The artist William Pachner, in his 103rd year, was lying in his sun room in upstate New York, his tiny, frail frame angled toward his backyard meadow and the dark green slopes of Overlook Mountain.

He opened his eyes, one small and light brown, the other large and light blue.

“Look this way, the meadow,” Pachner said. “The sun—the beautiful radiance. Paradise.”

When he first saw this mountain range, in 1939, he was on a train traveling west through the Hudson Valley. He was carrying a portfolio of his illustrations, and had just arrived in America. With his one good eye, he looked out the window at the spectacular landscape, which resembled his European homeland, and said to himself: “This is where I’m going to live. This is where I want to spend the rest of my life.”

That was before he became Esquire’s art director and a renowned anti-fascist illustrator during World War II whose depiction of Roosevelt graced the cover of Collier’s magazine. It was before he learned that his family had been killed in the Holocaust, which led him to quit commercial work and become a painter whose work became internationally recognized. And it was before he lost the vision in his good eye, yet continued painting, in black and white.

Those who’ve known Pachner have described him as a highly unusual person—a sort of philosopher whose poetic use of language, commanding presence, and expansive knowledge of history and literature made interactions with him enlightening, entertaining, and intense. They saw him as a source of great wisdom and an astute observer of human nature with an intolerance for superficiality, sugarcoating, and empty pleasantries.

In the daytime, Pachner recently said, he could only distinguish between dark shadows and bright light, white and dark, while in the evenings he couldn’t sleep, and “the whole motion picture of my life passes unwittingly, unwantingly—I don’t desire it—but with great vividness and authenticity, and like a tremendous newsreel.”

Often, he said, he saw the expressions in the eyes of people he loved and lost, during times “of great joy, of being together, and a time of deep sorrow—the full circle of life.” And about his paintings—which, like his life, have encompassed the extremes of the human experience—he thinks about which ones were good, which ones weren’t, and the works of art that will be remembered long after he’s gone.

I discovered Pachner while researching living centenarians who had long ago made a cultural impact but had perhaps become forgotten. I took a bus from 42nd Street in Manhattan to Woodstock on a recent Friday afternoon. “Nana,” who helps care for him, picked me up and drove me to the house, which is up a winding road from Woodstock’s village square. Bill, as friends know him, doesn’t receive many visitors anymore, she said.

The white house, built in 1934, sits on a quiet, four-acre property with tall trees in front and a little stream in back. I was led through the house’s bright main room, which is as immaculate as an art gallery, with light wood floors, colorful furniture and walls decorated with Pachner’s paintings, and into the sun room, where Pachner himself was stretched out across a recliner. He looked dressed for the occasion. He wore black-framed glasses, a blue sweater and khaki pants, and brown loafers. I heard the chirping of crickets and crows, and the faint sound of water running through the stream.

When Nana announced my arrival, Pachner stirred awake. He and I began by graciously quibbling over the seating arrangements: I insisting that he park himself where he was most comfortable, and he strenuously objecting and that I first choose on the grounds that, as he put it in his Czech accent, “You are my guest!”

Eventually, he sat near the edge of the recliner, on the end closest to the floor-to-ceiling window that looked out on the meadow; I sat beside him, in a chair. He was so tiny on the furniture that even while both seated, I towered over him.

“How are you feeling today?” I said.

He angled his head almost straight upward, stared into my eyes, and clutched my arm firmly.

“I wish you wouldn’t ask me the usual thing,” he said kindly. “‘How are you?’ ‘Fine.’ ‘And how are you?’ ‘Fine.’ You know, we put on our best—”

“Of course,” he said, “I am sitting down, but I could actually walk with you throughout here, but that sounds like bragging. I am not bragging. I am past that point.”

“You can brag to me if you want,” I said.

“You are very kind,” he said. “What may I call you?”

“Plain Louie? I shouldn’t call you with any official—”

“No! I’m very informal. Louie.”

“Wonderful,” he said. “Wonderful.”

Over the next few hours, Pachner peppered his speech with sayings from writers like Bellow, Faulkner, Mann, and Vonnegut. Often, rather than answering questions directly, he began with quotations from literature, expecting me to interpret their meaning.

He spoke passionately and with precision; he continually self-edited his sentences, appending verbs and adjectives until settling on the word that best reflected his feelings. (“He builds a sentence as he painted a painting,” Pachner’s friend Jim Murphy told me later.)

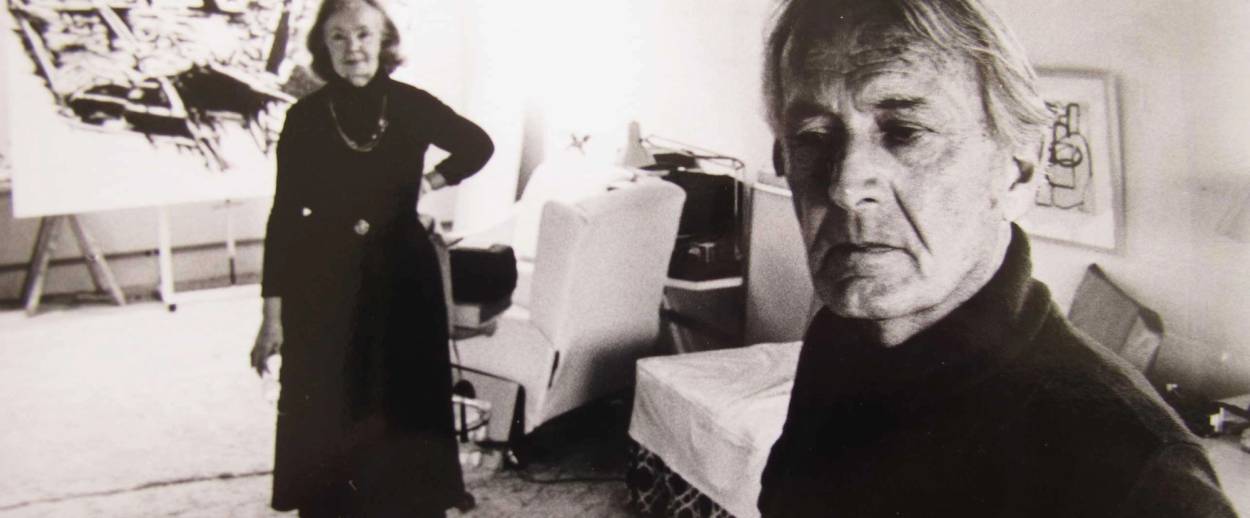

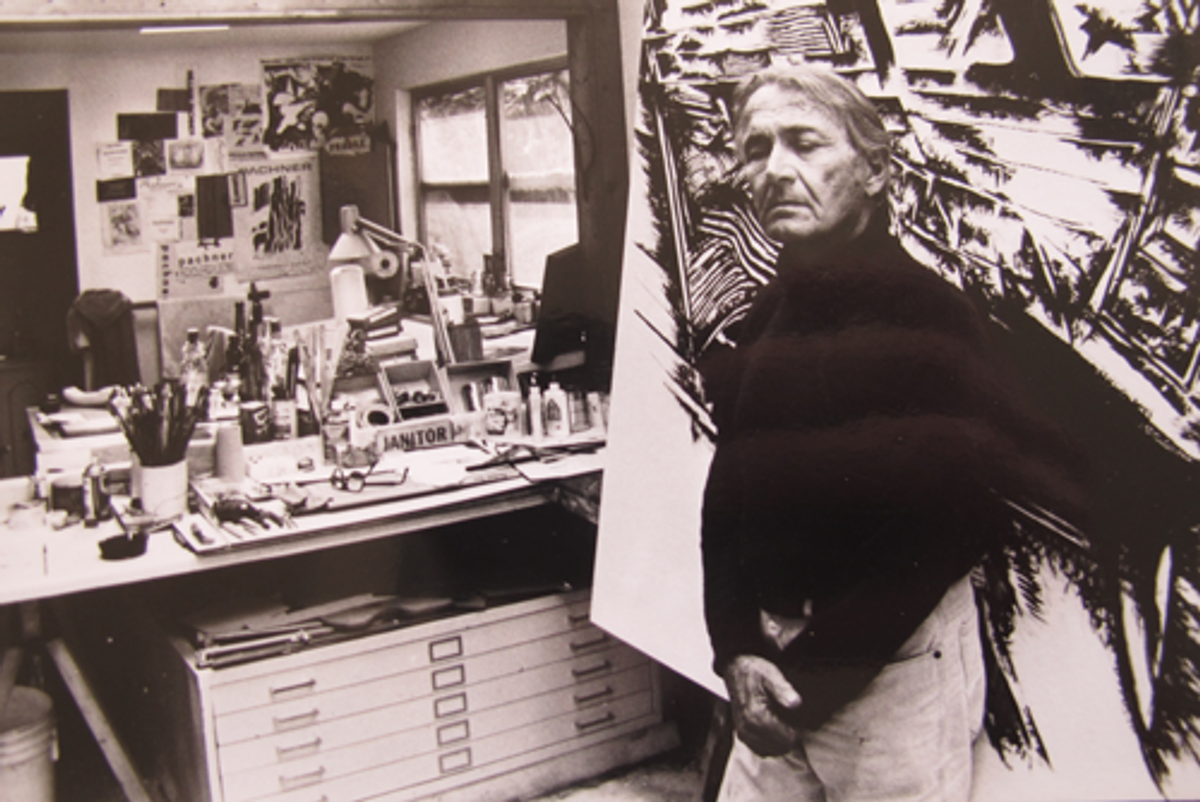

Pachner in September in the sun room of his Woodstock home, where he has lived since 1945. (Photo: Louie Lazar)

Upon stating something that he realized possessed absolute truth, he said, “Ahh,” or “Mmm,” and stopped talking.

All of that, combined with his wild, wind-swept-looking silver hair, made being in his presence feel like I’d been conversing with a knowing but provocative thinker from an earlier era.

“I was born to be an artist,” he began. “It came naturally, in a way the bird sings, the cow moos, or the dog barks.”

I’d asked him to speak of his youth, in Brtnice, a town about 75 miles southeast of Prague.

“I was born in the very heart of Europe, in the highlands between the ancient kingdom of Bohemia, and the province of Moravia,” he continued. “It was in the Hapsburg Empire, during the reign of Emperor Francis Joseph. Just imagine!” He inflected the last word in a whimsical, high-pitched manner, looked at me momentarily with a twinkle in his eye, and went on. “My dear father told his friends to get paper because my son would otherwise draw on the walls.”

Pachner spent summers with his grandparents in Bohemia. His grandfather, Leopold, encouraged his parents that Pachner “be left alone to become what he aspires to be. Don’t fiddle with him. Let him go within for his orientation, not look outside for it.”

Pachner loved to draw trains. “It was the 1920s, the war was over, and the technology was the trains,” he told me. On a visit to Bohemia, Leopold brought William to a local rail yard, and persuaded the engineer to give him a ride.

As William wandered the train, with its hanging kerosene lamps, he looked around in wonder. “Here was the technology, there were the windows, there was a fireman who fed the fire with coal—it’s all connected, things are not separated, they are all one,” he remembered.

One day, at age 5, Pachner was sharpening a pencil with a kitchen knife, and he stabbed himself in the left eye. His vision in it was lost.

But he kept drawing. Anna, his mother, and his father Josef, who smoked a pipe, supported his pursuit. Like Pachner’s grandfather, they too “understood the fundamental principle that human fulfillment has to do with doing the work which is inseparable from your nature,” Pachner said. “They never said, ‘You will not be an artist because you will not make any money.’ ”

Pachner studied fashion illustration at a design school in Vienna, then worked as an illustrator for a publishing house in Prague. In 1935, he became a staff artist for Ozv ny, a Czechoslovak illustrated weekly.

He subscribed to Western journals like Esquire, for whom he wished to become a contributor. He had developed an “unquenchable ambition,” he said, to strive further artistically.

“I was finished with Europe,” he said. “It was old and dead, exhausted in every way. America was my aspiration.”

Pachner obtained a temporary visa to visit the United States. His family—including his parents and aunts and uncles—joined him at the train station to say goodbye.

“But no one knew it would be forever,” Pachner said. No one believed there would be war; rather, his journey was seen by everyone as merely the first of many trips by a restless young artist. “I remember them, the faces,” he said.

On Mar. 9, 1939, his ocean liner, the Queen Mary, arrived in New York. Less than a week later, unknown to Pachner at the time, German troops marched into Czechoslovakia. Hitler, from a castle in Prague, declared Bohemia and Moravia part of Nazi Germany.

Pachner rode the 20th Century Limited, a famous passenger train on the New York Central Railroad, across the Hudson Valley. His destination: Esquire’s office in Chicago. Once downstairs, he took an elevator to the 13th floor. Behind a reception desk sat a young woman, the editor’s secretary. She was from Iowa, and beautiful.

“Without saying a word I gave her a kiss on the mouth,” Pachner said, “and she was not taken aback. She kissed me back. I didn’t say anything. A date was made sometime later.”

By the following year, Pachner was the magazine’s art director, and he and the woman, Lorraine, were married. They had two children: Ann and Ned.

Pachner had learned by radio one Sunday of the German invasion of his homeland. For a while, he stayed in touch with his family in Europe. Thousands of letters were exchanged on flimsy paper.

“Being 24 years old, I told them how great I was—how I’d already gotten a job,” Pachner said.

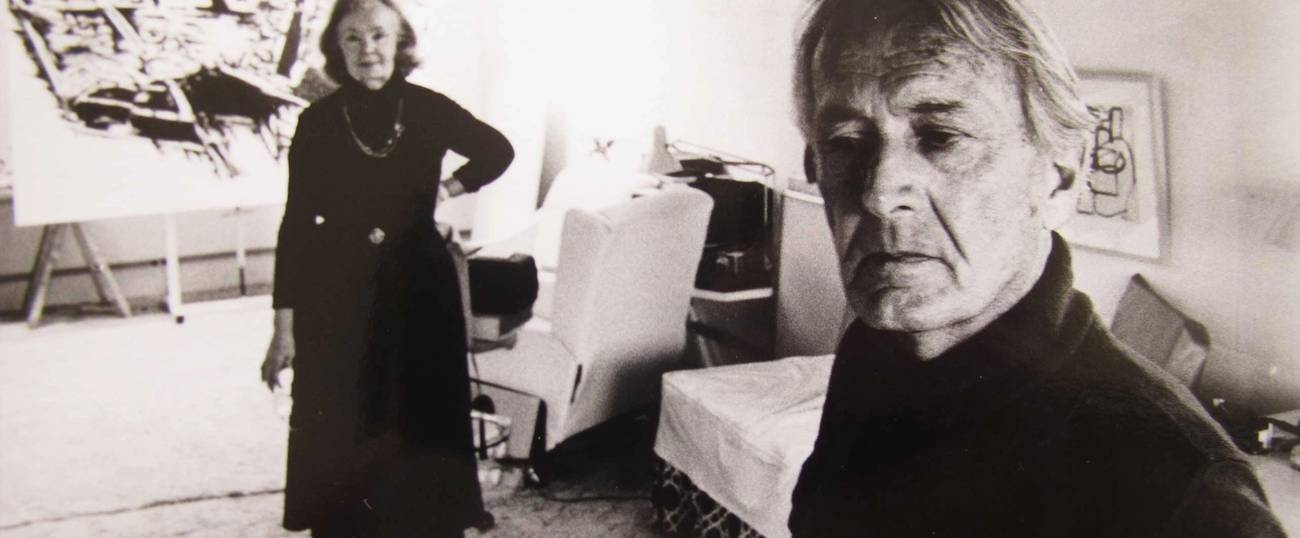

Pachner’s renowned illustration of President Roosevelt, which appeared on the cover of Collier’s in early 1945.

Of his parents, his mother was “the expressive one,” Pachner said; she did the writing, and always signed off with the words, “A Thousand Kisses.” His father added the appendix, “With Love.”

Pachner also received letters from his younger brother, an aspiring writer who was tall and handsome—the three Pachner men looked alike—and who, like Pachner, had begun smoking a pipe to emulate their father.

Like many emigrants, Pachner wouldn’t learn of his family’s fate until after the war.

By 1943, Pachner had become one of America’s most “outstanding illustrators and fashion artists,” the Atlanta Journal Constitution said.

Pachner tried to enlist in the Armed Forces, but was rejected because of his eye. Determined to contribute to the war, he resigned from Esquire. He moved to Manhattan and created anti-fascist illustrations for major magazines.

“The world had changed; I wanted to broaden my field of expression,” he said.

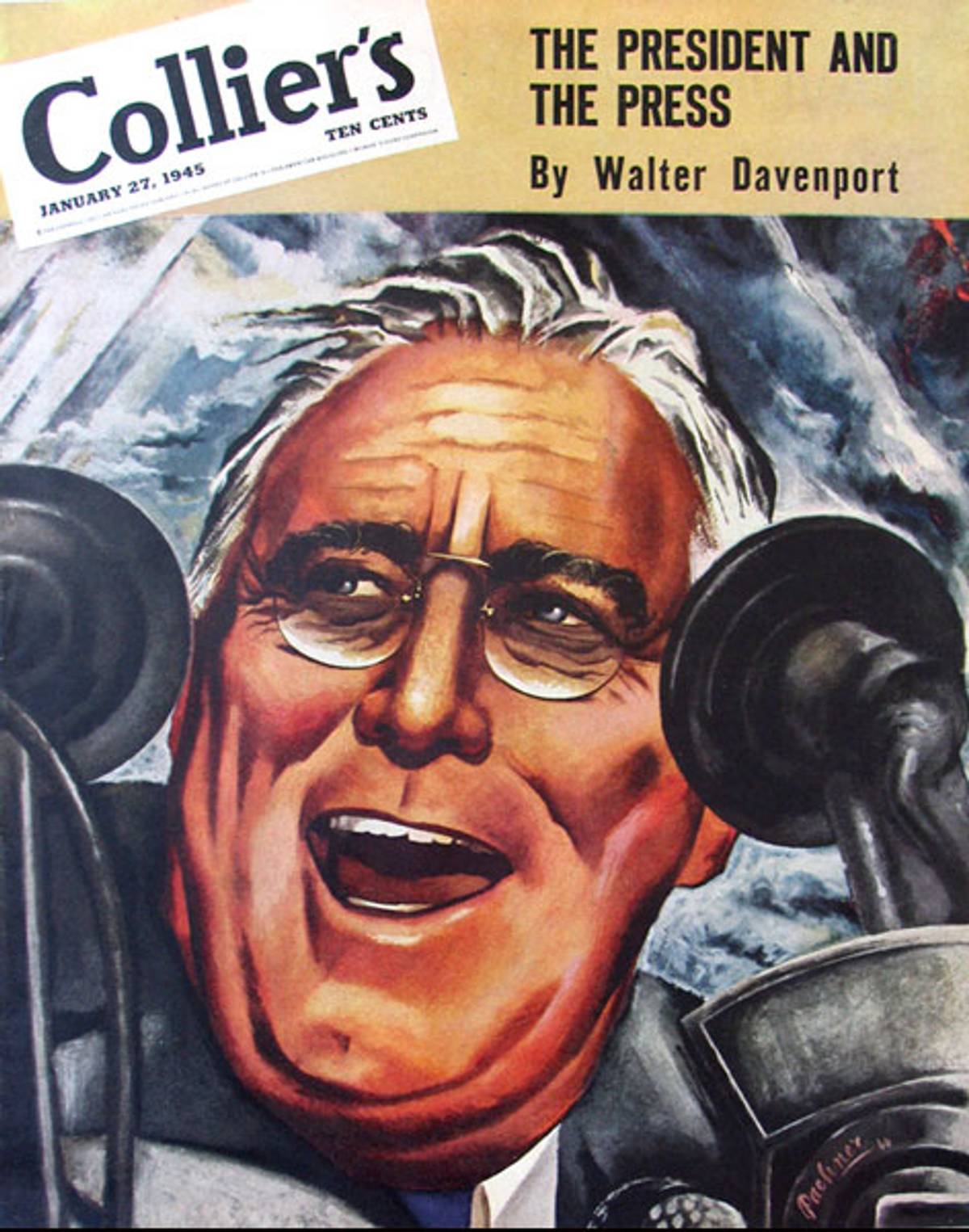

His work included “German Train,” a 1944 illustration for Collier’s depicting a nighttime scene of Jews massed inside and outside of boxcars. The drawing accompanied an article by Jan Karski titled “Polish Death Camp,” based on the writer’s firsthand account of a deportation.

“Now that millions know, they will not forget,” the writer Manuel Komroff wrote in 1944 of Pachner’s illustration. “And they cannot possibly forgive.”

“Pachner’s illustration of a deportation,” according to a retrospective catalogue published by the Florida Holocaust Museum, “was as accurate as any photograph taken of this crime by the perpetrators themselves.”

Another illustration, which Pachner created to promote a clothing drive for anti-fascist exiles of the Spanish Civil War, depicted refugees, the tallest one resolutely carrying a young girl.

But his most famous work was the illustration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Pachner’s hero, that appeared on Collier’s cover on January 27, 1945, and showed a joyous and decisive president giving a speech. Roosevelt died three months later.

Later in 1945, Pachner received a telegram from a friend at the soon-to-be-established United Nations, with news from Prague about his family.

“No further hope,” it read.

Back in his Woodstock sunroom, Pachner fell silent. His son, Ned, told me by phone from his home in California that his father never spoke openly about what had happened to his family.

But, Ned said, “those themes, those emotions, that history, is all right there in his paintings.”

One Sunday near the end of the war, Pachner received a call from Komroff, who knew of Pachner’s wish to live by Overlook Mountain. Komroff had seen a New York Times notice announcing the sale of a house in Woodstock belonging to the founding director of the Whitney Museum.

“It’s the best house in Woodstock,” Komroff told him.

Pachner took a bus from 42nd Street to downtown Woodstock, where a real estate man picked him up and drove him up the winding street to the residence, on Ohayo Mountain Road.

‘This is it,” Pachner said, upon seeing it. “It is home.”

He bought the house with money he’d saved from his commercial illustration work, which he quit to focus on painting.

“I had to conform to my inner experience,” he said. “The work I’d been doing was untenably, unbearably, on the surface.”

Every day, Pachner awoke before anyone else in the family and worked in his studio, whose glass windows offered a clear mountain view, starting at 5 a.m.

“The paintings were an initial searching—very difficult,” Pachner said.

One painting, from 1945, showed Jews in striped uniforms being driven away in the back of a truck. Seated tall amid the hunched victims, and staring at the viewer, was an oversized, compassionate-looking silhouette dressed in black.

A William Pachner illustration in a 1944 issue of Collier’s.

That theme, of a sort of ghostly but benevolent force providing comfort to the oppressed in spite of impending and inevitable doom, was present in other early works of Pachner’s, including some huge paintings with biblical motifs. In “Moses,” a colossal, long-bearded figure protected a faceless, helpless creature amid a treacherous sea and sky. In “Israel,” a giant, partially-invisible male consoled what appeared to be an old woman with hands covering her face.

Pachner also produced satirical works attacking the moral vacancy of powerful people. In “His Spiritual Highness in a State of Moral Dilemma,” a commentary on the Vatican’s unwillingness to denounce Nazism, a king-like person, although not entirely human, sat complacently on a throne as a horrible fire raged outside an open window behind him.

“How can the creative artist remain aloof today?” Pachner said in a 1948 interview with the New York Herald Tribune. “What period could more imperiously demand the artist’s dedication to the cause of mankind?”

Often, Pachner’s paintings simultaneously contained beauty—both in color and in his subjects’ compassion—alongside images of death. His painting, “Night Scene,” showed a partial skeleton in a setting brilliantly illuminated in gold. “Terminal Number I” was defined by colors in which a multitude of human shapes—perhaps adults as well as children—appeared lively and vibrant, with some blotted out in white.

As Ned puts it: “If you go into the work—the yin and the yang—you can see the ecstasy in living as well as the horror of extermination. It’s all in the same painting.”

Pachner’s work was exhibited in Manhattan and around the country. Critics for the Times and Herald Tribune praised his technical skill, comparing his large canvases to early Flemish and German religious paintings.

He won awards, including grants from the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, which commended Pachner for “masterful use of powerful design to express a deep emotional experience.”

For that award, his photograph was published in the Times alongside seven other artists’; only Pachner had a pipe dangling from the side of his mouth.

The Austin-American newspaper called him “one of the most highly respected artists in contemporary circles,” and the Whitney Museum purchased a large painting of his for its permanent collection.

Pachner became associated with the Abstract Expressionist movement and The New York School. But he denied to me that he was part of a movement.

“Or any damn school,” he said. “It’s ridiculous.”

Pachner was adamant that it had been the beauty of his home’s natural setting that had attracted him to Woodstock, “and not because somebody said, ‘Woodstock is an artist’s colony.’ That would have been enough of a reason for me to stay out of there!”

Nonetheless, Pachner became friends with artists and literary people who made their homes in Woodstock, like the painters Philip Guston and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and the poet and novelist Michael Perkins.

At their house, the Pachners hosted parties at which Lorraine cooked turkeys or hams and mixed cocktails. They also attended parties, like the poolside 1890s-themed costume affair in the summer of 1950 at which, one local newspaper reported, judges awarded “Mr. and Mrs. Pachner” the prize of “Best-Looking Couple.”

Pachner found and rehabilitated a beat-up, teal, 1931 Model A Ford, which he drove while smoking his pipe. The car reminded him of his childhood and father, who had bought an automobile in Brtnice.

Pachner, dark-haired and tan, spent his mornings painting in solitude and his afternoons gardening. Classical music played constantly from a radio in the house.

During summers, he and Lorraine drove to Tanglewood in Massachusetts to hear the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Pachner, who called Mozart “my great love,” knew all of the music by heart, and hummed or sang along.

And Pachner read tirelessly, including all of the classics. “He was like a Renaissance Man,” his friend, Joe Lupo, said.

Perkins, the poet, was first drawn to Pachner by his mastery of language. “Highbrow or lowbrow,” Perkins once wrote of Pachner, “he rings all the linguistic keys, dazzling his innocent interlocutors with accents, jokes, and references that sail over the heads of most. (He has no patience for fools, but far from being snobbish, he treasures workmen and seeks the company of honest, ordinary folk).”

Friends of Pachner’s told me that he could have been a great actor for his ability to command a room and tell stories without being ostentatious, a great philosopher for his ability to apply concepts from literature to ordinary situations; a great psychoanalyst for his skill in dissecting people without offending them (“He can read people, just peel layers off,” Lupo, a former child psychiatrist, told me. “He knew more about what makes people tick than many of my colleagues.”)

In the 1950s, Pachner began teaching and established a winter home in the Tampa Bay area, where a popular art scene was emerging.

Marge Dimmitt, 88, is a professional painter who in the 1960s was a student in Pachner’s Clearwater workshop. She called his classes “unforgettable—one of the great experiences of my life.”

Dimmitt said that she and her fellow students—ranging from their early 20s to late 70s—looked forward every Friday morning to Pachner’s class, which met in a small studio at the end of a curved road.

Sometimes, Dimmitt said, Pachner would have the students paint. But often, an entire class period consisted of a student asking a question, and then Pachner, sitting on a stool, speaking non-stop.

She remembers sitting captivated with her classmates as they took in Pachner’s “philosophic thinking, and his quiet wisdom.”

“He expressed himself beautifully, succinctly,” she added. “And he was always right on.”

Many of Pachner’s students became professional artists. Others, who were amateurs, also felt his impact, like Victor Bergstrom, a white-haired Manhattan pathologist suffering from severe anxiety and who wound up in Florida as Pachner’s student.

Bergstrom described Pachner, according to a 1960 column in the St. Petersburg Times, as “the most inspirational man I’ve ever met,” and learned that “the sunset years can be a canvas of glowing brilliance instead of a sad study of creeping twilight.”

Pachner steered conversations toward certain themes. “He felt that too much of the human race was being lulled into staying at a surface level and being materialistic, into taking the easy way out or the narcissistic, self-centered way out, and they don’t look deep enough into themselves,” Lupo said. “Be honest with yourself, don’t fool yourself—he really went deep into that. But he did it in an intellectual, supportive, warm way.”

‘Landscape of the River Sola,’ a 1966 painting depicting The Sola, which flows beside Auschwitz. Pachner considered it his finest work. (Courtesy the Pachner family)

After the 1940s, Pachner’s own work became more abstract. “Some ghosts of figures and landscapes lurk beneath his elaborate manner,” wrote Stuart Preston, the Times’ art critic, in 1961, “but what chiefly impresses is the care with which he builds up his shapes as they wander between light and dark.”

At a glance, many paintings were simply mixes of attractive colors. But in fact, they were landscapes—fields, forests, and rivers—sometimes scarred with human-made objects like roads, watchtowers, or train tracks.

“And it’s never just a landscape—it’s his memories,” said Erin Blankenship, the curator of exhibitions and collections at the Florida Holocaust Museum.

Every year, the Pachners’ grown children returned to Woodstock or Florida and spent two weeks with their parents. Like when they were young, their time together revolved not around the celebration of places or events—like vacations or birthday parties—but in life’s subtle joys: of talking, of sharing a meal, of going on a walk.

Then, as always, Ann Pachner, who’s also an artist, told me: “My father treated us as precious because, I think, of losing his own family.”

All the while, Pachner flourished professionally. By the 1970s, according to art critics, Pachner had become “an established star” and “the best artist in Florida.”

And, as always, when he worked, next to his easel rested a photograph of his parents, sitting together on a bench.

In the 1970s, Pachner developed a cataract in his good eye. He still painted—he and his family even moved into a new house in Tampa and he built a new studio there—but shapes and colors became increasingly clouded over as the condition worsened.

In 1981, he underwent an eye operation. Immediately after the surgery, Pachner was ecstatic.

“I’m seeing colors in an intensity I’ve never seen in my life,” Lupo recalled Pachner telling him. But within a few days, everything changed.

Something had gone wrong and the retina had detached. As his sight deteriorated, he accelerated his pace of work, racing against time.

By 1982, Pachner could no longer differentiate colors. Further surgeries failed to help.

“It was a profound blow,” Ned said. “Psychologically it was a death of some sort.”

Friends say Pachner appeared more melancholy. On Saturdays during the winter, Pachner and Lupo walked along the bay.

“He’d get down and depressed,” Lupo said, “but he dealt with it well, or hid it from others.”

From his outgoing nature, Perkins said: “He seemed to retreat. He shed friends.”

“I was in the depths—the blackest hole I have ever been in,” Pachner once said of that period.

But as Pachner’s vision faded, his other senses began heightening. “He could feel the breeze, hear the birds, really commune with nature so well,” Lupo said. “I think his inner-eye came out.”

Exactly what Pachner “saw” is unclear, but in a 1984 interview, he described processing—from the corner of the eye he’d lost in childhood—some light, through which he could detect movement.

“It is through that eye that I try desperately to grab the world,” he said then. “All my life I have rejected that eye, only to find that it is my treasure.”

A few years after losing his good eye, he tore apart a watercolor painting. “The old work is finished forever,” he told himself. He rearranged its fragments on new paper. He titled it “Number One.”

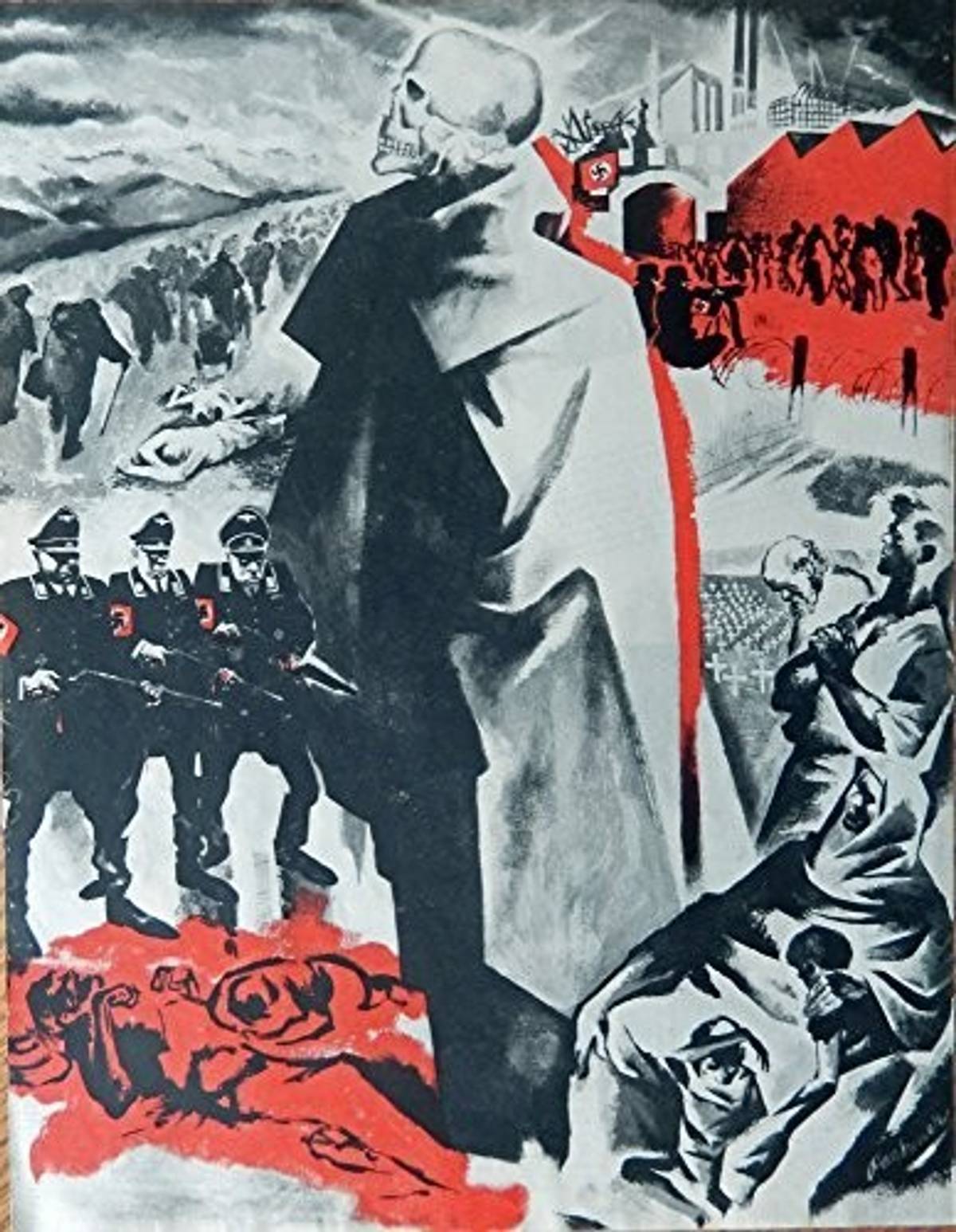

He began creating large paintings and collages in black and white, whose contrast he could distinguish.

One painting, “Steam Engine,” showed a train’s wheels violently blasting the machine forward. In “Train and Tunnel,” a locomotive with a small barred window sped into a dark tunnel. Another painting, “Howling Forest,” was of a mouth screaming frantically out of the center of a tree, part of a face swallowed up in its branches. There were also self-portraits in which one or both eyes were blotted out in black.

Lacking the vision to amend his paintings—or to mesmerize with color—Pachner had to conceptualize images in advance and then work rapidly, by feel.

“It was like a stream of consciousness,” Ned told me. “It was a spontaneous expression—there was no editorializing it. It was extremely cathartic for him.”

Galleries exhibited his new work, which Pachner at the time called the best art he’d ever created. “I never could have done it with eyes,” he said then.

A reporter wrote in 1987 that Pachner “moved around with ease” in his Tampa studio, which was dominated by white: the walls, the couch, and rug, the paper that covered an easel illuminated by bright light. He worked from a jar of black paint.

“His haunting black-and-white images exude more power than ever,” the St. Petersburg Times said in 1988.

But the new work remained “little known,” the paper said. The reality was that its stark, non-decorative nature made it difficult to sell.

“An auction of paintings by internationally renowned artist and Tampa resident William Pachner turned up few buyers willing to pay the price,” a 1990 article began.

“I am not painting for anybody’s hotel rooms,” Pachner explained in 1992. “I am trying to deal with the full experience of life in the world.”

Or, as he once commented, his body of work represents “not a wedge of pie; it’s the full apple pie of life. Or cheesecake.”

Lorraine was an intelligent woman, as Dimmitt, who became friends with the Pachners, told me, with “a quiet sweetness about her.”

“She was strong and smart—she had to be, to keep up with her husband,” Perkins said.

A picture hanging in Pachner’s dining area shows that same room, in the winter of 1950, with his family seated around a table. The mountain behind them, the children are looking at the camera; Pachner is smiling lovingly at Lorraine.

After losing his vision in both eyes, Pachner began painting in black and white, whose contrast he could distinguish. (Photo courtesy the Pachner family)

In February 1994, Lorraine was diagnosed with leukemia. The following February, she died at home, in Woodstock.

When I mentioned Lorraine to him, Pachner became distraught and changed the subject. After her death, I was later told, Pachner wouldn’t speak about her. Their bond was “deep—beyond words,” Ann told me.

Shortly after Lorraine died, Pachner suffered fainting spells. At the hospital, he lost consciousness and his heart stopped. Family members thought he was gone. They hugged him and said goodbye. Doctors performed open heart surgery.

But he recovered and soon, he was back working in his studio, tending to his garden, and humming along to Mozart.

On many afternoons, Perkins and Pachner sat on the lawn talking. They spoke of reading, Perkins wrote, and agreed that “the human race is hopeless, but we must celebrate our humanity against the always-gathering forces of darkness, and an artist must do his job of reminding those who can still feel of the extraordinary preciousness of each passing moment.”

Between 1981 and 1999, the year Pachner’s vision became too impaired to continue painting, he created over 400 black-and-white artworks.

Even after that, Pachner’s old work was shown in Florida. In a 2004 exhibition, Modern Art in Florida: 1948-70, at the Tampa Museum of Art, it was featured along with that of Picasso.

And in 2005, the Florida Holocaust Museum held a retrospective exhibition of Pachner’s work, at which Pachner—according to a Florida newspaper—“held court Saturday night at the opening, charming dozens of admirers at a dessert reception held in his honor.”

Still, it had been many decades since Pachner’s art was exhibited in New York City, or mentioned in major national newspapers. “So nobody knows my work, really, in the art world,” Pachner recently said.

In 2007, Pachner was diagnosed with colon cancer and had surgery.

He continued landscaping in Woodstock—cutting grass, weeding on his hands and knees, caring for the flowers. (The grounds were “like a piece of art to him,” Nana told me.) But recently, his mobility worsened, and he had to stop.

His bedroom was moved from the home’s upstairs to the first floor. He began using a cane. Over time, his hearing had also deteriorated, and he required aids. To hear people, Pachner had to sit right alongside them. Visually and audibly, he couldn’t always tell if someone had entered a room.

A favorite hobby, maintaining and driving his Model A Ford, was no longer possible; the car simply sat idle in his garage.

All the while, his mind remained strong, although that was a source of frustration.

“He can describe a window he saw 70 or 80 years ago in phenomenal detail,” Ned told me. But that photographic memory, he added, “is both a blessing and a curse, like everything else in life.”

Last year, Pachner was determined to make changes to an old painting. He walked gingerly across the yard to his old studio. Dried-up paint brushes rested on the workspace beneath the window, whose mountain view had become obstructed by a neighbor’s trees. A black-and-white painting rested on an easel in front of an empty stool.

Fresh black paint was brought in, and once again, Pachner held a brush. He tried to work. But it was “fantasy,” Ned said. “He wasn’t physically, optically capable of doing it.”

Realizing he couldn’t do it, and not wanting to ruin the painting, Pachner stopped.

“I am a fraction of what I used to be,” Pachner told me.

During a break in our discussion, I walked around Pachner’s house. On the wall next to his bed hung a large black-and-white painting of a locomotive. On the opposite end of the room, next to a window, were framed pictures of William Faulkner, Sigmund Freud, Samuel Beckett, and the grave of Franz Kafka.

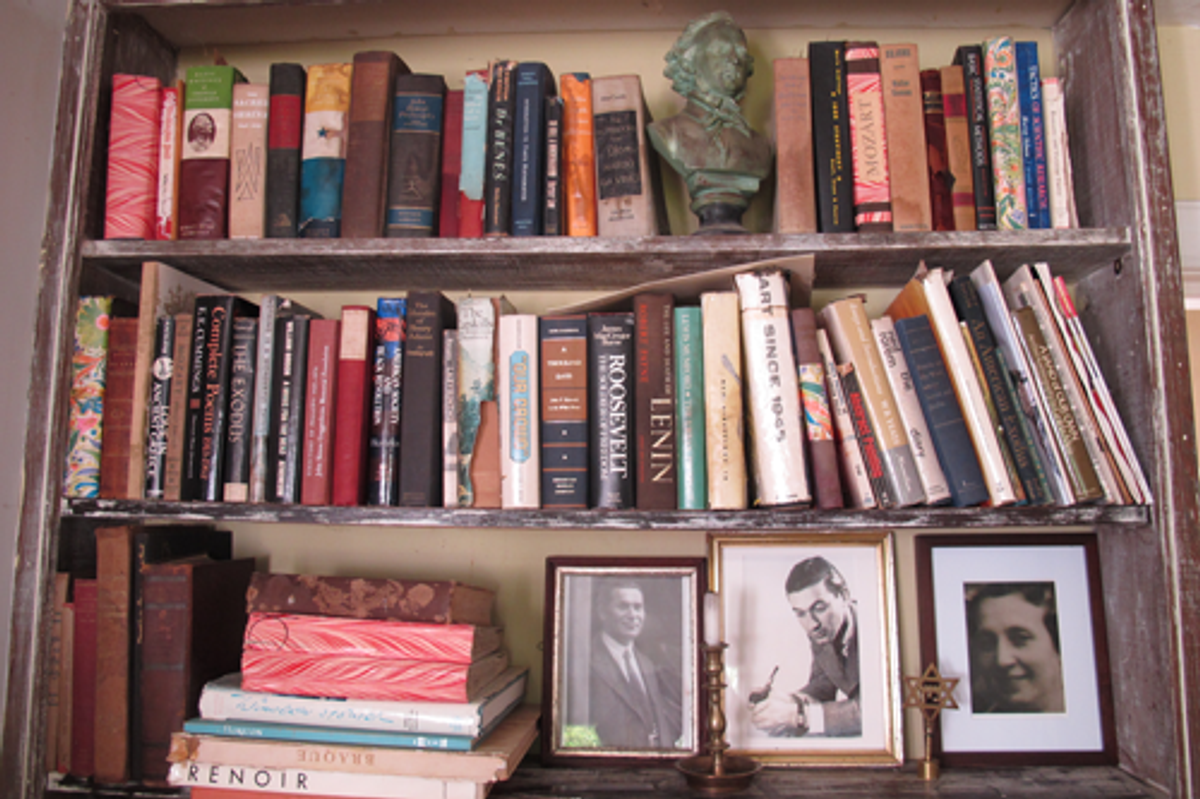

A bookshelf in the adjacent library was stuffed with books on history, religion, and art; on fiction, poetry, and philosophy. Beside the shelf, on a walnut mid-century chair, Pachner, I was told, listened to Mozart, whose pictures I saw all over the house, and to audiobooks, which he requested from the Library of Congress.

A bookcase in Pachner’s library displays photos of his parents and brother, who were killed in the Holocaust.(Photo: Louie Lazar)

“He has a phenomenal amount of mental energy, and he just has to absorb that energy into something,” Ned told me later. “It was directed into his painting, but when he couldn’t paint anymore, it was re-directed into his reading.”

In that chair, he voraciously “re-read” classic literature. Ann told me that Pachner kept notes with a felt pen, copying down favorite quotes until he memorized them. While lying in bed at night, he quizzed himself on what he’d learned.

A quote that he recited often, by Samuel Beckett, goes: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Pachner shared his insights with others. Ever since leaving Florida, he and Murphy, a retired orthopedic surgeon, chatted by phone at length.

“I have had the most magnificent post-graduate course in the mind and the Western canon that you can possibly imagine—through a man who never went to college,” Murphy said.

During walks with his friend Dwight Harris, 95, Pachner spoke of philosophy while holding Harris’s arm for guidance. “He was a little bit above my head,” Harris said.

But they found a common bond: Harris’ first automobile had been a Model A Ford.

Pachner never mentioned to Harris any relationship between Pachner’s car and his childhood in Europe. But it was obvious, Harris told me, that Pachner “had put his soul into it.” Pachner’s initials had been emblazoned onto its side in yellow paint. An old-fashioned sign was affixed to the automobile that said, “America Needs Roosevelt.”

Now, Harris fixed up the car for Pachner and took him on rides throughout Woodstock. “He was thrilled with that,” Harris said. “And even though he couldn’t see, he knew where we were. He could tell by the way the car turned what corner it was taking, and he would say, ‘Oh, there’s a red barn over on the right.’ He couldn’t see it, but it was there.”

Last year, Pachner was invited to the Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park as a special guest. He dressed up in a navy blazer and posed for pictures in front of his framed Collier’s 1945 portrait of Roosevelt, and met the president’s descendants, who greeted him with hugs. Pachner cried in elation.

During our first hour of conversation, Pachner had been deferential and self-deprecating, and routinely cut himself off as soon as he sensed himself ranting. (“I’m wasting time by talking too much;” “Please tell me to shut up;” “But you don’t want to hear that;” “I am rambling;” “I hate to repeat myself—it’s a sign of old codgers;” “You are here for what you need, not for my blabbering, wandering, and meandering.”)

But by the second hour, he was riffing guiltlessly on a variety of topics, to which I listened with sincere and enthusiastic fascination. A common thread was his disdain for individuals who value selling, status, and deception over authenticity, art, and the truth.

On what makes a true artist, he said: “You either have it or you don’t. And you cannot acquire it by quote-unquote studying under somebody, which is a joke because you’re going to end up being a pitiful copy of his mediocrities.”

On his painting influences: “My work—the touch of the brush is nobody else’s. Not that I celebrate it—I don’t celebrate myself. But what an idiot would I be, to celebrate myself.”

On why he never joined a college faculty in New York: “I couldn’t survive one faculty meeting. Because I have been to faculty meetings. They ask me to talk. It is too stifling, too confining, too imprisoning and a great harm to the spirit.”

On art historians and academics: “I have no use for them. They live on the blood of the creative individual.”

On work ethic: “All of those years, I produced. I am a worker. I am not a person that is a couch potato, you know?”

On his favorite quote: “Saul Bellow said, ‘Give all.’ I’ve been giving all; I am not bullshitting you. What do I want at my age? Reputation? Fame? What will it do for me? Could I sell you something?”

On finding completeness: “Your mature, productive—creative, in my case—self is brought forth by your youth. Those are your beginnings and to those beginnings, you must return. If you don’t, of course, you are going to be a very chaotic being and will not find completeness. It is simply being faithful to how you are made, how you came into the world.”

On braggarts: “The people who have the least—they brag about themselves the most.”

On hell: “I have seen people reading The Wall Street Journal while listening to Mozart—in front of me, over my shoulder. To me that is hell. Not some kind of subterranean arrangement. They don’t know it. They’ll never know it. To them, there is heaven as a reward and hell as a punishment. Well, that’s their business. If they want to be infantile, it’s their choice.”

On Happiness: “That’s a frivolous word. Frivolous. This whole country is built on this notion of quasi-happiness. That everything will come out all right. We know it will not come out all right. It will be a series of losses punctuated by your demise. And when that comes, life has ended, kiddo. It has ended. Yes.”

On his mental state: “But the point is, I am still here. I believe I’m balanced. I don’t think that I’m insane. At times I think I do. Everybody—we all do. But those are momentary and fleeting occurrences.”

On his peers: “Nobody that I knew personally, if they are older than I am, would be alive—it’s impossible. If they are my age—well, they wouldn’t be alive. That’s ridiculous.”

“My task is, I have been given the greatest thing, the indescribable thing: a life. Cherish it. As long as it lasts. It will end. Accept it. That’s the way it is. And will be. And has been.”

On the Friday before Thanksgiving, Pachner awoke at 4 a.m., earlier than usual. He enthusiastically requested soft-boiled eggs and coffee—typically he drinks tea.

On a nearby shelf were framed photographs of his parents, of his brother smoking a pipe, of Lorraine and his children, and a bust of Mozart. Sunlight entered through the windows, whose interior ledges were decorated with red-orange geraniums.

While he was waiting, he began to sing Mozart’s Requiem. In its Latin, he sang passionately. It begins:

Grant them eternal rest, Lord,

And may perpetual light shine on them

After eating, he continued singing Mozart, then went back to bed. Shortly after he awoke a few hours later, Nana went to prepare him tea.

When she returned, Pachner was dead. It had happened around 11:05 a.m. He was 102-and-a-half years old.

When she found him, his right hand was touching his cheek, and he was smiling.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Louie Lazar is a journalist living in New York. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Grantland, and the Jerusalem Post.