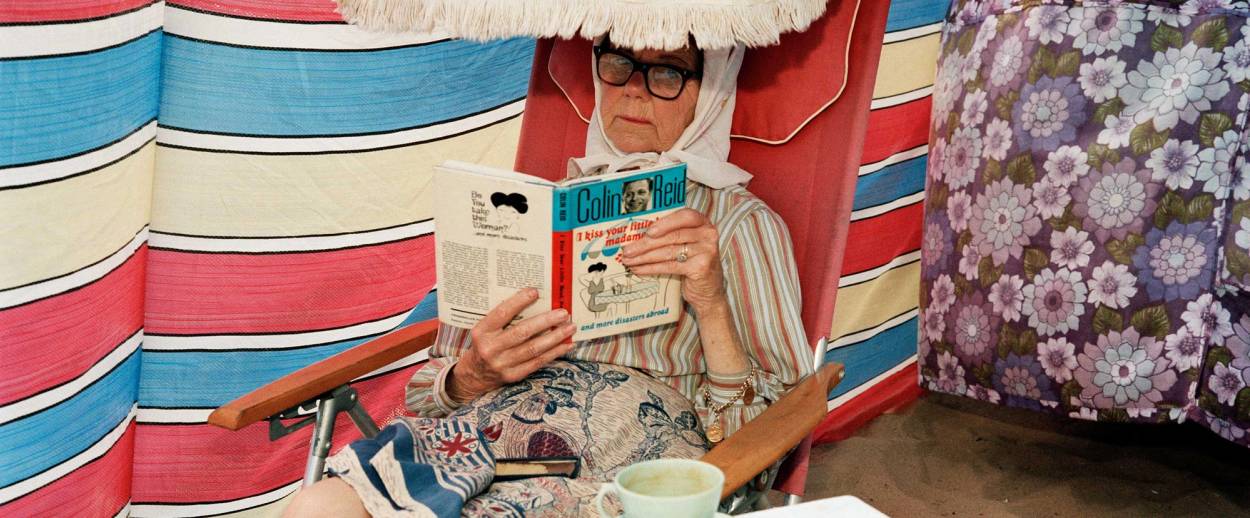

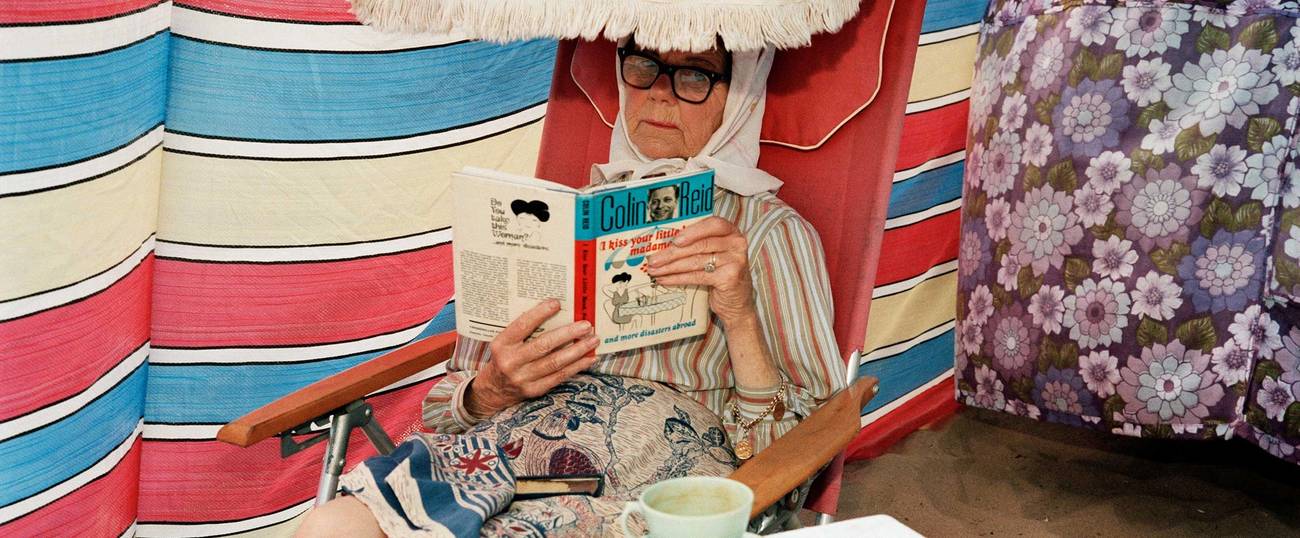

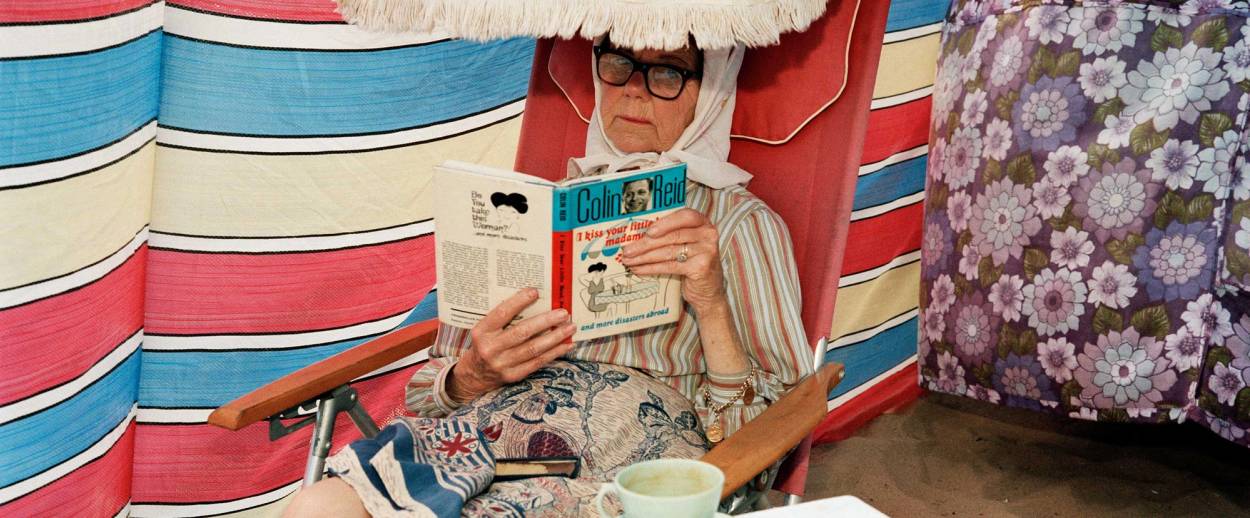

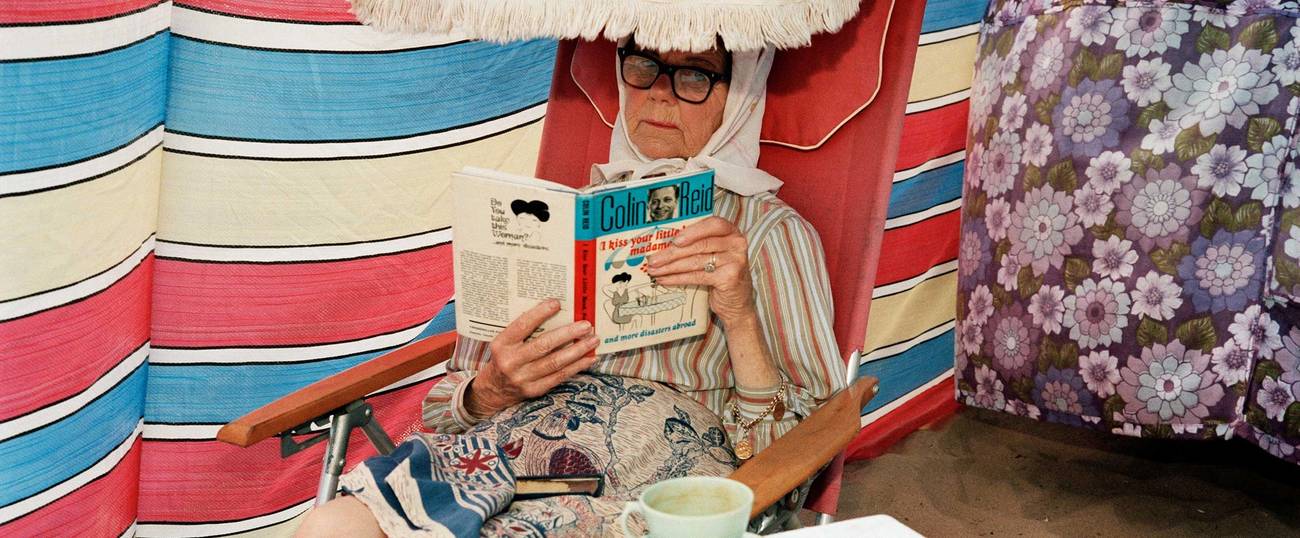

The English Jew Who Read My Book

Or, how the Jews reconquered London

From his fidgetiness I took him to be one of those embryonic, not-quite characters—not quite a barrister, not quite a doctor. A law clerk maybe, or a pharmacist. Not quite married. We were by the pool of the King Solomon’s Palace Hotel in Eilat, he the only man among a group of women doing a morning keep-fit class, I sitting under an umbrella reading, resting up during my first visit to Israel. I needed a break from Jews asking why this was my first visit to Israel. The minute he saw me he made a scribbling motion with the hand that wasn’t holding up his shorts. The gesture reminded me of the way my father used to call for the bill at the end of a meal. Mene mene tekel upharsin he might have been inscribing on the restaurant ceiling, so magnificent in its portentousness was the movement of his finger.

The pharmacist—as I’d now decided he was—fared no better getting my attention than my father had getting the waiter’s. People don’t like to be scribbled at. What was I expected to do? Make like I was writing back? Eventually, he quit the class and came across. Over his nebech shorts he was wearing a T-shirt advertising what must have been his own brand of energy pill. “Remind me what your book’s called,” he said, “I may have read it.” “You won’t have,” I assured him.

A day later I saw him going round the hotel asking people to punch him in the stomach. Harder! Harder! That was how strong his pills had made him. He didn’t invite me to have a go but reprised his frenzied air-scratching whenever he saw me, on one occasion saying “Still writing?” and shaking his head in pity.

The following week at a demonstration against something or other in Jerusalem I was accosted by a young Hasidic Jew of the sort who is always in a hurry, his shirt tails out of his trousers, his fringes flying, his shoelaces undone. Though there was no wind, he held on tightly to his homburg as he rushed over to me. He was from Liverpool. An accountant. He knew what I did. A question he had long been wanting to ask me—“Why?” “Why what?” “Why do you write books?”

I took him to mean, “Why did I write books when I could have made a better living in accountancy.” I began from the beginning—that usually shuts them up—telling him how I’d always wanted to be a writer, how, like Pope, “I lisped in numbers for the numbers came,” but the mention of a Pope scared him. I had entirely misunderstood him anyway. He didn’t want to know what had made me a writer. His question was about God and the Logos. He wanted to know why I wrote books when We already had a Book.

It would be no exaggeration to say that these two random, self-selecting representatives of Anglo-Jewishness—one a holy accountant from Liverpool, the other a secular tsedraiter from Bushey in North London—define the philistinism that has bemused observers of English Jews for centuries. Either we are a people without a book altogether, or we are a people with only One.

Forced to choose, my instinct has been to throw in my lot with the holy on the grounds that one book is better than none. Someone said that all novels are essentially commentaries on the Torah. As a novelist with a penchant for hermeneutics, I am not unwilling to entertain that thought. D.H. Lawrence said he wrote out of a religious sense, and he wasn’t even Jewish. But religion lets you down in the end. Once, a rabbi invited me to Shabbes dinner, promising that the spirituality of the service, as presided over by him, would convert me to orthodoxy. All went fine as far as the candles and the prayers were concerned. Shabbes has lovely moments. Havdalah is both beautiful and profound. God who divided this from that, thereby teaching us the virtues of discrimination, deserves all the praise we bestow on Him. Face to face with Yahweh, Jews remember to be serious. The pity of it is that they forget again the moment He departs.

The solemn rabbi of 30 minutes before, his skin still luminescent from his encounter with the Divine, began to enthuse about the stage version of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang to which he’d taken his whole family three times. His wife, who’d filled the room with serenity in the act of kindling light, moved the conversation on to the trouble she was having getting a flight to Disneyland in Florida. No wonder God retires so promptly from the company of people for whom he once nursed grand ambitions. I scanned the bookshelves as I left. No Babel or Bellow, no Roth (Joseph or Philip), not even Sholem Aleichem or Isaac Bashevis Singer. Just rows of scripture commentaries in bad-taste bindings and a single paperback novel by Wilbur Smith. I’m the real Jew, I thought, as I took my coat.

Roth (Philip) liked running down English Jewry for its cultural parochialism. Maybe it made him feel better about Newark, New Jersey. English Jews of the more than One Book variety have been equally censorious, but more understanding. It stands to reason, after all, why we are who we are. Camouflage. Fearing conspicuousness, Jews take on the intellectual coloration of those among whom they think it wise to conceal themselves. Put a Jew in the same room as Bach for long enough and he’ll come out composing cantatas for Christmas. Ease him discreetly into English society and it should be no surprise he’ll end up ill-read, sporting a double-barreled name and wanting to ride a horse. (To which list we can now add voting Brexit.)

A young Hasidic Jew wanted to know why I wrote books when We already had a Book.

So it’s with no small degree of satisfaction that Anglo-Jewry cocks a snook at its critics when London Jewish Book Week comes around at the end of February and sells out of tickets the minute it puts them on sale. It’s accepted wisdom that you can’t get an audience in London for anything literary. Outside the capital it’s a different story. There is no corner of an English field, however remote or muddy, that doesn’t accommodate a writers’ tent once a year. But London, that has seen everything, is harder to impress. Even the bookshops struggle to put on a book event.

Then along comes Jewish Book Week (not just any book week but a Jewish book week) attracting the most demanding audiences—not all of them Jewish by any means—for the best contemporary essayists, biographers, philosophers, scientists, historians, poets, novelists—not all of them Jewish either. And you fight to get a seat. That’s not hyperbole. It’s a week of sell-out talks and if you haven’t got a ticket you ring up everyone you know to see who they know who can get you one. I was contacted once by a well-known oncologist who was desperate to see David Grossman. The implication was clear: I might be in good health now but a time might come when I’d need his help, and he had a long memory.

I’m not old enough to have gone to its first events in the early 1950s. I imagine them to have been diffident and sedate. They weren’t much bolder when I started going in the 1980s. Asked to choose their favorite Jewish book ever, an audience overwhelmingly went for The Diary of Anne Frank. Asked to choose their second they picked the Diary of Anne Frank’s sister, and so on through the whole family. So what about living Jews? No interest? Yes, yes, of course. But were such books being written?

Well if they weren’t then, they are now. What James Joyce discovered a hundred years ago—that if you really want a hero for all time, he has to be a Jew—is enjoying renewed momentum. Readers who come to Jewish Book Week haven’t given up on Anne Frank, but in our troubled, not to say apocalyptic times, the experience of contemporary Jewry, life as lived by Jews or affected by Jews, life in the face of Jews, life as it wouldn’t be but for Jews, life as told in Jewish stories, life that only the Jewish spirit of bleak play can reach, life that is particularly Jewish by virtue of having no Jew in it, matters to them just as much or more.

Jewish Book Week is not a revelation to English Jews; it’s a reminder. The volcano might not have been erupting but it never was extinct. Jews have long abounded, for example, in British publishing. They just weren’t that interested in publishing what was Jewish. That haughty self-disdain has passed. To be cultured is no longer to be someone else.

At a signing at last year’s Jewish Book Week I came face to face with a tsedrait expression I’d hoped never to see again. Its owner extended a hand and laughed. “Remember me? King Solomon’s Palace?” “No,” I answered. “Never been there.” “I’ve finally read it,” he said. “Finally read what?” “Your book.” I could have let him off, but I didn’t. “Which book?” He seemed astonished to discover there could be more than one. But consider: Something had got him out of his pharmacy in the wilds of Hertfordshire and into a book festival in central London. Deep below the surface of things, in the germinating dark, the English Jews are stirring.

We could choose to be cheered by that, or we could remember that Jews are civilization’s weather vane, and bad stuff is on the way.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Howard Jacobson is a novelist and critic in London. He is the author of, among other titles, J (shortlisted for the 2014 Booker Prize), Shylock Is My Name, Pussy, Live a Little, and The Finkler Question, which won the 2010 Man Booker Prize.