Against the 1970s

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo is a beautiful film and also a document of everything that’s rotten about the generation that came of age in the 1970s

Like people, works of art age, often ungracefully. The few and the fortunate remain appealing, while the rest fall into a sweet and slow decay. Among the latter, the most wretched are those objects of beauty that would have been rewarded with eternal life had they not had the misfortune of being affiliated with some dark reality. That is the case with Leni Riefenstahl’s gorgeous documentaries, which are today viewed solely as dried-up propaganda, or with the 1915 classic Birth of a Nation, in which cinematic mastery has been shadowed by its celebration of the Ku Klux Klan. El Topo belongs in this grim group as well: A stunning and imaginative film, it can now be seen largely as a testament to the failure of the generation that produced and revered it, the men and women who were born in the 1950s or early 1960s, who came of age in the 1970s, and who, with very few exceptions, have brought nothing but shit into this world.

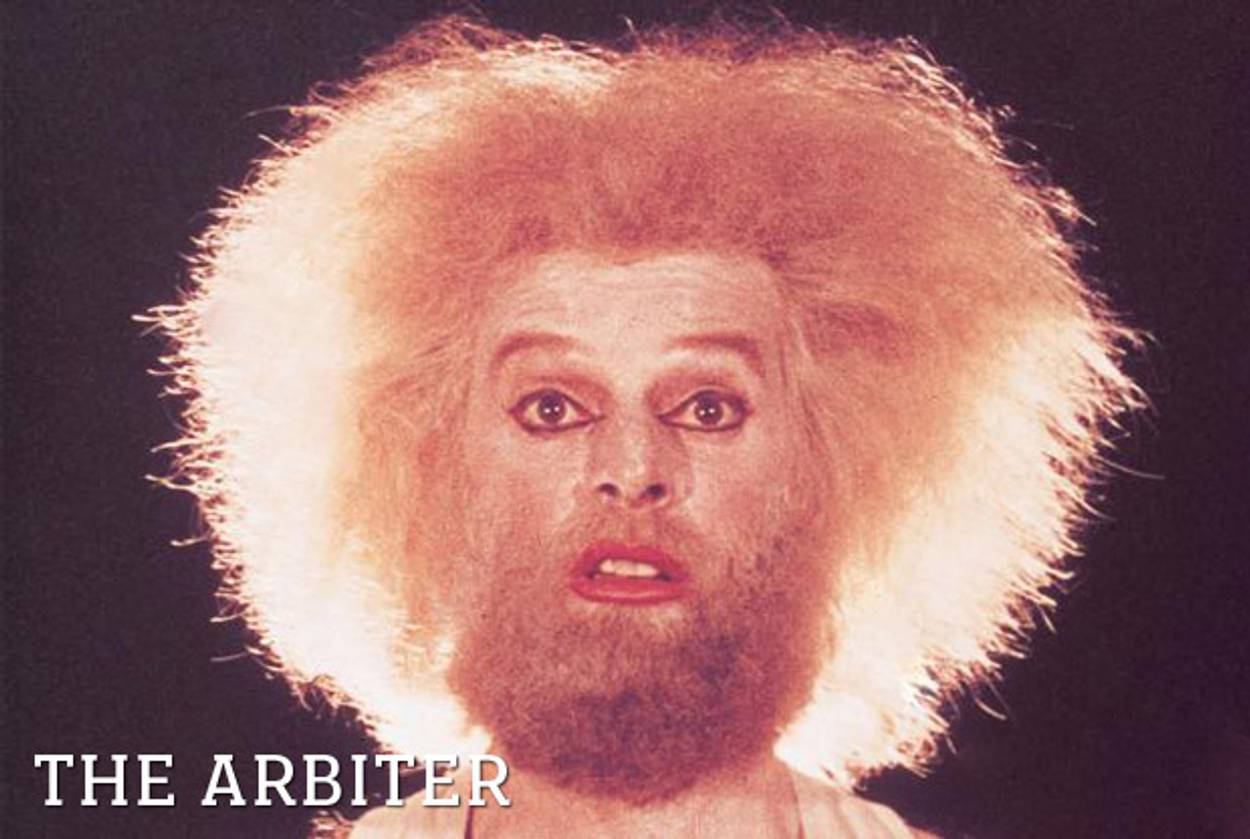

Few beyond a small circle of film loons are likely to have seen El Topo since its release in December 1970, so a brief recap of the plot is in order: El Topo (the Mole), a silent and hardened cowboy, roams the desert, defeats four gunslingers—each representing a particular Eastern or Western religion or philosophy—and then frees a tribe of grotesque creatures who revere him like a god. There’s also a man without arms carrying on his shoulders a man with no legs, a host of cantankerous dwarves, a smattering of naked children, and generous heaps of strange and beautiful images, mostly imitating religious iconography or featuring the heavily deformed.

What does it all mean? It’s hard, if not impossible, to tell. In nearly every one of its haunting scenes, El Topo violates one of Roger Ebert’s seminal principles of cinema: If you have to ask what something symbolizes, it doesn’t. And that’s a radical departure in film history: Whereas the film visionaries of the 1960s were sometimes accused of peppering their work with symbols whose meaning was all too obvious—Pauline Kael memorably made such an accusation of Fellini—their successors a decade later favored symbols that looked swell but represented nothing.

That’s an apt metaphor for the seminal differences between the Baby Boomers and the generation that followed: The former sought spiritual redemption in ways that were frequently only skin-deep, while the latter abandoned the search altogether for a series of titillating spectacles. The Boomers gave us the 1960s, which meant rock ‘n’ roll and the New Wave and the New Left and other movements that managed to deliver a few brief moments of true transcendence before dying down. The generation that followed, in turn, delivered disco and cocaine and Reaganomics, which all seemed like uplifting ideas for a short spell but eventually ended up causing severe damage to the nation’s body and soul. Try to find more than a handful of great authors, musicians, filmmakers, or leaders who emerged of that generation; I doubt if you can.

Anyone interested in understanding how a nation could have gone from Neil Young and Bonnie and Clyde and Naked Lunch to Neil Diamond and Dirty Harry and Fear of Flying in a decade should look at El Topo for clues. Portrayed by Alejandro Jodorowsky—who also directed, wrote the script, and composed the ethereal music—the Mole is the definitive creature of the 1970s: He’s a facsimile of a Xerox of a cowboy, a spiritual seeker who has gleaned most of his wisdom from overheard sound bytes, a two-bit hero who isn’t even half as tough as he thinks he is. When he meets the aforementioned gunslingers—guru types who have suffered for their insights—he defeats them all by cheating. He’s the George W. Bush of surrealist Westerns, all bravado, no skill, and a lot of luck.

Which means he’s also the perfect hero for his generation, and, unfortunately, for mine as well. In one crucial respect, we—those born sometime in the late 1970s, when El Topo was considered radical chic—are very much our stupid parents’ stupid children. Like Jodorowsky, we make and revere the sort of entertainment that is rich in symbolism but, ultimately, means nothing. Anyone spending a few hours with Adult Swim, for example, the popular adult animation strip on Cartoon Network, would see the mark of El Topo immediately: shows like Squidbillies, Superjail!, and Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job offer nonsensical images, impenetrable dialogue, and an aura that mixes mystery and mindlessness. On network television, the ever-popular Family Guy, with its never-ending non sequiturs, delivers a milder version of the same effect. Tumblr, the popular microblogging service, is a shrine to empty and bizarre visuals. In some important ways, we’ve come a long way since the days of El Topo: Whereas Jodorowsky liked his symbolism meandering and unfocused, we enjoy ours hyperkinetic and uber-referential. The desert, where the Mole roams, is a perfect metaphor for the 1970s generation’s aimlessness, whereas the rat-a-tat busyness of the Internet is tailor-made to ours. But the spirit is the same: We, the disaffected young of America, hail our media just as our parents once hailed Jodorowsky, convinced that there’s virtue in being unclear. There isn’t. Much of culture consists of mythology; when our symbols became senseless, when they are rapidly interchangeable, culture dies.

Jodorowsky, unsurprisingly, has a different take on things. To him, El Topo is the primary document of Neo-Outsiderism, a novel ideology of the period and a supremely silly one at that. Whereas the outsiders of the 1950s, with their white T-shirts and blue jeans, sought to build alternative families to replace the ones that had rejected them—consider James Dean, Natalie Wood, and Sal Mineo as Father, Mother, and Child in Rebel Without a Cause—the outsiders of the 1970s reveled in the terminal nature of their alienation. The Mole—I’m not spoiling much here, as El Topo has little by way of plot to begin with—ends the film by immolating himself. He has to die, alone and a hero; men of his generation know all about glorious deaths but nothing about the silent struggle of contented, productive lives.

In the Cannes Film Festival of 1988, Jodorowsky handed Ebert a typewritten autobiography. “Was born in Bolivia,” it read, “of Russian parents, lived in Chile, worked in Paris, was the partner of Marcel Marceau, founded the ‘Panic’ movement with Fernando Arrabal, directed 100 plays in Mexico, drew a comic strip, made ‘El Topo,’ and now lives in the United States—having not been accepted anywhere, because in Bolivia I was a Russian, in Chile I was a Jew, in Paris I was a Chilean, in Mexico I was French, and now, in America, I am a Mexican.”

Perhaps that is the case. More likely, however, Jodorowsky and his work weren’t accepted anywhere because, well, it’s designed not to be accepted anywhere. Rather than create a serious alternative to mainstream schlock—which would mean seriously engaging with serious subjects—he and too many others like him chose to give free roam to their inclinations, to indulge without end, to ignore the holy and humbling obligation artists should have to their audiences and engage instead in vapid stylistic self-gratification. It is not surprising that, having watched El Topo, Peter Gabriel rushed to write and compose The Lambs Lie Down on Broadway, a gratingly pretentious concept album by his band, Genesis. Marilyn Manson is also a fan. Enough said.

And yet, El Topo deserves more than a footnote in film history. Enamored with Jodorowsky’s work, John Lennon convinced his manager, Allen Klein, to finance the director’s next movie, The Holy Mountain. Giddily, Jodorowsky proceeded to push his own generous boundaries and allegedly locked his actors in a house for several months, depriving them of sleep and feeding them a diet of psychotropic drugs. The film, another hyperbolic spiritual quest for redemption, was a mess, but Jodorowsky, still admired, announced his intention to direct a very loose adaptation of Frank Herbert’s legendary science fiction masterpiece, Dune. A year later, having squandered enough cash and good faith to last most directors a lifetime, Jodorowsky was finally kicked off the project; it was handed instead to a relatively unknown filmmaker, David Lynch. Another novice, Ridley Scott, hired many of Jodorowsky’s now unemployed crew, including the writer Dan O’Bannon and the set designer HR Giger, to make his first big film, Alien. Both directors had the good sense of knowing that a film was more than rich and strange imagery; they applied structure and discipline, and they made history.

It is in this light that we have to watch El Topo. It is a very promising film that allowed its obsessions to take over, that expended all its energy on being hip, so focused on its own issues that it forgot it existed in a real world with real people who have real concerns. In other words, El Topo is just like its original fans, the men and women to whom we owe so much of the greed and squalor of the past three decades. With some luck and a lot of hard work, both will soon be no more than a historical artifact from a bygone era of self-centeredness.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.