Jewfro Visits Huck and Jim at the Whitney

A naked African-American, life-like young boys, personal property, public art, commerce, and cultural bravery collide at the nexus of the new West Side scene

Calvin Tomkins’ May 11 New Yorker profile of my old college professor, the sculptor Charles Ray, better known as Charley, details a public monument that the Whitney commissioned for the plaza of its new building, which opened last month. According to Tomkins’ article, they became overwhelmed by the sculpture’s two larger-than-life, nearly touching figures—a naked African-American man and a naked white teenager—and deeply concerned that the piece would offend “non-museumgoing visitors.”

In an effort to keep the polarizing and politically incorrect sculpture out of the public eye and away from the highly opinionated peanut gallery (of which I am a card-carrying member), the Whitney offered Charley numerous discreet locations other than the plaza. However, given the significant shift in context from public to private, Charley refused to compromise. Now, for better or worse, the sculpture sits unfinished in Charley’s Santa Monica studio, while Charley gains the reputation of being a “stubborn old white guy.”

After letting the dust in my head settle, I decided to go to the Whitney to observe the exact location where the sculpture would have stood. I was also eager to assess the exterior of the new building, which was designed by the major Italian architect Renzo Piano.

I arrived there. But I was disoriented. The once-gritty industrial region south of 14th Street on the far west side—known a decade ago for its meatpacking factories and gay bars (and fabulous late-night dive Florent)—had been fully transformed into yet another yuppified corporate village scene, lined with unaffordable restaurants and fashion boutiques. The main landmark is the High Line—the elevated freight-train track from another era that has been reincarnated as a cheerful tall-grass promenade, running through Chelsea’s art gallery district.

Everywhere I turned I saw people dining at quaint tables. They looked like those generic “pedestrians” that get collaged onto slick architectural renderings and presented to clients. Everyone seemed completely at home in a place that two days earlier was a fenced-off construction site populated exclusively by men in yellow hard hats.

The sun had gone down and the museum was closed, but the interior lights were still on. From across Gansevoort Street, I noticed a neon sign, radiating from the large plate-glass window of one of the upstairs galleries—a work by Glenn Ligon reading “negro sunshine.” Remember the rainbow-shaped “HELL YES!” sign that hung on the facade of the New Museum for all those years? Well, same effect.

And there was another even more prominent sign on a wall inside the lobby near the museum’s restaurant with the word “EAT” spelled out in big capital letters. A ubiquitous Robert Indiana. (I guess the artist must have given his permission to drop the work’s second word, “DIE.” Not so appetizing.)

Above the luminous transparent ground-floor, the building’s character flips into something entirely different. From afar, with its corrugated-looking facade, the asymmetrical, stacked-up boxes make me think of the aging industrial structures seen in the photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher—I’m picturing an old grain bunker standing tall on stilts over train tracks circa 1900. If the old Breuer Whitney came across as a fortress protecting art from the people—the new Piano Whitney seems to protect valuable property from rising waters.

***

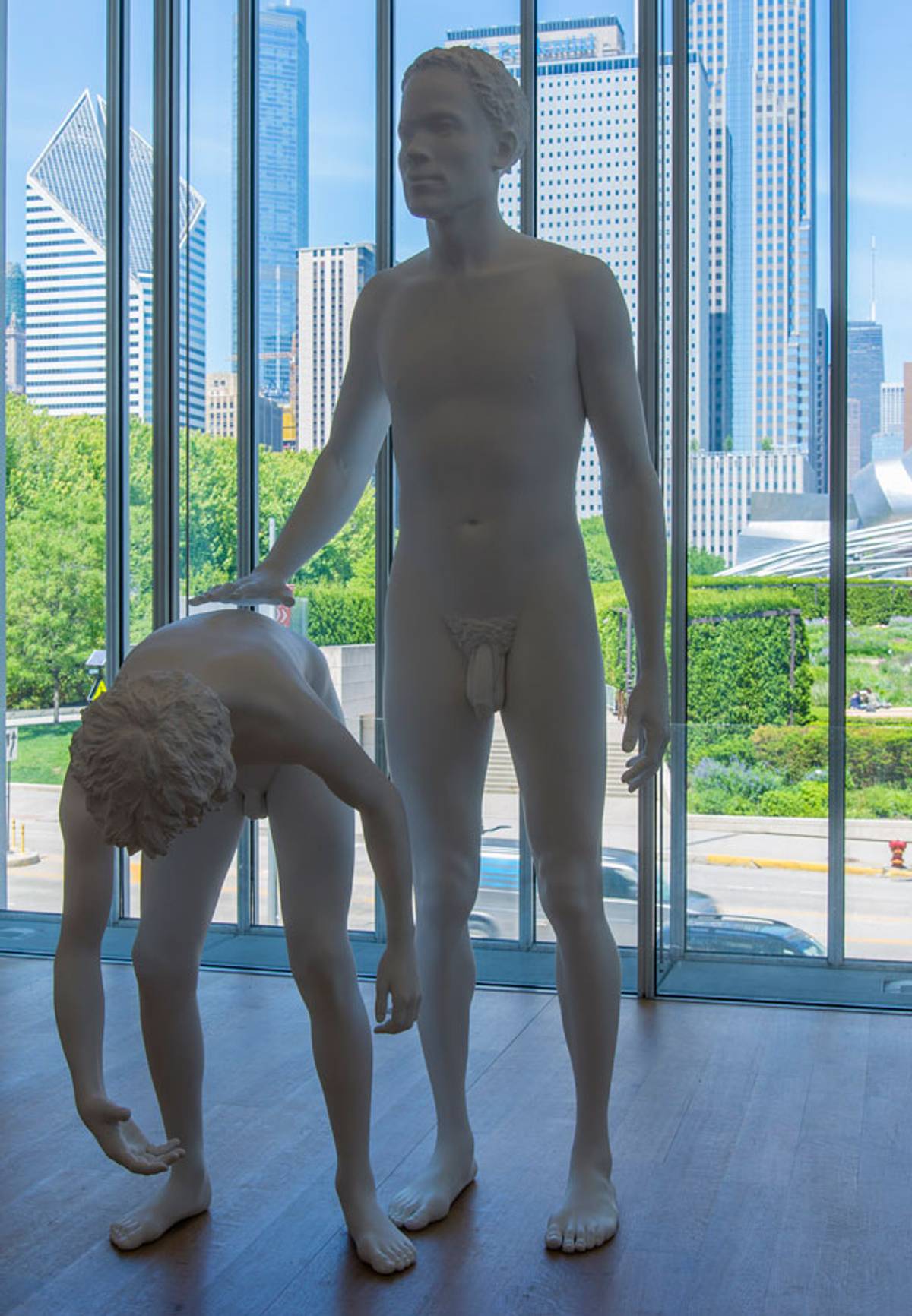

So, what caused the Whitney to get cold feet? Was it the sculpture itself? Let’s take a closer look at the two supersized naked bodies—Huck and Jim, we have been told—the legendary runaways in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Watson’s slave, Jim, stands tall, gazing off in the distance; he holds his hand, palm down (as if he is about to swear on the Holy Bible), a few inches over the back of the 14-year-old Huck, who is bent over reaching to scoop a handful of frogs’ eggs (so Charley says) from the river.

It’s hard to see the sculpture from a single photograph or to know what its stainless-steel mass would have felt like had it been experienced in three dimensions. Nevertheless, the power dynamic between the two isolated figures seems ambiguous from afar. Huck and Jim are positioned in close proximity on the verge of interaction, yet they are awkward and seem somewhat remote from one another.

Emphasis has been placed primarily on Huck’s reaching arm, while Jim stands back and to his side like a stiff column. Led by his curiosity, Huck’s body is off balance. In a yoga class, his pose would certainly require that the teacher come over and make an adjustment.

Huck’s extended arm bears an eerie resemblance to the arm of Marat, the murdered revolutionary who lies dead in his bathtub in Jacques-Louis David’s iconic Death of Marat (1793); or to the hanging arm in Caravaggio’s Entombment of Christ (1603-1604). It’s difficult not to see the figures as allegories that reference other artworks, back to the Renaissance.

But the reason the Whitney sensed controversy certainly has nothing to do with Huck’s gesture, but with a part of Jim’s anatomy: namely his penis, which is sizable and compositionally a little too close to Huck’s vulnerable rear end. It is on the verge of innuendo yet somehow resists being read as a sexualized image.

***

Yes, Charley can be a menace. Like Larry David, he is a creature of L.A. I was studying sculpture at UCLA in the early 1990s when I first met Charley, before his major retrospective at the Whitney; he was only just becoming front-page news. He came into my studio but ignored both me and my work and lumbered over to a messy table, where he started flipping through my scattered collection of CDs. He then mumbled something about having never listened to music before (hilarious), and he picked up a Ray Charles disk and began to examine it. “Hey, look,” he said, with a dumbfounded, spaced-out stoner expression, “this guy has the same name as me. But backwards.”

As Tomkins’ article points out in just about every paragraph, Charley can get close to his grad students. Back when I knew him, he would often employ us to do small jobs on his sailboat. I rode shotgun many times in his little Toyota pickup truck fearing for my life as he raced like a bat out of hell up the coastal highway toward a marina in Oxnard.

I actually learned something about sculpture as I observed Charley’s approach to “the art of sailboat maintenance.” If he needed to screw something in, we’d get back in the truck, drive all the way to the hardware store, and buy like one screw, and then get back to the boat and realize we didn’t have a screwdriver! So, we’d drive back to the hardware store and buy a screwdriver and return again to the boat. Finally we would complete the simple task, and while cleaning up, Charley would toss the screwdriver in the trashcan. What can I say? He’s not a “tool box” kind of guy. (Unless a toolbox happens to be featured in a sculpture. See his 1981 quasi performance/sculpture Shelf.)

Charley would pretend to be the grumpiest person in all of L.A., but he had the ability to charm and/or antagonize total strangers all day long (like, say, the woman in the hardware store who sold us the screw … and the screwdriver).

I also sailed with Charley. We set out in a thick fog one night to a mysterious “Hermit’s Island” somewhere out in the Pacific. I figured I was gonna die, which was fine, because Charley can make a young man feel safe to die—I assume this is the way a young Marine feels as he follows his older captain into heavy artillery. (Maybe this affect, or defect really, is something Charley learned during his formative years in military school.)

Studying sculpture with Charley was like being on the set of a Buster Keaton film. Always an elaborate chain of unanticipated events, each requiring a certain kind of creative ingenuity. Charley is like Buster Keaton, in a way. He has that same deadpan “stone face.”

I last came face-to-face with Charley in 2013 when he was in his Chelsea gallery, Matthew Marks, installing a work. It had been 15 years since I had studied, and driven, and sailed with him, and in all honesty he didn’t recognize me, sans Jewfro. He had aged and experienced years of success and fame. His eyebrows had grown like wings. He had gone through open-heart surgery and had even settled down and gotten married (not to a student).

At that moment, Charley was overseeing the installation of one of his sculptures, Sleeping Woman (2012). The figure is a woman who is conked out on a little bench at a bus stop. The woman (I have no idea if she was white or black, by the way, since she was immortalized in pure cut steel) is sort of half on and half off the bench. She is arguably one of the frumpiest, least idealized women ever to pose for a sculpture, and yet the work does not come across as a cruel joke; it is not a laughing matter. In my mind it has to do with Charley’s fundamental concern for the poetry of body language. And a kind of fluency in speaking this language.

***

While the sleeping woman converts a public spectacle witnessed outside into something extremely private, even intimate; Huck and Jim is exactly the opposite; it’s as if Charley wants to extract the two characters from the intimate pages of Twain’s book and thrust them forcefully into the physical world and into the public eye.

The fact that the two figures are literally outside and naked is integral to the work’s conception and inception—it was Mark Twain who disrobed them and stuck them on a raft in the middle of a river. In Tomkins’ New Yorker piece, Charley paraphrases from a scene in the book: “We had no use for clothes nohow,” he says imitating Huck’s vernacular, before clarifying that “Huck ran away,” and that “Jim was a runaway slave,” and that “They were outside.”

And so, the work was designed to be sans clothes and not inside the bounds of the museum, where it might fuel the same public debate originally intended by Twain, when he gave birth to Huck and Jim as a brilliant piece of satire.

But the question remains: How much debate is too much debate, especially in the age of social media? The Whitney might have become paranoid after the current battle in Washington, D.C., broke out over architect Frank Gehry’s extremely post-modern 40-million-dollar design for the Eisenhower Memorial, which will probably remain in political gridlock for some time. After it was leaked that Gehry was recruiting Charles Ray to contribute a sculpture of Ike in the buff, a smear campaign was immediately launched that identified Charley as “an artist whose work sexualizes children and is obscene.”

The museum had a similar choice as Huck, but unlike Huck they chickened out.

Or perhaps the museum feared the sort of uproar that occurred in the recent Whitney Biennial when it was discovered/publicized that a white male artist had mysteriously created, or authored, a fictional artist whose identity was that of a black female. Does the name Donelle Woolford ring a bell? Or the Whitney might have been intimidated by an unprecedented chat-room body-slam given to the white male poet Kenny Goldsmith, in reaction to an extremely provocative poem he read last month at Brown University. The poem was the complete Michael Brown autopsy report, which shockingly, and for no apparent reason, emphasized the victim’s private parts.

It’s not hard to see how Charley’s ultra-provocative and yet totally bland Huck and Jim could blow up, especially for those who are not familiar with, and would never want to be familiar with, his past work.

If you, hypothetically, do happen to know Charley’s past work, you would at the very least know that he has always dealt explicitly with male genitalia. In a recent steel sculpture shown at Matthew Marks, a naked barefoot boy crouches down and poses as if he is tying his shoe (Shoe Tie, 2012). One of the sculpture’s most compelling features is the honesty with which Charley articulates gravity’s effect on the boy’s scrotum. It is perhaps the most compositionally effective positioning of testicles in a sculpture that I have ever seen.

And there is an even better example in a sculpture from 1990 titled Male Mannequin—a generic, mannequin-esque, standing man with one peculiar feature: Fixed to the mannequin’s crotch is a life-like cast of Charley’s own genitals, with bushy pubic hair and all.

This being the case, even if Charley did endow Jim in the genitalia department, I’d hate to think that this detail—which is by no means insignificant but to my eyes is neither vulgar nor anatomically overwhelming—is what led the Whitney to be so Wimpy.

Charley is very well known for using scale to send a message, and when he tweaks scale he really tweaks scale. Consider his nifty doll-size Charles Ray assembled inside an empty wine bottle, just like a ship. Or his Tonka-esque hook-and-ladder blown up to the size of an actual fire engine, which was parked on Madison Avenue directly in front of the Whitney during the 1993 Biennial (a public artwork as rewarding as it is problematic, but also a piece of sculpture that sets out to occupy the liminal space between private and public).

In the New Yorker article, Charley makes an interesting comment to Tomkins while they stand at the Met observing an archaic Kouros figure from circa 590-580 B.C.E. “The testicles are full of life,” he points out. “I can project myself into the Kouros.” On another occasion described in Tomkins’ article, Charley stands before a Rodin on UCLA’s campus, relating to students on the abstract nature of the sculpture’s bronze toes: “If you look at the detail you can’t find realism anywhere,” he says. “The toes are misshapen. They’re full of human tension.”

Apparently, Charley believes that in a figurative sculpture a detail like a testicle or a toe is what leads the viewer—who may be from another time, even another millennium—to step into the intense realm of the sculpted being. The lesson I take from this is that there is a difference artistically between realism and “realizationism.”

It is this realizationism that leads me to wonder what effect Huck and Jim might have had had the piece been installed outside the Whitney bathing in—and in dialogue with—Glenn Ligon’s negro sunshine? While the caution of the Whitney may have nipped Charley’s threat in the bud, they certainly clipped an opportunity for some of us to feel a certain intensity.

Charley points out how Huck worries that by running away with Jim—by essentially helping him escape slavery—he’s actually stealing the property of Miss Watson. Here is the passage from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to which he is referring, spoken by Huck as he holds the letter he has just written to Miss Watson:

I was a-trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: “All right then, I’ll go to hell”—and tore it up. It was awful thoughts and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming.

So as we see, Huck has an intense revelation and basically decides, “Screw this idea of human property!” And as Charley points out, this is “a great American moment” in literature “and it still means something today.” Something that has to do not just with the ongoing narrative of civil rights, equality, and racism, but with an equally shameful issue at the core of art: the hoarding of private property.

As I see it, the museum had a similar choice as Huck, but unlike Huck they chickened out. In so doing, they may have missed the boat on a great American moment—where people inside and outside of the museum might have had a chance to metaphorically run away together, to coexist on the “raft” together, and to argue not about penis size or skin color, but about the stars.

In an interview done with the journalist Alex Israel for Purple in 2011, Charley spells out the exact philosophical argument he was likely hearing in his mind when he made his proposal to the Whitney. It’s “from chapter nineteen of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. It’s such a beautiful passage. Huck and Jim are on the river one night, looking up at the stars. Twain describes the river and the spacial quality around them. Jim and Huck are discussing whether the stars were made or just were. Huck thinks they just were. Jim says they were made. Huck thinks about it and says something like, ‘I once saw a frog laying eggs, so I reckon they could’ve been made.’ Have you ever seen a frog laying eggs? It’s like a billion eggs out the back of it … they leave a trail that looks like the Milky Way.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.