A Is for Abish

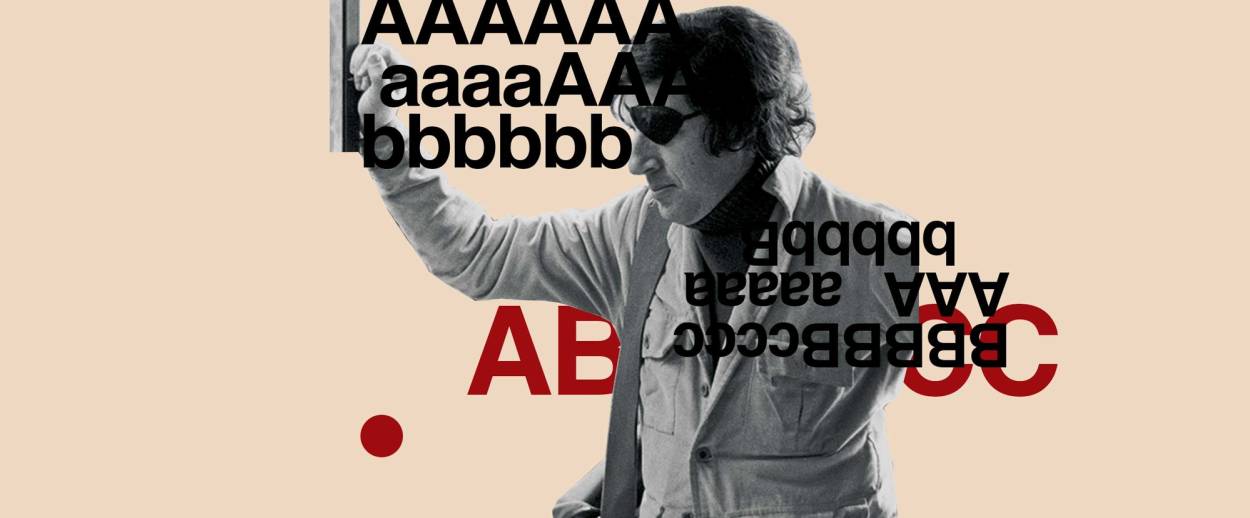

An Austrian-born American abstract artist arrives at 87 annī and amazes anew

Imagine readying yourself for a game of tennis—only to realize that the person on the other side of the net will be using the court to play a completely different game, one that seems to resemble pinball. That is what it felt like to sit down for an interview with Walter Abish, a Viennese-born American experimental writer and thinker. As we chatted at the Bowery Bar, Abish, who turns 87 today, did not dodge my questions: He slowly repeated them, smirking—and then proceeded to address these questions in a way that resembled an avant-garde performance, rather than an interview. “I’ll come to it later, if you remind me, because there’re too many diversions,” he half promised at one point. Between all of the diversions, free associations, and ironic allusions, I felt like I was dropped inside some warped and remixed theatrics of a page of Talmud.

In the 1980s Abish received the prestigious PEN/Faulkner award for his novel How German Is It, as well as a MacArthur Fellowship, aka a Genius Grant. Though experimental and cerebral, Abish’s later work received a fair share of mainstream attention. The occasion of our meeting, however, was the reissue of Abish’s very first novel, Alphabetical Africa, originally published in 1974 by New Directions.

Alphabetical Africa may be one of the strangest books you’ll ever encounter: Its first chapter is made up entirely of words that start with letter A. The second chapter has words that start with A and B, and so forth, all through the alphabet, until Z, at which point, things turn backwards. There’s a chapter with words starting with any letter other than Z, and so forth, all the way back up to the final chapter of A words only. The book is funny and surreal, erotic and erratic. Above all, it is surprisingly coherent, as it describes a trio of protagonists that traverse the African continent in a series of wild misadventures. Here’s the opening of chapter E: “Alva accidentally encounters an Ethiopian engineer bearing dandelions, but decides engineer’s action entails an enormous and energetic eagerness at both elbows. Ethiopian engineer cries, don’t, as Alva, eluding elongated Ethiopian arms, escapes. … Emitting English entreaties engineer collides against closing elevator door, almost admitting defeat, engineer considers all angles, all apertures, all doors, and deduces correctly another beginning and another end.” There is plenty of slapstick and amazing verbal dexterity here, but what’s more, there is also a sense that the book’s unfolding is not driven by regular plot considerations, but something larger and stranger—something that, though vaguely familiar, is outside of the realm of cause and effect.

Indeed, the same can be said of the unpredictable characters, as well as the narrator who, in the I chapter gloomily admits: “Inventors drift into inventing almost dreamily, almost by accident. For example, I came here, dreading heat, dreading ants, dreading bush fires, and being hit by a hurtling elephant. After arriving I immediately built a few defenses, I avoid enticements, I avoid African ceremonies, and I avoid being challenged by a gun-carrying hunter.” The narrator elegantly hints at the fact that the novel’s writing resembles dream-like free association and randomness. At the same time, he quite literally admits to his remarkable obsession with ants (there’s an army of them showing up, occasionally), as well as his programmatic avoidance of ceremonies and rituals, and the willingness to inflict severe physical damage on his main characters—Alex, Allen, and Alva.

When I asked Abish about these characters, he responded: “they’re … alphabetical beings … simply imaginary creatures. I have no idea who they are. But I also have no idea who the narrator is. To some extent he embodies me, of course. … I did circumnavigate Africa as a 17-year-old. I grew up in Shanghai under Japanese occupation. We circumnavigated Africa on the way to Israel because Suez Canal was not available.”

Having read Abish’s memoir, Double Vision, I knew that escaping the Shoah, Abish’s family moved to Shanghai, and later came to Israel. What exactly does that journey, however, have to do with Alphabetical Africa, the book’s characters, or the unknowable narrator, who resembles Abish himself? As I listened from across the table, it occurred to me that the connection was undeniably there, but it would be trite to reduce it to a biographical or, worse yet, psychological explanation. One thing is for certain: the word circumnavigation is extremely apt, if you are trying to describe the novel’s relationship with conventional literature, and even logic as such.

Is it possible to circumnavigate logic and remain coherent? Abish’s response: “I wasn’t looking to make sense. Sense is not important. Of course, today, the knowledge that galaxies have as many as 1 billion stars, possibly 2, it’s wonderful. It’s wonderful. You want religion? There it is. Hence, a different picture. And everything will collapse, will end. … I don’t have much hope for common sense.”

That stance against so-called common sense is at the core of Abish’s most renowned work, How German Is It. Seemingly far less experimental, the book tells the story of two German brothers, renowned architect Helmuth and widely read writer Ulrich. For much of the novel, the brothers reside in the upscale town of Braumholdstein, which at one point was known as Durst, the site of a concentration camp. The town is named after a fictional German philosopher, Brumhold—a thinly veiled version of Martin Heidegger—and is most orderly, civil, friendly, and progressive. One day, the sidewalk falls through to reveal a faulty sewer system, and with it, a mass grave, right underneath the town’s beloved bakery, whose pastries are described with gusto. And that is the book’s key metaphor: The novel as a whole presents a post-Holocaust German society, orderly and comfortable, and which, at any point could implode to reveal the literal and philosophical mass grave underneath. The book’s title, then, is a reference to philosophy, literature, and the rich German culture invoked at every turn by the book’s protagonists—but it also offers a far more difficult and accusatory question: How German was the Shoah itself? Could it be that it was not the madness, but rather the orderliness, efficiency, and logic, coupled with the deep national pride that made the Shoah what it was? None of this is explicitly stated but at every turn, the accusation hangs heavily in the backdrop.

Of course, Abish is not the first to question whether “common sense” is, indeed, sensible, and “logic,” humane. Even prior to the Holocaust, reacting to the atrocities of WWI, Dadaists and Surrealists already sought to wipe the slate clean, and create a new kind of literature, disentangled from “realism.” Within the decade prior to Alphabetical Africa, Georges Perec—another European-born writer who survived the Shoah as a child—attempted to investigate our notions of logic by creating his own literature of constraints. Perec’s novel Les revenentes (1972) is a work in which the letter E is the only vowel used throughout.

There is a correspondence between the works by Abish and Perec and medieval kabbalistic writings, which describe the innate power of the alphabet, and the sacredness of the letters’ placement, arrangement, and relationship one with the other. In kabbalistic mythology, the letters exist not only in the service of comprising words. They also contain their own decontextualized significance, and offer an alternative way of seeing and contemplating the world.

Is it surprising that Kabbalah, a medieval product of Jewish exile, sought to recreate an alternative logic system, just as various 20th-century writers, many of them Jewish, proposed that the world’s destructive tendencies can only be eradicated with the critical approach to thinking as such?

Is it possible to rethink thinking—and not just the content of it, but the methodology, as well? Does Alphabetical Africa offer a viable model? “I’m still waiting to discover if there’s any meaning to it. The idea of creating something I don’t understand very well is quite satisfying,” answered Abish, beaming.

When Alphabetical Africa first came out, esteemed poet and translator Richard Howard, reviewing the book for The New York Times, suggested that it ought “not to be paraphrased or summarized, merely experienced,” which, Howard went on, is the “definition of a poem, and of certain psychotic states.” Abish, recalling Howard’s writing as we spoke, called the review “very strange.” I think he meant that as a compliment.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).