The Classic Kiddush Trio

How schnapps, herring, and bowtie cookies became standard fare in shul—and why they’re making a comeback

When I was growing up in the 1980s and ’90s, the Saturday morning kiddush at my mainline Conservative synagogue in suburban Chicago was a delightfully elaborate affair: Manischewitz wine, gefilte fish, fruit platters, and plates of Hydrox chocolate sandwich cookies. Add a bar or bat mitzvah sponsor, and the selection swelled to include egg salad, bagels and cream cheese, and frosted pastel petit fours that got recycled the following week without ever growing stale.

It’s a far cry from the kiddush at my independent minyan in the liberal heart of Brownstone Brooklyn, which these days seems to bend any way the congregation wants it to: organic grape juice, hummus and pita chips, homemade cookies, artisanal cheese and olives, and bags of Veggie Booty for the gluten-free kids.

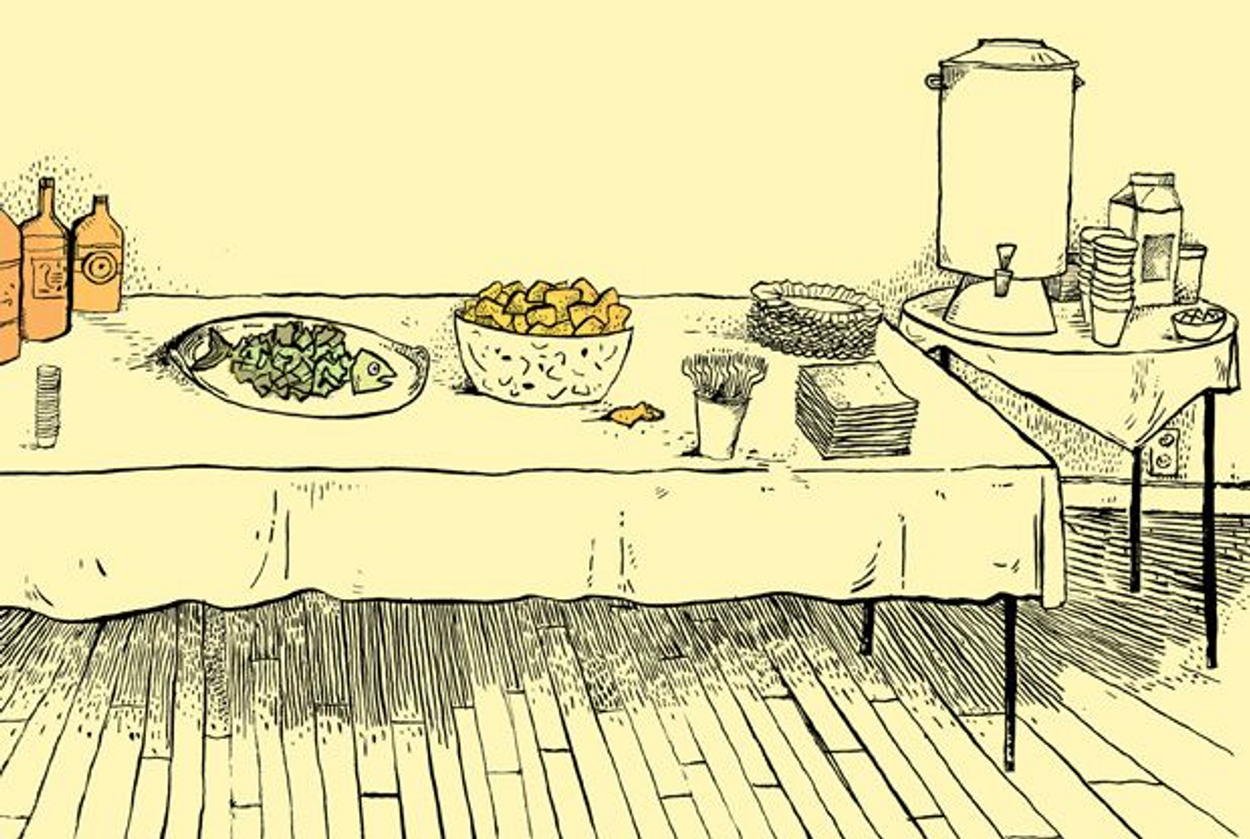

But a century ago, a kiddush in one traditional Ashkenazi synagogue more or less resembled any other, centering around three unchangeable foods: pickled herring, kichel (an egg cookie), and schnapps or whiskey. This humble and decidedly odd trifecta was, for years, synonymous with kiddush, the breakfast and social hour that follows Saturday-morning services. But while eating herring and crumbly, puffed cookies at kiddush might seem like a tradition older than Moses himself, it’s a surprisingly recent creation. “It’s actually an American invention,” said Gil Marks, author of The Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. It turns out, the kiddush my grandparents’ generation enjoyed eating (and tucking into their purses—“for later”) was a specific product of its time and place—an edible bridge between old world and new. And like many things from that generation that have since fallen out of style, the old-fashioned kiddush has recently begun to enjoy a modest resurgence.

***

The practice of making Kiddush (a prayer, literally meaning “sanctifying”) over wine as part of the Friday-night Sabbath meal likely dates back to 500 BCE. In third-century Babylonia, communities began reciting Kiddush in the synagogue so that travelers, who before the advent of hotels spent their entire Sabbath there, had an opportunity to hear the blessing. The Talmud explains: “Why must he [the Reader] recite Kiddush in the synagogue? In order to acquit travelers of their obligation, for they eat, drink, and sleep in the synagogue” (Pesachim 101a).

The Talmudic rabbis also instituted a Kiddush to be recited Saturday morning (right before lunch), though it never acquired the same ritual significance as Friday night. Because of this, Marks writes, Saturday’s Kiddush “may be recited over either wine or any drink considered chemer hamedinah (any meaningful national beverage),” while Friday night’s Kiddush must be said over the holiest of Jewish drinks: wine (or grape juice).

In early 20th-century America, Kiddush with a capital “K” (the blessing) gave rise to kiddush with a lowercase “k” (the social hour). Community leaders began to understand the importance of the synagogue as a place for congregants to rest and form relationships—especially for hardworking immigrants in a new and unfamiliar country. Meanwhile, Marks told me, “people were becoming more ignorant of certain traditions,” so synagogues responded by institutionalizing some rituals once designated for home. My father-in-law, Chaim Fruchter, remembers his rebbetzin mother “doing her best to make a nice sit-down kiddush to give congregants the Shabbat experience they would not have at home.”

From a gastro-sociological level, the development of kiddush makes perfect sense: Whenever Jews and socializing meet, a little nosh is likely to follow. But the specific nosh that emerged (herring, kichel, and schnapps) was no accident. “Early 20th-century synagogues rarely had kitchens, let alone iceboxes or refrigeration,” Marks said. So, foods that traveled well and kept for long periods of time, like pickled fish, were ideal.

Because Kiddush is supposed to be said in association with a meal, that nosh also had to be substantial. Hence the kichel, an egg cookie sprinkled with sugar that, like other cookies, cakes, and other nonbread grain foods, requires one to say a mizonot blessing, bumping up its status to a near-meal. In a move that might horrify some contemporary taste buds, kiddush-goers would top the kichel with a juicy bite of fish and eat them together as a sweet, briny sandwich. And then there was the schnapps. Brought over from Eastern Europe, where it was regarded as chemer hamedinah, schnapps and whiskey were considered suitable ritual substitutes for wine. Never mind the whole issue about drinking early in the day; these drinks tasted like home.

This kiddush trio lasted without much variation through the 1950s, at least in traditional Ashkenazi synagogues. Jonathan Sarna, a professor of Jewish history at Brandeis, told me that Reform temples provided an exception to the rule: There, they typically served “sweet wine and cake” in place of the old country foods, and preferred to call their kiddush gatherings by the less-ritualized term “collation.”

Starting in the 1950s, though, things began to change all over. As Jewish communities acculturated, spread out, and climbed the social ladder, the synagogue kiddush followed suit, becoming increasingly elaborate. Instead of just herring, one also started to find more expensive items like lox, sable, and whitefish. (By then, refrigeration was widespread.) “Synagogues displayed their affluence, and proved that they had made it in America, by hosting lavish kiddushes,” said Sarna. For individuals and families, sponsoring kiddush for a bar mitzvah, engagement, or other occasion became “an opportunity to display one’s success in a sanctioned environment,” said Jenna Weissman Joselit, a professor of history and Jewish studies at George Washington University.

People’s tastes changed, too. “By the time the baby boomers came around, chocolate chip cookies were common, even in kosher bakeries,” said Marks. “Compare that to kichel and you’re going for the chocolate chip!” Meanwhile, in his book The Gift of Rest, Sen. Joseph Lieberman notes that, over time, the cheap blended whiskeys of his youth have been upgraded to “a fine array of single-malt scotches which … have become to some as Jewish as bagels and lox.”

The kosher revolution of the late 20th century, during which a slew of food companies acquired a hekhsher for the first time, further affected the traditional kiddush. Marks cites the kosher certification of Entenmann’s in the early 1980s as a watershed moment in kiddush history. Before that time, synagogues relied on local kosher bakeries, if there were any, to provide cookies and other sweets. But with their kosher stamp of approval and broad distribution, Entenmann’s crumb cakes, pecan Danish rings, and marble loaf cakes quickly took over. “At my shul in Richmond, Va., the kiddush ladies would buy a bunch of Entenmann’s on sale and stick them in the freezer,” he said.

Over the last few decades, the Saturday-morning kiddush has continued to broaden and evolve along with the American Jewish community. It often features classics like egg salad, pickles, lox, and more recently hummus. But the real beauty of the “modern” kiddush lies in its potential for variety. The little tweaks and personal additions—which tend to get discouraged in other parts of organized Jewish life—make all the difference and serve as a window into a congregation’s personality. My upscale-hippie congregation’s Veggie Booty and Camembert cheese, for example, might be matched by a Reform temple’s mini muffins and Israeli salad, or an Orthodox congregation’s cholent and potato kugel. Some congregations also host “kiddush clubs,” semi-clandestine gatherings held during standard kiddush time (or sometimes during the service itself, usually to the rabbi’s annoyance) where people, typically men, schmooze over that single-malt scotch Lieberman wrote about.

And thanks to today’s wave of hipster-fueled interest in previous generations’ food and customs, herring is making a comeback among younger communities as well. A 2011 New York Times article attested to the briny fish’s comeback among the artisanal food crowd. Meanwhile, at a recent kiddush at my minyan, I couldn’t help but notice the gusto with which my fellow Brooklynites attacked the herring—and more interestingly, discussed the fact that they were eating herring and liking it.

Kichel has not fared as well, an unfortunate casualty of changing tastes and expanding alternatives. Though maybe it’s only a matter of time before its potential is rediscovered. (Perhaps the recipe included here will help.)

No matter what’s on the menu, kiddush serves the same essential function today that it did a hundred years ago: to be a moment of social connection. As my mother, a longtime kiddush organizer, told me: “A bunch of us parents would drop you kids off at Hebrew school and then head into the synagogue’s kitchen and start pouring grape juice and slicing cake. We would laugh and share stories—most weeks, it was the best thing about going to shul.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Leah Koenig is the author of The Jewish Cookbook,Modern Jewish Cooking: Recipes & Customs for Today’s Kitchen, and The Little Book of Jewish Appetizers.

Egg Kichel (Bowtie Cookies), reprinted with permission from Inside the Jewish Bakery: Recipes and Memories From the Golden Age of Jewish Baking, by Stanley Ginsberg and Norman Berg

3 Tbsp. granulated sugar

1 tsp. table salt

4 large eggs plus 9 large egg yolks

3/4 cup vegetable oil

1 1/4 tsp. vanilla extract

1 1/4 tsp. rum flavoring (optional)

3 1/2 cups unsifted all-purpose flour, plus more for dusting

3 cups granulated sugar, for coating

1. Combine all the ingredients through the flour in the bowl of a standing mixer, and mix with the flat paddle beater set at low speed until dough is smooth and has a well-developed gluten, about 20 minutes.

2. Turn the dough out onto a well-floured work surface and knead for 2–3 minutes, until it no longer sticks. Cover it with plastic wrap or a damp cloth, and let it rest for 20–30 minutes to relax the gluten.

3. Preheat your oven to 350 degrees, and line two baking sheets with parchment paper.

4. Spread 1 1/2 cups of sugar evenly over your work surface, and roll out the dough to about 1/4-inch thick. Sprinkle the remaining 1 1/2 cups sugar over the top surface of the dough. Using a sharp knife or a pizza wheel, cut the dough into 1-inch by 2-inch rectangles. Give each strip a half twist to form the bowtie, and arrange on cookie sheets, about 1-inch apart.

5. Bake for 20–25 minutes, until the bowties are golden brown. It’s important that the cookies be fully baked, otherwise they’ll collapse as they cool. Remove to a rack, and let cool for 3–4 hours, until cold and thoroughly dried out. Store immediately in a Tupperware to retain freshness.