A Pocket Book of Wonders

A remarkable record of miracles performed by Ya’akov Arie Guterman on behalf of simple folk in 19th-century Poland

Jewish hagiographies have constituted one of the profound genres of Hebrew and Yiddish literature since the late Middle Ages, although biographical tales devoted to prominent religious figures of Judaism may be traced as early as in biblical and Talmudic narratives. The spread of stories about the kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria of Safed (Ha-Ari, 1534-1572) established a canon of similar writings that became extremely popular among Ashkenazi Jewry in Eastern Europe. The Hasidic movement that originated in the Polish lands in the second half of the 18th century, and that to this day remains a thriving phenomenon throughout the diaspora and Israel, placed hagiography at the centre of its popular activity.

The publication of Shivchei ha-Besht with Hebrew and Yiddish versions of stories about the Baal Shem Tov (the alleged founder of Hasidism), paved the way for a rich literature that covered large volumes and short booklets alike. In his fundamental book The Hasidic Tale, Gedalyah Nigal indicates typical features of such narratives. The stories revolve around a wondrous act performed by the tsaddik, frequently resulting in resolution of a problem. There is only one protagonist, while other individuals, Hasidim or simple persons, appear mainly as his devoted clients. The tales take place in Jewish and non-Jewish environments, but descriptions of landscapes and nature appear only incidentally. Even in the beginning of the 20th century such literature continued to attract the interest of Orthodox readers and developed in accordance with modern standards of writing, editing and publishing. However, it took several decades before Shmuel Rothstein—a veteran fun der ortodoksisher prese—published in Warsaw his well-written books on the Tsanz and Sadagora Hasidic dynasties. This essay, however, will focus on a much earlier example of Hasidic literature, a “pocket book of wonders” of more traditional character, but nevertheless modern in its general utterance.

***

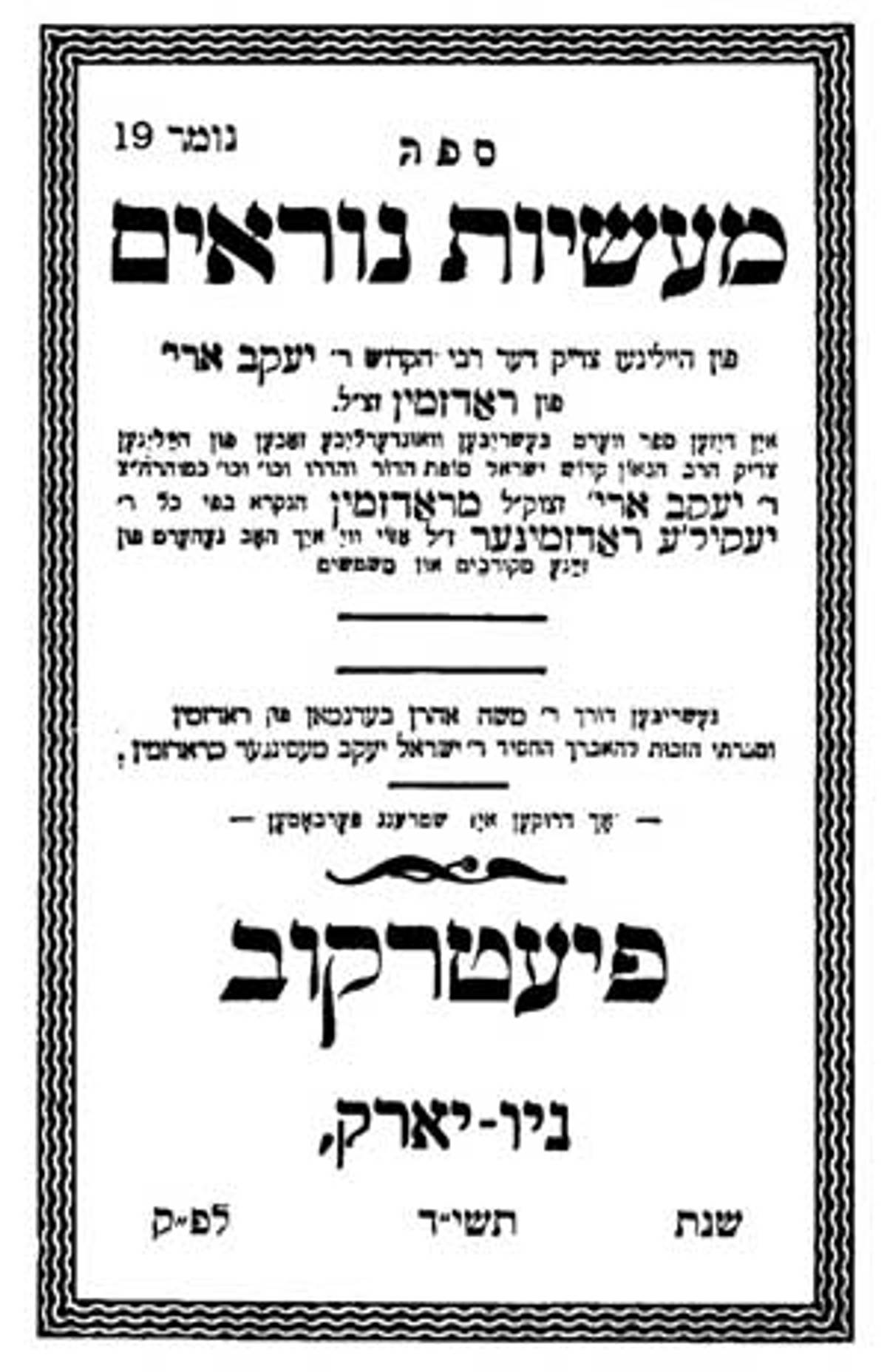

Mayses Noyroim (Hebrew: Ma’asiyot Nora’im, The Deeds of Awe) is a Yiddish booklet published in the year Tav-Ayin-Dalet-Resh (1913 or 1914) in Pietrkov (Piotrków Trybunalski), central Poland. It was the product of the publishing house of Avraham Yosef Kleiman, a native of Kołbiel (Otwock county), whose name appears on many original and illegal editions of Hasidic and kabbalistic literature printed in Poland at the turn of the 20th century. According to the opening page, this small-format publication of merely 41 pages was written by Moshe Aaron Bergman of Radzymin. In the late 1960s the booklet was photocopied and republished in Tel Aviv by another Hasidic publishing house, Pe’er ha-Sefer.

The work documents wonders performed by Ya’akov Arie Guterman (1792-1874), a Hasidic leader active from the beginning of the 19th century, also known by his popular name: Reb Yankele Radziminer. He was one of the most distinguished figures of the Hasidic movement in Congress Poland. His path led him through courts of renowned tsaddikim: The Seer of Lublin, The Holy Jew, Simcha Bunim of Pshiskhe (Przysucha), and Yitzhak of Vurke (Warka). The last two had the deepest influence on Guterman in his formative years. They represented a vision of scholarly leadership, critical toward material tsaddikism and its characteristic manifestation: wonders performed on behalf of simple folk.

Later Guterman established his own court in the town of Radzymin, about 50 kilometers northeast of Warsaw. Despite a rather radical ideological background, his fame as a miracle man spread widely across Poland and was reinforced by popular writings published after his death. He outlived most of Simcha Bunim’s direct students. The blessing of arichat yamim (long life) turned him into a zaken ha-admorim, an elder among Hasidic leaders, whose influence may be measured not only by the number of followers but also by age. Deeds of Awe is a collection of stories gathered by the author, Moshe Aron Bergman, to a large extent from the oral testimonies of local witnesses and those who participated in the court life. Bergman himself was apparently a Mashba”k at the court in Radzymin (Meshamesh ba-kodesh, literally, one who serves in holiness; a person who performs personal services for the Rebbe), probably during the tenure of the third Rebbe of the Guterman dynasty, Aharon Menachem Mendel. Besides sparse references to the ritual customs of the Radziminer, as well as a handful of his precepts, the text focuses on the esoteric dimension of the leader’s multifarious activities.

The pocket book starts with a testimony that Ya’akov Arie Guterman was a man of God’s prophecy and “everything hidden had been revealed before him.” Rebbe’s miraculous talents remained concealed for most of the time. Only his closest friends were able to sense “the scent of his incense” and become thus inspired to choose him for a leader. The introduction is followed by a short enumeration of Guterman’s most distinguished followers and apprentices in rebestve (tsaddik’s lore and duties): the two Hasidic leaders of the Alexander dynasty, Yechiel and Yerachmiel Israel Itzhak, the Admor of Gostynin Yechiel Meir, as well as Baruch Shapira Shtutsiner. The list is further supported by a testimony of Reb Eliezer Ha-Kohen, the Rabbi of Maków, Pułtusk, Płock and Sochaczew. In a manner typical of Hasidic hagiographies, it quotes a statement ascribed to the Rebbe of Kock (Kotsk) that there are two great tsaddikim in the world: the one in Radzymin and the one in Sochaczew. It is crucial to notice that both Menachem Mendel Kotsker and Avremele Sokhachever were influential leaders of their generation. Therefore, all the aforementioned elements of the introduction, the two testimonies and the list of remarkable students, were meant to present a picture of the protagonist as an important Hasidic figure, an outstanding link in the golden chain of generations.

The booklet then briefly recounts the story of Guterman’s life, to present his person in supernatural circumstances. It does this, however, in a rather restrained manner. Most of the individual voices registered here share doubts whether the unorthodox advice of the tsaddik of Radzymin is purposeful. Sometimes the path to salvation is full of obstacles: The tsaddik scolds his followers, throws them out of his room or simply denies them access to his cheder meyuchad (a personal chamber). Such circumstances are generally interpreted (not as paradoxical as it seems) as a sign of his favor.

Let us turn back for a moment to Guterman’s early years. According to the book, he was born in the town of Warka to a father who was a well-to-do mercer. Both parents were known for their piety and the charity they performed, virtues that generally characterized families of famous tsaddikim. The purity of his mother is emphasized by a comment that she would burn the sheets after every childbirth. As a young scholar, Guterman demonstrated exceptional learning capabilities and soon married a daughter of a rich householder from Ryczywół. When his father-in-law fell into debt, the local community offered young Guterman a rabbinic post with a modest wage. The worsening financial situation caused conflict between the protagonist and his wife, but salvation came soon with the help of his departed masters. One Rosh Hashanah, during the new-year service in the synagogue, he had a vision, in which the Seer of Lublin and the Maggid of Kozienice (another important figure of Polish Hasidism at the turn of 19th century) announced to him the changes that were coming. The same year he was offered a rabbinic position in Radzymin, a proposal that made it possible for him to become a Hasidic master and an influential leader.

This period of Hasidic history brought about a visible shift in the rules of inheritance. A growing number of tsaddikim were leaving their positions to a son, son-in-law, or grandson. The process of the emergence of great Hasidic dynasties had started much earlier. During the Napoleonic wars it was already visible in Ukraine and Lithuania, but in Congress Poland it developed with a delay of a few generations, in the second half of the 19th century. The most important followers of the Rebbe of Kotsk created their own courts by gathering a noticeable number of supporters around them. Again, most of them started separate dynasties this way. The lack of such holy ancestry was disadvantageous for the tsaddik of Radzymin. The more crucial was the meaning of his spiritual lineage. The booklet states that the moment he moved to Radzymin, Guterman was already known as a close apprentice of Simcha Bunim of Pshiskhe. According to one of the stories, the latter disclosed to him a secret name which enables one to be raised from the dead. However, Reb Simcha Bunim did so on condition that his young follower would never avail himself of the opportunity. When he eventually did employ it, Guterman suffered a serious disease, lying unconscious for a couple of days, until he woke up and described to his relatives the trial conducted against him by the heavenly tribunal.

The strength of the association between Guterman and his great predecessor from Przysucha is attested to by the narratives that follow: Every evening of Yom Kippur the tsaddik of Pshiskhe would send his follower from Radzymin a kvitl, which was quite a unique custom, a confirmation of the latter’s position as an autonomous leader. Whenever he had many visitors and needed help in receiving kvitlech, Simcha Bunim asked Guterman for assistance and stated that it is “all the same” whether the supplications are given to him or to his young counterpart. Another example of Guterman’s close relations with the Rebbe of Pshiskhe is a story in which the latter would travel to spas only with a group of his closest students. One year the tsaddik of Radzimin did not participate in this excursion, but nevertheless he could tell exactly where, when and how his master performed prayers or even smoked his pipe!

Less often, although in a similar manner, the book presents close ties between Guterman and the first Rebbe of Ger (Góra Kalwaria), Itzhak Meir Alter. According to one of the stories, the householders of Radzymin came to Chidushe Ha-Ri”m, as it was named after a title of his Torah commentaries, for advice regarding candidates for the rabbinic post in their town. The first Rebbe from Góra Kalwaria suggested they should speak with a young rabbi of Ryczywół. According to another story Chidushe Ha-Ri”m once sent him a pidyon, an obvious act of recognition of the protagonist’s status as a Hasidic leader. It seems interesting, however, that among the stories collected in Mayses Noyroim much lesser attention is accorded to Guterman’s last teacher and master, the Rebbe of Vurke.

Another authority who endorsed the holy status of the tsaddik of Radzymin was the Maiden of Ludmir. The author of the booklet devoted an entire page to remind the readers of a prophetic gift the only female tsaddik employed for the sake of Jewish faith. Following a story of an illegal marriage between a kohen and a grushe (a woman expelled by her former husband), the book quotes a testimony, according to which the Maiden of Ludmir described young Guterman as the one who runs around the house of prayer causing angels to tremble. It is interesting to notice that another woman, the protagonist’s own wife, also observed a flame dancing around him during prayer. However, the phenomenon disappeared just after she openly described her vision. This motif of feminine acceptance of the tsaddik’s holiness calls for further study.

***

When the stories finally focus on Guterman’s wonders, they generally cover three aspects of activity. According to the rules of material tsaddikism, reinforced by the authority of Elimelech of Lizhensk (Leżajsk) and the Seer of Lublin, a Hasidic leader is responsible for providing his followers with bene, chaye, and u-mezone: children, life (or health), and means of subsistence. Although this ideal would be later criticized by the Hasidic school of Pshiskhe, the three elements constituted fundaments of happiness and fulfilment of an individual in traditional Jewish society, and therefore remained important motifs of the relationship between tsaddikim and their believers. In Mayses Noyroim the group of those who may expect salvation by virtue of the blessing of the tsaddik is very broad. It includes Hasidim, who usually need to pass a test of faith to acquire the Rebbe’s support, but also people of lower moral status. According to the stories, Guterman helped a simple smith, a Jewish ignorant who took off his hat while visiting the Rebbe’s court, overcome his infertility, as well as a childless landowner’s wife (a Christian, Es iz do fil goyim, loz zayn nokh a goy). When on another occasion a Polish noble asked him to cure his mute son, Guterman did so by hitting the boy with a gartel. Suddenly the boy started to shout: “Tato, Żyd mnie bije!” (“Father, the Jew is beating me!” a phrase written in Polish with Hebrew letters)—proof that, regardless of its foulness, the child received the tsaddik’s blessing.

But the booklet also provides some intriguing details about Guterman’s weltanschauung. In the case of a woman who bore a child in the eighth month of pregnancy, he forbade her to speak about the infant as a nakhtl (an akhtl). Surely the tsaddik himself shared the long-lasting belief, very much dependent on the Ptolemaic system of the universe, according to which an infant born in the eighth month is extremely vulnerable (due to the influence of the planet Saturn). Even this rich catalogue of miracles does not prove, however, the tsaddik’s omnipotence. Once a follower brought him a supplication in the name of a childless brother-in-law, but despite intensive spiritual endeavours the case appeared to be hopeless. On another occasion Guterman had to choose whether he would help a mother, or the baby in her womb. The answer was: Az dos lebt, loz dos shoyn lebn (Let her live, if she lives already).

In order to perform acts of miracles, especially while healing the sick, Guterman was supposed to challenge the heavenly tribunal. This challenge assumed the form of learned polemics, but both sides of the trial could also resort to tricks and deception. Once he convinced the tribunal not to kill a man until he, the tsaddik himself, finished smoking a pipe. In the middle of smoking he put down the pipe and left the unfinished tobacco, so the man could live for long years. On another visit in front of the tribunal he scolded and drove away a pregnant woman, who was expecting a harsh sentence, and therefore saved both her and the child she was carrying.

Another popular motif appearing in most stories about 19th-century Hasidic leaders in the context of healing is the cholera epidemic. Against cholera, a disease that Guterman observed in the deadliest periods of its onset, he recommended an amulet containing the name of Avraham’s mother (Amtalai bat Carnuvu)—a common measure of practical Kabbalah. It would be inappropriate, however, to categorize this Hasidic leader as an individual hostile towards more sophisticated medicine. In a few different stories in the booklet he has been portrayed seeking the advice of modern physicians, especially in Warsaw, both personally or by sending his shames (servant).

The short pocket book abounds in testimonies of the tsaddik’s interventions aiming at ensuring the financial well-being of his followers. Guterman is depicted as a person who is free of the corruption which money usually brings. He has no idea about it: He is dependent on his shames and loves money as a child would, unaware of its true value. On the other hand, the Hasidic court in Radzymin apparently had quite strict rules regarding fees paid to the tsaddik for his attention. An audience cost 25 rubels and Guterman demanded the same sum from a childless smith, as well as from a broker whose cows were dying out. When a poor man tried to haggle a lower fee, the tsaddik told him that he had to pay 150 rubels and not a rubel less. Fighting for means of subsistence is a difficult task, states one of the stories, because since the Temple had been destroyed all of the world’s wealth lay in the hands of gentiles. Nevertheless, the tsaddik is ready to help Christians too, as was in the case of a Curland German guarding the Krasiński Garden in Warsaw.

According to Bergman’s sources, Guterman’s interventions on behalf of Jewish brokers were frequent, and local nobles told stories about an old Jew who visited them during their sleep. Such circumstances created occasions for utilizing his prophetic talents, as was the case when he foretold the death of a Christian suitor for a tavern lease. Once again, the tsaddik’s actions were not limited to demonstrations of spiritual powers. He engaged in negotiations between Jewish brokers and landowners, wrote letters and advised his followers to pay the nobility proper interest. A Jewish fisherman was once told by the tsaddik to fulfil all ritual obligations, especially the evening prayer on Thursday, because Jewish and Christian fishers would drink together on Thursdays. The effect was instant: The fisherman started to catch 800 rubels worth of fish every day. Over many years he amassed enormous wealth, but his luck changed as suddenly as before, when he forgot about the real reason for his fortune.

Apart from the three fundamental issues of children, health and money, there were also other, more or less typical cases, that found their way into the booklet. The problem of sholem bayis (peace of the home) is expressed in a story of a broker whose wife appears to be wiser than he could expect. Also, the problem of compulsory conscription is addressed in the stories where Guterman offers advice on how to avoid conscription or desert the army.

***

The order of the stories is deeply chaotic. With a few exceptions they usually bear no title and virtually no bibliographical references, which renders difficult the process of differentiation between testimonies gathered by the author and older traditions. Some of them have no clear connection with the protagonist. For example, a story told by “the current Rebbe of Radzymin,” heard from the grandfather of the third Radziminer tsaddik, describes the Maggid of Kozienice performing a daily bath. The Maggid was supposed to wash his head for the reason of aliyat neshama: During his mystical ascendances into heaven he had to cross rivers of fire, and afterwards used bathing to cool off the heated soul.

By the end of the booklet, a reader comes upon a section entitled Zayne Tayere Verter (His Dear Words). It constitutes a small collection of Guterman’s sayings and teachings based upon quotations taken from the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud and Rashi. This part of the booklet resembles traditional Ashkenazi kashes (kashiyot), difficult exegetic problems, usually burdened with (at least apparent) illogicalities. They were used in the course of polemical challenges (pilpulim), and frequently so during Toyre zogn, a tsaddik’s lecture given by the Sabbath meal. One of the lectures focuses on the story of Bilaam, who, guided by God, did not curse the people of Israel but blessed them instead (Numbers 23, 7-10). The tsaddik of Radzymin asks: Why has Bilaam suddenly turned into a good friend of the Jews, when he was none? To answer this question Guterman takes advantage of popular interpretations of Lurianic Kabbalah. Blessed by a wicked man, the people of Israel would derive their happiness from kelipot, the unclean shells of sin. This act of spiritual diversion was unsuccessful only because the Chosen People had already been blessed by God himself.

After a few paragraphs, however, the theme changes, again without any formal indication. The final excerpt mentions another instance of evidence of the prophetic talents of the tsaddik of Radzymin: When asked by a Hasid if there was any hope for a dying cantor, Guterman answered in the negative. Inquired later by his son, Yehoshua Shloyme, he tells a story about a vision he had during a daytime nap. The episode finishes without any additional formulas, as does the whole booklet. Instead of benedictions, which one may expect to find at the end of a Hasidic hagiography, Mayses Noyroim is closed only by a floristic ornament.

The stories are immersed in the reality of Congress Poland, especially its province of Masovia. The events take place in Radzymin and Warsaw, but references to other towns and villages of this region are quite frequent. Some surnames of local nobles seem to be intriguing material for further study as well. The Yiddish language used there is enriched with Polish words that do not appear in Jewish texts originating from lands without a Polish-speaking majority (kuratsye, napady, kovol, drozhkazh). They also bear some traces of local dialects. Moreover, very short quotations in Polish are recognizable and suggest that the author was somewhat familiar with the language.

***

The title Mayses Noyroim suggests that we are dealing with an emblematic hagiography that mirrors the ma’asiyot nora’im of Isaac Luria, the eponymous giant of the Lurianic Kabbalah, as well as some other Hasidic pocket books devoted to masters and leaders of the movement. To some extent this notion holds true, especially in relation to such characteristic motifs as Guterman’s modest background, spiritual lineage and the wonders that he performed. The tsaddik is able to be in two places at the same time and stay invisible, as it happened during the audience of a General Governor. He can see what happens in remote locations, for example at the home of the rabbi of Czyżew. The previously mentioned features of a typical Hasidic tale are generally present here, although sometimes more attention is accorded to secondary characters, whereas Guterman himself seems to control the events from behind the scenes.

Still at least the miraculous aspects of the booklet appear surprisingly rationalistic as far as the circumstances are concerned. Generally speaking, those are not naive accounts inspired more or less by older traditions, but rather testimonies of less direct engagement of the tsaddik. The effectiveness of his interventions is generally explained by the higher moral standards of the former generations. “Jews of that time were pious”—the author repeats several times, giving the reader an insight into the probable motives for publishing the book. This hagiography is not so much about Guterman (although it contains scattered information about his individual ways and customs) as about simple people, the “everyday Jews,” who may earn the right to experience wonders—just as their fathers and forefathers did—if they return to the path of piety. The Hassidic way of Pshiskhe, emphasizing the ethical virtues of a charismatic figure, is expressed even there, where working wonders seemed to prevail.

***

This article first appeared in Polish in Studia Historiae Scientiarum 16:4 (2017). It is reprinted in English with permission of the author. You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Marek Tuszewicki teaches at Poland’s Jagiellonian University’s Instytut Judaistyki.