A Great Thinker Rediscovers His Judaism on the Day of Atonement

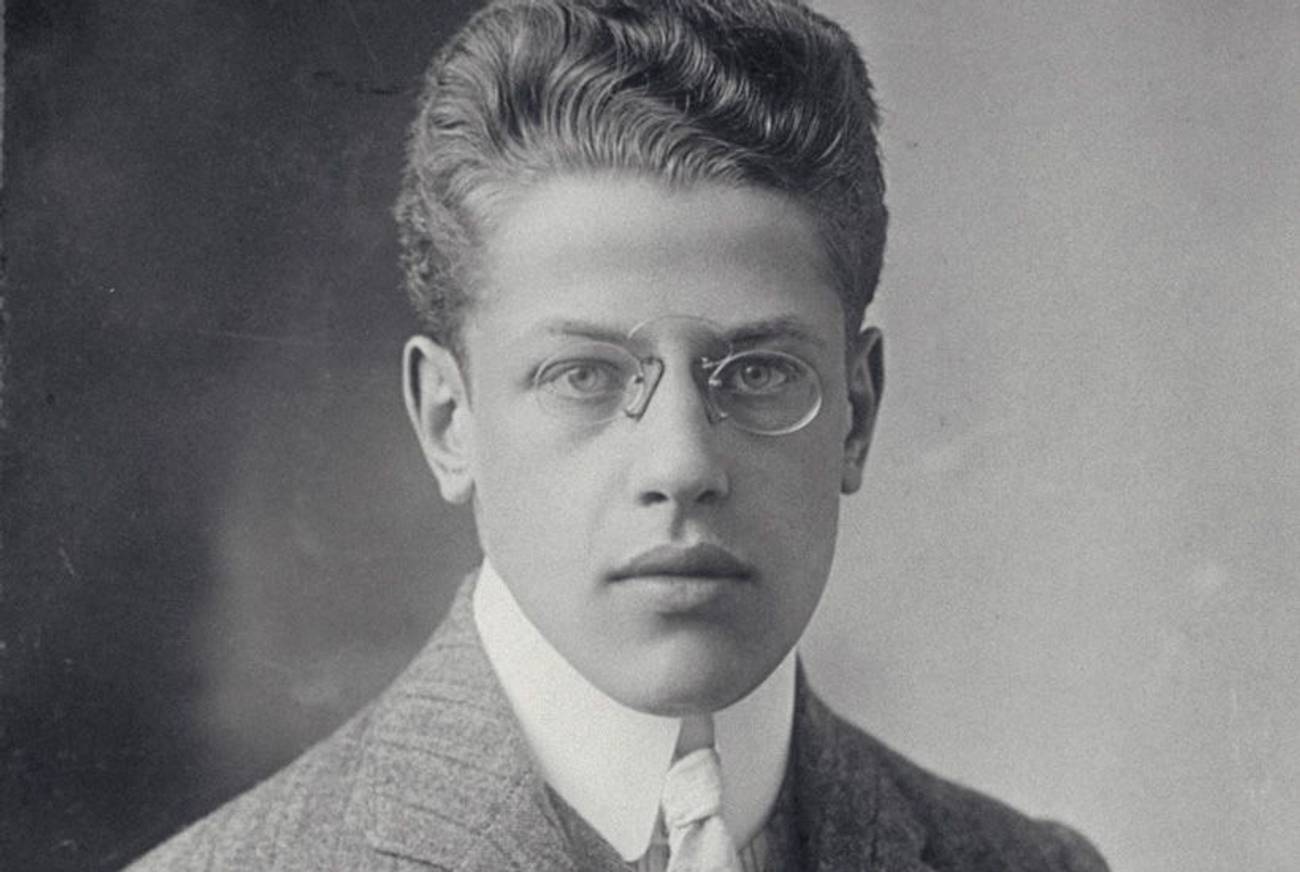

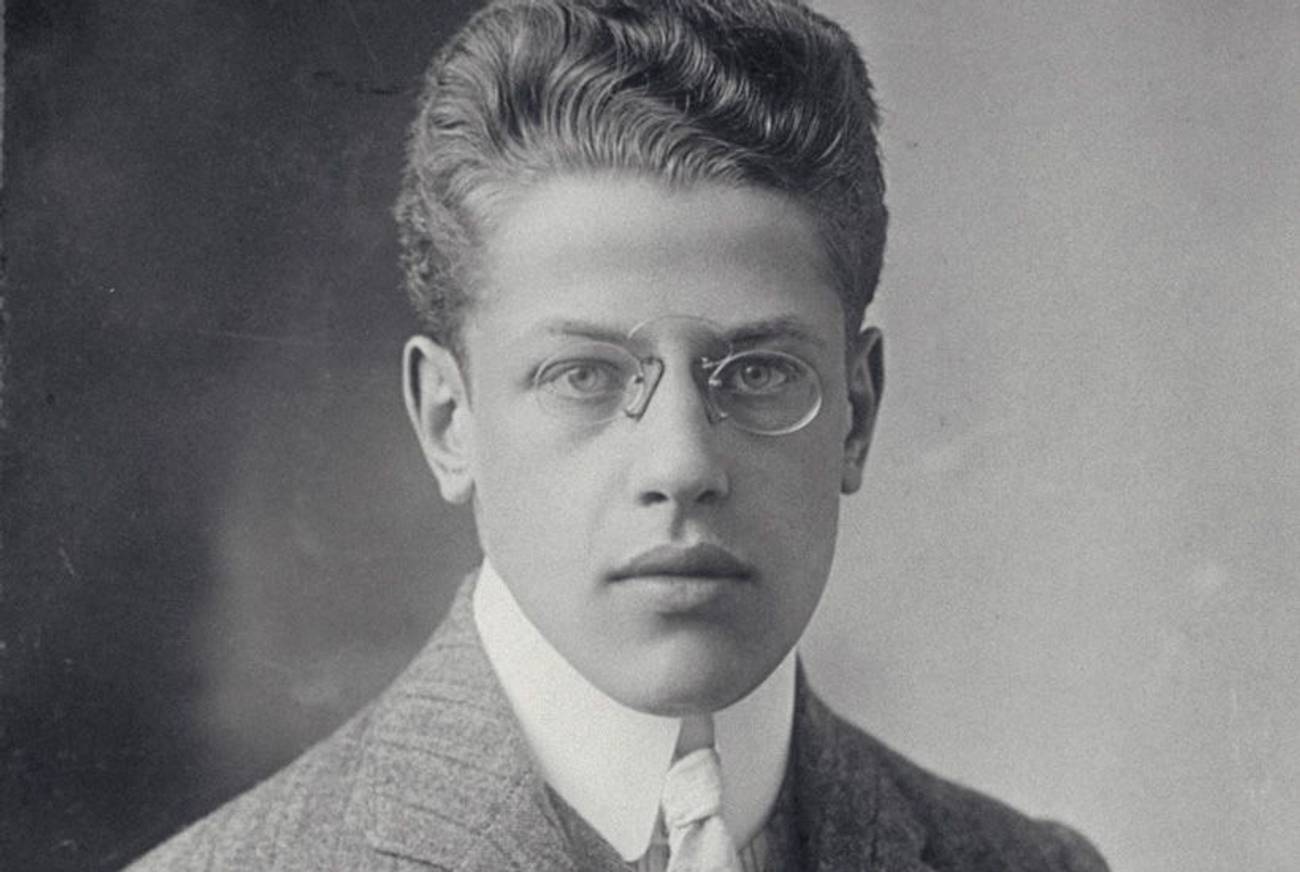

Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig was set to convert to Christianity a century ago. Yom Kippur services changed his mind.

In October 1913, 100 years ago these High Holidays, 26-year-old philosopher (and Jew) Franz Rosenzweig was preparing for a crucial conversion ceremony: his own, to Christianity.

However, because he insisted on converting “as a Jew, not as a ‘pagan,’ ” Rosenzweig dutifully attended services on the Day of Atonement 1913 at a small Orthodox synagogue in Berlin. In his mind, participation in the Day of Atonement was a necessary, preparatory step toward his Christian baptism. “Here was a Jew,” writes Nahum N. Glatzer in his biography of Rosenzweig, “who did not wish to ‘break off,’ but who deliberately aimed to ‘go through’ Judaism to Christianity.”

What happened to him thereafter constitutes a paradox difficult to grasp: How is it possible that Rosenzweig’s reconnection with his native Judaism could occur only when he stood upon the virtual threshold of a Christian altar? And what role did his participation in the Yom Kippur service for 1913 play in his ultimate decision not to convert to Christianity?

Rosenzweig’s life after that determinate day, writes Glatzer, is nothing less than “the story of a rediscovery of Judaism.” Rosenzweig’s subsequent writings—most notably “Atheistic Theology” (1914), the magisterial Star of Redemption (1919), Understanding the Sick and the Healthy (1921), and “The New Thinking” (1925)—serve to short-list him among a handful of the greatest of Jewish thinkers since Rashi, Yehuda Halevi (whose Hebrew poetry Rosenzweig translated into German), and Maimonides.

To some, this inclusion of a 20th-century writer on a short-list of the all-time greatest Jewish philosophers must appear almost heretical. Paradoxically, however, reading Rosenzweig’s reasoning after his (non-)conversion experience during the Days of Awe in 1913, especially in light of the rest of his too-short life, brings traditional Jewish philosophy into sharper focus today: Which ideas, if any, in the modern philosopher’s subsequent writings fulfill traditional Judaism’s promise to the modern world?

When one reads Rosenzweig’s oeuvre, it becomes clear that his prime concern is idolatry. His approach focuses not on “graven images” themselves, however, nor their prohibition: It has to do with how human beings misapply the second commandment, in practice more than in mere theory. Maimonides, to cite just one of Rosenzweig’s precursors, considered the second commandment, properly understood, to be the soul of Judaism. Contemporary scholar Leora Batnitzky writes in Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered: “It is no accident that Maimonides begins his great philosophical work The Guide for the Perplexed with a discussion of anthropomorphism”—i.e., the projection of human traits onto God, an animal, or an inanimate object—as the error behind idolatry. Rosenzweig would take issue with Maimonides over the word “anthropomorphism,” but such refinements are to be expected: Disagreement is the motor of the Midrash.

Rosenzweig never explicitly recounted exactly what happened to him during and immediately after Yom Kippur 1913. It’s likely that he never explained in detail the rationale behind his decision not to convert for fear of offending Christian friends. But in light of his subsequent writings, we can surmise that the second commandment’s injunction against idolatry must have played a role in his Yom Kippur epiphany. In fact, the second commandment, viewed through Rosenzweig’s post-1913 thought, might also serve to assuage “perplexities” for Jews today.

As a product of a German university in the first years of the 20th century, Rosenzweig (born Dec. 25, 1886) came of age within a rationalist Weltanschauung imbued with faith in history and belief in progress. His thesis, titled Hegel und der Staat (Hegel and the State), explored the phenomenological idealism prevalent then in German academic philosophy.

But Hegel’s view of history, as inexorable patterns of phenomena to be contemplated from the lofty heights of philosophy, no longer satisfied Rosenzweig. “For Hegel and his ‘school,’ history was divine theodicy,” wrote Alexander Altmann, paraphrasing Rosenzweig in a 1944 essay. “[But] for us religion is the only true theodicy.”

As early as 1910 such a “true theodicy”—that is, a valid explanation to man concerning the ways of G-d—presented a life-altering challenge to Rosenzweig’s youthful Hegelianism. At the same time, the prospect of embracing Christianity began to supplant his neglected, agnostic Judaism. Rosenzweig felt that this spiritual “battle” was a matter of life and death; the crisis would culminate between July and October 1913. His contentious friendship with Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, a fellow student of Jewish upbringing who had converted to a profoundly “conscious” Christianity, is documented in a series of letters published under the startling title Judaism Despite Christianity.

“[Rosenzweig] was the son of an old Jewish family that had lost most of its Jewish heritage,” wrote Altmann, à propos of the exchange of letters between the two young men, in his essay “About the Correspondence” in Judaism Despite Christianity. “True, there was a certain loyalty to the old faith and community, both on his and on his parents’ part. But it was of no vital importance to him. And, rather than pretend to be a Jew, he tried to ignore the fact, seeing that, assimilated as he was to German cultural life, his mind had already become Christianized.”

For his part, Rosenzweig would come to believe that Rosenstock was correct in his revelatory faith—thus, Rosenzweig’s earnest need to become a Christian as a means of accounting for revelation. The uniquely “revealed” answer to the post-Enlightenment disenchantment confronting the modern world, for Rosenstock, was the one embodied by Jesus of Nazareth and retold in the Gospels. Braced as he was in an armor of such profound certainty, “Rosenstock regarded his friend’s [Rosenzweig’s] superficial Judaism as merely ‘a personal idiosyncrasy, or at best a pious romantic relic’ that could not address itself” to modernity, wrote Glatzer.

The two friends engaged in heated, “to the death” arguments about theology. During one such discussion, Rosenzweig asked his Christian friend what he would do if all the answers founded on his faith were utterly to fail. “I would go to the next church, kneel, and try to pray,” Rosenstock replied. Again, paradox plays the crucial role in this dialogue: Rosenzweig’s friend’s sincere, fully conscious statement of Christian faith would plant a seed in Rosenzweig’s Jewish heart that would lead to the latter’s decision not to convert to Christianity.

In effect, Rosenzweig experienced a paradoxically non-mystical enlightenment on Yom Kippur 1913: a “meta-historical” breakthrough, yet at the same time one solidly anchored in time; a theoretical, yet thoroughly pragmatic epiphany; a revelation irreconcilable with Christian religion, yet committed anew to Hashem via the Neilah service, the final prayers spoken on the Day of Atonement. Just as it is not possible to “unring” a bell, Rosenzweig clearly could not “un-sound” the shofar he heard in 1913.

“Had it not been an experience of his own life,” Glatzer writes, “all of this [i.e., Rosenzweig’s subsequent works and writings] could not have been accomplished. This is the voice of a man [born and raised a Jew] who broke with his personal history, and—in an act of conversion—had to become a Jew.”

So, a Jew walks into shul on Yom Kippur and . . . converts to Judaism! A truly circular paradox like this represents a logical extreme of mere, mundane ambiguity; indeed, the inherent ambiguities generated by the taboo against “graven images” (including the signifiers of language) are directly responsible for a perennially long shadow cast upon the history of Western philosophy.

Christian revelation, in this play of shadow and light, cannot be represented properly by the image or statue of a crucified body without risk of confusion. If a given crucifix, painting, or statue is in fact believed to represent the Son of God, how can it not trigger an “anti-idolatrous” reaction in a Jew

But this is not the whole story for Franz Rosenzweig. Batnitzky shows how he treats the crux of idolatry not as deriving from how we humans think about G-d, via image, object or fetish; instead, the problem derives from how humans improperly worship G-d, in our actions: “The rabbinic term for idolatry—avodah zarah—is ambiguous. It means alien worship, but what is alien, the object of worship or the type of worship?”

In the context of modern philosophy, then, the problem of idolatry for Rosenzweig becomes hermeneutical (from Hermes, Greek god of messengers, crossroads, thieves, and boxers): focused on the message-spark that jumps the gap, not on the objects determining the width of the gap itself. “Rosenzweig’s emphasis on idolatry as improper worship means that images are not intrinsically idolatrous,” writes Batnitzky. “The second commandment’s ban on graven images is not an all-out ban on visual representation. Rosenzweig argues that images are both potentially redemptive and idolatrous.”

Hence, another paradox: “The possibility of idolatry for Rosenzweig cannot be dismissed merely by thinking about God properly,” writes Batnitzsky. “Rather, idolatry is always a possibility, especially for those who know the true God. Adherence to the ban on idolatry, then, means that one must always risk idolatry.”

The many such paradoxes underlying Rosenzweig’s post-Yom Kippur 1913 writing led the professor in him to reject academe, the theologian in him to reject theology, the philosopher to reject philosophy, even the writer to reject writing in favor of speech, as the “living word” through which he might embody the personal and communal renewal necessary for a Jewish community to thrive. In a letter written in 1920 to his teacher Friedrich Meinecke, he played down the importance of his masterpiece The Star of Redemption as mere “armor which protected him until he learned to get along without it.”

Rosenzweig wrote most of The Star of Redemption on postcards that he mailed to his parents from his artillery observation post near the front during WWI. For the final eight years of his life (he died at age 43), he suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, known in the United States as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Having “sworn off” philosophy, he also established the Freies Jüdisches Lehrhaus in Frankfurt as a means to convey to young people an unmediated, or at least minimally dogmatic, relation with G-d: In the hermeneutic process of studying images and languages, he taught, one is able to become Jewish without need for “idols” or “eternal truth.” This did not exclude artworks and texts; in fact, personal and even heterodoxical interpretation of artworks was the skill most emphasized in the Lehrhaus.

As the disease worsened, his gradual loss of speech and motor skills led him back to writing, for which he used a specially designed typewriter upon which he could type while holding a pointer-rod in his mouth. Friends and family who knew him during this illness unanimously celebrate his strength, faith, and ability to bear such an affliction—and painstaking mode of communication—with never a complaint.

It seems fitting that one of the Torah portions (Deuteronomy 11:26-16:17) pertaining to Elul—the Hebrew month of preparation prior to the beginning of Rosh Hashanah—is called Re’eh (“See!”). It begins with a clear choice: “See, this day I set before you a blessing and a curse: blessing, if you obey the commandments of the Lord your God that I enjoin upon you this day; and curse, if you do not obey . . . but turn away from the path . . . and follow other gods, whom you have not experienced.”

This portion may well have served as inspiration for Rosenzweig’s epiphany as he approached and avoided the altar of Christian faith on Yom Kippur 1913. The Re’eh stresses the difficulty of the path, the demanding and often perplexing practice and enactment of wisdom and faith, even as it proposes a curse upon prospective idolaters. It enjoins not a theory, but a corporeal realization of halakhah, the system through which any Jew acts to bring God into the world. Thereby, the Torah accentuates each individual’s embodiment or incarnation as the shape available to a living, renewed Jewish life; it forms a metaphorical, invisible yet indestructible bridge connecting the antique sources of Jewish wisdom with a most vibrant philosopher of the persistence of immediacy, even unto the epochal paradoxes of modernity and the postmodern condition.

Brian Eno, best known as a musician and creator of ambient, aural space, has said something to the effect that everything is an experiment until one has a deadline; only then comes action, productivity, connection, and community. For Franz Rosenzweig, as for all Jews, there is no better deadline than Yom Kippur.

James Winchell recently retired from teaching at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash.