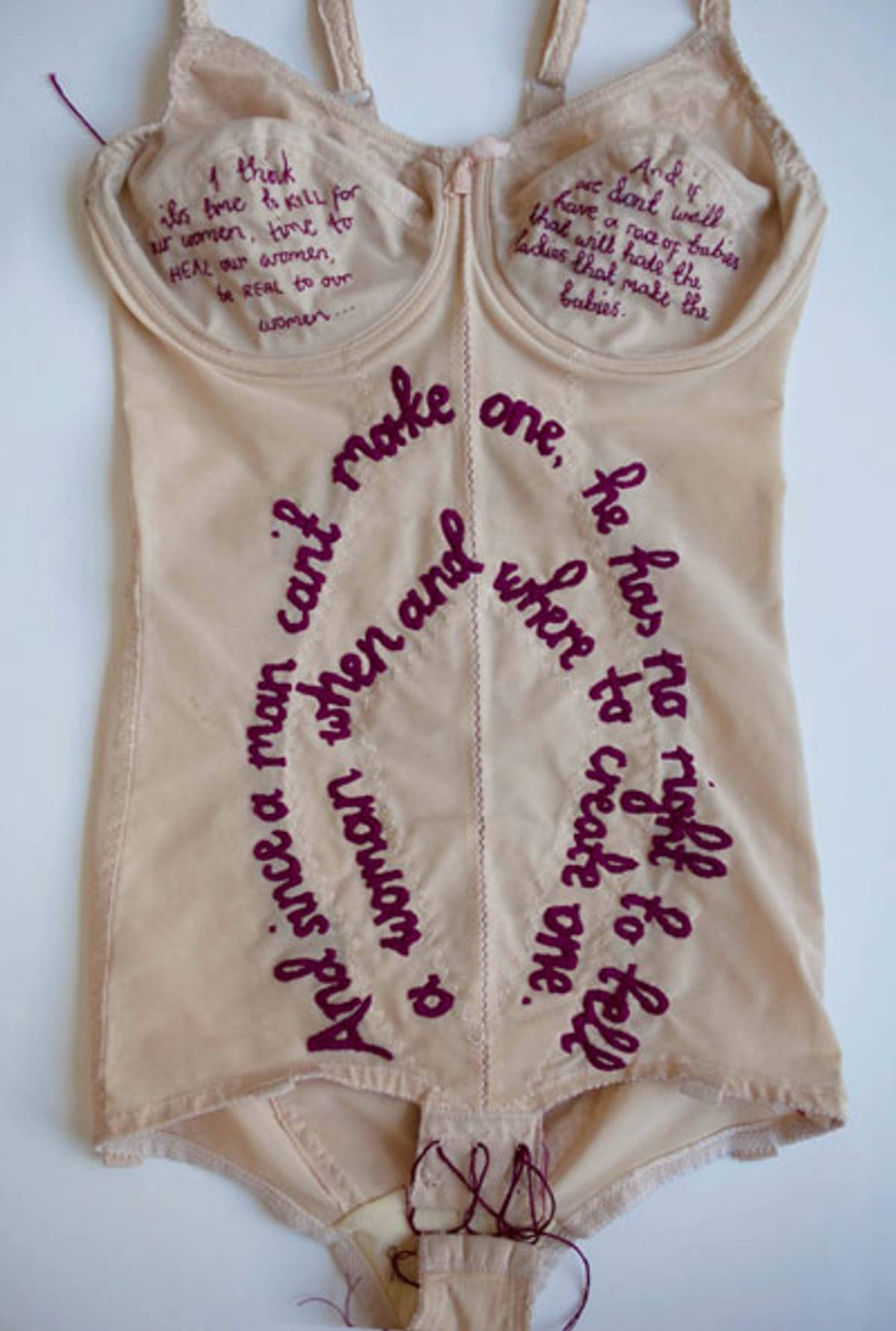

Tupac’s Corset

Artist Zoë Buckman describes how and why she embroiders late rappers’ lyrics onto lingerie

I had been wanting for a really long time to make work that explored the relationship between hip-hop and feminism in my life and in my upbringing. For me, “Jewishness” manifests within my humor, slang, cynicism, culinary tastes, and the spirit of generosity ingrained in me. But, oddly, even though I grew up in East London, I was immersed in hip-hop culture growing up, particularly in American hip-hop culture. Biggie and Tupac’s lyrics, specifically. I committed all their lyrics to memory and can actually recite them at the drop of a hat—it’s like my party trick.

The more I grew into my feminist upbringing the more I realized that I had a problem with some of the messaging in the music, which is an interesting dialogue that I wanted to explore. Then, when I became a mother, I found myself thinking about it again. I would never sing to my baby because I have a really horrible voice. In my sleep-deprived state in the middle of the night, I would bounce her up and down reciting Biggie and Tupac. When you’re cooing into the ear of your newborn daughter, “I got you pinned up with your fucking limbs up all because you like the way my Benz was rimmed up, bitch keep your chin up,” you’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, it really is time that I started working on this.’”

I don’t like to depict the female form explicitly, because I believe we see enough of the women’s body in art, film, fashion, advertising—every single industry out there exploits women’s bodies in some way, and I don’t really want to further that with my art. But I did want to find a way of evoking the female form, so I was looking at lingerie and underwear because obviously it speaks to sex, intimacy. We wear those pieces close to our bodies. So, I pictured having Sharpie-ed or spray-painted all the lyrics that referred to women onto the lingerie.

Then I started to think about bringing history into this work. And, instead of speaking to women, now, today, I wanted to evoke this idea of the lineage of women. But the more I thought about Sharpie-ing, cutting, or spray-painting these lyrics onto vintage lingerie, the more uncomfortable I became with that way of expressing it because it felt too overtly violent. The act itself would be making a comment on hip-hop music that I don’t personally believe in. I don’t blame hip-hop for misogyny in our society, per se. I don’t think you can just be like, “Oh, OK, it’s the black men, it’s the hip-hop, let’s just put all the blame there.” That’s not where it started. So, I didn’t want to do that.

I don’t like to shout out loud with my work; I like to get people to come in close. So, embroidery felt like the perfect way to do this, and obviously just the act of embroidery is very rooted in feminist expression through art and also in women’s daily lives throughout history. You know, the women gathered together and sewed the shrouds and the veils, and I felt like it just kind of made sense for this work given the fact that these two men have passed away and all these women who wore these pieces, originally, have perished.

I first started to collect pieces of lingerie from the 1920s and ’30s because I wasn’t thinking about any other eras, and I just had that visual image of it all being very floaty. So, the first piece I made was a pair of silk tap panties, and that felt good, and I was pleased with how that piece turned out. But then I stumbled upon more 1950s garments, which were made of Spandex, like this one, which is from the 1950s and which I found on eBay. I got the thread from this store called Purl in Soho, and I love it, it’s just for embroidery and knitting. It’s beautiful. You go in there and you’re like, aaaaaaahhhhh. I particularly liked the aesthetic of this piece because it was so restrictive, and it was the first time since the corset that wires and contours were coming back into lingerie. Visually, it holds up really well as a piece of art; there’s a real strength to it. This was actually the first piece to sell from the series, and it is one that people seem to most want to discuss or share. I think there are feelings of simultaneous sadness and strength connected to this piece. I’ve tried to find this one again, and of course you can never find the same piece twice.

I selected the piece first, and then I looked for the lyric I wanted to marry it to. I selected all the lyrics that Biggie and Tupac created that refer to women, and those are all on a Word document, split into Biggie ones and Tupac ones. And then I began highlighting the ones that I found most powerful—either really uplifting, misogynistic, or expressed some kind of duality, and then I would select the garment and be like, OK, well, this was something that was worn over the stomach. Then I would look back at the lyrics and if I saw something that referred to pregnancy or the gut like, “Hit you with the dick, made your kidneys shift,” I’d be like, “OK, this needs to go over there.”

Quite a lot of the pieces are an expression of me having fun with the practice, putting words that refer to breasts on bras or hoes on hosiery. And then other pieces I try and see if I feel like the garment has a story—for some of them, it’s more intuitive; I think about who she was and what she’s been through, the person who wore the garment. Often they’re stained or worn out in a particular part that was stressed over time. So, I like to think about the stories of these women and then find some text that marries nicely to that.

In vintage lingerie you don’t get a lot of black or red, that’s more of a modern thing, and the pieces that were darker were for prostitutes and are much harder to find.

There’s this one store in Chelsea that sells only vintage lingerie. I try not to buy too much there because her stuff is so expensive, but I found a piece and the owner, who is an old Jewish lady, actually, was like, “Well, ya know, this was faw ah streetwalkah.”

So, sometimes I feel like what I embroider is speaking to the woman who the piece belonged to.

Sometimes I start pieces and I’m like, no, this isn’t working and some of them just don’t make the cut; it’s not interesting enough. Alternately, for the corset used for “And Since a Man,” I saw the hooks at the crotch (something only present in the 1950s to 1970s pieces I have), and I felt it was an opportunity to highlight the discomfort of these garments, how they hold you in, how there is metal on such a sensitive area of the body. I also felt that the dark red thread was an evocation of blood, and about how the crisscross motion of the thread speaks to ideas of chastity and repression.

Also at Purl, I get these blue water-soluble pens, and I write out the lyrics first. I draw it out, then I get out my loop and I just start stitching. To be honest, I only use one of two stitches but because I vary the size and the color, it looks varied. You might want to pull it apart and just do two-ply if it’s a really dainty piece or, if I’m doing the satin stitch, I’d use the whole thing and stitch over and over and over again. This piece took three weeks, but they can take a few hours to a few months, so it depends. There have been times where I’ve found it meditative, but cranking it up for this show, I found the practice very stressful. The installation is everything—I really wanted it to be an installation you were forced to walk through, and I wanted to it be vast, so you would get this view of this sort of vast history of women and also really understand the breadth and depth of the artistic content of these two men.

Then there is the hanging, which is a bitch. You’re up a ladder with invisible thread, which is incredibly taxing on the eyes. I string fishing wire from the top of one wall to the next and create these lines that run parallel to the walls. And then, from that, the invisible thread, which is nylon, would come down from those. You’re up a ladder and if you drop that piece of invisible thread, it’s gone, forever. That’s why my new work is metal.

Interview collected, edited, and condensed by Periel Aschenbrand.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Zoë Buckman is a British artist, photographer, and producer.