The Jewish Disney Family of Egypt

A new documentary traces the rise, fall, and amazing rediscovery of the world’s first Arab cartoon star

Making documentary films about artists is always a tricky task, especially when it comes to finding the right balance between focusing on the artists and on the art. A successful example of such balance can be found in last year’s documentary Bukra fil Mish-Mish, directed by Tal Michael and currently showing in Israeli and global festivals. The film tells the story of the Frenkel bothers—Herschel, Shlomo, and David—who singlehandedly pioneered the art of animation in Egypt and the Arab world. Although the mid-’90s saw a surge of renewed interest in the Frenkel brothers and their work by scholars of Arab cinema, Michael’s film reminds the audience that their story is, first and foremost, a very Jewish story.

The Frenkel family were wandering Jews. More specifically, they were Russian Jews who fled from the pogroms of the early 20th-century Russian Empire to Palestine, only to be banished from there to Egypt by the Ottoman regime following the outbreak of World War I.

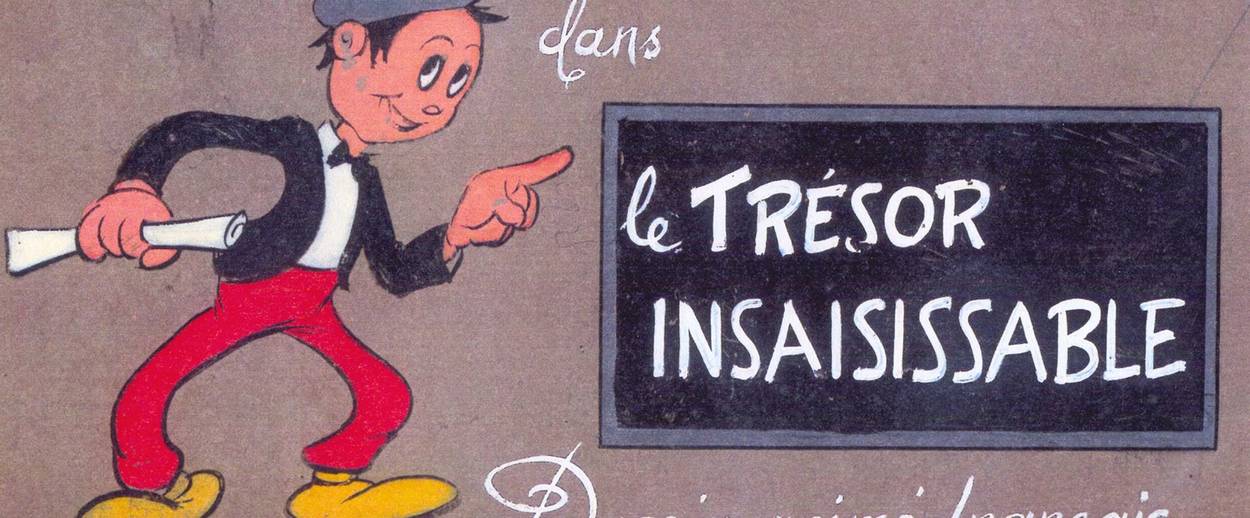

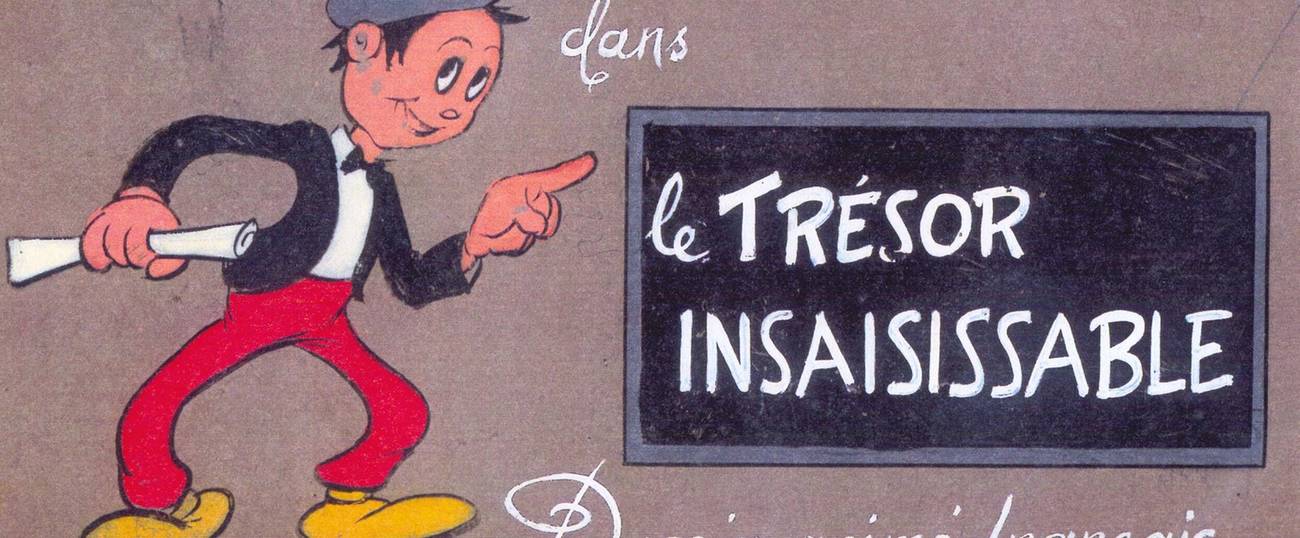

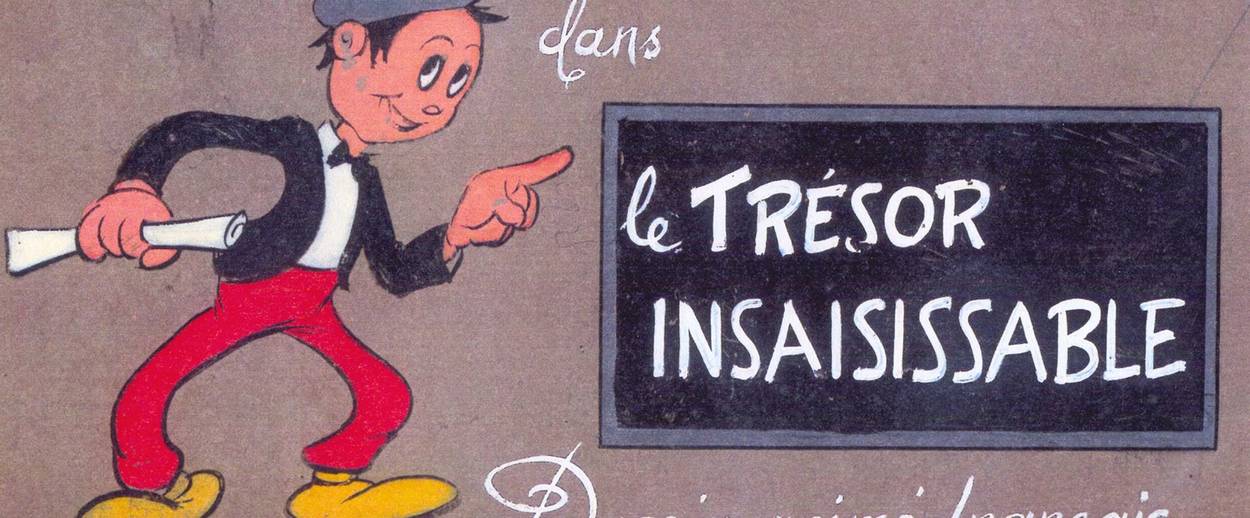

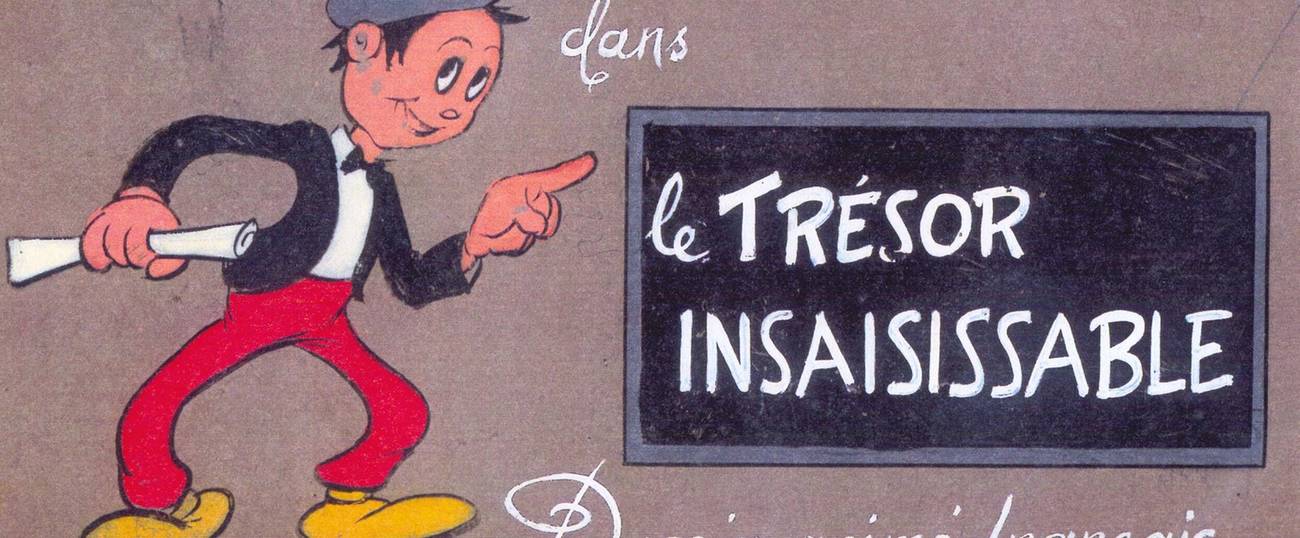

It was in Egypt, the country to which they were banished, and to which they had no preexisting linguistic or cultural connections, where the Frenkels found their greatest success. Inspired by early American cartoons and silent comedies, the three brothers released their first animated film in 1936, creating an instant landmark in the history of Egyptian and Arab cinema. The film’s title, “Mafish Fayda,” literally means “it’s useless,” and is rumored to have been inspired by the reaction of a potential investor to the brothers’ request to finance their film.

The protagonist, Mish-Mish Effendi, is prone to the same slapstick mishaps typical of Hollywood cartoon characters and film comedians, yet he is unmistakably a person of Egypt of the 1930s. He wears a fez on his head, and is ready to enjoy the good life offered by the streets of Cairo of that era, where traditional architecture and desert landscapes come together with modern vehicles and recreation spots, especially when he is trying to woo a beautiful woman in a revealing Western outfit. As noted by an animation scholar in Michael’s film, the physicality of the woman’s character in the Frenkels’ film was clearly inspired by American cartoon star Betty Boop, which was created by the Fleischer bothers—another Jewish family that found success in the animation field, only to see it slip away as social circumstances changed.

Mish-Mish would go on to become the first Arab cartoon star, and several of his films included live-action footage of the Egyptian entertainment industry’s greatest film and music stars, who were proud to be pictured alongside him. As success grew, the Egyptian authorities took notice and asked the Frenkel brothers to produce educational films and propaganda pieces aimed at supporting the government in the wake of WWII. The Frenkel brothers were only too happy to comply: They believed that in Egypt, a cosmopolitan paradise in the 1930s, they had finally found their true home.

Alas, with Israel’s declaration of independence the Frenkels found themselves again banished from their country. As Michael’s film reveals, the brothers actually considered leaving to Israel, but doubts about their ability to continue film production there made them decide on settling in France, which they believed would be friendlier to their professional efforts. That decision would be proven very, very wrong.

It is here that the Frenkels’ story takes a more personal, though equally fascinating, turn. The unsung hero of the family’s attempts to survive its latest exile, it turns out, is Shlomo Frenkel’s wife, Marcel, who resents the brothers’ insistence on continuing to produce their animated films in France, even though it was clear that they had no real audience or financial backing there.

Bukra fil Mish-Mish opens with Shlomo’s son, Didier, and his quest for preserving materials from his father’s and uncles’ estate, but Marcel dismisses his efforts: For her, these materials represent a pursuit of dreams that never came true, a foolish chase that forced her to take on the burden of supporting not just her husband and children but also her brothers-in-law. At one point in Michael’s film, Marcel muses how her different background—coming from a Jewish Sephardi family, as opposed to her husband’s Ashkenazi heritage, may have contributed to her insistence on keeping her feet on the ground while the Frenkels stubbornly kept their heads in the clouds.

Yet despite its utter commercial failure, the Frenkels’ work in France deserves equal if not greater artistic recognition than their work in Egypt. Michael’s film includes brief clips from two of the Frenkels’ films of the era. One is a 1954 science fiction short titled Atomic Adventure, which appears to be highly influenced by the Fleischer brothers Superman films. The other is The Beautiful Blue Danube Dream, a romantic musical reminiscent of high-end Disney films. Beautifully designed and animated in lavish color, both productions look technically superior to the brothers’ earlier Egyptian efforts, and show how, even as their families struggled to support themselves, they never gave up on their artistic ambitions.

Bukra fil Mish-Mish leaves its audience with the tantalizing apprehension of a glorious chapter in animation history and Egyptian film history and also in Jewish history that is waiting to be revealed. Yet the film eventually offers us only a few brief glimpses of this promised cartoonland. Even though the Frenkels’ films have received some wider recognition since the 1990s for their historical importance, the brothers’ huge output remains almost impossible even for animation buffs to access. Michael’s film is probably your best chance to get acquainted with their work.

Bukra fil Mish-Mish can be watched online in some countries in a shortened version, courtesy of the Israeli Broadcast Corporation, with Hebrew subtitles; the full version, with English subtitles, is currently making the rounds of film festivals. Here’s hoping that the release of this fine documentary will lead to the restoration and availability of the Frenkels’ entire catalog—a treasure that awaits fans of animation and of Arab and Jewish history alike.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Raz Greenberg, an animation researcher, is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator.