Down and Out in Yidsbury

How I sat out the Vietnam War in an English department in Manchester, England, only to come home to another battle in New York

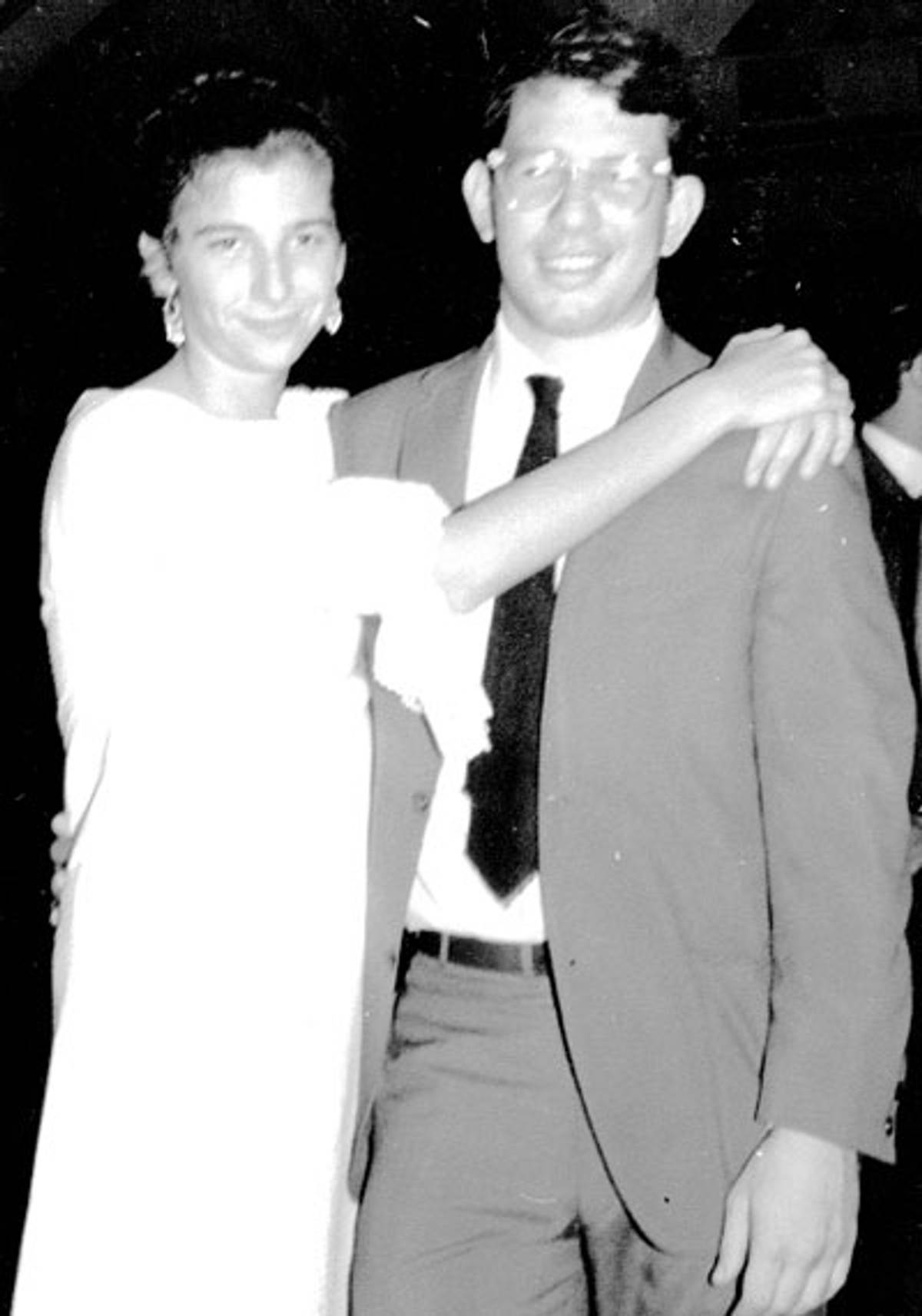

In the fall of 1964, about two months after my wife, Eleanor, and I settled in Didsbury—known as Yidsbury, a suburb of Manchester, England—my mother phoned from Huntington, Long Island, to say that a letter for me had arrived from my draft board instructing me to show up for a physical exam to determine if I was fit for service in the U.S. military. (It was called Yidsbury because of the sizable Jewish population and the Jewish delicatessen where I bought British bagels, cream cheese, and smoked salmon.) I had not moved to England and enrolled as a postgraduate student at the redbrick University of Manchester to avoid the draft, but now that my induction into the armed forces seemed imminent I wrote home to say that I was living abroad with my wife and pursuing a Ph.D. in English literature. Before long, I was assigned a “2-S,” a student deferment, which meant that I wasn’t drafted that year, 1964, or in 1965, 1966, and 1967, when I returned to the States with a degree and a teaching position at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

That first fall in Manchester came without Halloween and Thanksgiving, though we did celebrate Guy Fawkes Night on Nov. 5 with fireworks and a bonfire to honor the memory of the conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot of 1604 who planned and failed to blow up the Houses of Parliament. The English had strange customs, including the queue where everyone got on line and no one jumped ahead, which was at the core of their much-vaunted civilization. The last Thursday in November felt awfully lonely without family, friends, and mounds of food, but Eleanor and I created our own mini holiday. The 17th-century Puritans would have approved.

At the University of Manchester I met weekly with my tutor, R.G. Cox, a follower of F.R. Leavis, who sometimes snoozed while I read aloud the essays I wrote about Plain Tales from the Hills, Kim, Nostromo, and Heart of Darkness. I hoped that my essays for “R.G.” would find their way into my thesis on British literature and the British Empire, which professor Frank Kermode, the star of the English department, called “Bolshie,” but which he also encouraged. After all, I built my work around T. S. Eliot’s observation that Joseph Conrad was “the antithesis of Kipling. He is, for one thing, the antithesis of Empire.” Kermode couldn’t argue with Eliot. While I was at Manchester, Kermode was writing The Sense of an Ending and would read chapters to students, which distinguished him from my lofty professors, including Lionel Trilling, and F.W. Dupee, at Columbia College who were fighting the ideological battles of the 1930s in the late 1950s and early 1960s when I was an undergraduate in the English department.

During the three years that Eleanor and I lived in Manchester we didn’t own a car, a bicycle, a telly, or a refrigerator, though we did own a battery-operated radio and listened to the BBC and Radio Luxembourg, which had a certain mystique. At the start of our third year, we bought a small record player so we could listen to Bob Dylan and the Beatles and the Stones, but we were distinctly bookish. Eleanor read aloud from Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and so I met Frodo, Gandalf, and Strider. We were not intentionally trying to live simply. It was just that we didn’t have much money, although I received a research studentship in the arts and 200 pounds a year, which went a long way. I had no fees to pay at the university. We felt that we didn’t need a car, or many of the basic appliances we would have had if we had stayed in New York.

We read The Guardian and The New Statesman, especially Andrew Kopkind’s reports from the States, and felt that we were well informed about the war in Vietnam, and the opposition to it, and savvy about British politics, which had taken a turn to the left, or so it seemed, when Harold Wilson became the prime minister soon after we arrived in Manchester. A student party to celebrate the Labour victory was the first we attended in the city. On one occasion, I gave a talk about the British Empire and British literature to members of the Manchester Communist Party and disappointed the comrades who attended. “What about the workers?” one man asked. I had told them about Mr. Kurtz, Marlow, Nostromo, and Kim, hardly working-class chaps.

For our first two years we lived on the top floor of a semidetached house in Didsbury, about 35-40 minutes by bus from central Manchester, though on evenings thick with smog and fog that same journey could take two hours. Like most of our neighbors, we contributed to the atrocious quality of the air. Until it was banned in 1966, we burned soft coal and thought nothing of it, except that in winter it was hard to heat our two small rooms and the tiny kitchen at the top of the flight of stairs. Eleanor suffered from chilblains. I shivered. Our last year we rented the ground floor of a large house with a front yard, but that didn’t have a “cooker.” That was our one big purchase the whole time we were in Manchester, though I did splurge and buy a herringbone tweed jacket from a tailor in Didsbury.

I didn’t think of myself as an expat, or an exile, but rather as a “Yank” in part because that’s what neighbors and chums at the university called me. I didn’t acquire a British accent, but I was an Anglophile and in awe of Henry James and T.S. Eliot. An empire in decline had a certain charm, unlike an empire with claws and fangs. My wife picked up a Manchester working-class accent and used it when she chose to pass for a Mancunian. She also received a “first” in American studies and wrote a thesis on The Masses, the radical magazine that was shut down by the U.S. government during World War I. All of Manchester seemed working class with mile after mile of little red-brick houses that looked alike, but that gave birth to unique footballers and local poets, like Tony Connor who became a pal and who would say, “A poet at 16 is 16, a poet at 61 is a poet.” He also worked at a Manchester synagogue on the Sabbath when Orthodox Jews were not supposed to work, “not even turn on a light switch,” he explained.

I remember asking Mrs. Cohen—a middle-aged decidedly Jewish woman who was born in Canada and who adopted Eleanor and me—“Are there any wealthy people in Manchester?” She replied, “Where there’s muck, there’s brass.” Another of her expressions was, “Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in two generations.” Even when the opera came to Manchester from London’s Covent Garden, the city seemed solidly working class. No one dressed up in furs and jewelry, but rather wore the same clothes to hear The Marriage of Figaro they wore to work. Indeed, audience members came right from offices, factories, and the university, which made opera in Manchester look, sound, and feel better than opera at the Met in New York.

Most of our friends weren’t English, but rather Irish, Scottish, and Welsh. Almost all of them were folk singers or part of the folk music revival of the mid-1960s that drew us to the likes of Peggy Seeger, A.L. Loyd, and Ewan MacColl, whose song “Dirty Old Town” could have been about Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, and so many of those northern English places where Eleanor played the guitar and sang the blues in pubs and clubs. When the promoter, Mike Stevens, asked her if she was from Greenwich Village or Harlem—the only two neighborhoods he knew of in New York—she said, “Neither.” Mike decided that Harlem sounded better than Greenwich Village and advertised “Eleanor Raskin as an American singer from Harlem, U.S.A.” which prompted African American servicemen to show up, and to be disappointed not to see a black woman on stage.

On Sundays we played bridge with Serena Sugar and her husband, Patrick, who usually played the wrong card and who received a rebuke “for sending a boy on a man’s errand” or “for sending a man on a boy’s errand.” Patrick would laugh and recite Robert Burns or talk about his favorite novel, Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis, which appeared in 1954, but that 20 years later still seemed to capture much of the spirit of academic life at a red brick university. In the mid-1960s teaching jobs were hard to come by, though Patrick and I did some teaching at a conference for students held by the journal Critical Quarterly after the editor, C.B. Cox, joined the Manchester English department. My friend Michael Wilding, who attended Oxford and with whom I shared a passion for Joseph Conrad, would say that his peers “were waiting for old men to die so they could step into their shoes.” Michael gave up waiting, moved to Australia, taught English at the University of Sydney, and wrote fiction and literary criticism.

Most of my travel was on the number 42 bus, which took me from Didsbury to the university on Oxford Road and to central Manchester, where I used the library, ate curry, and after a while discovered the Shambles, where we devoured the most wonderful oysters. Eleanor and I soon learned that an invitation for afternoon tea could mean just tea, or tea and crumpets, or tea, cakes, and little sandwiches. On Saturday nights we saw international movies that were screened by the Manchester Film Society, and on Sunday afternoons we went to the cinema in Didsbury, in part because it was the only place that was open on Sunday afternoons.

Andrew and Margaret, our landlord and landlady, took us hiking in the Pennines, and a couple of times a year we hitchhiked back and forth from Manchester to Cambridge, where our Yank friend Michael Meeropol, the older son of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, was studying economics at King’s College. He, too, was a folk singer. The novelist, E.M. Forster, had rooms beneath Michael’s and wrote notes to complain about “the noise,” which prompted Michael to make more noise on his guitar so he might receive more handwritten notes, which he treasured. Foster soon caught on and stopped writing while Michael played quieter. Eric Foner, whom I knew from Columbia College, was at Oxford on a fellowship. He would join us. We all shivered together. Meeropol refused to feed the gas heater and give it the satisfaction of eating his pennies and shillings.

I tried to become English, or what I thought was English, which meant smoking Gauloises and a pipe, and wearing my tweed jacket, but I never did like to drink pints of bitter, and I never did become a fan of Manchester City or Manchester United, though those were the glory days of Bobby Charlton and George Best. That much I knew. The year after we left England, Manchester United won the European Cup. By then we were loyal fans of English football.

In July 1965, we flew from Manchester to Milan for about $50 round-trip, and spent much of the summer attending antiwar demonstrations in Italy and collecting antiwar leaflets and posters which attracted the attention of the authorities when we returned to England. I was pulled off the coach that was to take us from Dover to London and questioned about the “literature” in my suitcase. I had also covered a tattered paperback titled Writers on the Left by Daniel Aaron. That seemed suspicious to British custom agents. “What was I trying to hide?” That was the idea. After a couple of hours, I was allowed to board the bus and rejoin the other passengers who were eager to get on the road. What I wanted most of all, after the summer on the continent, was a proper English breakfast and a proper English cup of tea with milk and sugar.

A Ph.D. from Manchester wasn’t a big deal in Manchester, but it was in the States, especially when I explained to American academics that I had my own personal tutor for three years. What I didn’t share was that the doctoral program was much more stressful than I expected it would be. In the office of professor John Jump, the head of the department, I felt under scrutiny. In the Central Library I would occasionally feel that my heart was racing, or skipping a beat, but when I went to see a heart specialist—I was covered under the National Health Service—he listened carefully with his stethoscope and pronounced me physically fit. That was my only visit to an English doctor during my three years in Manchester.

When I asked for something to make me feel better, the doctor wrote a prescription for a “placebo,” as he called it, though he insisted that since I knew it was a placebo it would not help me. I went back to the flat where I lived, placed the Rx in the top drawer of my dresser and never experienced an irregular heart beat again, not until I returned to the States, which struck me as a strange country, populated by hippies, Yippies, Diggers, and all manner of ’60s characters aiming to undo the American empire their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents had so painstakingly built.

Looking back at Manchester in the mid-1960s, it strikes me now that it was a kind of 19th-century English fairy tale. New York had its blackout and Watts its riots. Malcolm X was assassinated and Dylan went electric. Manchester followed the road it had taken decades ago, if not longer. The official name of the university I attended was the “Victoria University of Manchester.” Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865) was the most famous local author. Pizza had not yet arrived and the bobbies (the police) mostly behaved like gentlemen in uniform.

For a glimpse of the 20th century and its fashion I had to go to “Swinging London,” where I bought bell-bottoms and lawn shirts on Carnaby Street. After three years in England, I was a kind of dandy. My only rebellion was not to stand in movie theaters when the British National Anthem, “God Save the Queen,” was played. I have never appreciated the British crown and British aristocrats.

Thanksgiving was not celebrated by the Brits when I was in Manchester, and as far as I knew Eleanor and I were the only Yanks in the whole city. In London we went to Fortnum & Mason, bought American goodies, brought them home and celebrated Thanksgiving in our flat.

On a personal level, married life in Manchester was life in a cocoon without pressure from family and peers. Matthew Arnold’s poem “Dover Beach,” published in 1867, expressed my sentiments, especially in the line, “Ah, love, let us be true/ To one another!” and then again in the closing where the poet describes: “a darkling plain … where ignorant armies clash by night.”

Returning to the U.S. meant the end of the Manchester idyll and a rapid descent into the “darkling plain” where those ignorant armies clashed. The only remote facsimile of a sanctuary was our two-bedroom apartment at 250 Riverside Dr., which was soon invaded by SDS members. Riverside Drive was a 15-minute bus ride on Broadway to Columbia Law School, where Eleanor was a first-year student. It was a 75-minute drive on the Long Island Expressway to Stony Brook where I was an assistant professor, teaching Victorian poetry and the Victorian novel in an English department top-heavy with New York intellectuals like Alfred Kazin.

I would ride to and from work with Alfred in his Nash Rambler; the car spoke well for him. The front seat turned into a hot house of ideas and issues. Alfred loved a fight. When I expressed admiration for Eldridge Cleaver and Soul on Ice, he called Eldridge “a professional black man.” I took umbrage, as the British would say, though before long I came around to Alfred’s perspective. Would he mind if I called him “a New York Jew”? I asked. He said he would, though he called his 1978 autobiography New York Jew. After he read the manuscript of my first book, The Mythology of Imperialism, he called me “a Marxist Leavis,” and added, “You can’t use that as a blurb.” He protected his reputation and his name and gave himself permission to say things about himself he would never give to me or anyone else.

To be in New York in 1967 meant to be in a Jewish city, surrounded by aunts and uncles who had chutzpah, loved to kibitz, and insisted on taking Eleanor and me to eat borscht and blintzes at the 2nd Avenue Deli. Being in New York felt like being at the cultural and financial center of the world, in much the same way that Manchester had once felt like the center of the industrial world and then turned into a backwater.

In New York, Max’s Kansas City was the place to see and be seen, the Lower East Side the happening neighborhood and Columbia “the” campus where revolt lurked under the academic surface, ready to explode. Nearly everything about New York said: “Welcome to the mad, bad, sad ’60s.”

Jonah Raskin, professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of 14 books, including biographies of Jack London, Allen Ginsberg, and Abbie Hoffman. His new book of poetry is The Thief of Yellow Roses (Regent Press).