“This country committed a crime against me,” said Iraqi-Israeli novelist Samir Naqqash (1938-2004) in Forget Baghdad, a 2002 documentary on Iraqi Jews. He meant Israel, not Iraq: not the country that had expelled him for being a Jew, but the country that had given him refuge as one.

Naqqash made aliyah at age 13 in 1951, during the final phase of the mass exodus of Iraqi Jews that began in 1949, and included airlifts that began 69 years ago this weekend. He moved from a materially comfortable life to one of hardship: The Iraqi government confiscated the wealth and assets of expelled Jews, including those of Naqqash’s family, who ended up in the ma’abarot (transit camps) set up to house the sudden influx of his and other Mizrahi Jewish communities. His lifelong negation of Israel began immediately, and only deepened in complicated ways over the course of his life.

Naqqash took long, ultimately unsatisfying trips to other nations peripherally linked to his Iraqi Jewish ancestry: India and Iran. After his father died, two years after he arrived in Israel, Naqqash and his brother undertook a botched attempt to flee to Lebanon in order to reach Britain, one of several attempts to awake from the nightmare of history, including an attempt to acquire “international citizenship.” But he remained an Israeli, and wrote five story collections, four novels, and three plays.

Devising a writer more at odds with his circumstances would be difficult. Naqqash was at the Jewish margin of the Arab novel and the Arab margin of the Israeli novel. He wrote exclusively in Arabic—including the Iraqi Jewish and other Iraqi dialects—and was so averse to the prospect of writing in Hebrew that he threatened to sue Shmuel Moreh, his professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for suggesting he write his master’s thesis in that language. Most of his potential Arabic-language audience outside of Israel lived in countries that did not recognize the Jewish state, and in which communication with Israelis was illegal. This left Naqqash to imagine his own private tragedy within the largely unspoken communal tragedy of Iraqi Jews.

A Jew transplanted from one ancient home to another, and scantly read in either, Naqqash has mainly existed as an academic curio, in a parallel purgatory to his personal one. The recent publication of an English translation by Sadok Masliyah of Tenants and Cobwebs—Naqqash’s first novel, originally published in Arabic in Israel in 1984, and his first translated into English—is set to mark a significant moment in the life of his work. If Israel is the Jew of nations, and Israelis are the Jews of Jews, then Naqqash was a Jew among both.

Naqqash was part of a special generation of Iraqi Jews: the last to have direct experience of the country, and the first to be able to write and speak freely about their experiences, from Israel and diaspora. “I was a spoilt brat,” Naqqash said of his childhood in Iraq. “The entire family was involved in taking care of me.” It was a materially comfortable life, but also one replete with a bounty of experience: sensory, verbal, social. “Our house was a kind of meeting place for many different kinds of women and men,” Naqqash said. The presence of Christian and Muslims (including “Muslim women of all classes”) was common. The opportunity to listen to those other voices from within it, were taken from him through upheaval.

Forget Baghdad documents the upheaval that generation experienced through its authors, including Naqqash, Sami Michael, and Shimon Ballas. The relief at seeing these writers able to express themselves openly is offset by the complex pain of their testimony. But as they recount their trajectories, there is a gradual, if always tormented, reconciliation with Israeli life. Shimon Ballas has a nocturnal vision in which Arabic letters and poems assail him in revenge for his decision to switch to Hebrew, but he persists. Sami Michael, who longs for “wide, open” Iraq, says that in stifling Israel, “everything is artificial, in aid of a certain ideology.” But he has a daughter, and the realization that Israel is her home forces him to attenuate his own sense of alienation.

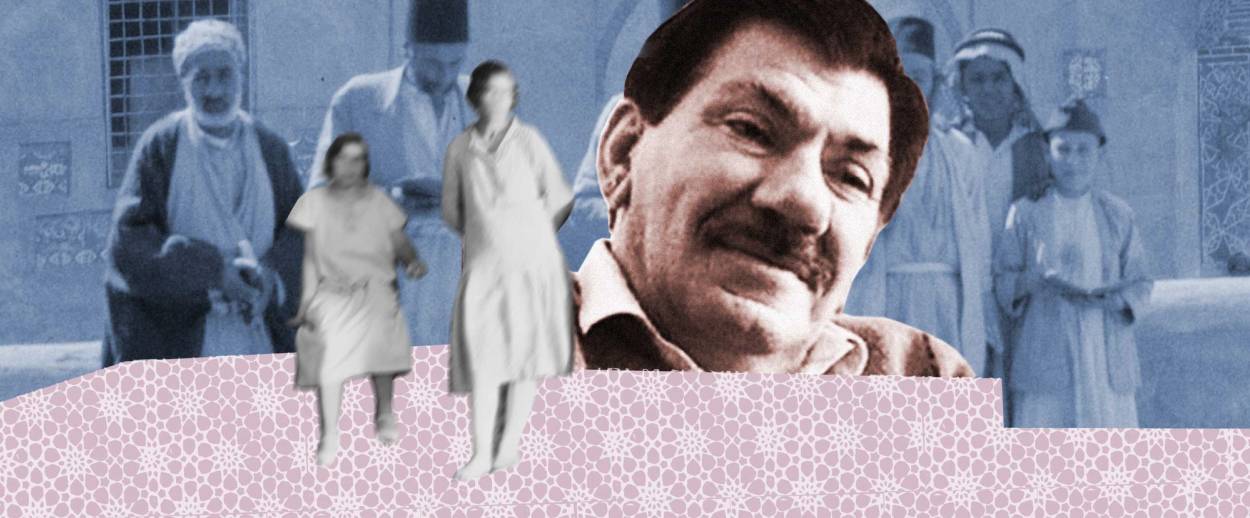

Naqqash, however, conveys a starkly contrasting temperament. Childhood photos show a relaxed, stimulated boy. But a year before his death, Naqqash speaks at an angle, his head poised between uprightness and his own shoulder. There is exhaustion, defeat—but underneath, a desire to be understood in all his profound self-pity. Over time, his soft eyes receded further into his exquisitely melancholic face, as if into the past.

“We passed the Tigris,” Naqqash recounts of his final moments in Iraq, “and I remember how I feasted my eyes on the sight of the river. The lights of the street lamps were reflected in the water. This farewell image of Baghdad is alive and embedded in my memory to this day. Even though I was young, it is deep inside my heart. All this love will never leave me.”

Several years in the transit camps, replete with poverty and miserable hygiene, and the perception of ingratitude by Ashkenazim, represented in David Ben-Gurion’s remark that they “kicked out good Arabs and brought in bad Jews,” made it clear that the travails of Mizrahi Jews did not integrate straightforwardly with the historical experiences of European Jews or the struggles of pre-independence Israel. The particular intensities of S. Yizhar’s seminal 1949 novel Khirbet Khizeh—the exhilarated shock of the European Jew holding a gun on his land instead of having one pointed at him—were external to the Iraqi Jewish experience. While Israel was fighting for its independence, Iraqi Jews were feeling the brunt of Iraq’s own consolidating sovereignty.

Iraqi Jews were, in that sense, external to the formative experiences detailed in Khirbet Khizeh, which established an existential frame for Israel, defined by conflict with Palestinians and its moral and political legacy. Yizhar’s vision of Israel on the cusp of independence—when “the entire world folded and became a single demand, a single desire, a single belief, blinding like a great light”—indeed had global significance. But the sense of centrality embodied in it applied differently to the Mizrahi Jews on its periphery: Zion had once more become the center of Jewish life, but it was a center that removed them from their own lives.

Naqqash became known more as a flattened symbol of anti-Zionism than an actual writer. Scholar Ammiel Alcalaay, in the introduction to a textured interview with Naqqash in the first anthology of Mizrahi Israeli writing, describes a “life and oeuvre [which] attest to a steadfast act of resistance towards the massive socialization process undergone in Israel by Jews from the Arab world.” But his decision to continue writing in Arabic was most profoundly neither an act of solidarity with Arabs nor resistance to Israel. As the author himself put it: “A Jew who writes in Arabic presents all kinds of problems to everyone, yet I am simply continuing to write in my own language. … I think that someone who professes to change from one language to another loses all direction. … Naturally, I prefer the language that I can express myself best in.”

For Naqqash, using the Iraqi dialects in particular was not about “setting down dialects that were in the process of being forgotten,” but about being “more faithful, more representative of reality.” Arabic was the only language that Naqqash was intimate enough with to give any kind of life to universal ideas and images; writing in it was his only chance to immerse himself fully enough in the only world he knew well enough to transcend.

“I am against ‘committed’ writing, partisan writing that takes as its goal a certain problem, or a certain theme,” Naqqash said. “Jews, in general, write about the ‘Jewish’ problem. This also occurs in Palestinian writing, where many writers focus themselves only on the Palestinian ‘problem.’ I believe that literature must be universal or, more precisely, individual.”

Naqqash locates himself in the Jewish literary tradition most resonantly, not in his connection to communal suffering or private knowledge, but in the channeling of his alienated sensibility as a way to break through to the universal. “Tantal,” a story that the writer originally published in the 1978 collection Me, Them and Schizophrenia, is told in three parts: one set during a Baghdad childhood and two in Israel, just after aliyah in the 1950s and then in the early ’70s. In Baghdad, the unnamed protagonist lives in “a mansion on the edge of a wilderness,” in a recently developed neighborhood. The child is drawn not to the amenities—the “in-built oil heaters and air conditioners” that had replaced the “bronze brazier” with its “aroma of dried orange peel”—but is rather magnetized by what is beyond the surface of change. He would take his grandmother by the hand from her room—a “living monument to the old”—to the porch, awaiting stories.

One day, she casually mentions Tantal—a jinn-type creature of Iraqi folklore. “Tantal likes to fool around with people,” she says. “He does not hurt really, he just likes practical jokes.”

Tantal immediately fascinates the child. He doesn’t know exactly what it is or when he will see it, and how he will recognize it if he does, but is convinced that it is “not a myth but a reality that the entire town perceived.” His uncle has even seen Tantal. While he was guarding an “endless” fruit orchard with a Muslim soldier, a bulletproof palm-tree size man confronted them, leaving the uncle unable to leave his bed for three months. In the barracks, Tantal takes the form of an old Bedouin dwarf, begging the uncle for food, who tosses Tantal away after feeding it. A beautiful woman standing outside a mosque calls the uncle’s name as he strides past her. As he hesitates over whether to respond to her call, rocks begin to pelt him from behind. In a play on Orpheus, the window of possibility closes itself before the decision to look back is taken.

The uncle “became used to Tantal’s practical jokes and knew that their ordeal usually left only a passing memory.” “Dreams,” he would say, “dreams that you remember, and that’s all.” But the protagonist remains “possessed by burning images and illusions that blended reality and dream.”

He consults a mythological encyclopedia in an attempt to make sense of Tantal, but to no avail. “When no gratifying answer was there, I sought solace in the outside world. And in forgetfulness. The nastiest of all human afflictions—forgetfulness. But it helps us live.”

He arrives in Israel, where “tents [replaced] uprooted trees,” and sinks into the malaise of the camp, where “the urge to see Tantal, together with the fear and cowardice that came with it, started competing with each other.” Twenty years later, the protagonist returns to the site of the camp, now a “humble but horrific suburb,” whose “ugliness remained in the semblance of modernization.” He encounters his uncle, who is tired by his nephew’s ongoing refusal to accept Tantal given the lack of direct contact.

Walking along the Mediterranean in despair, utterly removed from the apparent reality around him and burdened with “thirty solid years” of “worthless memories”, the protagonist suddenly becomes gripped with the desire to touch Tantal: “our only certainty, everything else is an illusion.” He walks into the sea and begins to be carried by it, but starts to panic, a “moment where combating existence became real.” A giant hand pulls him toward “the limitless monster,” but the gap between them only seems to widen.

The protagonist asks the giant who he is, and receives laughter in response, before the giant disappears. Alone on the shore, “an inconsequential feather that the sea was toying with, but still capable of thinking and of remembering,” he shouts with all his strength that he has finally seen Tantal. The certainty of his vision is conveyed in the echo of his own words: “It’s Tantal.”

The constant struggle over the existence of Tantal—trapped in the internal rancor between belief and the desire to believe, and forgetfulness and the desire to forget—is deeply rooted in the experience of exile. The Iraqi diaspora is a noncontiguous parliament, in constant negotiation over cause and effect, seeking the root of their dispersal and the dimensions of what was lost.

Tantal is not representative or symbolic: It is something, a something that is and is not there. It is the impossibility of lasting contact with a moment. For Naqqash, history has no sense. And time is only linear in the diminished form in which it arrives to us as we try to force sense into it. Time and history open and then close forever, leaving the taunt and jest of memory in their wake.

Sasson Somekh, in his memoir Baghdad, Yesterday: The Making of an Arab Jew, posits of Naqqash’s story “The Night of Arabs” that Naqqash was reflecting “a past that even then had already begun to recede.” But what is missing in this claim is the understanding that to write is to confirm the disappearance of what you write about, to necessarily reflect what has already passed. The act of writing—whose resources are memory, and the manipulation of it—is the only way that Naqqash could unbound the universal from the accidental particulars of his exilic life.

Cobwebs and Tenants is set in Iraq during the tumultuous 1940s, and depicts the demise of the Jewish community in the face of Iraqi nationalism and concomitant anti-Semitism. There are some 30 protagonists—Jewish and Muslim—who mainly live in one Baghdad apartment block, and a destitute alley adjacent to it. The narration moves from one internal monologue to another, cutting across time and experience, both within a passage and across the course of the novel. The movement of action is toward ruination—the unthreading of Iraqi society and the end of the Jewish community.

But Naqqash is less interested in a linear historical narrative than in encompassing the total experience of Iraqi Jews in light of their decline. He does so through an immersion in the individual consciousness of suffering. The disintegration of the Iraqi Jewish community has a collective cause, but the effect is to create innumerable different sorrows that pass into the collective only through points of flow between them. Subtle harmonies or discordances between the internal monologues only assemble in the perceptions of the reader, who is free to draw links between the delimited perspectives of the protagonists that evade their mutual understanding.

Naqqash writes with intense and whirling vividness about what Joyce called the “ruin of all space”: the sensory components of reality, the stable sense of the body, and all phenomenological certainties are overturned, warping the very fabric of mental and social coherence. Pockets of space and time suddenly expand and contract. Expectation, memory, and perception collapse into one another.

The “spinning propeller” of nationalism means that the circle of Baghdad is “closing, becoming a ring.” Self-awareness is heightened through internal disorder, before the possibility of a Jew living as an individual Iraqi disappears.

Yet the Jews of Tenants do not respond to their collective persecution by rising together. They are bound mainly through terror and confusion. Zionism and communism plant themselves as political forces fundamentally beyond their comprehension and utility, disfiguring their sense not only of place but also of self. Believing the merchants of destiny behind political movements is depicted as an act of desperate ignorance. “Our government has sold you out,” says Mahdi, a Muslim character, of Jews. “I tell you, one person has sold you out and the other has bought you. You’re the goods.”

Within the social world of Iraqi Jews, this attempt to frame an incomprehensible uprooting as a kind of conspiracy had a banal aspect. In Forget Baghdad, every Iraqi Jew the filmmaker interviews is convinced, despite a lack of evidence, that Mossad agents were responsible for bomb attacks against Iraqi Jews in 1950-51. There is a palpable and saddening desire to establish a common understanding—a kind of floor of sense on which to build mutually reinforcing sympathy—in order to more stably process a shared experience of devastation.

Tenants provides a hideously vivid vision of the sweeping up of both victim and perpetrator by fascism, as a force greater than cultural discrimination, the volition of political actors or the sum of individual hatreds. What is most profound is not the unleashing of extraordinary hatred, but the failure of ordinary humans to rise to the level required to overturn a much greater force.

’Alwan, a Muslim character, embraces the circular viciousness of anti-Semitism: forcing Jews into separateness and then punishing them for it. Transformed by the “whore” of politics, he berates his childhood friend, the Jew Ya’qub: “Didn’t I say you were all traitors and bastards? Do you see now how right I was? All of them are leaving the country. They appreciated nothing. Now you leave! Go fly with them, fool, one way with no return!”

“But I am a Jew, ’Alwan, my friend for life,” thinks Ya’qub to himself. “I pretended not to see what you did in the Farhûd [June 1941 pogroms against Baghdadi Jews]. I did not move a muscle against you. In general, it’s better to distinguish among things and not mix them up, but you’re no good in making distinctions.”

Naqqash’s play on distinctions and opposites in Tenants is highly skillful. Here, distinction based on value is presented as a way out of the malevolent and false distinctions of fascism: a notion derived from being on the receiving end of its opposite effect.

“No, ’Alwan!,” Ya’qub says to himself. “I may be a Jew, but I’m not a traitor. How could I betray a homeland containing soil holding the remains of my father and forefathers? This land is made of us, ’Alwan. We lived in it before you were born. When you were sperm, we had already completed compiling our Talmud, our Jewish law. I was here in this land before you, twelve centuries before you.”

The edge in this language is personal: Having been robbed of his individuality, he brandishes his Jewishness like an ID card. This display is self-defeating, another sign that “the opposites are in control.” Revealing your claims of belonging as a Jew to be deeper than those of the state and the majority invalidates your claim to belonging in the new future of opposites.

But Naqqash also writes that “things and their opposites never disappear.” The toppling of pre-national societal order in Iraq is not presented merely as a historical transformation, and not as one defined by the emergence of suppressed ethnic hatred to the surface. It is a process that approaches the cosmic (bypassing the divine) in its magnitude, but is forced back to the terrestrial by the fact of the characters being forced to live through history linearly.

Sympathy, hatred, and misunderstanding pass fluidly across the borders between individuals. When the Jewish musician Selman Hashwah is labelled a prophet-killer by a Shi’a Arab, he immediately feels as if he is reliving the experience of the Shi’a martyr Husayn.

Aibah is the son of Gerjiyi Nati, a Jewish woman from Bombay with a questionable past who was inseminated by three men—a Jew, a Muslim and a Hindu—on the same night, leading to Aibah being described by his fellow Jews as a bastard. (“As long as I don’t know who made me conceive, all three are his fathers,” Nati reflects.)

Several passages are narrated by two characters, a technique that permits a glimpse into intimate exchanges of perspective and experience. In a passage narrated by Aibah and his friend Marrudi, Aibah is daydreaming about the past, his mind “in flames with fresh images burning with unfulfilled desire.” “I am different from them,” he reflects in relation to the “groups of noisy boys crowded on the mats at dawn” by the Tigris. “But he did not stand out at all. Then he realized with sadness, no, I definitely differ. I do.”

The passage is written deliberately to suspend certainty both as to whether this is the memory of his difference, or a retroactive realization of it—and it is not made explicit whether Aibah sees his difference within Jews, within Iraqi society, or as an individual unit entirely. As he comes to his senses, he sees that Marrudi has jumped into the Tigris in emulation of his father, in an act of escape that destroys its own trace.

Conversion to Islam is one of the solutions—along with death and flight—presented to Jews. The scenes in which Sa’idah, a young Jewish woman, converts to Islam to marry the Muslim Karim (who was previously fixated on Salimah, a Jewish nightclub singer) are among the most searingly delicate in Tenants.

Sa’idah yearns to be transported away from all the obligations of religious identity—to “escape only with love and no Ramadan and no Yom Kippur either.” But to her initial surprise, Karim has lined up her conversion, as part of his own desire to set his life in order (“no more liquor and women”) and to provide her with the appropriate place within it.

In a stunningly complex line, Sa’idah realizes that her personal desire to cement her marriage is at direct odds with her filial loyalties: “Salimah was a whore and Jewish; revenge [on Salimah, because Karim is infatuated with her] and the Koran was my other destiny.” She encounters a violent line in the Koran, and asks him who the targets—the “they”—are in it. “The Jews,” he replies, “in a natural manner.” She reminds Karim that she is Jewish. “You were,” he replies.

Karim depicts Islam as a way to keep Sa’idah’s relatives safe: In the next round of persecution, he warns her, “not even one Jew will be spared, but thanks to you, your relatives will be saved. Isn’t that good enough? … Why dig up the graves of the dead?”

Sa’idah’s mother, Farah, visits her, and observes that she has already stopped using the Jewish dialect. “I have forgotten nothing, Mother,” Sa’idah replies, blushing. “No one forgets his relatives, but I’m now used to speaking the other dialect. By the Holy Book, all of you are still in my mind.” It is unclear to Farah which Holy Book she means.

The terms of Karim’s self-interest as a member of a dominant group cannot encompass Sa’idah’s pain at abandoning her people and her faith. That possibility—of living according to your own desires under the protective auspices of the majority—is available to Muslims, but denied to Jews.

Naqqash might be our best chance of being properly haunted by the uprooting of Iraqi Jews, and of placing their experience in its fullness alongside the irreversible transformation of other 20th-century societies and the deracination of peoples. But Naqqash should not serve as a representative of a tragedy. He should rather be understood as an artist without whose talent we would be unable to see that tragedy—and its relation to other tragedies—in its fullness.

“At this point,” Naqqash said in 1996, “I am more interested in getting translated into English or French because it is only then that I will truly be able to evaluate myself. It is very difficult for a language to assess itself from within, it is only in the process of a response of readers and critics that this can happen.”

Perhaps it is only in other languages—unfreighted by the Hebrew and Arabic in which the torments of Naqqash’s life were enacted—that his work can achieve the universality that the writer yearned for.

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.