Sacred Space

Louis Kahn and the architecture of quiet reverence

Louis Kahn may be the best known Jewish American architect. Among practicing architects and critics he is certainly the most revered. Though not traditionally religious, nor affiliated with any synagogue, Kahn identified with being a Jew—in a way inevitable for almost any immigrant of his generation. Born in Estonia in 1901, he immigrated to America in 1905, and came of age in an era of opportunity and anti-Semitism. Like most Jewish architects of his generation, he received commissions from Jewish clients while much of his other work was in some way publicly sponsored, through government or universities.

In her valuable new book, Louis I. Kahn’s Jewish Architecture: Mikveh Israel and the Midcentury American Synagogue, Susan Solomon demonstrates that projects for Jewish institutional patrons were pivotal in Kahn’s architectural development. Many of his ideas about expressing spirituality through architectural space were honed in the process of designing and redesigning plans for Philadelphia’s Congregation Mikveh Israel, which he worked on between 1961 and 1972 and which, ultimately, was built by a different architect. Whether these developments were as dependent upon Jewish ideas, as Solomon suggests, is to me uncertain, especially as Kahn continued to develop similar forms in decidedly non-Jewish contexts. More important, though, is that these architectural strategies are so effective in a Jewish context as to create a fulfilling and convincing “Jewish space.” Ironically, while Kahn’s Jewish projects were at the very center of his creative oeuvre, in his lifetime (he died in 1974), few of Kahn’s Jewish clients embraced his vision, and even fewer built his proposed designs as he intended—or at all.

Three projects, the partially built Trenton Jewish Community Center, commonly known as the Trenton Bath House (which is actually in Ewing, New Jersey, and which Solomon has written about previously), and the unbuilt designs for Mikveh Israel and the Hurva Synagogue in Jerusalem (surprisingly not covered in this study), have survived as icons of modern architecture and subjects of scrutiny for several generations of architecture students. But while Kahn’s plans for Mikveh Israel were fairly well known throughout the 1960s, it has taken a long time for their influence to be felt in synagogue design. Using Kahn’s 11 year association with Mikveh Israel as the centerpiece of her study, Solomon investigates Kahn’s wrestling with the commission, the evolution of his larger ideas, and the practical means he developed to realize them.

Solomon presents a careful and very readable study of those designs, clearly connecting the congregation’s religious and communal needs with Kahn’s evolving vision. She demonstrates where Kahn’s concepts of site, space, light, landscape, and ritual continued to develop, often outpacing the congregation’s own ideas. In this, the book is an introduction to Kahn the architect and the idealist. Solomon also offers lengthy and informative excursions into post-World War II views of Jewish identity and community, and of the lively professional and public debate about the appropriate art and architecture for synagogues, and in a postscript muses on the state of contemporary synagogue design.

At the time he accepted Mikveh Israel’s commission, Kahn had built few buildings but was already a celebrated teacher, theorist, and planner. He had designed a simple synagogue in the 1930s, but his First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York (1961-63) gave a clearer indication of where his architectural direction. These were at odds with prevailing tastes in synagogue design. The contrast was starkly apparent at First Unitarian, which was directly across the street from Percival Goodman’s theatrical Beth El Synagogue (1961-63), which was being built at the same time.

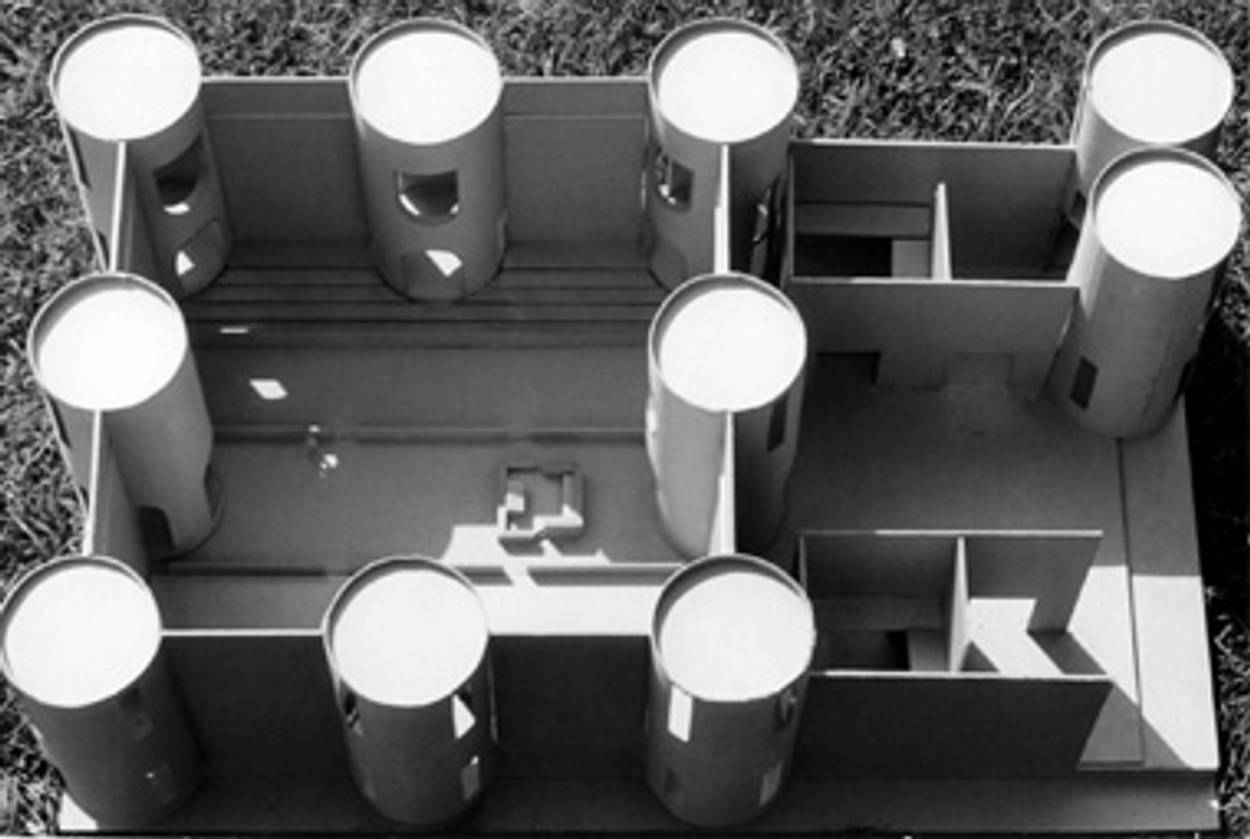

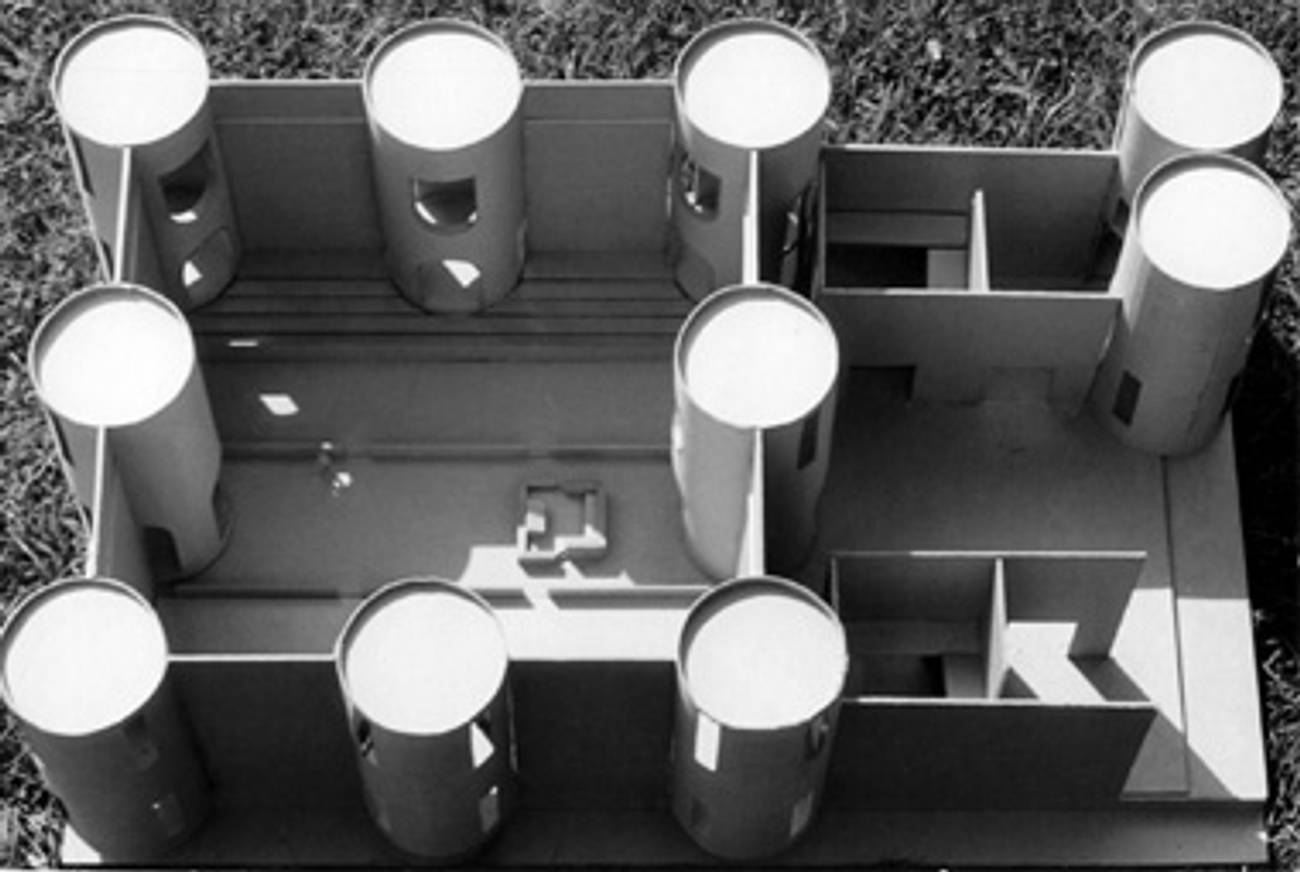

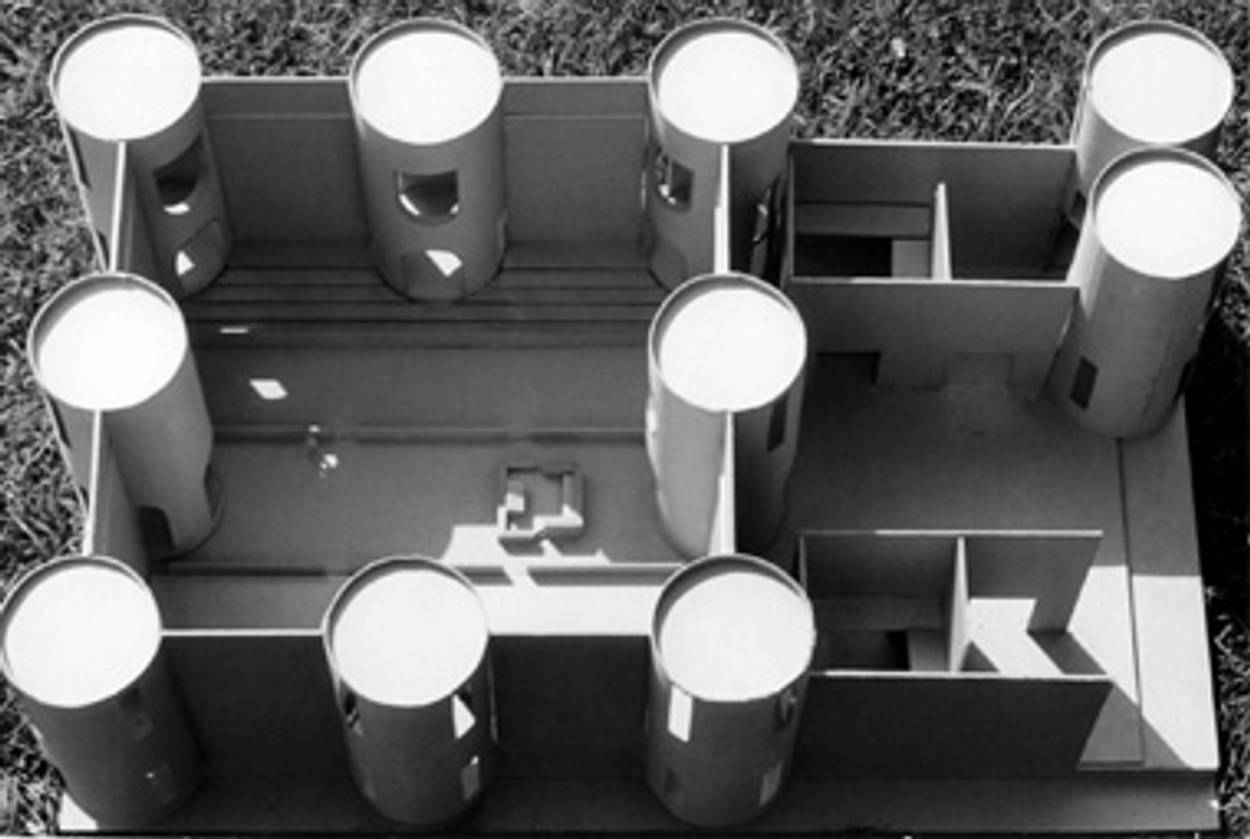

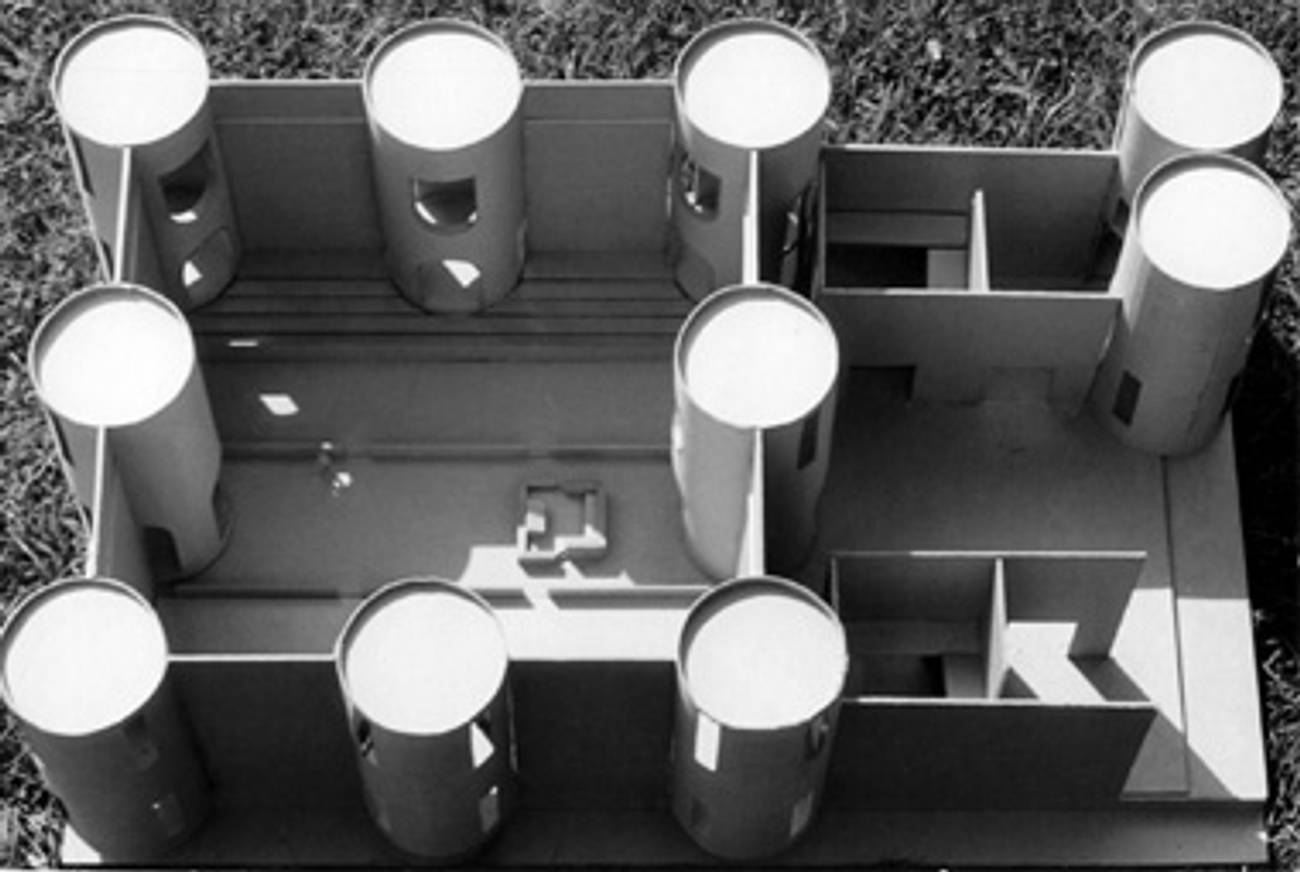

Unlike contemporaries who brought bravado expressionism and superficial symbolism to synagogue design, Kahn searched for, and achieved, something deeper. At Mikveh Israel he envisioned a concentrated sanctuary, simultaneously taut and calm, and lit by diffuse non-glare natural light filtered through “server” spaces of distinctive surrounding light towers. This approach was a reaction against the awe-inspiring effect of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Beth Sholom in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, (1953-1959) or Minoru Yamasaki’s North Shore Congregation Israel in Glencoe, Illinois, (1959-64). Those architects effectively used light for drama and symbolism. But instead of a strong light of revelation, Kahn preferred a diffuse light for reflection and contemplation.

That Kahn’s approach differed from the dominant movement in synagogue design is undeniable, but, initially at least, it was as much due to the nature of the commission as from any direction from Kahn. In some ways, the Mikveh Israel project should not be compared to many of the synagogues described by Solomon because it was so at odds with almost every other project of its time. Most congregations were building free-standing synagogue complexes outside of cities, and championed modernism as a forward-looking style. Mikveh Israel, however, was moving back into the central city, specifically to connect with (and exploit) its historic past.

Because the congregation wanted to access public support for its return to its site of origin, just off the newly-developed Independence Mall, the design had to be restrained and complement in style, massing, and materials the surrounding Colonial-era architecture. Kahn’s task was enormous—his aim was to reinvent modernism into something spiritual and humane, but his architectural vocabulary was restricted. The project was an anomaly—Orthodox, Sephardi, historic and urban—and the project was to house a museum. For many of these very reasons Kahn’s project was never realistic. The funds were never there when they were needed. In 1972 Kahn was fired as architect, and the congregation eventually used a different design.

Solomon writes that Kahn’s “plans had the possibility of producing an exceptional building, one that would have a lasting impact on synagogue design and American architecture. [Kahn] created a synagogue with a specific Jewish presence without adhering to the common symbols or decorative scheme that his peers demanded.” But because Mikveh Israel was never built to Kahn’s plan it has been the synagogues of Wright and Yamasaki (and also of Eric Mendelsohn and Percival Goodman to whom they were indebted) that have come to represent the architectural (and communal) aspirations of Post-World War II American Jewry.

In many ways Kahn (and his acolytes) are having the last laugh. Many of the flamboyant and celebrated synagogues of the 1950s and ’60s are being drastically renovated and even demolished. Meanwhile, some have called for finally building Kahn’s neglected design. Susan Solomon suggests a compromise: that congregations should reach out to young architects “to provide new models that will jolt synagogue design out of its current moribund state and follow Kahn in establishing creative ways to ‘be Jewish.’”

Samuel D. Gruber is director of the Jewish Heritage Research Center in Syracuse, New York. His books include American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community (Rizzoli, 2003).

Samuel D. Gruber, an architectural historian and cultural heritage consultant, is president of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments and author of American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community.

Samuel D. Gruber, an architectural historian and cultural heritage consultant, is president of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments and author of American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community.