Thick-Sprinkled Bunting: Our Flag and Its Poet

What Walt Whitman can tell us about our democracy

The best new thing that has emerged from the political campaign is a novel way of displaying the flag, not as a lonely drooping banner but as a giant bouquet of innumerable flags spread across the stage, colors ablaze—the stars-and-stripes as a garden landscape, a shimmery ocean, a harvest glory, a voluptuous sunset. Was it Donald Trump who popularized these over-the-top displays? Possibly it was. He has the con-man’s knack for theatrics. But Hillary Clinton, too, has taken to standing in front of star-spangled multi-flag extravaganzas. Likewise President Barack Obama. And Justin Trudeau in Ottawa has outdone everyone else. He hosted a “three amigos” summit just now—himself, President Obama, and President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico—at which everyone denounced populist charlatans. Peña Nieto muttered darkly about Hitler and Mussolini. It was good. But best of all was the wild display of national flags—the red-white-and-blue, the red-and-white, the green-white-and-red—arrayed like a magic forest for the amigos to traverse on their way to the microphones, mythic heroes surrounded by undulating hues.

I have been reading Whitman on the American flag. He wrote about it repeatedly, though I think only during the years of the Civil War—years of ferocity and sorrow. Naturally his flags are living things. They sing, gaze, beckon, ripple, and pass by. The flag in “Song of the Banner at Daybreak” exhorts the poet himself to speak up: “Yet louder, higher, stronger, bard! yet farther, wider cleave!” The flag sings of the higher values—of more than wealth, and more than peace. Sometimes the flag is womanly. One of his war poems was a not-entirely successful ode to the flag called “Bathed in War’s Perfume,” which he never inserted into Leaves of Grass:

Bathed in war’s perfume—delicate flag!

O to hear you call the sailors and the soldiers! flag like a beautiful woman!

O to hear the tramp, tramp of a million answering men!

O the ships they arm with joy!

O to see you leap and beckon from the tall masts of ships!

O to see you peering down on the sailors on the decks!

Flag like the eyes of women.

But I think I know what he was getting at. You can see it in one of the other flag poems, “Delicate Cluster”:

Delicate cluster! flag of teeming life!

Covering all my lands—all my seashores lining!

Flag of death! (how I watched you through the smoke battle pressing!

How I heard you flap and rustle, cloth defiant!)

Flag cerulean—sunny flag, with the orbs of night dappled!

Ah my silvery beauty—ah my woolly white and crimson!

Ah to sing the song of you, my matron mighty!

My sacred one, my mother.

Death, for Whitman—death is a woman. That is what he means. Death is the all-welcoming and all-comforting mother.

Ultimately the flag, which is teeming with life, and is the flag of death, is the banner of the revolutionary cause. Everyone who has read Leaves of Grass will remember “Thick-Sprinkled Bunting”:

Long yet your road, fateful flag—long yet your road, and lined with bloody death,

For the prize I see at issue at last is the world.

He means that America is fighting for democracy’s conquest of the world—democracy, in universal battle against the other, enemy principle, which is the flag of kings. When he looks at the “flag of stars! thick-sprinkled bunting,” the vision fluttering before him is the “flag of man.” It is not the flag of a mere country in a mere corner of the earth. It is the flag of democratic liberty universally. It is the flag of human nature, long hidden but now, at last, revealed and even flourishing. And he sees in the flag the future history of the world, the long terrible struggle that awaits—the struggle against aristocracy and oppression and superstition. Was he wrong to see this future?

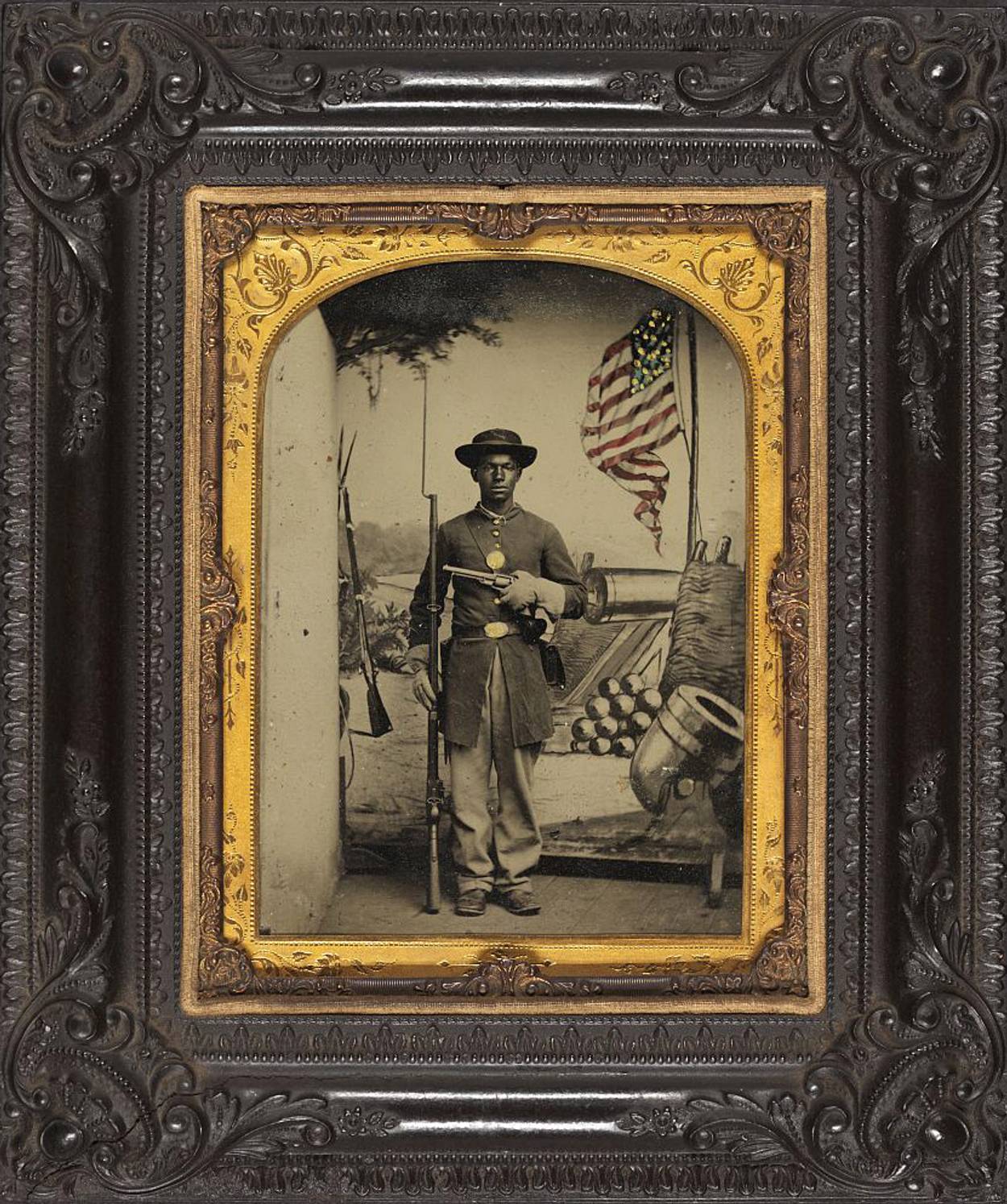

Naturally he understood what was the issue locally at hand in the United States at his own moment. He expresses it with magnificent tenderness in the greatest of his flag poems, “Ethiopia Saluting the Colors.” This is a rhyming poem with a scheme of three-line stanzas, the first line rhyming internally, and the second and third lines rhyming with each other—not the sort of thing he went in for, typically. It is conventionally melodic, or almost so. And the melody recounts a simple anecdote: The more-than-100-year-old African woman, “Ethiopia,” stands at the side of the road, recalling to the poet how she was captured like a beast in Africa and delivered to the cruel slaver. And meanwhile she watches William T. Sherman’s army march by, on its way to the sea and victory over the South. And she nods and curtsies and marvels. Nothing more is said, nor are the “colors” described. The poem’s reserve is its power. The cause of man and of democracy: This is the cause that is marching by, victorious, and is receiving the most humble of salutes, which is also the grandest, which is that of the very old and very bitter lady, who has forgotten nothing.

Ah, Whitman. Every time I open Leaves of Grass, the warble in his tone catches me by surprise—so strange and plaintive, so otherworldly, the vibrato so pure and dark. I look at the flag, and it is Whitman’s flag I see, and not the politicians’—the sprinkled bunting, vigorous, deathly, ideal, hopeful, tragic, and weirdly melodious.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.