Can Religion and Poetry Coexist?

For Zoketsu Norman Fischer—retired abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, experimental poet, and founder of an influential Jewish meditation group—the question is the answer

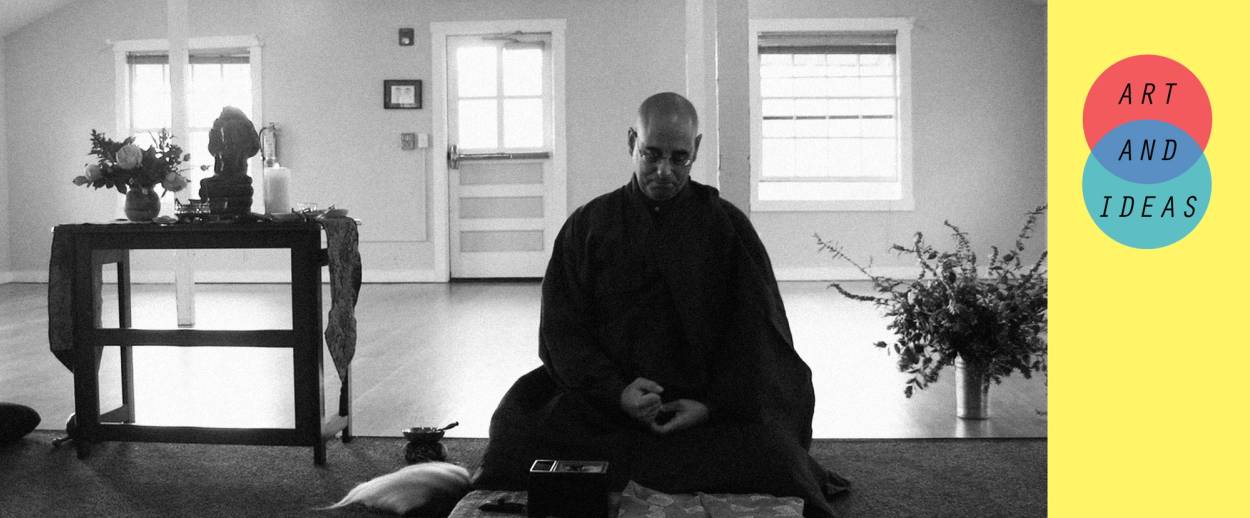

“As a poet, I certainly believe that every word means its opposite,” said Norman Fischer with calm deliberation, and with the sort of nonchalance one reserves for matters entirely self-evident. Garbed in his priestly Zen robes, he went on: “I am trying to wake up language to myself.” We were at the Spirit Rock Center Meditation Center in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. The meditation hall was filled with more than a hundred people on neatly arranged chairs, with many others on the floor on meditation pillows or yoga mats. The crowd was alert, listening deeply. The subject of the daylong retreat was Nothingness, as it is expressed in Jewish and Buddhist traditions. The session was co-taught by Fischer—a retired co-abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, founder of an influential Jewish meditation group, and an experimental poet—and the groundbreaking translator of the Zohar, Daniel Matt.

In his presentation, Matt—thoroughly prepared with handouts that featured stellar quotations from the ancient Jewish texts—was scholarly. Fischer, on the other hand, brought “nothing,” and was wholly prepared to improvise: riffing, responding, even bantering. In the small bi-coastal world where Judaism and Buddhism intersect, Fischer is widely read and respected, but not as a guru. In his bearing, he’s rather like a small-town rabbi, a scholar surrounded by a coterie of avant-poetry legends. He’s disarmingly secular and non-dogmatic in his thinking—just as he’s haimish about his family and friends.

“Every word means its opposite,” reverberated through my mind. That’s something I associate with the Talmud. There, you get a discussion of the word ohr, which normally means “light,” but in the context of the Passover celebration, may actually come to mean “evening.” Additionally, perhaps the words’ reversal is something one can think of in the context of dreams, and psychoanalysis—where the emphasis is on the symbolic, rather than actual. But how can one compose poetry, with an awareness that words are not pointing toward the meanings we expect, that lines that come to us do not actually mean what we intend them to mean?

The Nothingness that Fischer spoke of throughout the retreat is not nihilistic. It’s an intellectual and spiritual horizon, and it is an idea, which, for Fischer, is rooted in Soto Zen, mystical strands of Judaism, and the late 20th-century literary theory and philosophy that informs the artistic circles Fischer has been drawn to since the early 1980s.

***

Some days after the Nothingness workshop, I drove from Stanford, up the coast to visit Fischer at his home in Muir Beach. California’s iconic Highway 1, immortalized in endless films and novels, gave way to one-lane roads and sharp turns. The views were breathtaking over the ocean and mountains, with wildflowers bursting from winter rain. Fischer and his wife, Kathie, also a Zen teacher, warmly greeted me at the door. This time, I noticed, Fischer did not sport the robe or any ritualistic wear: His outfit was as nondescript as it gets. The home, though, was colorful and inviting, with artwork, books, comfortable couches, and windows facing the ocean. The home, Fischer explained to me, as we went for a stroll outside, was willed to him and his family by a friend and student; it is down the road from the Green Gulch Farm, where Fischer lived, taught, and brought up his twin sons. Before long, maestro invited me to an elaborate bean salad prepared by Kathie.

A small shack outside of the home is where Fischer receives his regular students, who come to talk to him about their spiritual practice. A slightly bigger building houses the study, where we conversed about his life’s work.

“I don’t find them particularly interesting or important,” Fischer said about the biographical facts of his life, “which is why I don’t write about them.” He was born in a small Pennsylvania town to a Conservative Jewish family. The first in his family to attend college, Fischer was also the only student in his graduating class to have gone to a college that was not local (Colgate University). An early important influence on Fischer was the local rabbi, who happened to be Jackie Mason’s brother, and was a deep reader and engaging conversationalist. Early on, Fischer received his MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop. He went there to write prose but, turned off by commercially minded colleagues, quickly found kinship with the program’s poets. Consequently, he came to the Bay Area, where he started practicing Zen meditation and formed important friendships within the great literary scene that unfolded on the West Coast in the 1980s—an experimental group that came to be known as Language Poets, whose aesthetic still deeply informs Fischer’s writing.

“There is a sense of reality in the language itself … the language itself is the reality that creates a world. The language I’m not in control of. It is through fully situating myself within language that this world, the true world, a real human world—and beyond human—occurs. Language itself is the mystical experience, if you will.”

This isn’t esoteric, nor did Fischer try to be. He spoke plainly, avoiding jargon, instead opting for vernacular, casual turns of phrase. These ideas, Fischer told me, resonated with his original understanding of the Language Poets’ aesthetics, and the contemporaneous literary theory. It also cohered with his findings within his fledgling Zen practice: “As I got further into my practice, conventional notions of character and self became a problem, and also language became a problem because I was more attuned to the immediacy of language rather than the artifice of it, using it to set a scene or paint a character.”

Nor is mystical experience of language something unattainable, reserved for the select few. The inspiration, as he described it, is rooted in “a state of mind that comes partly from cultivation of my spiritual practice over time, and partly from many hours contemplating texts of all sorts. … Any kind of reading that is trying to penetrate language and is not just reading for information or content—that is itself a contemplative practice.”

For Fischer, this stance isn’t a strictly inner, personal experience. The questions he’s positing expand toward the political realm as well. He reflected, “This is the conundrum, the problem: How do you have serious spirituality that’s fully open to the other? That’s what we need. And that’s the job of language. Every intense spiritual tradition is a language, and once you get inside of it, you end up being narrow-minded. But if you could be inside that language system and understand it as a language system, and be able to translate, and not be narrow?”

That, said Fischer, is his life’s work and, he added smiling, a losing battle.

***

In the introduction to I Was Blown Back, Fischer writes: “I am often asked, ‘How is it possible that you are a Buddhist priest who also practices and teaches Judaism?’

“Why is this a question? To me, there’s no problem here, and there could only be if one saw truth as propositional and therefore explainable, with one explanation canceling or obviating another. But truth isn’t anything or, if it is anything, it is a shifting shape, a feeling, not an explanation.”

Fischer may not put much stock into “explanation,” but his approach to religion is striking for the way it resembles contemporary thinking around questions of identity, and in particular, gender identity. One wonders, can we think of religious beliefs in the same way we’ve come to think of gender: as fluid, inclusive, expansive, changing?

It is clear that encounters of Judaism and Buddhism are important for Fischer, and he spoke at length about his friendship with Rabbi Alan Lew, who was at one point, a fellow student at the Iowa Writers Workshop and later a partner in co-founding a Jewish meditation center, Makor-Or. Jewish meditation, rooted in Zen practices, the poet told me, was once viewed with suspicion but has been embraced in recent decades.

“Judaism can’t resist anymore things like intermarriage and mixing with other traditions,” he said, “and now it is embracing it all as a way of admitting a fact that can’t be resisted, and at the same time, using it to strengthen itself.”

As we discussed Jewish hermeneutics and mysticism, fundamentalism and assimilation, I felt uneasy asking the question that had been nagging me, but finally went for it.

What about all the statues and images I’d been noticing around the house?

“I never had a strong problem with it. I never felt that I was bowing to the image, that this image is a deity. Buddhist images at their best could be wonderful pieces of art, especially as, in fact, Buddhism is not deistic. All these are representations of qualities within one’s own heart. You’re bowing to the wisdom you’re trying to cultivate. When the Torah says ‘Don’t bow to the image,’ I think it means don’t practice idolatry—that is, don’t think that any limited dualistic notion is what is meant by YHVH. You can be idolatrous with normative Judaism—worshipping Judaism in an idolatrous way.”

***

An untitled poem opens Fischer’s collection I Was Blown Back, published a bit over a decade ago:

A thousand people contained within a lit square

Three trees silhouetted straight up branching eerily out

Ordinary clouds stream against the fluted airways –

How their smoky fingers make music against the dark

Quietly what’s good

Descends like dust

Or dusk onto the milky landscapes

The people stand still

And all around them

The bluster of their thinking

Pulls down lightning from above

And the platforms rattle

The owls in the trees scatter their nocturnal alarms –

How decisive the universal defeat

The setting here is mythic, though it may as well find a home in a science-fiction novel. The visual landscape is fluidly transforming as the poem proceeds: nearly every image is in motion.

The urban “lit square” clashes against all of the natural symbols—trees, clouds, lightning, and owls. What sort of a place is it? Who are these people, and what is the occasion of their gathering? There appears to be a significant, perhaps singular, communal experience that is happening in the poem. Something Sinai-like—except that instead of a revelation, the group is surrounded by the “bluster of their thinking,” which, nevertheless, miraculously engenders the lightning.

And what to make of the third stanza, where the “what’s good”—a euphemism for the divine?—descends “like dust”? What a simile: That which we consider omnipresent is, here, compared to the utmost fleeting, simple, pestering image that bespeaks of mortality. If this is a revelation, how can it also be, as the last line attests, “a defeat”—and whose defeat is it, anyway?

Perhaps the poem deals with spiritual experiences, and our inability to interpret them, or anyway, get beyond the “bluster.” Or, to the contrary, one can interpret the defeat as something positive—a rapture of sorts, universe-wide victory over the vanquished ego. Defeat is victory—for indeed, every word means its opposite.

In the introduction to I Was Blown Back, Fischer describes writing as a mystical experience: “Words were coming from elsewhere, or at least nowhere, and do not describe anything I have seen or experienced.” There’s no doubt that much of the above poem does not allude to reality that can be grasped with sensory perceptions. It’s an abstraction, an interpretation perhaps. Is it possible, then, that the experience the poet is describing is not a peak moment—but simply an ongoing the state of humanity as such?

In his essay “On Questioning”—part of the recently published stellar collection Experience: Thinking, Writing, Language, and Religion—Fischer speaks of the essence of Zen, in a way which is every bit as applicable to great poetry, and certainly to Judaism, all in a breathtaking poetic and philosophical volley:

What is the essence of this radical freedom that Zen teaching seems to be proposing as the core of the religious quest?

It’s questioning. The active, powerful, fundamental, relentless, deep, and uniquely human act of questioning. … Questioning that produces a doubt so deep and so developed it eventually becomes indistinguishable from faith. Questioning that starts with language and concept but quickly burns language and concept to the ground and enters silence. Questioning that brings humanness to the edge, and pushes it off. So that the feeling of being, of existence itself, as manifesting in a particular time and place and person, becomes foregrounded.

If the question itself becomes the answer, or even the faith, as it appears above—is it not true that every word indeed, means its opposite?

***

Read Jake Marmer’s poetry criticism for Tablet magazine here.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).