Confessions of a Post-Colonial Jew

‘The Judaism I found in America and here in Israel is a failed reconstruction of the organic Judaism my grandparents knew as children’

Like most people in the First World, I live at many removes from the world in which my grandparents were born: Lithuania in the 1870s. I was born in 1944 in the United States. My parents and I were English-speaking Jews in a prosperous, democratic, tolerant society. My grandparents and their parents were Yiddish-speaking Jews in an autocratic, hostile empire. I imagine that the provincial towns and villages where they were born were like some cities today: full of mud and garbage, dark, insalubrious, and dangerous.

My grandparents, until they emigrated to the United States, were entirely Jewish in culture, language, and ethnic identity. They remained deeply and conspicuously different from the non-Jews around them. I was (and partially remain, though I have lived in Israel for more than 40 years) deeply American in culture and language, not outwardly different from other Americans in any immediately recognizable way, but Jewish in ethnic identity. My parents and I assimilated without repudiating Judaism, whereas my grandparents could only have assimilated into the dominant Russian culture by converting to Christianity. Our assimilation was quite easy, and I never thought very much about what we lost by it until I was a young adult, which was when I decided to live in Israel.

My grandparents weren’t explicitly offered a Faustian bargain when they moved to the United States. No one said to them, “Give up your Jewishness, and you can reap all the benefits of American openness and progress.” In fact, they never did give up their Jewishness. They spoke with Yiddish accents until the end of their lives, though they came to know English well. My parents, their siblings, and the third generation of our family all grew up as Americans in a society that by and large accepted them. Yet I felt that my American identity was an ill-fitting garment.

Although we Jews like to think of ourselves as unique, our displacement is part of an enormous historical process that continues to affect hundreds of millions of people. The leap into modernity from traditional societies has been a universal cause of anguish and confusion in the past two centuries or so. Rural populations became urban industrial workers in their own countries. Many others left Italy, the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, Ireland, China, and other poorer lands and migrated to the United States and other places where they could make a better living and escape oppression—frequently winding up as wage slaves in sweatshops and noisy, dangerous factories. In Asia and Africa, European colonial regimes created and trained local elites, removing them from their traditional societies, teaching them new languages, and expecting them to behave like Europeans, while looking down on them for not being European. All of us, the descendants of these displaced people, lost a major part of our connection to our ancestors’ past.

***

Like countless viewers all over the world, I watched The Sopranos with pleasure and curiosity. I grew up in Greenwich Village, in Manhattan, bordering on Little Italy. When I was a boy, my parents took me to small, family-owned Italian restaurants. My mother bought almond biscotti from Italian bakeries, and, as I walked down MacDougal Street to my school on Bleecker Street, I passed Italian grocery stores and other small businesses with Italian family names in gold letters on the plate-glass storefronts. There was an Italian funeral parlor across the street from my school. Every year there was a street fair for Saint Anthony of Padua. When I saw Cinema Paradiso, the people’s faces looked just like the people I used to see around me as a child. Not only that, lots of my relatives live in suburban New Jersey, Tony Soprano’s stomping ground.

To acquire Jewish culture, the culture of my grandparents, I had to make it up.

I was fascinated by the characters in The Sopranos, because they are Italian in almost exactly the way that American Jewish people of the parallel generation—my generation—are Jewish. They have the food, the religion (which they don’t necessarily take very seriously), and the family connections, but they have lost the language and the culture in which their grandparents were rooted. Like other assimilated ethnic groups, in return for trading in their family’s traditional culture, Italian Americans gained the chance to excel in America, not—despite the stereotype—as criminals, but as doctors, lawyers, engineers, business people, politicians, entertainment professionals (like David Chase, the main writer of the series, and the excellent actors), and as academics. Nevertheless, as The Sopranos makes clear by sending Tony to Italy, by having him fantasize about an Italian girl, and by bringing an Italian mafioso to New Jersey, these people are not entirely comfortable in America. (Perhaps, as the 2016 presidential election results show, nobody is truly comfortable there.)

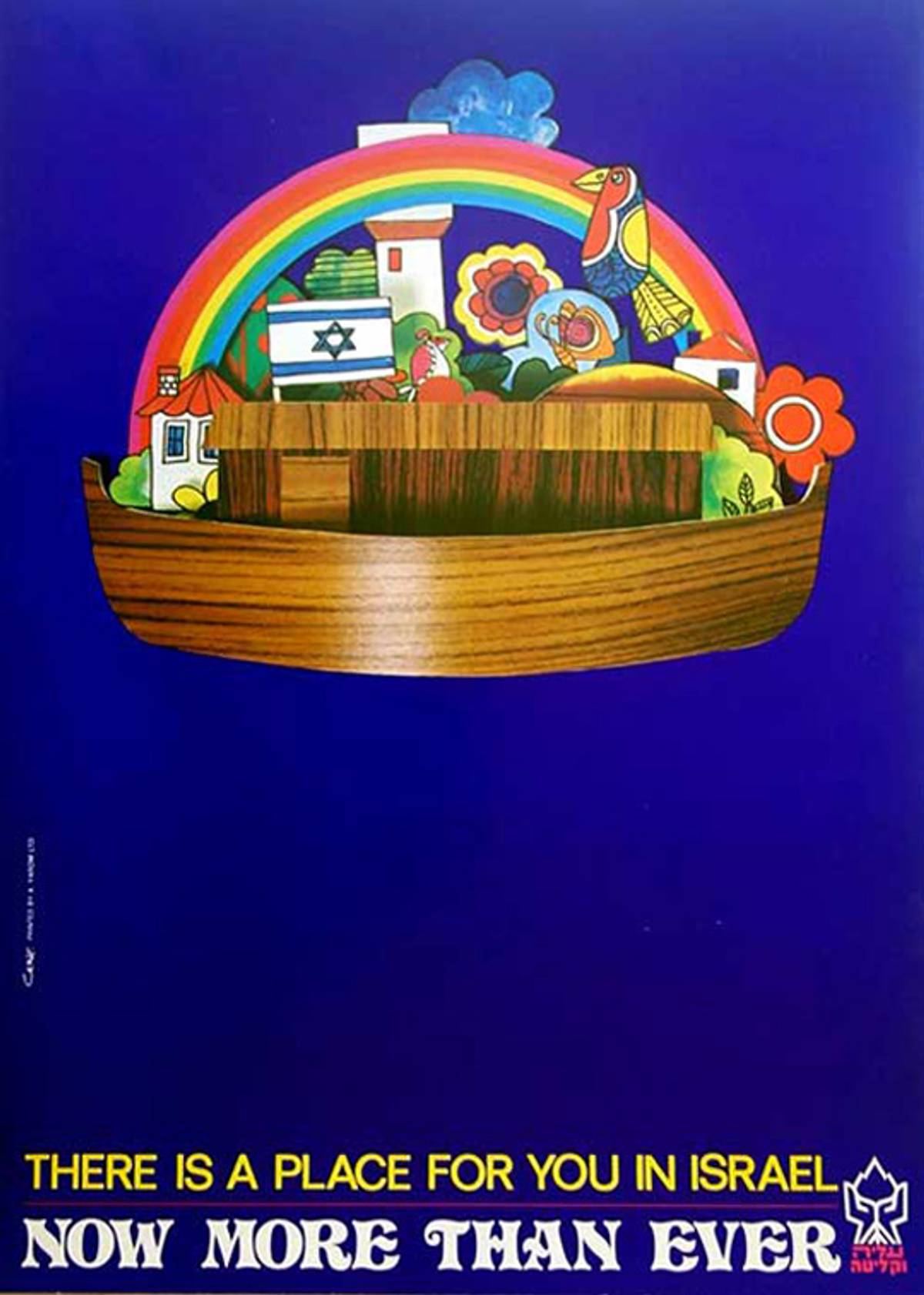

My decision to move to Israel was an effort to alleviate this discomfort and restore my connection with the Jewish past. As I should have known, this effort was doomed to frustration and failure. Israel itself was founded on rejection of the Jewish past and the aspiration to produce a new kind of Jew, and, of course, the Holocaust had obliterated what was left of traditional Jewish society in Europe. I couldn’t go back to Vilna to learn Yiddish, but I learned something very important about the immigrant experience undergone by my grandparents by reiterating it, although far more comfortably.

An immigrant generation is a confused generation. Understanding a new and foreign society is daunting. My grandparents arrived in the United States with no financial resources to speak of, without knowing English, without a modern education, and in an environment where people were expected to fend for themselves. Like millions of other immigrants who arrived in America at that time, they had no knowledge of American culture and society, few tools to understand their new environment, and no letup in the constant pressure to make a living, so they could never step back and figure things out.

Not only were they disoriented, with no useful conventional wisdom to guide them in their new country, they also were unable to explain how things worked to their children. So, the children had to figure out their environment on their own and lead their parents into American society. For example, my wife’s late aunt, who was born and raised in Chelsea, Massachusetts, once spoke to me about the flood of 1909, when she was a schoolgirl. She and her sisters had to be the family spokespeople when they went looking for shelter in homes on high ground because their parents didn’t know English. Similarly, though less dramatically, when our children were in elementary school in Israel, my wife and I often had to ask them to translate notes from their teachers for us.

Being a well-educated, affluent, English-speaking immigrant in Israel is much easier than being an indigent Yiddish speaker in America with no relevant formal education. But I can’t exactly say that I’ve assimilated into Israeli society, even after my four decades of residence here, military service, and acquisition of the Hebrew language—which I still speak with an accent. Moreover, I’m not sure that my nonassimilated Israeli-American-Jewish identity suits me any better than the assimilated American identity that I discarded.

Because I am so comfortable, I’m uncomfortable making the claim that I’m dispossessed in any way—though I am (and you are, too, probably). My parents sent me to an excellent private school in New York. I attended Ivy League universities. My family’s wealth, though moderate, was sufficient to provide me with enough financial security that I didn’t make any sacrifice when I chose a far from lucrative profession. I’m not complaining, just observing. And what I’m observing is that, to acquire Jewish culture, the culture of my grandparents, I had to make it up—not by myself, but with the help of friends whose homes had been less removed from their Jewish origins. I learned Hebrew and studied and practiced Judaism. However, the Judaism I found in America and here in Israel is a failed reconstruction of the organic Judaism my grandparents knew as children. I wouldn’t go back to that oppressive and oppressed culture for a minute.

Traditional cultures do not equip people to live in the modern, let alone the postmodern world. To participate in the advanced economy, people have to become what their ancestors weren’t. My father’s father was a dapper, handsome, outgoing man, and, as my father put it, “He was a joiner.” He was a member of the Masons, the Elks, the Moose—whoever would accept him. He came from Czarist Russia, where the only gentile organization that would take him gladly was the army (which is probably why he fled to America). Acceptance by American society, as incomplete as it was, parodied by Groucho Marx as Rufus T. Firefly and his other grotesque and cheeky entrepreneurs, was vastly empowering for him.

I am not a foreigner in the modern world. My loss was inevitable.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Jeffrey M. Green is the translator of more than a dozen books by Aharon Appelfeld. He is the author ofThinking Through Translation, and the novelSite Report.