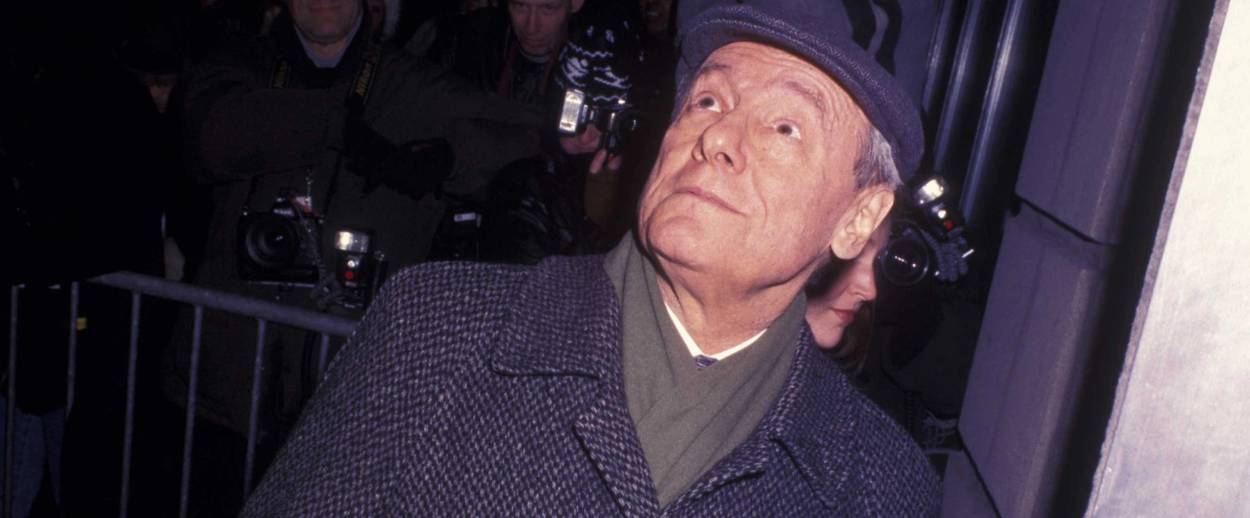

The Real John Simon

Did the late, splenetic theater and film critic take a secret to his grave?

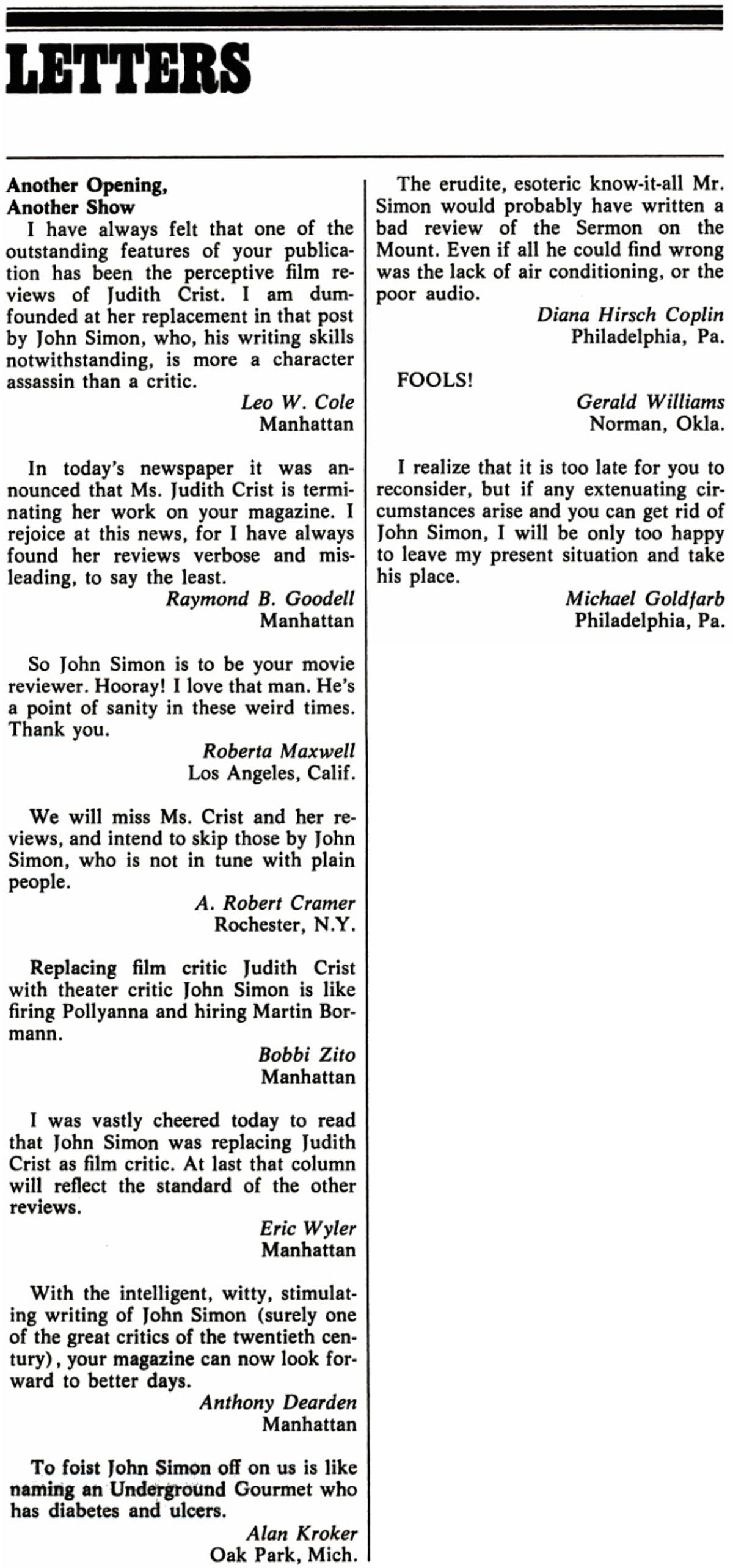

The announcement of John Simon’s death late last year was greeted in the New York arts community much like VE-Day was by the general public in 1945. While I have yet to see pictures of sailors on shore leave kissing random women in Times Square, my guess would be that most of the Theater District’s denizens are even more elated. No critic was so hated.

Yet amidst the plethora of raised glasses and joyous toasts, defenders have come forth, insisting that the animus he engendered was a consequence of his dogged belief in artistic standards.

Lost amid this predictable back-and-forth is one story of who Simon really may have been and what he in fact accomplished. Did he successfully conceal his true, traumatic origins through the length of his adult life? None of his obituary writers mention it, yet if true, it would have affected him greatly. It’s a Broadway story revealed here for the first time. It certainly would explain a lot.

Was John Simon an impostor? While he presented himself as a gentile from Serbo-Croatia, as his surname suggests, his father may have been Jewish, sent to the United States in fear of what Hitler might do to him. And was there an even darker and more painful secret that Simon kept hidden? Simon had a half-brother, who did not get out of Europe in time and was murdered by the Nazis.

How can I suggest this?

It happens that I have a career as a playwright, and one of my early champions was the late, longtime Daily News theater critic Howard Kissel, who for decades was Simon’s best friend. As I had always enjoyed and admired Kissel’s reviews and was grateful for the kind things he had written about one of my first plays, after he retired I asked him to lunch, explaining that he could not say that I was trying to win his favor now that he was no longer going to be composing theater columns.

Howard and I would occasionally meet up to chat and we frequently ran into one another at the Metropolitan Opera or Carnegie Hall. Then, in 2010, Howard was diagnosed with hepatitis. Its source was a blood transfusion that he had received in the mid-1970s. Because of the illness, he was in and out of hospitals. As I very much enjoyed his company and had come to be extremely fond of him, I think I spent as many hours with him during the final two years of his life as anyone other than his sister.

This was also a period when Kissel decided that Simon was not the friend he had supposed. Turning on Simon, Kissel began telling me many stories, including this version of Simon’s ancestry and of his brother’s death. (Howard also had some gifts of mimicry, and he did a very amusing impersonation of Simon.) Simon’s sister could not be reached for comment.

I should say here that Simon reviewed my work once. As was his habit with anyone starting out, he provided a slashing pan. It was for my play The Germans in Paris. The notice would not have greatly bothered me save for one thing: The play was loved by audiences. In fact, it was actually the single highest rated show by audience survey in New York on the Theatermania website during its run. Hence, both of its productions sold out, the first of these exclusively based on word of mouth. Simon had come to see it on one of the nights when we had an especially enthusiastic response—laughter all evening long. Obviously it’s perfectly appropriate to have an opinion at odds with the audience. However, as someone who has written plenty of reviews myself, I know that a good critic makes at least passing acknowledgement of this, especially if the work has not been widely seen. Simply put, he had broken an unwritten rule of the art, in a way that seemed pointlessly mean.

John Simon’s most enduring legacy may have been to encourage a style of boorishness in public life which has reached its apotheosis at the moment of his passing.

Simon’s trademark nastiness and failures of character made him deficient as a critic. Nonetheless, there can be no doubt that he had read a vast amount in many languages, and he was determined in his efforts to be a man of culture. He was also extremely witty, and his voice and acidulous personality were never absent from his writing. The result could be quite amusing. If nothing else, he was almost always a fun read. One can cite plenty of terrific lines to his credit. (For example, “Like springs, adaptations can only go downhill.”)

Did John Simon offer something more than cleverness, though? Was there lasting excellence and insight in his writing—or at least a valuable perspective that offered useful guidance?

Certainly, there was an amount of judgment with regard to playwriting. But whether his play reviews are still worth reading, I’m not sure. Moreover, on almost every other subject his opinions were dubious, at best. His writing was marred both by his spectacular meanness and his unbridled egotism. That latter trait attached itself in a peculiar fashion in his response to his ancestry.

People hide their Jewish roots because they are ashamed of their Jewishness. I suspect that Simon’s experiences had persuaded him that Jewishness was a particularly dangerous kind of weakness, and in his vanity, as well as for perceived reasons of self-protection, he chose to identify himself with his oppressors. That which was Aryan was good, and in his mind he was not only its advocate but a kindred soul.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Simon first made his name as a critic through his promotion of the erstwhile art-house Nazi, the Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman. Simon’s writing about Bergman is startling for its fatuousness. There can be little doubt but that Bergman was capable of great filmmaking: One has only to think of movies like Summer With Monika, Wild Strawberries, or Autumn Sonata. Yet these were not the films that Simon praised. Rather, he celebrated the worst of Bergman’s tedious exercises in pomposity and pretentiousness, deservedly forgotten motion pictures like The Silence and Hour of the Wolf.

In setting forward these “standards,” Simon was establishing a template, a pattern of taste that would carry through the rest of his career. Whatever was admired by the most recondite of European highbrows, he admired. Whatever was liked by New York Jews, he despised.

Thus, Barbra Streisand was “the sort of thing that starts pogroms,” and the Jewish-looking Liza Minnelli resembled “a beagle.” Wallace Shawn was “unsightly.” Annie Hall was “so shapeless, sprawling, repetitious and aimless as to seem to beg for oblivion.” Everything that David Mamet wrote after his first two one-act plays was “the same thing rehashed over and over, and no longer news.” (This included American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross.) Simon was rueful that political correctness had made it impolitic to call something a “faggoty Jewish musical.”

It also negatively affected his taste in ways which are not so obvious.

I think we can reasonably assume that Simon was not tone deaf. It would be hard to explain the enormous amount of time he spent listening to and commenting on music if he were. Yet his opinions about music were perverse, bizarre, and generally idiotic.

What was his taste? Here’s how he put it:

I recall a conversation with a minor conductor. MC: Do you like Bach? JS: Not at all. MC: How about Mozart? JS: Ditto. MC: Beethoven? JS: Hardly. MC (exasperated): Do you like music? JS: Absolutely.

Then there is a hostile review of my book John Simon on Music, written by Alan Rich. We knew each other quite well without any love lost. Rich was outraged about there being in it only one mention of Mozart, and even that in a quotation from someone else.

Well, there it is: I don’t like any music before some Schubert, and not even all of his. What is all this about? Let me try to explain …

It appears to me that Bach and Mozart (Beethoven was somewhat different) wrote predictable, mathematical music, limited in scope, not unlike a caged canary’s pleasant but anodyne chirping. It was also perfectly square, by which I mean that from the first two notes of a bar you could predict the next two. Beethoven was, at any rate, impassioned, but not in a fully melodious way.

There were, of course, changes in rhythm and dynamics, and some very modest surprises. But even when the music deigned to be fast and loud, it was still wallpaper to me, which, after all, can also be loud and repeats its pattern rapidly. …

There is no ecstasy, a sense of pathos even in the lighter colors, a stirring up of one’s feelings, beauty so intense that it almost hurts. There isn’t that mercurial quality of sudden changes from comedy to tragedy, a rhapsodic freedom to roam into supermelodiousness, into stirring harmonies and polyphony, into guarded poly- or atonality, into tunefulness that approaches the orgasmic as it fluctuates between gossamer and a kind of endearing grandiloquence. What can I say? Modulation, chromaticism, rapture …

What all of these earlier composers have in common is that they were beloved by the New York Jews (and Asians) that Simon considered himself far above. In their place, he created his own pantheon. Some of its figures, like Richard Strauss, were genuinely great. What they have in common however is that they reflect recondite tastes and interests, and they are gentile. Simon had no use for Korngold or Gershwin. Among Simon’s favorite composers instead was the obscure (and almost completely impossible to listen to) Frank Martin, a properly unknown 20th-century Swiss music-maker.

Similarly, many of the novels he expressed special interest in were not so much good as representative of a self-important sensibility and special knowledge. Thus, he especially adulated Samuel Beckett’s novels.

This habit of emphasizing minor but little-known works reflected his deficits of soul. In his unsurpassed book about Broadway, The Season, William Goldman spoke of this problem in describing what he called the “supercritic.” He explained it as, “a critic who places the value of his own writings above that of the art object. … They are predictable through the use of quiz psychology. Are the early notices of a novel splendid? The supercritic will pan it. He has to.”

Simon was the supercritic par excellence. He had many of the qualities that a good critic requires: high intelligence, wide learning, a broad base of knowledge of the arts, perspicacity, and wit. And he was not infrequently right.

But what he was lacking was vital.

To understand this, you must first understand that outstanding critics are very rare, much more uncommon than first-rate practitioners in any given art form. That’s because outstanding criticism requires 90% or more of the knowledge needed to excel as a practitioner—plus humanity and judgment. Consider the novel with regard to this. One could make a long list of gifted novelists who were largely devoid of either or both. I think it’s safe to say that Balzac, Dostoyevsky, and Hemingway lacked judgment and would not have been good critics, and that Waugh, Greene, and Roth lacked degrees of normal human empathy. Yet a critic of the novel needs all these things.

Anyone who knew Simon can provide you with countless tales of his pettiness and cruelty. I think, for instance, of a director friend of mine who used to go on double dates with Simon when the two were both single. After my friend married an actress who was in the process of becoming a playwright, he contacted Simon. Thinking he was doing his wife a favor, he showed him a draft of one of her plays. Simon responded by dressing her down to her face and suggesting that not only was the play no good but that she might be devoid of any talent as a writer. Yet she has since received award nominations and raves from eminent publications, including The New York Times. Simon never bothered, of course, to attend one of her shows in order to make up for his prior ill manners.

Those who defend Simon insist that he “upheld standards.” But, even if he performed that task, he failed in so many others that it becomes difficult to suggest that he served the interests of any art form terribly well. While he wrote about many artists in many fields it is almost impossible to name a work of art, a major artist, or an artistic movement whose legacy would be unknown or unappreciated in his absence. Although Anthony Blunt was a traitor, he provided a new level of appreciation and understanding to the work of Poussin and made a definitive study of the artist. Simon may not have been as shabby a man, but he left us nothing like that. Indeed, his most enduring legacy may have been to encourage a style of boorishness in public life which has reached its apotheosis at the moment of his passing.

Moreover, because Simon was out of tune with humans, he was notoriously incapable of distinguishing good acting from bad. Any actress with Nordic looks was likely to be judged as superlative. Thus, Uma Thurman was “scintillating.” Yet Philip Seymour Hoffman always left much to be desired.

Nor did Simon ever manage to write a book worth reading. He attempted to explain this by saying that he was “a sprinter, not a marathoner.” But at least three of his contemporaries among theater critics did. Just off the top of my head, I can think of Terry Teachout’s biography of Louis Armstrong, Kissel’s tell-all about David Merrick, and Martin Gottfried’s histories of the Broadway musical. These superb books were inspired by their authors’ love. Simon’s inability drew from his absence of that emotion. What he wrote was always, first and foremost, an advertisement for himself. He was incapable of that level of devotion to another person’s achievements.

I suspect that Simon’s defects as a man would have existed in some form with or without the specter of the Holocaust, although they might well have taken a different form had he not suffered the terrible familial misfortunes and dislocation that he did.

The most remarkable and most widely remembered instance of Simon’s nastiness was likely the incident when he was overheard at a theater saying that he hoped AIDS “kills them all,” meaning gays. To his credit, he did not deny having said it. He was fortunate professionally in that he lived before “cancel culture,” and his career continued for decades after that. But one must ask: If you lived through a Holocaust and saw a brother wiped out in it, how could you wish for another?

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jonathan Leaf is a playwright, journalist, and critic.