All the Answers

Michael Kupperman’s revealing graphic novel—or comic, depending—brings to life a repressed, brainy postwar American Jewishness that whiz kids like the Oppenheimer brothers can relate to

Dear Dan:

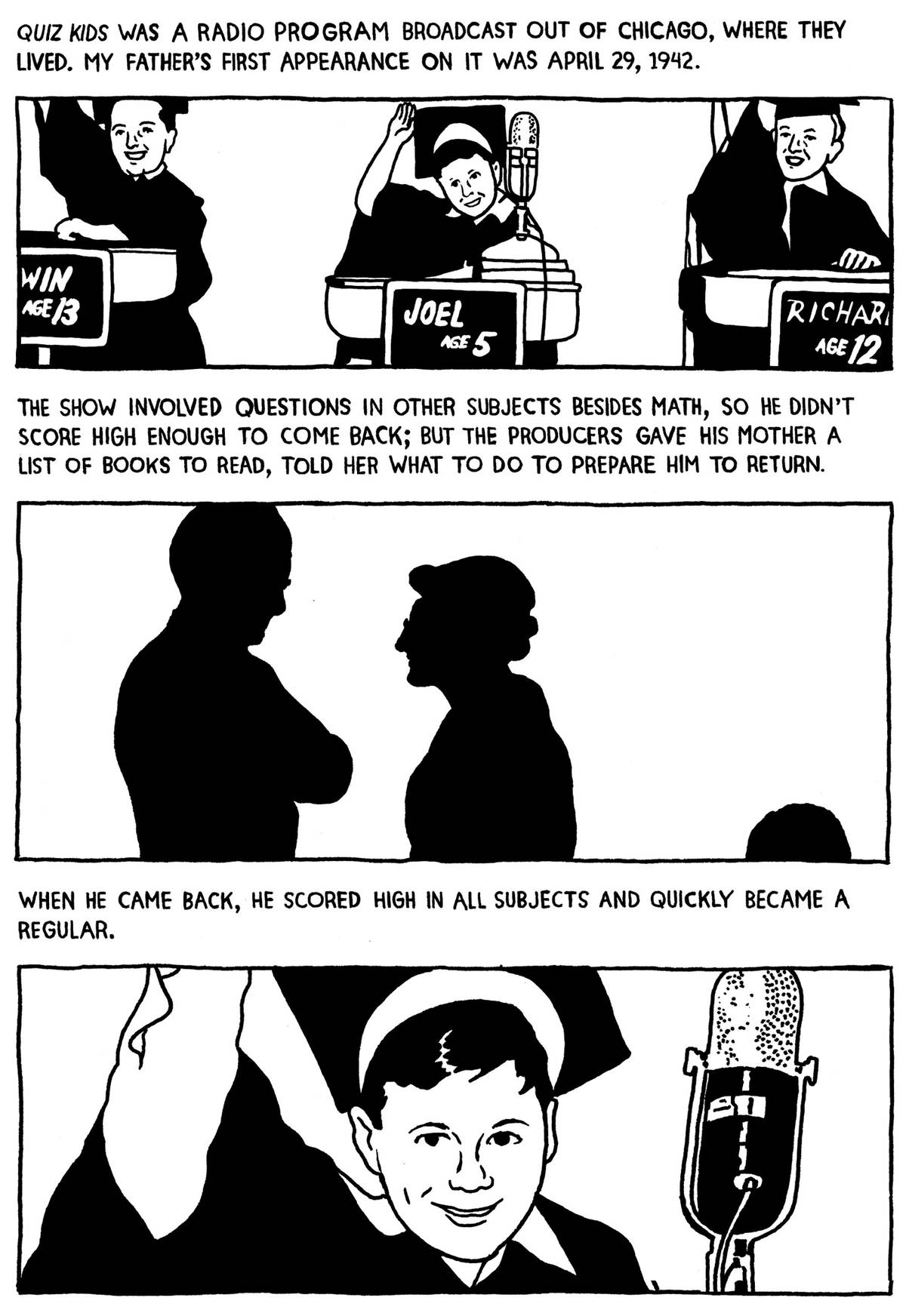

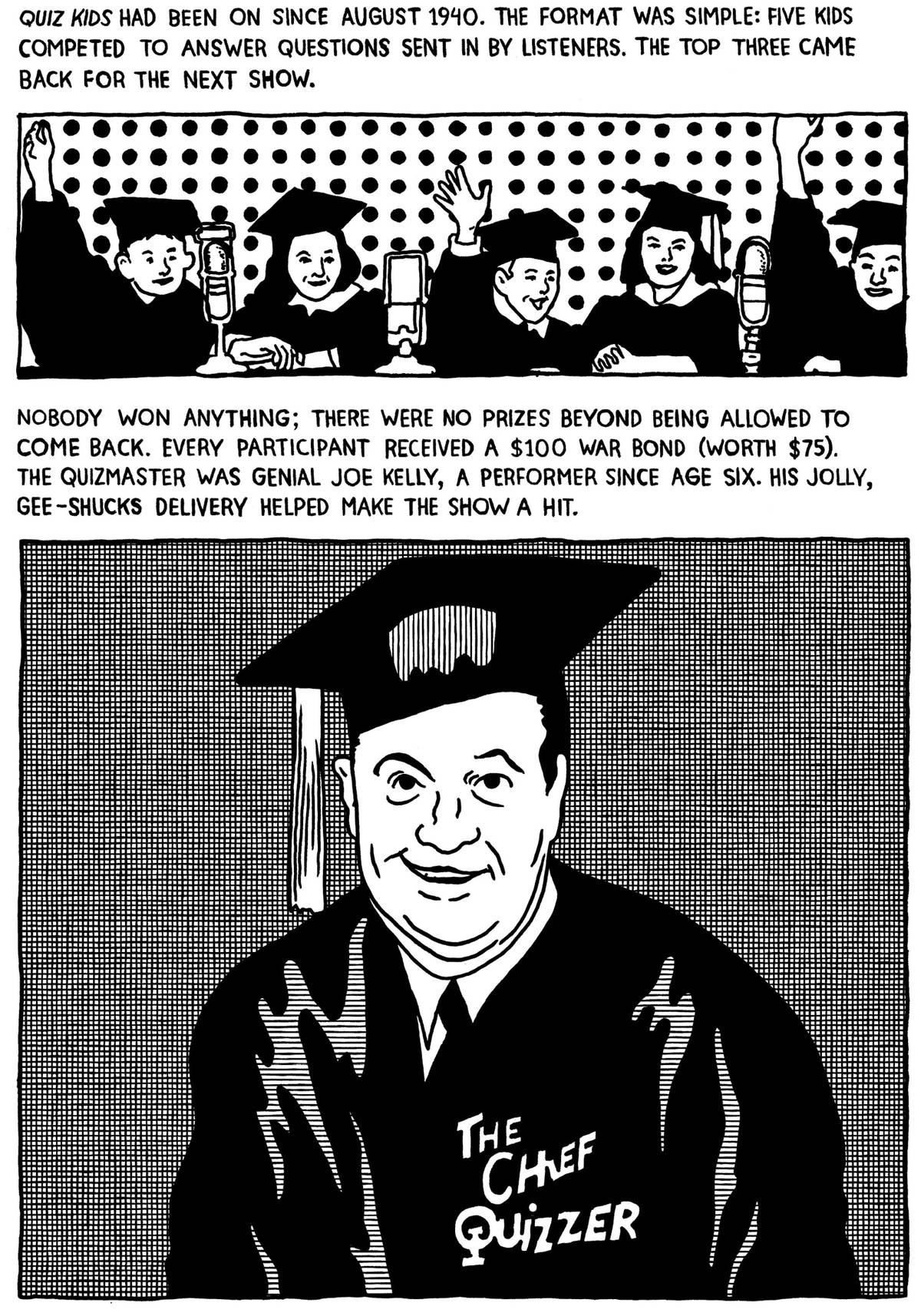

I mean, I just had no idea. Did you? Apparently Joel Kupperman, the subject of son Michael Kupperman’s new comic (as I gather graphic novels and memoirs are now being called), was one of the most famous people in the United States from roughly 1943 to 1954, the years when he starred on radio and then TV as one of the Quiz Kids. He was a math prodigy, or at least a fast-computation prodigy; he was extremely good at solving word problems, mailed in by the audience, but eventually he abandoned the field and became a philosophy professor.

So the first wow of All the Answers, for me, was a reminder of how much history escapes us, or is never with us; it’s not that Kupperman is only slightly remembered, like the vice presidential nominees on losing tickets. He is either easily remembered, by people of a certain age who thrilled to his and the other young panelists’ extraordinary feats of knowledge, or completely unknown. One pleasure of this tersely written comic, with its stark, inky illustrations, is seeing a nighttime ghost brought into the light of day. Kupperman was there all along, part of the radio days of our own parents’ early childhoods, but I had never seen him before now. Makes me think how much lives inside the older generations that we never get to see.

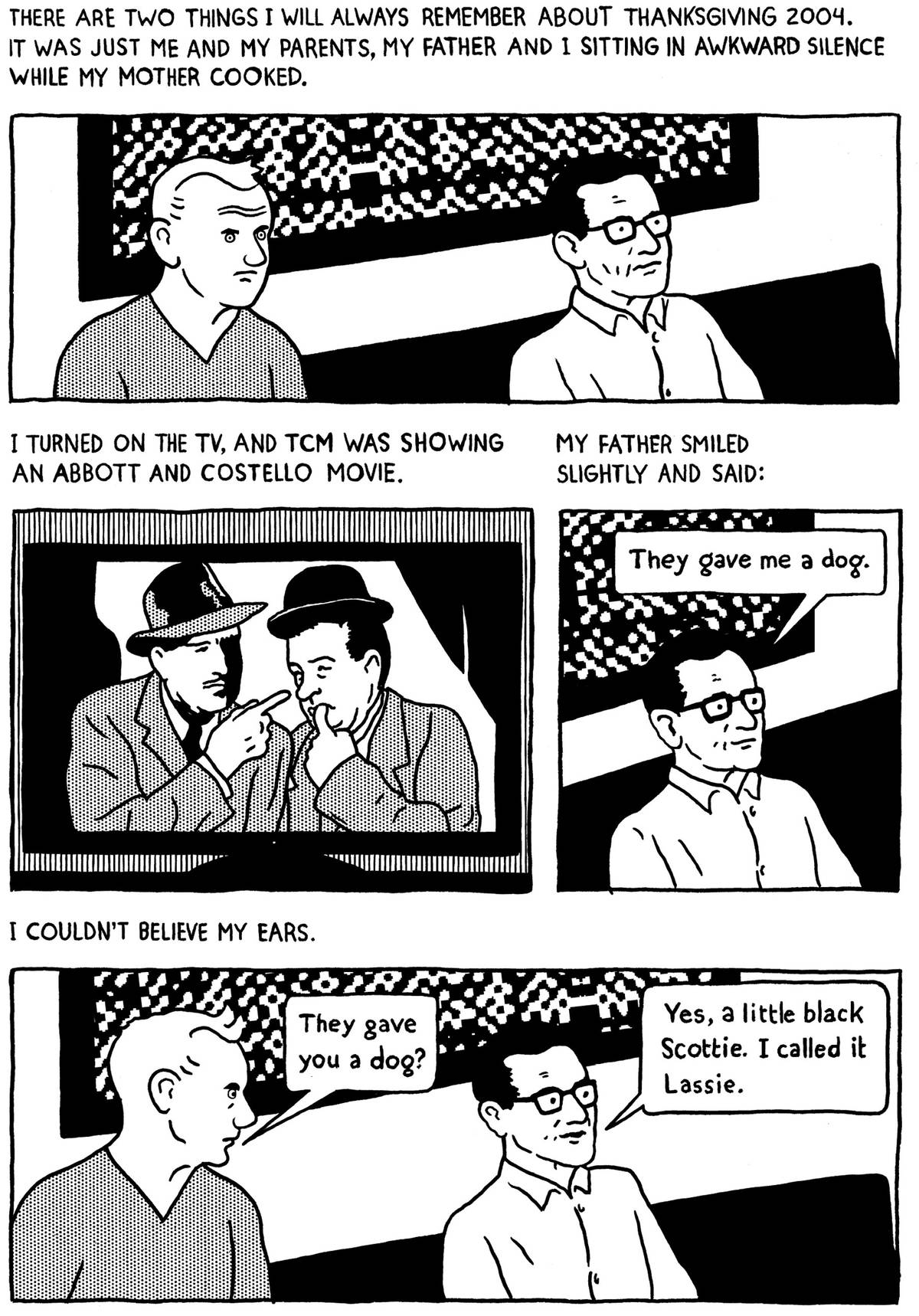

As we both now know, Kupperman was bullied into trading on his gift by a neurotic stage mother, part Mama Rose, part Sophie Portnoy. She got him cast on radio’s Quiz Kids, which happened to be broadcast from their hometown of Chicago, and made sure he followed the show to television. The quiz kids toured the country, bringing smiles to the homefront during World War II and the Korean War, much as Shirley Temple had provided relief for the Depression-weary. The young cherubs met Abbott and Costello; Jack Benny guest-hosted their show; little Joel even had a bit part in a movie with Donald (Singin’ in the Rain) O’Connor. But while most of his fellow contestants left in their early teen years, he stayed right up until the moment he left for his freshman year at the University of Chicago. By then he had become a bit of a joke, a know-it-all and teacher’s pet of national infamy. His social skills arrested, his romantic life thwarted by his mother, he was ruthlessly bullied by classmates.

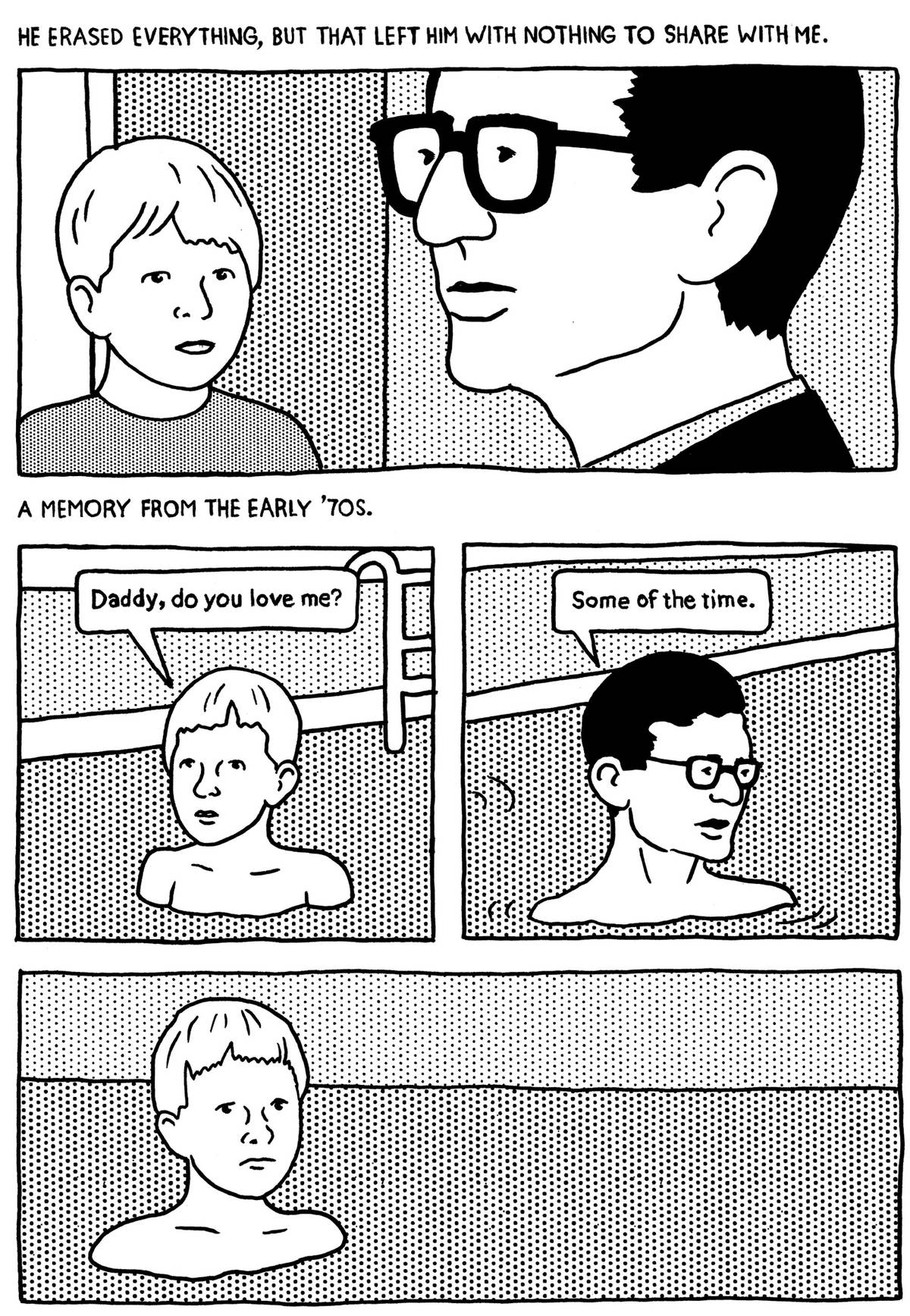

Our author and illustrator, Joel’s son Michael, knew very little of this until, a few years back, at the onset of his father’s dementia, he found his grandmother’s scrapbooks. He had a few chances to interview his dad before his mind clouded over entirely. And although his father, always disconnected, didn’t tell him much, he said enough to explain why Michael’s own childhood seemed so bereft of paternal love. His father, he realized, was a (highly functioning) trauma survivor. Michael’s exploration of his own past with his father is heartbreaking. When he asks his dad why they didn’t spend more time together, Joel replies that “nobody suggested” that he do more as a father. “It just didn’t occur to me,” he says. This from a man whose most famous book is called Six Myths About the Good Life. He could intuit what made life worthwhile, but his mother had made sure he couldn’t enact it.

As history, this book falls short. Kupperman gives Henry Ford far too central a role in the spread of American anti-Semitism, and he gives Judaism too central a role in Quiz Kids. In his potted history, Louis Cowan created Quiz Kids, and sought out a cute young Jewish star, as “propaganda” in a “struggle for the survival for the Jewish race.” After all, Kupperman asks, “Why else would a fairly cute kid with impressive math skills become such a national obsession? … Only if he’s Jewish, and it’s World War II.” But the war hardly created a vogue of philo-Semitism; to the contrary, isolationists blamed Jews for the war, and Jews played down their ethnic particularism, and besides, the full scope of the Holocaust wasn’t clear to most Americans until the war ended.

But the book diverted me, and I have to say that I can’t stop thinking about its closing pages, with their panels of Americans across the world, gathered about their radios, listening to Quiz Kids: in wainscoted libraries, in hospital rooms, sitting around a middle-class den, during a lull on the war front. That series of images, so homely and modest, really moved me, in a way that I don’t think words alone could. They made me realize why this had to be a comic.

So here we are. I think that of all the books that you and I have discussed over the years, and there must be hundreds, none of them has been a comic. As I type those words, I can think of one possible exception—I remember some conversations about psychoanalysis and attachment theory that may have been prompted by Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?, but maybe they weren’t; I do think we both read that book though, right? We have never talked about Maus (which I have never read), never talked about the kid-lit graphic novels of Raina Telgemeier, which I suspect your daughter has, like my daughters, read and enjoyed. So the question I leave you with is, what does it matter that All the Answers is a comic?

It’s a good place to start this dialogue of brotherly love because you, unlike me, read comic books as a child. Being a solipsistic older brother, I was not aware how much my two-years-younger brother read comics—how much of your time did they take up, relative to your voluminous sci-fi and fantasy reading? You surely feel the genre in your bones in a way I don’t. So I think that you will have a much stronger sense of how much this book achieves, artistically, in this hybrid form.

Yours,

Mark

***

Dear Mark,

I’m going to keep calling them graphic novels until it becomes more mandatory that I need to do otherwise. That article you mention, on why we should be saying “comics,” is unpersuasive. Or rather, it is persuasive on some of the problems with “graphic novel” as a catchall descriptor for the works in this medium, but unpersuasive that we should or can unring the bell and go back to using “comics” as the general rubric. The term graphic novel took hold not just because it gave advocates a strategic language for legitimizing comics as an art form, but because works like All the Answers really are different, in some meaningful ways, from most of the superhero comics I read as a kid, and the phrase “graphic novel” is good shorthand for signaling the difference. They’re longer than a serial comic. They’re bound differently. They often (though not always) have more literary ambitions. They’re marketed and sold differently. They have different beats, and different internal structures. They tend to deploy different visual styles, and often have different aesthetic lineages. Saying we should call them comics because they all share the same constituent materials is like saying we should call movies “television” because it’s all people in front of a camera acting.

I understand the technical objections to the term, but living languages don’t respect our technical objections. They select for utility in a brutal Darwinian fashion, and “graphic novel” is still necessary, among other reasons, because graphic novels like All the Answers come to us with a lot of these questions of genre and justification worn on their skin in a way that novels, biographies, and just plain old superhero comics don’t. You write, “What does it matter that All the Answers is a comic?” It strikes me that you wouldn’t ask that question if it were a novel, prose memoir, or a superhero comic. It’s precisely because it’s a graphic novel that you’re nudged to ask that question.

Before answering, though, I should cop to the fact that although I did spend a few years voraciously reading comics when I was a kid, I ditched them fairly quickly once I realized that fantasy and science-fiction novels existed, were available at the library, and were easier to persuade our parents to buy for me. What mattered to me, in comics, were the fantastical, good versus evil stories, less so the visuals. It made much more sense to me, once I did the math, to spend five or six bucks on a 600-page novel that hit those same narrative buttons than one dollar on a 30-page comic that took 10 minutes to read. But of course that was only the case because I didn’t appreciate the genre in my bones. The visuals didn’t sufficiently elevate or transform the stories for me, so I didn’t give up much in moving over to prose.

I can think of a few exceptions. The series Crisis on Infinite Earths has stayed with me. Chris Claremont and Frank Miller’s Wolverine miniseries, which I read as a bound graphic novel, was pretty amazing. Neil Gaiman’s Sandman collections. Maus, obviously, though I read that as a teenager, after I’d mostly left comics behind. There are stories that are unimaginable as anything other than comics.

But did this particular story need to be a comic/graphic novel? Comic art is the main skill that Kupperman brings to the job, so in that sense, yes. There was nothing else he was going to create. But did the story benefit so much, or rather so distinctively, from its visualization? I’d say no. I can imagine this story being told by a skilled writer, as one of those long memoiristic essays that The New Yorker sometimes runs, with roughly the same effect. Michael Chabon would write it well. Or Susan Faludi. Kupperman is a skilled artist, and he deploys a lot of different visual styles to tell the story, but on a deeper level the basic visual idiom seems to be the one we’ve already internalized from so many other midcentury American narratives. Newsreel footage. Old photos. People in mid-century clothes, in midcentury ticky-tacky spaces. I’ve seen this movie before.

I keep comparing the experience of seeing/reading All the Answers to what William H. Macy did as quiz kid Donnie Smith in Magnolia, a role that may have been loosely based on one of Joel Kupperman’s fellow contestants. That performance was revelatory. The combination of Macy’s acting with Paul Thomas Anderson’s dialogue brought into the world a character that hadn’t quite existed before, told a story we hadn’t quite heard before. All the Answers isn’t bad. I didn’t know anything about the world or popularity of Quiz Kids. Kupperman does a reasonably good job of giving us that history. There are moments of genuine poignancy in his father’s personal story. It moves along. If I weren’t committed to reviewing it with you, though, I don’t think I would have made it to the end.

I’m going through Kupperman’s book now, looking for visuals that did much more than just translate the text in a pretty linear way, and they’re few. On the page about his father’s “weird, staged publicity photos,” there’s something appealingly pervy about his rendering of his father as a naked young boy in the bathtub, bare bottom exposed. Kupperman’s few drawings of Marlene Dietrich, one of the many celebrities with whom Quiz Kid Joel Kupperman had awkward encounters, pop off the page. The two pages on his father being humiliated by his college roommates was gut-wrenching. I can find a few more standouts, including those closing pages you mention, but it’s not enough to carry a 200-plus page book.

What’s interesting is that all you have to do, to see that Kupperman is capable of more dynamism, is browse a few pages on Amazon of almost any of his other books. He is a funny, sexy, fascinating artist/writer. All the Answers is pretty drab by comparison.

Do you really disagree? If so, I’m open to being persuaded. I’m also interested, though, in delving more into what you said about the relationship between Jewishness and Quiz Kids. You write:

… he gives Judaism too central a role in Quiz Kids. In his potted history, Louis Cowan created Quiz Kids, and sought out a cute young Jewish star, as “propaganda” in a “struggle for the survival for the Jewish race.” After all, Kupperman asks, “Why else would a fairly cute kid with impressive math skills become such a national obsession? … Only if he’s Jewish, and it’s World War II.” But the war hardly created a vogue of philo-Semitism; to the contrary, isolationists blamed Jews for the war, and Jews played down their ethnic particularism, and besides, the full scope of the Holocaust wasn’t clear to most Americans until the war ended.

I agree with you that Kupperman’s handling of this stuff is pretty clunky, but I had a somewhat different reaction to his argument here. Isn’t it possible that the Jewishness of many of the contestants played some kind of role in the show’s popularity, in the way, say, that some of the popularity of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, in recent years, is likely the product of our cultural fascination with, and fear and loathing of, South Asian immigrants?

Yes, the cultural vogue for Jews didn’t really kick in until later. Yes, most people didn’t know all the facts of the Holocaust, and many blamed the Jews for irritating Hitler into war. But isn’t one of the brilliances of the American popular-culture industry precisely that it can take subjects around which there is great accumulated charge, often negative charge, and transmute it all into something people want to watch or read or listen to? From this perspective, isn’t the enmity that Kupperman says he encountered, from the masses as well as from classmates, just part of the brew?

Or maybe not. Maybe the show was popular for other reasons, and the Jewishness of the contestants was just an incidental product of the fact that the Jews—the Asians of their day—were better at the school thing. One of the books Kupperman relies on for his history, Quiz Kids: The Radio Program With the Smartest Children in America, has some evidence to this point: “Lou [Cowan], especially sensitive to these matters, once asked [his assistant] Roby why all five Kids were Jewish on one of the programs. Roby had no fear about telling Lou the truth. She said, simply, it was because that week they won.”

Yours,

Dan

***

Dear Dan:

OK, if you give me permission to go back to saying “graphic novel,” that is more than good enough for me. “Comic” didn’t really sit right on the page for me. So that’s that. Except I’ll take this occasion to mention that more and more I am meeting college students, students of mine, who use “novel” to mean any book at all, even, say, a nonfiction collection of essays: one very literate young woman referred to Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem as “the novel we read this week.” I have puzzled over this error, which strikes me as so unlikely and bizarre. One possible explanation is that, for people who did most of their formative reading on smartphones, the categories that matter are not oppositions like fiction versus nonfiction, or earnest versus ironic, but long versus short, or “book” (“novel”) versus everything else. For them, maybe all this illustrated stuff is just varieties of comic.

Whatever we call it, I’m glad you confirm my hunch that this is not the graphic novel (or comic) at its best. I was a little afraid to say as much, which is why I landed on the one part of the book, the closing pages, where the art really did move me, where the black-and-white pictures were well-crafted to invoke what is, in my mind’s eye, a bygone black-and-white world. You point to some other visual highlights: the Dietrich, the bare-bottomed boy, and so forth. But otherwise, you’re right that it’s an underwhelming use of the form.

One problem is that Kupperman never really got the goods. Even before Joel, the father, was overrun by senility, he was a terrible interview, repressed and reticent and terrified of introspection. Kupperman the author gives himself a lot of grief for betraying his father by writing this book, but the truth is that he’s a model of filial piety. When writing about his father and grandmother, he basically sticks to what he knows or what he can reasonably surmise. Which is a gracious thing to do, but it keeps him, and his readers, far from the terror at the heart of his story. Especially given that his father is too far gone to read this book, Kupperman could have ventured imaginatively into his father’s psyche, rooted around in there, and returned to draw some pretty scary scenes.

Or even taken just a little liberty with scenes that he’s pretty sure he knows about. At its heart, this book is a twisted, deformed Oedipal drama, in which Joel Kupperman’s father is never really present, and Joel at a young age becomes his mother’s traveling companion and stand-in spouse, and, if not the family breadwinner, then at least its status-winner. But in order to emerge into manhood, however inadequately, Joel had to kill off his only relevant parent, his mother.

And so we read, on pp. 133-135, of the June 1952 alumni reunion, where Joel Kupperman, still a Quiz Kid at age 16, was forced to mix with 400 of the show’s alumni. “My dad had graduated high school and was set to attend University of Chicago, staying close to his parents. Still appearing on the show,” Kupperman writes. “What must that night have been like for him? Everyone else had moved on. They’d married, gotten jobs, had children. Entered the real world. Maybe that was the night he finally said, ‘Enough.’ Maybe that was when he finally stood up to his mother. I know it happened. Even if he blotted it from his memory long ago. It has to have.”

But surely Sara Kupperman did not let her son retire so easily. Her son’s career was her entire identity, and Michael Kupperman makes a strong case that his grandmother had never let her son’s feelings interfere with her own ambitions for him (which is to say, for herself). Whenever and however Joel stood up to Sara, it was surely a showdown for the ages, a Grand Guignol of overdue separation. I wondered why the author did not speculate, at least a little, about how that conversation went. It was not out of respect for his father’s dignity: Over the next few pages he shows him being pantsed and otherwise humiliated by his college classmates, and besides, standing up to his mother was, it would seem, the birth of Joel’s manhood.

I actually wondered if Michael’s refusal to show his father winning justice for himself was an act of aggression. After all, Joel was a pretty terrible dad, distant and on occasion mean. In one affecting series of panels we see young Michael fall down the stairs, start sobbing, and look over to his father—who looks up from his reading, registers his son, then goes back to reading. Elsewhere, in “a memory from the early ’70s,” Michael asks his father if he loves him. “Some of the time,” Joel replies. The lack of connectivity, the difficulty sensing what the people around him needed, the insensitive literalism, the obsessive ability to master discrete subjects, the aversion to touch: It seems pretty clear that Joel Kupperman has some Asperger’s-like condition, undiagnosed and unexplained to those around him. But that made it no easier for his son, who has written a book filled with pity for his father but too little for himself. He’s angrier than he’ll come out and admit, and he has a right to be. This book needed more rage.

I’m on the fence about the Jewish question. You wonder if “one of the brilliances of the American popular-culture industry [is] precisely that it can take subjects around which there is great accumulated charge, often negative charge, and transmute it all into something people want to watch or read or listen to.” In other words, was affection for the Jewish Quiz Kids a way of cathecting Americans’ discomfort with the grown-up Jews in their midst? Was anti-Semitism at large the engine for philo-Semitism at small? Yes, maybe. I began to think about the weird vogue for cute black boys in the early and mid-1980s, how much white people seemed to love sitcom munchkins like Gary Coleman’s Arnold and Emmanuel Lewis’ Webster, at a time when a lot of them mistakenly feared the specter of their barely older brethren, were disoriented by hip-hop, saw their politics disrupted by Jesse Jackson. How better, went the flawed thinking, to domesticate the black person—and insulate us all from charges of racism—than by having Mr. D adopt little Arnold and rear him on Park Avenue? What better diversion from the Great Depression than Little Orphan Annie living it up in the Warbucks manse?

There are, in fact, three orphaned Jews in this book, three little Semitic variations on Arnold and Webster. The first, of course, is Joel, who has parents in the literal sense but is never truly parented, not in the sense we all need and crave parenting. The second is David Hoffman, a boy who lost both his parents in Auschwitz but survived himself. After the war, the Red Cross helped him immigrate to the United States—and almost immediately put him on Quiz Kids as a pitchman. “Just want to say that I hope everyone will give to the Red Cross,” Hoffman says, presumably in heavily accented English. “They can help other people the way they’ve helped me.” It’s the saddest scene in the entire book, and it goes to your point about how we manage our anxieties about the minorities in our midst. We couldn’t save the Jews of Europe, but we can put a cute, young survivor in a tie and exploit him on national radio.

And the third orphaned Jew is Michael himself, whose parents cut him off from themselves and from the extended Jewish family. “I have no idea what it means to be Jewish,” Michael says, above a panel of himself being approached by a Lubavitcher Hasid inviting him to shake the palm frond for Sukkot. “Are you Jewish?” the Hasid asks. “No,” Michael says. For the Hasid, the answer is literally true, because Michael’s mother is not Jewish. For Reform Jews, the answer is false. For Michael himself, the truth or falsity of the answer scarcely matters. He has enough Judaism—barely—and enough of a father—barely—to make this book.

***

Dear Mark,

A few weeks I ago I told a story at Austin’s version of The Moth. The theme for the month was “Comment Section,” and I talked about my unrequited intellectual crush on Ta-Nehisi Coates, the low points of which played out in the comments section of his blog in 2011-2013. It was a good story, a solid B+ or A-. When it came time to close it all out, though, I didn’t know what to say. I dribbled off.

This wasn’t a surprise to me. I knew earlier in the day, as I was scrambling to pull it together, that I was going to end limply. I hadn’t left myself time to really own the story, so my choices were either to come up with something pithy and false to end it, or to leave it muddy. I chose the latter. There’s a case to be made for either choice, depending on the execution, but of course the better choice would have been to give myself enough lead time to truly bake the cake before serving it.

The nice thing about doing an event like this, however, is that it’s ephemeral. You don’t have to stop working once your story is told. I could take that story and keep working on it, deepening it, until it’s more whole. Then I could publish it somewhere, or tell the story at another event. In this case, though, I probably won’t keep going with it. It’s so embarrassing. The race issues are so tricky to negotiate. I’m not persuaded that what I’m trying to say is interesting enough to justify the effort.

Art is hard. Among the things that are hard, for those of us who try to make it, is figuring out how far to go with projects that seem like good ideas but are putting up serious resistance. Sometimes you realize you’re throwing good money after bad. Sometimes you need to keep fighting.

Michael Kupperman closes his novel with a few pages of reflection on his own motives for telling the story, and on whether they justify the work.

“My father,” he writes, “had a long and distinguished careeer as a philosophy professor. He wrote, he traveled, he influenced thousands of young minds. He did escape Quiz Kids. Now here I come dragging it all out again. So here’s the $64,000 question: Does this make me a good son, or a bad one? I think I had to do this. It’s not good to live in the past, but it’s not good to ignore it either. For myself, and my family. And for him too. The story needed to be told. Didn’t it?”

From the outside, as a reader, my answer to that question is no. It doesn’t rise to that level. And the uncertainty of that question mark is evidence, to me, of muddiness in the work rather than well-earned ambiguity. On the artistic field of battle, I think, he was defeated. But that’s not quite the question he’s asking, whether I need his book in the world, or you do, or art does. He’s asking if he needed to create it. And maybe he did. As a son, and now a father to his own son, he may have won something more important than an artistic victory. I hope he did. I didn’t love the book, but he does come off as someone fighting the good fight as a person.

The book ends, interestingly, with a poem by William Freedman. I have no idea who William Freedman is (was?). Even Google is a bit vague on it. He was an English professor at the University of Haifa, and a poet. Possibly he’s still alive. I suspect Kupperman doesn’t really know who he is either. But Freedman wrote a poem, once, that is sort of about Joel Kupperman (or Kupferman, as he calls him). It was published in the Antioch Review in 1985, and Michael Kupperman found it and reprinted it to end his book, as a kind of final answer to All the Answers. It’s a lovely poem. It’s such a lovely poem, in fact, that I’m going to give it to Kupperman, though it’s not really an organic ending to the book he’s written and illustrated. What the hell, I’ll give it to myself too.

The Greatest

by William Freedman

Who’s the greatest man who ever lived?

I’d say Joel Kupferman.

One time this roller skater

from the Jersey Jolters comes on stage,

grabs him underneath the arms,

spins his fragile body nearly 90 RPMs,

and while he’s whirling there before us all,

his skinny legs splayed out like sparking wires

(we’re praying for you, Kid),

Joe Kelly, with a teaser from a guy in Florham Park,

wants the cube root of 11 pi to the 27th power.

And before that Jolter hits his stride,

before Joe Kelly even glances at the clock,

before the Allies hit Bataan, he gets it.

Right on the goddamn nose.

I’m in Israel, now,

Row 21, Seat 7, Section K

in the Roman amphitheater in Caesaria

where Rabbi Akiva,

Heaven bless his memory and soothe his skin,

96 wrinkled butter-fleshed years,

was flayed alive

(the 7th layer brought the plebies to their feet)

for answering questions he shouldn’t have asked.

96 he could take it.

Even the flayer gave him a hand.

Now Barenboim’s up there with Ludwig’s 9th

(you know the place: where the tympani

and cellos fight it out),

and a great white gull

shot from the window of the hidden sea

just soared above the shell,

pounded wings to match those drums,

spread out like cellos at full bow

and just kept going.

Akiva, you were great out there,

and Danny, Ludwig, Nature too,

don’t think I don’t appreciate you all.

But oh my God, Joel Kupferman,

I miss you so.

Love,

Dan

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Daniel Oppenheimer is an author and director. Mark Oppenheimer is Tablet’s editor at large. They are related.