The Brilliant French Catholic Literary Critic Who Revealed My Judaism

Campus Week: An important new biography of the late René Girard takes one academic back to the origins of his astonishment

The publication of Cynthia Haven’s full-dress biography of René Girard, a major figure in the “French invasion” that stormed the beaches of American academe across the final decades of the last millennium, marks a notable event on many fronts: academic, professional, literary, philosophical; and for some individuals among generations of students world-wide, deeply personal. In my case, that means religious.

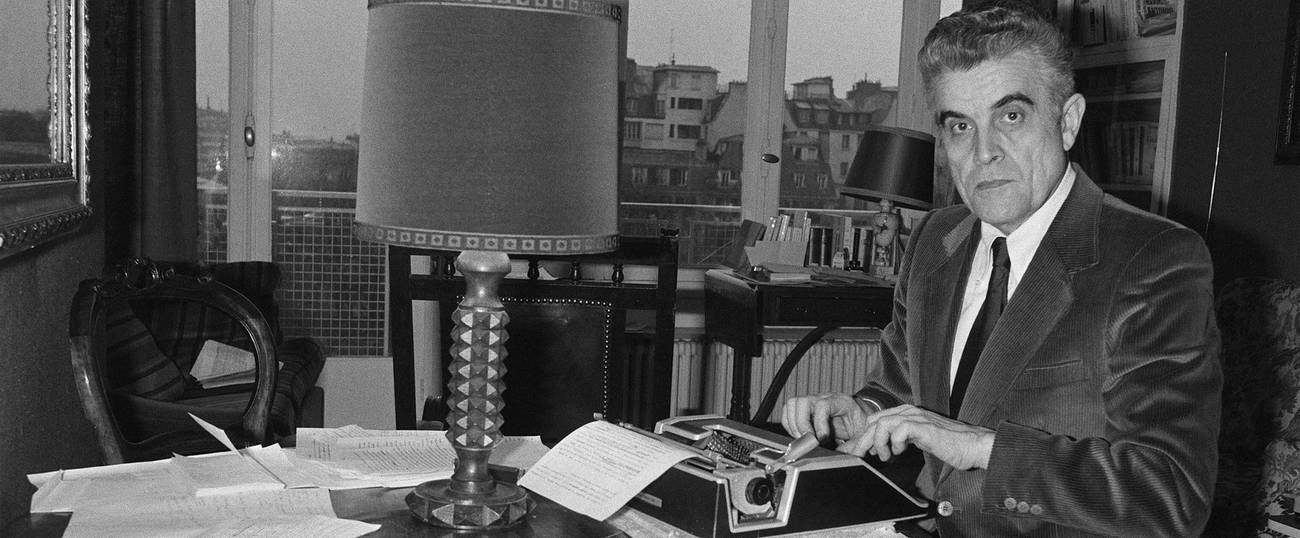

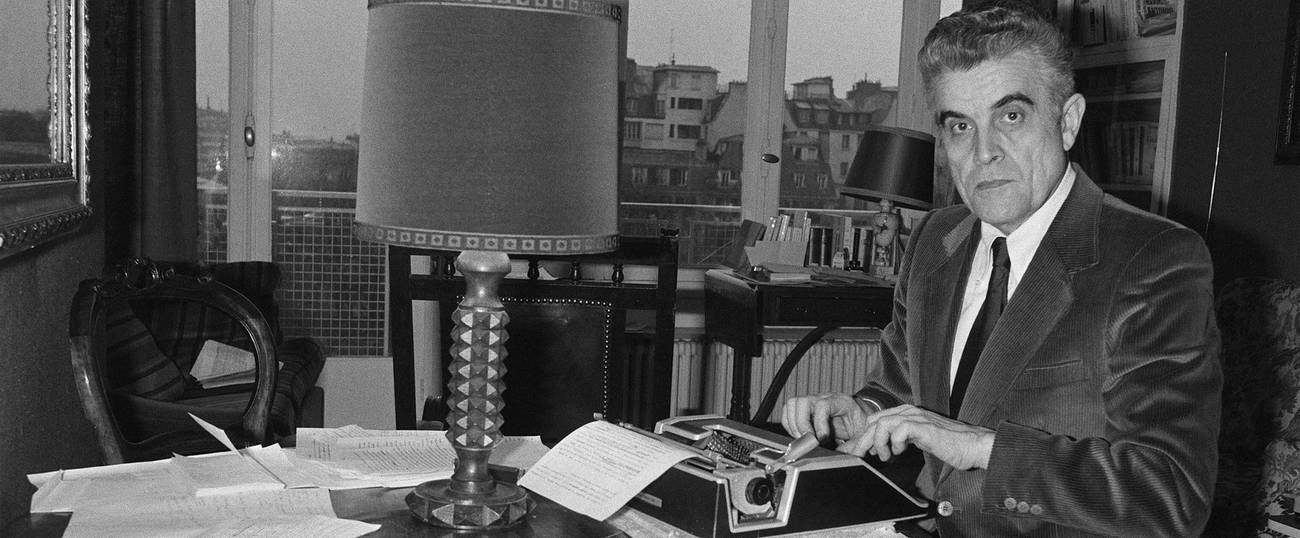

Thanks to a series of synchronicities that I will never fully grasp, I served for five years as Girard’s junior colleague, having earned my first tenure-track post as assistant professor of French at Stanford University (1988-93), where the brilliant Catholic thinker occupied a Distinguished Chair in the department of French and Italian, and influenced, among many other students, Peter Thiel. My subsequent decision—seven years and another university later—to become a Jew-by-choice was significantly informed by Girard, whose writings, colleagueship, and friendship informed the ongoing, gradual uncovering of the pre-existing Judaism that I had already intuited within myself.

During my five years at Stanford, having my office directly across the hall from René Girard’s and being able to hang out, have meals with him, and to sit in on his classes, I learned more about the Torah and Tanakh from him than I had from any other source.

Yet despite the intellectual, rational, and conscious influence of Girard on my thinking, writing, and teaching over a career now spanning some 30-plus years, I did not fully grasp his influence on my conversion to Judaism—how this happened—until today, reading Haven’s astonishing, just-released biography, Evolution of Desire. It’s an uncanny feeling, no doubt about it. But in order to trace how aspects or events in the life of one’s mentor can begin to appear to parallel or (uncannily) prefigure some of one’s own formative intellectual and spiritual experiences, some background regarding a single, previously little-known event in the history of post-WWII academe in the United States, is necessary.

Haven calls this formative event “the equivalent of the Big Bang in American thought.” It happened over the course of an international symposium called “The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man,” which took place at Johns Hopkins University in October 1966. “The event itself was René Girard’s inspiration,” she writes. It signaled the first tidal wave of the (in)famous onslaught of such high-profile (and much better known in the United States today than Girard) French theorists as philosopher Jacques Derrida, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, semiotician Roland Barthes, radical epistemologist Michel Foucault, and many others. Even today, this francophonic tsunami, considered collectively (and inclusively with such first-generation deconstructionist/feminist philosophers as Julia Kristeva, Gayatri Spivak, and Barbara Johnson), continues to shape curricula, faculty hiring, and pedagogy in the humanities, in ways that are now so deeply ingrained as to pass for a norm. By the 1980s most or all of these names would make up a virtually common syllabus of graduate studies in French, English, and most other modern languages and comparative literature departments, including where I was studying at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Understandably, the purported magnitude of an obscure academic meeting over a half-century ago may escape many readers today. So in order to provide an understanding of what Haven calls “the long thought,” contextualizing the life and times of her subject, she provides a thorough exposé of the substantive grounds underlying the conference and its stakeholders.

Haven states that the conference in 1966 “marks the introduction of structuralism and French theory to America.” At that time, she notes,

structuralism was the height of intellectual chic in France, and widely considered to be existentialism’s successor. Structuralism had been born in New York City nearly three decades earlier, when French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, one of many European scholars fleeing Nazi persecution to the United States, met another refugee scholar, the linguist Roman Jakobson, at the New School for Social Research. The interplay of the two disciplines, anthropology and linguistics, sparked a new intellectual movement. Linguistics became fashionable, and many of the symposium papers were cloaked in its vocabulary.

Haven’s lucid account of the theoretical throw-weight mustered by the symposium’s list of thinkers—not to mention the style points attributable to their egos and eccentricities—reveals a great deal of insight-in-hindsight, spiced occasionally with refreshing snark. (Jacques Lacan, for example, insisted that his silk underwear be hand laundered because “they were ‘fancy’ and ‘special,’” which elicited a gesture of scorn by the managers of the laundry, who were spotted “wadding them up and throwing them on the floor” by the graduate student who’d been charged with delivering said underwear.)

Unlike his distinguished conference invitees from Europe in 1966, however, René Girard had fled France and the French university system in order to make his career in the United States. By 1950 he had completed his doctorate at the University of Indiana, Bloomington, and by 1961 had risen to the rank of full professor and chair of romance languages at Johns Hopkins. At the time of the symposium, he had published (after a book of essays on Dostoevsky, and editing a volume of essays on Proust) his breakthrough study, Deceit, Desire and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure, which Haven calls “the book that would make his reputation.”

His initial concept—mimetic desire—signifies what he perceives as the force driving the triangular dynamics of attraction, envy, and jealousy in the novels under his lens. “At the heart of the book is our endless imitation of each other,” Haven writes. Emma Bovary, the bored provincial spouse of a boring country doctor in Flaubert’s eponymous masterpiece, has been so stuffed with images of torrid romance from her reading of bodice-ripping novels that she can no longer recognize herself or others around her; Girard calls the swooning heroines at the core of Emma’s reading her “mediators” precisely because she no longer connects her own wishes, desires, or erotic fantasies to any actual persons in her sphere; rather, she “projects” onto her callous, opportunistic seducers the exciting images culled from her reading—and the image of the risquée heroine onto herself. Thus, the desires she acts upon have been “mediated” by images conveyed to her consciousness by lazy, unguided reading of books one used to find under mattresses. In France, the phenomenon is so common that it has a name: “Bovarysme.”

While he neither trademarked nor monetized the term “mimetic desire,” René Girard followed its implications to previously undisclosed realms of insight in two other disciplines: anthropology (in Violence and the Sacred, 1972; first Eng. ed. 1977) and theology (in Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, 1978; first Eng. ed. 1987). In so doing, Haven writes, “he overturned three widespread assumptions about the nature of desire and violence: first, that our desire is authentic and our own; second, that we fight from our differences, rather than our sameness; and third, that religion is the cause of violence, rather than an archaic solution for controlling violence within a society, as he would assert.”

Haven stresses this divide—virtually an epistemological split, even as early as 1966—between René Girard’s theory of mimetic desire versus the language-structuralist emphases shared by most of the symposium’s other participants. I happened to become a direct beneficiary of his insight, decades later, living proof that the Body and the Book may share an inseparably positive ontology.

For as I later prepared my conversion ceremony, to join “The People of the Book,” I came to grasp the full, inner significance of these lines from Ezekiel 3.1-3:

… and He gave me … this scroll to eat …

and it tasted as sweet … as honey to me.

Haven addresses head-on the opposite question, of course, which was inevitably posed by his readers to Girard: Is mimetic desire always bad? She writes:

Imitation is inescapable—it’s how we learn, it’s why we don’t eat with our hands it’s why we communicate beyond grunts. When it comes to metaphysical desire—which Girard describes as desires beyond simple needs and appetites—what we imitate is vital, and why, and can be a symptom of our ontological sickness.

Yet Girard’s notion further reveals that the origin and eventual sublimation of blood sacrifice becomes an indissoluble truth linking anthropological reality to written texts, and bonding the life of the author to his or her works via his or her lived experience. Haven quotes Carl Proffer, her former professor and publisher of Ardis books of Ann Arbor, who once said: “Dostoevsky insisted that life teaches you things, not theories, not ideas. Look at the way people end up in life—that teaches you the truth.”

***

Although René Girard lived the majority of his life as a Catholic, that is not where he began. Because I worked with him only after he had become fully established in academe, I knew little about his earlier years. Like his, my early life was haunted by a specter of menace and violence: his, in the form of a Nazi conqueror and occupier ruling over his parents, his city and nation; mine, in the form of an undiagnosed, unpredictably raging father—an “autocrat of the breakfast table”—whose abusive moods and violence worsened as his two sons (my elder brother, who bore the brunt, and I) reached adolescence.

As in Girard’s case, literature became my refuge. My teenage years of intense, autodidactic reading in the Transcendentalists, Steinbeck, Salinger, Herman Hesse, and Dickens, only confirmed my unhappy life experience with organized religion in the form of small-town Protestantism. In my working-class household a variety of maternal love, virtually “Jewish” in the best sense, constituted the breadth and depth of any substantial religious endowment-by-example, beyond what I’d come to view as the fairy tales told by adults, to children, about the afterlife of Jesus.

When my mother began working outside the home, I was about 7; I was very fortunate, however, to be placed for daycare with the only Jewish family in our entire town, the Agranoffs—whose lively, loquacious household and dinner table felt to me like a visit to a Disneyland of wit, sarcasm, liberality, and laughter, in comparison to the buttoned-up, rule-bound Protestant board by which we humbly and almost silently fed at home.

By age 15 or so I’d become a deity-resenting atheist, continually shaking an invisible fist at the sky because of the outrageous suffering of sick children and the poor, permitted by a God that permitted evil and didn’t even exist. My burgeoning atheism then was similar, I now learn, to Girard’s as a young man. (I would have assumed that, like 95 percent of French youth of his time, he had been raised a practicing Catholic. He hadn’t.) We both walked around with small, dark clouds over our heads, comparable to the ones worn topside by most youths obsessed with literature or philosophy at that age.

Haven’s account of Girard’s conversion—to Catholicism, over a period from 1958-59—brings to light his own telling of the experience, plus several accounts of the time as remembered by friends and colleagues. “A radical debunking can bring one to the precipice of a conversion experience,” she states, “or something akin to it.” Girard tells of his attempt to finish the final chapter of Desire, Deceit and the Novel. While writing this “Conclusion,” he says that he “was thinking about the analogies between religious experience and the experience of a novelist who discovers that he’s been consistently lying, lying for the benefit of his ego, which in fact is made up of nothing but a thousand lies that have accumulated over a long period, sometimes built up over an entire lifetime.”

Girard found that “he was undergoing the same experience that he had been describing in his [Conclusion] to his book,” Haven recounts:

His experience changed everything, but perhaps the first thing it changed was Deceit, Desire and the Novel. … The authors, he saw clearly, were describing how they were being freed from their own mediated, ‘triangular’ desires. With that new understanding, they became their stories in a new way, with a wisdom previously inaccessible to them. The emergence from prison to freedom was the basis for the major novels he was reading, by Flaubert, Stendhal, Cervantes, Dostoevsky, Proust … but the only possible response he [René Girard] could have was to live out the same narrative in his four-dimensional life through time—just as the authors he had been writing about had done, after finishing the last pages of their own novels. That was the ending after the ending.

If the mediator is most often redundant and misguiding, why not adopt the lessons of the anti-mediator? As I came to see it in my own life, the critique of mimetic desire at the heart of Girard’s philosophy stems most directly from the “gift of the Jews” to the rest of humanity: the Second Commandment, which condemns idolatry. For just as conflict is sparked and spread by people desiring the same thing, primarily because others desire it as well, so is violence triggered within a community when exclusivity is implied by the physical presence of an idol. In a community of True Believers, what could be more desirable than the actual object embodying the deity? The Jews knew that Hashem could never be “located” or “objectified,” or else there would be no end to the kvetching. The Golden Calf is never a good idea.

After I left Stanford to “trampoline” to my next post, I landed at the University of Alabama, but not at the flagship campus in Tuscaloosa. Instead, I landed at the “tech” branch in the northern part of the state, in Huntsville, the city where Wernher von Braun brought his Nazi rocketeers to create the Redstone Arsenal and NASA after WWII. With this move, a rapidly resolved (thankfully amicable and childless) divorce, and two tenure-decision postponements, my supposedly hard-bitten existentialist persona experienced the kind of “radical debunking” described by Girard as the prelude to his conversion. I also underwent the onset of what (I would come to learn) psychiatrists call a midlife “kindling” of long-smoldering depression.

Alabama is not a good state wherein to find oneself in a depression. Intuitively, almost blindly reaching out, I reconnected by phone with a friend I’d known at the University of Washington. She was “half-Jewish” and had recently begun to deepen a sense of her own Judaism, attending services with friends, celebrating holidays, and digging into her Jewish father’s Ashkenazic background. Jennifer and I began to attend Shabbat services at the shul in Huntsville and, mirabile dictu, the rabbi in that formerly slave-trading Southern town—which had constructed its slave-auction platforms conveniently downtown because several rail lines intersected nearby—happened to be Steven L. Jacobs, a world-class Holocaust scholar and major mensch.

As I sat in Shabbat services in the beautifully preserved, century-old synagogue in Huntsville, Alabama, and began to feel the profoundest realizations of applied anti-idolatry move through my body, I relearned and incorporated the cultural import of both the Second Commandment and the memorably anti-sacrificial narratives (as René Girard had interpreted them with me) in the stories of Cain and Abel, the Akedah, Jonah, Job, and so many more. I realized that my first steps on the road to becoming a Jew-by-choice had already been taken.

Cynthia Haven’s mind-altering biography of this towering figure in 20th-century thought brings so much new information, and so many interpretive insights, that it’s hard to imagine any full-service public library, not to mention any academic collection, without a copy. The book is alive.

Which reminds me of a story.

Read more from Campus Week, when Tablet magazine takes stock of the state of American academia and university life.

James Winchell recently retired from teaching at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash.