of artists design a set so his production could be staged amid audience members. He was a keen observer of the biomechanics of Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874-1940) and Alexander Tairov (born Aleksandr Yakovlevich Korenblit, 1885-1950), Russian theoreticians of simultaneous theater—something that most resembles today’s environmental or immersive theater.

The set designer, the artist Władysław Zew Wajntraub (1891–1942), set up multiple stages throughout the space and spotlights directed the attention of the audience to the stage it needed to focus on—sometimes for only a line or two of dialogue before one spotlight went dark and another, trained on another stage, went on.

Malakh’s script reflects his knowledge of Vaykhert’s avant-garde staging and indicates each scene/stage with a letter. In one such series of scenes, for instance, “scene A” features the white girls (the boys’ accusers) in their apartment dancing to music on the radio; simultaneously, in “scene B,” (on a different stage) the sheriff visits the home of Katie (the mother of the youngest boy accused) first in the dark, and then, with spotlight, we hear the sheriff deliver the news of her son’s arrest. In yet a third scene, in the chapel of the prison, a priest oversees mass for the boys, first in the dark and then with light and volume. The simultaneous/near-simultaneous scenes highlight the indifference of the ladies; the heartbreak of the mother; and the hopelessness of the boys’ situation. These islands of staged theater in the audience, so the theory went, made the greatest demands on the powers of the audience’s empathy.

Initially, Vaykhert worried that his audience was not ready for his focus on African-American oppression:

At the time, I could not at all be sure that a story about negroes would find interest in a Jewish audience. It is a known psychological fact that an oppressed individual cannot harbor sympathy for a more oppressed individual (or class). ... at times he compensates for his own minority complex by soothing himself that there are those who are even lowlier (more oppressed), and, in contrast to him, he feels his life to be better ...

But Vaykhert’s worries were in vain. The play enjoyed a long run (about 200 performances), traveling to multiple cities throughout Poland for the two years following its Warsaw premiere.

Mississippi was also met by the Jewish press with enthusiasm and curiosity. In his review of the play, for instance, the journalist and Zionist activist Nosn Buksboym wrote a passionate review about how Malakh’s script leaves no stone unturned: It addresses the tragedy of the boys who at the time sat in prison on death row, it reveals the corruption of the justice system and, finally, it dramatizes what he refers to as the “privilege” of at least a part of the white working class that is blind to the deep brotherhood it shares with its fellow workers. The play was translated into Hebrew and published in Tel Aviv in 1937.

As the political situation in Poland darkened, reviews reflect close identification on the part of reviewers, like the 1937 Cracow production in the Polish Jewish newspaper Nowy Dziennik by Mojżesz Kanfer:

It’s no surprise that a Jewish author wrote [this] ... Aren’t Jews in many European countries these days just like blacks? Aren’t we fighting for the most primitive right to live? Then do not be surprised that the one who wrote a play about the tragic misery of American blacks is a Jew.

Just as Kanfer cannot help but see the plight of his fellow Jews in discussing Mississippi in 1937, it is hard not to wonder about the lives of its actors in the years that followed. Few are traceable. Yoysef Glikson (who played the role of the prosecutor) made it to the Soviet Union and, by chance, Kon (the composer) found himself in the United States before the war and also remained out of harm’s way. Pinye Ziglboym (the boys’ lawyer) was killed with his wife and child at Ponar (the killing field outside Vilnius) in June 1941. Dora Fein (who played one of the prostitutes) died of hunger in the Kovno Ghetto. Moyshe Shvaylekh (the sheriff) was in Pinsk when the Nazis invaded and somehow joined the underground Polish Army. Shvaylekh survived.

It is likely that a number of Mississippi’s actors were among those with the play’s set designer Wajntraub during the war. He led a paint shop in the Warsaw Ghetto that he thought would protect its workers from deportation and invited many actors to be among them. In the end, as the Ringelblum Archive documents, the Germans sent the entire staff of his shop to the ghetto’s station platform for deportation in a single day. A witness saw Wajntraub on the platform in tears apologizing to his workers for misguiding them, for leading them into the jaws of death.

Dora Fakel, (who played the role of Katie), might have been one of these actors. The celebrated theater and film director Jonas Turkov, who survived the Warsaw Ghetto and made it his mission to piece together the final days of his fellow actors in his book Extinguished Stars (Farloshene Shtern), mentions Fakel. He recounts that after Fakel was deported to the Poniatov concentration camp there was an attempt to rescue a group of actors including Fakel and to hide them on the Aryan side. The Germans caught them and sent them to Majdanek. There, they were shot on Nov. 3, 1943. Yung Teatr’s director Vaykhert survived, first in the Warsaw Ghetto. He was tried for war crimes in Poland following the war, a story for a different day.

No doubt, Mississippi’s success in the late 1930s worked off the energy of the Blacks’ and Jews’ common history of oppression. More remarkable, however, is the play as it reveals how much its Jewish participants, creators, and audience, mustered sympathy for this mostly unknown African American subject matter, for how and where they lived, the particulars of their persecution, and for their cultural forms and traditions. Ironically, these are the least palatable aspects of the play, at least according to our standards today. Even so, Mississippi endures as a model of empathic theater.

Alyssa Quint is associate editor at Tablet Magazine and author of The Rise of the Modern Yiddish Theater.