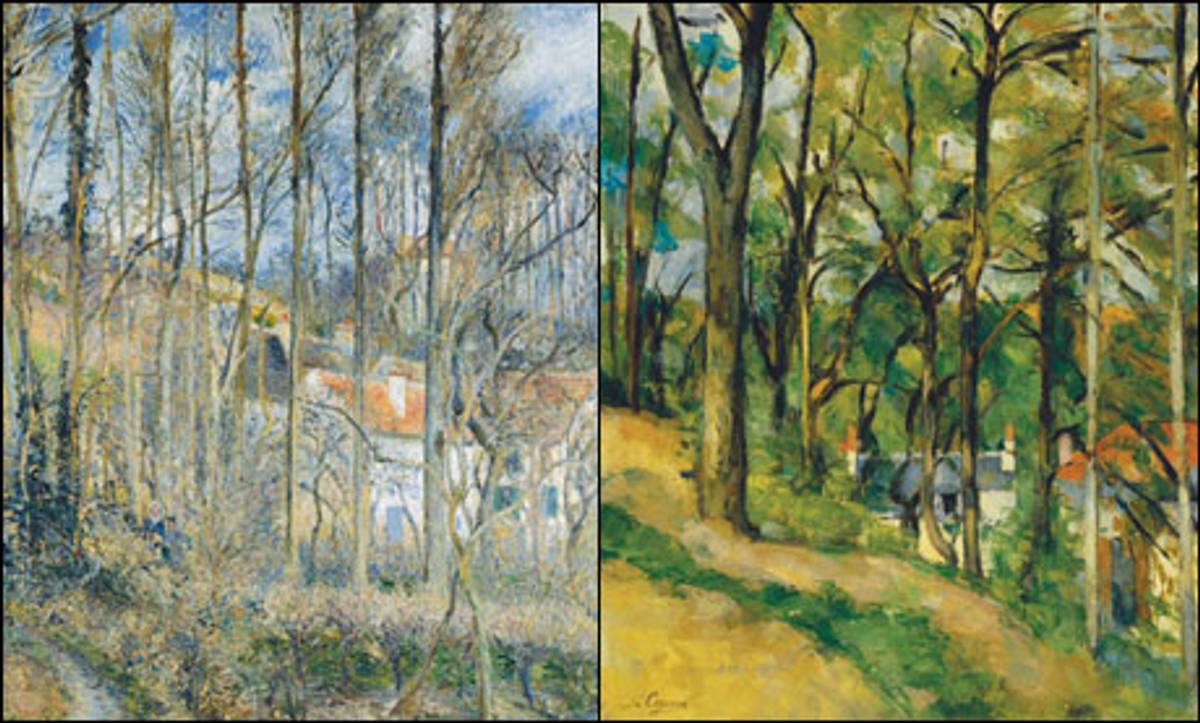

Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne were both outsiders to the Paris art scene when they met in the early 1860s. Their intense personal friendship and artistic dialogue lasted for two decades, refining the language of Modernism and producing some Impressionist masterpieces. Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865-1885, which opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on October 20 and runs through January 16, chronicles how they painted side by side and evolved in response to each other’s work. The exhibition originated at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it was organized by Joachim Pissarro, a curator in the department of painting and sculpture—and the artist’s great-grandson.

In the press release for the MoMA show, Pissarro is identified as coming from a Jewish family on the island of St. Thomas, yet Cézanne’s religion is not mentioned, just that he came from a banker’s family in Provence.

I got a few letters about that. That’s a very good point. I use the term “Jewish” in its cultural, almost anthropological sense rather than its religious sense, because Pissarro was never religious. If I would have discussed the later Cézanne, I probably would have brought up Catholicism. But in the early days, they were both true anarchists, and the notion of Catholicism was not relevant, no more than the religious sense of what Judaism means to Pissarro.

How do you define Pissarro’s cultural Judaism?

The context in which Pissarro was born was very free, religiously speaking. St. Thomas was one of those free ports in which it was allowed and accepted to be anything. But at the same time, he was born to parents who had broken the laws of Judaism.

Because his widowed mother fell in love with her nephew by marriage, who had been sent from France to help the family. And the synagogue refused to recognize their union.

It was like banging on the doors of the temple and saying, “Let me in.” It took them eight years to get their marriage recognized. It was not recognized by the rabbi, it was recognized by the King of Denmark.

Pissarro ran away from this. He lived in a rural French village where there probably wasn’t a single synagogue. I doubt the people there even knew what Judaism was. He didn’t have a problem with being Jewish. But he did not do anything at all about it. You could say he defined himself against the religious aspect of Judaism. He very much tried to make sure that his children would not practice any kind of religion.

It is also an interesting question of what kind of religious background was passed on. There is a letter in which his father begs him to come for Yom Kippur. The letter is bizarre because Pissarro is in his early twenties, and his father explains what Yom Kippur is. Culturally speaking, there was really nothing much coming from his family. He is in contact with his mother of course—

But his mother wouldn’t talk to his wife, who not only wasn’t Jewish but also was a cook’s assistant. So was that the end of Judaism for Pissarro’s descendants?

He was in contact with his sister, who was married to a Jew, probably an Orthodox Jew, in London. Then his son Lucien fell in love with an English girl of an Orthodox background. Her parents said, if you want to marry our daughter, you have to convert to Judaism, so the son writes this letter pleading for the father’s help. And of course Pissarro says, this is totally grotesque, you are not going to do any of these stupid things. He eventually goes to London to sit down with the parents and try to convince them his son is a good anarchist, he is very upright and morally ethical as all anarchists are. Eventually, the young couple eloped and married in a city hall without a religious ceremony.

And the descendants now?

My brother and my sister converted to Judaism to marry Jews. My sister, who is an artist, lives in London, she’s married to an Israeli. And my brother, an art dealer, converted to Judaism to marry my sister-in-law. They live in Paris.

Even though you are Pissarro’s great-grandson, you had no intention of studying his work.

I had never really looked at my great-grandfather’s work with any particular interest. To me Impressionism—I see this attitude in many of my students—was pretty, candy-box imagery. I just ran away from it. But then, when I came out of the Courtauld Institute with a 20th-century art background, I was offered this major job through the dealer Daniel Wildenstein to work on the catalogue raisonné of Pissarro’s work. And I discovered Pissarro was not only a very interesting artist but an artist who had remained largely undiscovered. Whole chunks of his work were really unknown.

You attribute Pissarro’s friendship with Cézanne to their shared feeling of otherness, which is also expressed in their art.

This goes back to the idea of cultural Judaism. You might say that the role of the outsider in society is a role that is traditionally assumed by Jews. In this sense, Pissarro remains very much a Jew in French society.

Oddly enough, you might also say the same thing about Cézanne, even though Cézanne is not a Jew. They had this kind of magnet attraction to each other. They recognize each other in their status as outsiders in society. You can see that in their images of each other and themselves.

Take Pissarro’s 1874 portrait of Cézanne. One of my students asked me, Was Cézanne Jewish? It is very funny. You see him with this black cap, he could be a Central European Ashkenazi Jew.

How does this picture portray Cézanne as an outsider?

Cézanne was—physically speaking, linguistically speaking, apparently in his body language, in every possible way—a weirdo. At the same time, he was a brilliant guy. Pissarro very much respected this complex nature of Cézanne. He lovingly portrayed him as all these things.

And when Cézanne painted Pissarro, what did he depict?

The way I see it is that what appealed to Cézanne in Pissarro was not just that they were both outsiders, but that Pissarro was a missing father for Cézanne. Cézanne is absolutely desperate for recognition, which he doesn’t get anywhere. Even from his very best friend—Zola is clearly not taken with Cézanne’s art. There is only one guy who sees in Cézanne great qualities artistically.

And from the human point of view, Pissarro and his wife and kids give Cézanne and his unmarried girlfriend and their baby a sense of home. When you see the images of Pissarro by Cézanne, there is a humane quality that you don’t see in the reverse. It’s not a mirror.

Some reviewers–Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker and Jerry Saltz in the Village Voice—described the exhibition as a showdown between the good and the great, with Cézanne coming out on top. Do you think their reaction reflects a predisposition to more radical Modernism?

That’s exactly right. Predisposition is the word. It’s easier to find validation of your preconceptions than to question them. And in fact this show did question those. Not to say Pissarro is better—absolutely not, that would be completely ridiculous—but to say there’s another story there. And it’s not a Modernist story of who’s upping the other.

Conversely, Dana Gordon in Commentary argues that Pissarro invented abstraction and is the true father of Modernism, and has been unfairly eclipsed by Cézanne.

Again, it’s against the grain of the show to pull out one of them and say he’s the greater. At the end, he says one reason why people have been oblivious to Pissarro’s greatness or stature is because Judaism had some part in this.

Do you think he was marginalized because he was Jewish?

I don’t really think so. I don’t think people associated him with being Jewish. Even today, I hear people say, “I had no idea that Pissarro was Jewish.” Only in the 1970s and 1980s did art historians make heavy emphasis on Pissarro’s Jewish background, when it became cool to claim one’s own identity, one’s own difference.

Of course, some people knew. Barnett Newman’s widow, Annalee, used to invite me to tea regularly. Every time, she would have another Pissarro on the wall. I said, “What are you doing, squandering your assets buying Pissarro?” She said, “You didn’t know he was Barney’s favorite artist?” I never thought this major Abstract Expressionist would have an interest in Impressionism. She said, “It wasn’t Impressionism, it was Pissarro.” For Barney, he was an anarchist, an atheistic Jew who ran away from this but retained certain values. And those values that he found in Pissarro included abjection for anything sentimental. Which of course you find again in Cézanne. That’s a platform on which modern art is built.

There’s a great quote by Pissarro that Newman would have adored: “Beware of prettiness,” Pissarro says. “Prettiness is a danger much worse than ugliness.”

Robin Cembalest is executive editor of ARTnews. She blogs at letmypeopleshow.com. Her Twitter feed is @rcembalest.

Robin Cembalest is executive editor ofARTnews. She blogs at letmypeopleshow.com. Her Twitter feed is @rcembalest.