Before ‘The X-Files,’ There Was ‘Kolchak: The Night Stalker’

In 1974, the show that inspired Scully and Mulder delivered one of the most jarring depictions of anti-Semitic persecution ever broadcast on TV

Those who don’t remember the past are doomed to repeat it. Those who do remember it can watch it any time they want on YouTube. And because I’m the kind of guy who never forgets, especially when it comes to pop culture detritus, I found myself rewatching one of the most moving, jarring, and strange depictions of the Jewish predicament ever aired; even though it was originally broadcast in 1974, it felt menacingly fresh. If anything, the fact that it has maintained its jagged edge for more than four decades made it feel all the greater.

Called “Horror in the Heights,” the masterpiece in question is the 11th episode of Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Only 20 episodes were ever aired, but the show’s influence far surpassed its nasty, brutish, and short life on network TV: Among its writers were Robert Zemeckis and The Sopranos creator David Chase, both new to the craft, and generations of rabid fans went on to create their own tributes to Kolchak’s grimy and spooky universe. The most enthusiastic among them was a former editor of Surfing Magazine named Chris Carter, who, after securing a TV show of his own, delivered a strong homage to Kolchak and called it The X-Files. On last week’s episode—the show is currently on week four of a six-week miniseries revival—a character walked around dressed in a porkpie hat and a seersucker blazer, the iconic uniform of Kolchak’s eponymous hero and one of many tributes Carter has paid to his inspiration over the years.

What is it, then, about Kolchak that moved so many? And what is it that continues to rattle even today, when good frights abound in movies and on TV? For answers, turn off the lights and indulge in the aforementioned episode. In it, Carl Kolchak, the world-weary and charming Chicago investigative reporter played by Darren McGavin, is intrigued after an old Jewish man drops dead in the middle of an illicit Friday night poker game and his flesh vanishes soon thereafter. The cops shrug it off, suggesting that the victim had died of a heart attack and was unfortunately gnawed clean by hungry rats. It’s a grisly explanation, but it makes sense: The deceased was a night watchman at a treyf meat factory, not the sort of place that’s too particular about hygiene, and it’s not much of a stretch to imagine that having tired of rancid pork the rodents took advantage of the late watchman’s misfortune instead.

Kolchak, of course, disagrees. Being naturally inclined to believe that the most unnatural explanation is the likeliest—an obsession with the paranormal he passed on to his TV offspring, Special Agent Fox Mulder—he is convinced that the zayde died of something more sinister. When more elderly Jews are similarly chomped, he launches an inquiry.

What he finds won’t surprise you; any mildly experienced TV viewer would be able to piece together the clues provided during the show’s first few minutes and ascertain that the killer is a Rakshasa, an ancient Indian shape-shifting demon, and that the odd and wizened Indian man who’d suddenly settled in this exclusively Jewish neighborhood isn’t the killer but rather, being a lifelong demon hunter, the savior. None of that matters: As obvious as the episode’s plot may be, everything about it is profoundly disturbing.

For starters, the Jewish neighborhood feels a little bit too real, looking not like some sound stage facsimile of poverty but like anything you might’ve seen, circa 1974, in Chicago or New York or anywhere else where formerly Jewish neighborhoods, their affluent residents having decamped to the suburbs, were left to crumble with none but the feeble and the broke staying behind. As Phil Dyess-Nugent observed a few years back in the A.V. Club, the episode “derives its power from real-life terror, depicting a ghettoized class of senior citizens whose surroundings are so awful that people scarcely notice when something inhuman starts picking them off and munching on their flesh.”

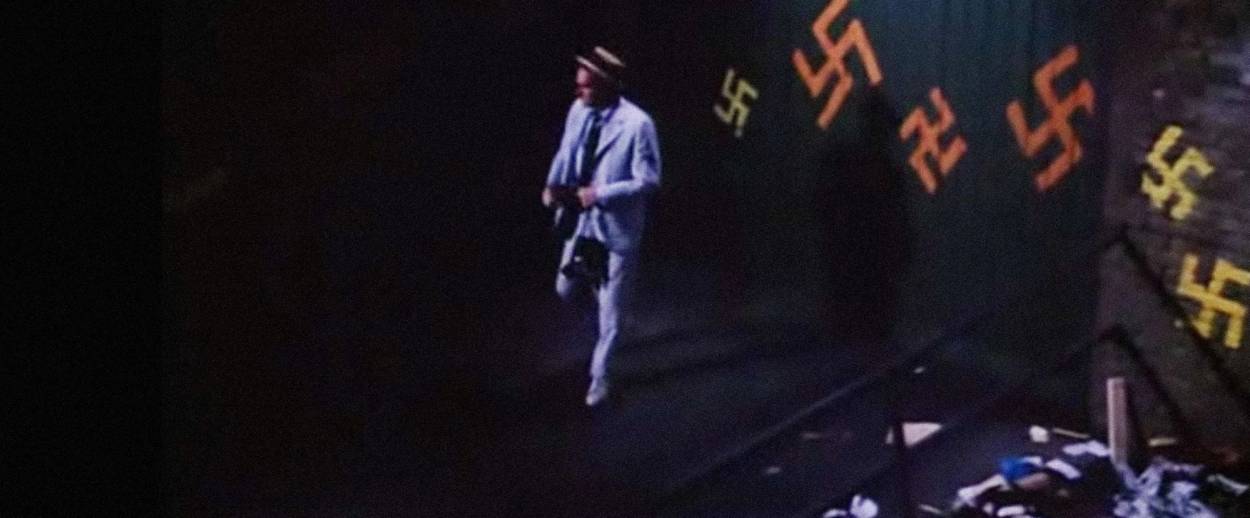

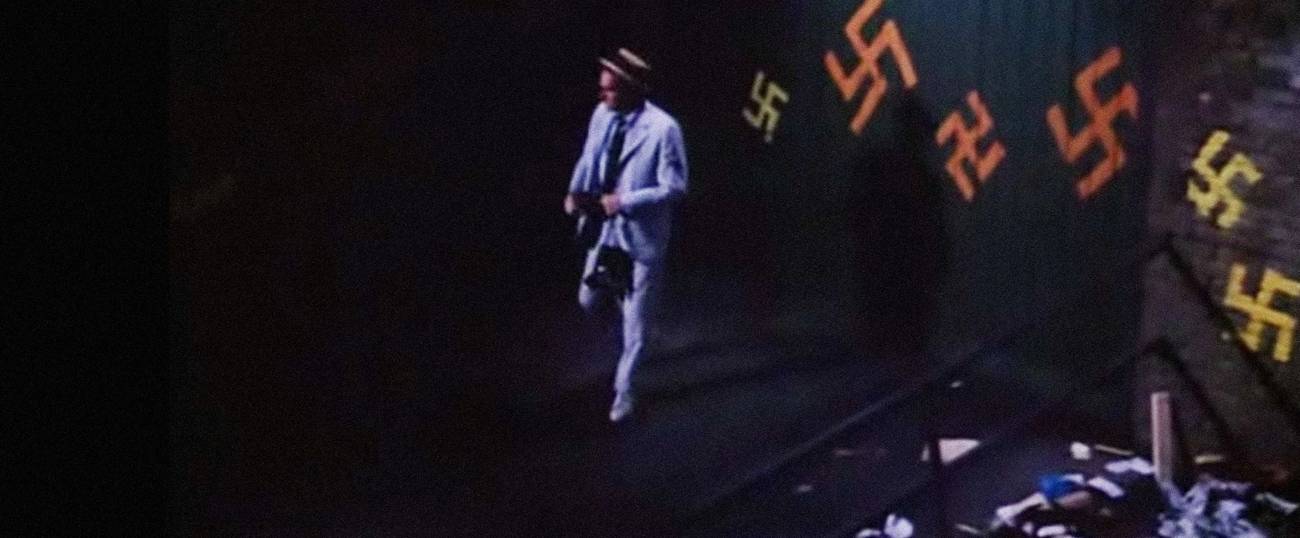

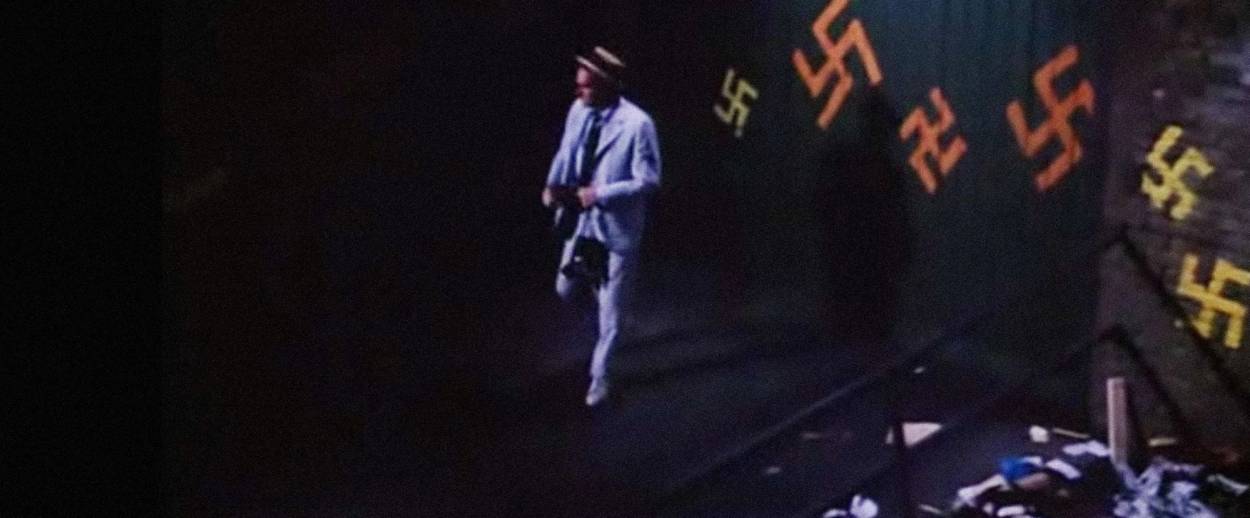

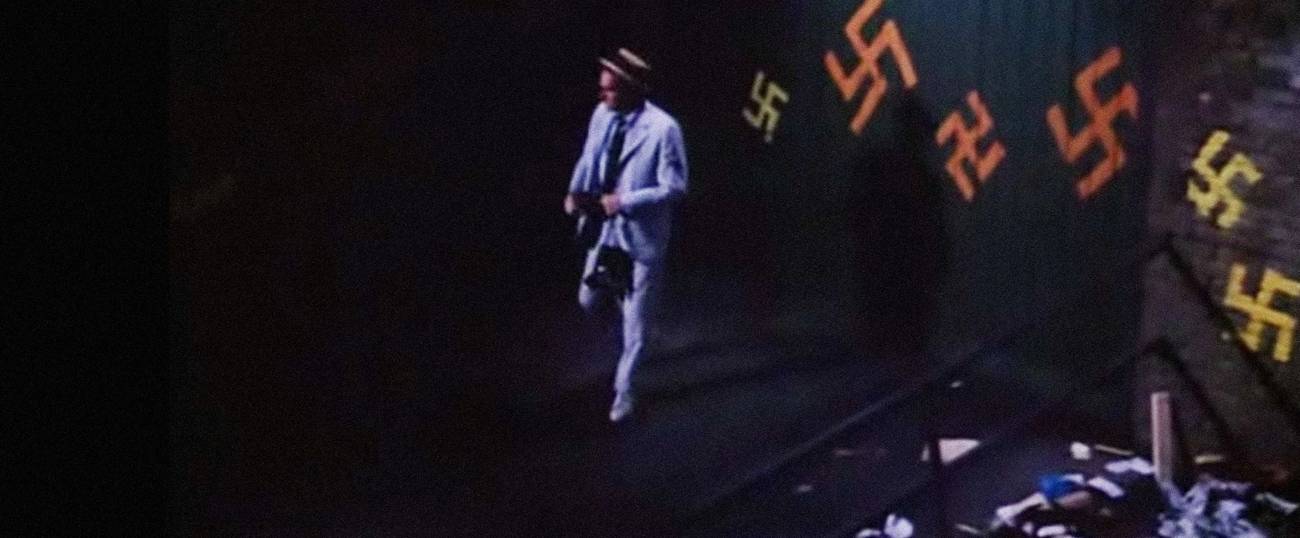

And then there are the swastikas. They’re not your ordinary works of vandalism. They’re large, regal, colorful, and ubiquitous, plastered above every appetizing shop, synagogue, or kosher butcher’s doorstep, in red and yellow and green and white. They are, Kolchak soon learns with his perennial, bemused who-knew expression, Hindu emblems predating the Nazis, but given the context—old Jews, likely survivors of the Holocaust, brutally murdered by a dark force—they’re terrifying nevertheless. And not in an ephemeral or symbolic way: While no Rakshasas, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, haunted Jews in America in the middle of the 20th century, Americans at large were hardly inclined to look at their Semitic neighbors as equals. In a wide-reaching surveyconducted a few years before Kolchak debuted, 46.6 percent of Americans said Jews were “more willing than others to use shady practices to get what they want,” and more than half claimed Jews “should stop complaining about what happened to them in Nazi Germany.” Among non-Jewish respondents, 43.4 percent replied that they’d “strongly” or “somewhat” object if their child wanted to marry a Jew who came from a good family and had a good education. Such sentiments are hardly occult, but sometimes the best way to grapple with great and debilitating and very real terrors is to recreate them as fictional boogeymen instead.

Because the show was made in the 1970s, when Americans could stomach candid discussions of touchy topics like race and religion without recoiling in horror and demanding that privileges be checked and safe spaces erected, Kolchak could approach such sublimation. And because “Horror in the Heights” was written by Jimmy Sangster—the brooding Welsh genius behind Dracula and The Curse of Frankenstein, both starring Christopher Lee as the monster—the sublimation is particularly neat. In Sangster’s reimagining of the Indian myth, the Rakshasa takes on the form of the person the victim trusts most; the first elderly Jew to get slain sees the monster as his rabbi, the second and third as a friendly police officer. It’s hard to think of a more effective—and more shattering—artistic representation of that core Jewish fear: the premonition that even your friendliest and most trusted neighbors could one day and with no apparent reason become your executioners.

With Jews shot in Brussels and Paris, stabbed in Jerusalem and in Tekoa, and assaulted in greater numbers than before in the United States, all that we’ve repressed for decades is returning. To quote another great elderly Jewish American who knows a thing or two about demons, it’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there. What cultural works will emerge from the darkness? Probably not more tales of appetites unchecked or shows about nothing or other expressions of domesticated anxiety. If Kolchak has taught us anything, it’s that the only things that go bump in the night are real monsters.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.